Читать книгу The Last Queen of the Gypsies - William Cobb - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Piper, Florida

July 1964

The man Lester Ray found to work on the car was named Lyman Duck. He found him in Saddler’s Lounge. Lyman Duck was a little, extremely slim man with thin black hair cut vaguely—as near as he could manage, probably—in an Elvis cut, with long sideburns and greasy ducktails in back. He had showed up at Saddler’s Lounge a couple of years ago, and he always sat at the same table and nursed a six-pack of Falstaff (Saddler’s was a package store as well as a bar, and beer was slightly cheaper by the six-pack on the package store side, so Lyman Duck would buy his over there and bring it in, which Gerald Saddler allowed, since it was his beer sold either way, and if somebody wanted to drink their last four beers lukewarm it was all right with him). Lyman Duck always brought along his ugly daughter, a diminutive, dwarf-like girl not much more than three feet tall, in a faded red dress, which she must have washed out at night—when, if ever, she washed it out and hung it up to dry—because she always had it on. She was buck-toothed, with hair the color of a boiled carrot, cut ragged and shoulder-length like somebody had chopped it off with a hatchet. She sat at the table with him, drinking Dr Pepper and gnawing on a plate of pickled pig’s feet. Nobody ever sat down with them, because they stank, and nobody knew where they lived. Gerald Saddler, the owner and bartender, a big man with a bullet head and thick neck and elephantine shoulders, said—laughing—that he bet they lived in a culvert under the railroad tracks outside town. One that raw sewage leaked through.

Lyman Duck claimed to be a mechanic who could fix anything. He was always bragging about it. He claimed to have worked on Patton’s tanks in France back during the war, but nobody much believed him. He was a blowhard, and he might be a challenge to keep quiet, but he seemed to be Lester’s and Mrs. McCrory’s only choice, short of pushing the car into one of the local garages, who would probably get all suspicious and notify Orville McCrory that Lester Ray was stealing his mother’s car. Lester Ray knew virtually nothing about cars, just enough to worry that the old car would need parts that might not still be available, but Lyman Duck had winked at that and told Lester Ray not to fret, that he knew where to find any part he needed. Lester Ray offered him fifty dollars to get the car up and running, and keep it a secret, and Lyman’s daughter chimed in and said, “Seventy-five!” Lester Ray agreed.

The two of them showed up at Mrs. McCrory’s garage the next morning, Lyman toting a rusty tool box. “What’d you bring her for?” Lester Ray asked him.

“She’s my helper,” Duck said.

“What of it?” the girl said, glaring at Lester Ray. Her eyes were such a pale green they almost disappeared, and her nose was flat, as though it had been broken some time in the past.

“Nothin,” Lester Ray said. “I was just askin.”

“Curiosity killed the fuckin cat,” she said. She spat on the ground and wiped her mouth with the back of her hand.

“Yeah, well,” Lester Ray said, “y’all better get started, then.”

Lyman Duck raised the hood and peered inside. “Yes, sir,” he muttered. “Where’s the key at?” Lester Ray handed it to him. It was on a chain with an old yellowed rabbit’s foot. “I ain’t superstitious,” Lyman said, wiggling the rabbit’s foot in the air, “but we are gonna need some luck.” He tinkered around under the hood, tapping at the engine with a wrench. “You tried to start this sucker?” he asked.

“Yeah, it won’t turn over.”

“Battery’s dead as a doornail,” Duck said, “sucker’s three days older than God. We gonna need a new one. And some new spark plugs. And ain’t no tellin what all else.”

“No problem,” Lester Ray said. “Whatever you need.”

“Where you gettin all this cash, if you don’t mind if I ask.”

“I do mind,” Lester Ray said. “Now shut the hell up and get to work. And remember, this gets out, I’ll beat the shit outta both of you!”

They worked on the car for three days. When they needed a part or something, Lester Ray would go to the auto parts store out on the highway and buy it. When they didn’t stock it any more—the parts manager turned the rusted generator over and over in his hands; “Where in the hell did you get this damn antique thang,” he asked—then Lyman would send his daughter somewhere to fetch it; she might be gone two or three hours, but she’d come back with whatever they needed.

“Where you gettin this stuff?” Lester Ray asked.

“That’s for us to know and you to find out, buddy,” the girl said.

“Stealin it, I reckon,” Lester Ray said.

The girl glared.

“Well,” Lester Ray said, “they better be good parts, cause I’m gettin my money back if it don’t run.”

“It will,” Lyman Duck said.

Lester Ray stayed in the garage with them, to see that they kept working and to make sure they didn’t make off with anything. The girl mostly watched. The two of them sat on a couple of stacks of old National Geographics that had belonged to Mrs. McCrory’s husband. Lyman was on his back under the car, banging away on something. Then it was quiet again.

“What’s your name, anyway?” Lester Ray asked the girl.

“What’s it to you, son?” she asked, cutting her eyes at him. She was flirting with him. He hadn’t thought she was the flirting kind. For the first time he noticed she had pretty big breasts. It looked strange seeing breasts on a girl no bigger than an eight- or nine-year-old. If you could just get by her face she might be all right.

“I was just wonderin,” he said.

“My name is Virgin Mary Duck,” she said.

“You’re shittin me,” he said.

“No, I ain’t. My mama was a religious Catholic nutcase. She named me that, and don’t say anything about it or laugh at it because I like it.”

“Okay, I won’t,” he said. “Virgin Mary Duck,” he repeated. “Is that what they call you? The whole thing?”

“Don’t nobody ever call me anything, cept sweet Daddy under there, and he calls me V. M.”

“All right,” he said, “V. M. How old are you?”

“Old enough to know better,” she said. She cut her blanched-looking eyes at him again. “I’m fifteen,” she said, “sweet fifteen.” She smiled at him. About a quarter-inch of pink gum showed when she smiled.

They sat there for a while, listening to the metallic sound of Lyman tinkering underneath the car. Then Lester Ray asked, “Where do y’all live? You and your sweet daddy, as you call him.”

“In a tent, out in the Flatwoods,” she said.

“A tent?”

“Hell yes. Ain’t you ever heard of a tent before?”

“Yeah, I’ve heard of a tent,” he said.

“Well, what of it?”

“Nothin. You can live wherever the hell you want to live,” he said. “I was just wonderin.”

“Why?” she said, batting her eyes at him, “you think you might want to come see me sometime?”

Not likely, he thought. For one thing, the garage was close and hot, and he could smell her strong. For another, she was about the ugliest girl he’d ever seen.

“I might have some beer for you,” she said, “and somethin else, too, if you know what I mean.”

Maybe you could put a paper sack over your head, he thought, but then how would he get by the stink of her? He was amazed that such a little body could smell that rank. “I ain’t got time to go visitin,” he said.

“Where you and that ol lady goin in this thing, when Daddy gets it fixed?” she asked.

“Well,” he said, “she just wants me to drive her around, you know, of a Sunday afternoon.”

“Shit,” she said. “You ain’t got no driving license. You ain’t old enough.”

“How the hell do you know how old I am?” he said.

“Cause I’m older’n you. You ain’t even old as I am.”

“How old I am ain’t got a thing to do with anything,” he said, “so shut up about it.”

“I bet I could teach you a thing or two,” she said. She winked at him.

He laughed. “I doubt it,” he said.

Lyman Duck came out from under the car and got in under the steering wheel. The hood was still up, like the car had its mouth wide open. He pressed the starter button with his thumb. The motor sounded at first like somebody rubbing two sheets of sandpaper together, then it sputtered. The car shook. The motor roared into life. Lester Ray felt lifted into the air, liberated. He could hardly believe what this would finally mean. He stood up and jabbed his fist into the air. Virgin Mary Duck jumped up, too, and started dancing around. She tried to hug Lester Ray, but he pushed her away. “Quit it,” he said. “Git away from me.” He went around to the driver’s side. It was difficult for Lester Ray to believe the car was actually running. He realized he had doubted all along that Lyman would ever fix it, and now he was as surprised as he was thrilled.

“You ever drove a car before?” Lyman shouted over the rumbling of the engine.

“No,” Lester Ray said.

“Well, look here now. This here is the accelerator pedal, see? You give her the gas with this. This here is the choke. You got to choke her some at first, to get the juices flowin. Same as you got to do to a woman, you know?” He laughed, and Lester Ray recoiled from his yellowed, rotting teeth. “You press this here button. This is the starter, and give it some gas at the same time. Once she gets to idlin good, you can let off on the choke. Oh, and you got to have the clutch down while you doin all that, I forgot to tell you.” He leaned down. There were three pedals, and Lyman had the left one pressed to the floor. “The other pedal is the brake. You use that to stop, all right? And this here is the gear shift.” He jammed it around here and there, “reverse, low, second gear, third. Got to have the clutch down when you doin that, too. Got it?” He shoved it into reverse. “Slam that hood down and get out the way,” he said. Lester Ray went around and closed the hood.

“Look out, now,” Lyman shouted. The car jerked and bucked, then slowly began to back out of the garage. Lyman backed out into the street and drove off down to the end of the block, the car backfiring a couple of times like cherry bombs going off, and turned right.

“Where’s he goin?” Lester Ray asked.

“Around the block,” V. M. said. “He’ll be back, don’t worry.”

Lester Ray stood with a stupid grin on his face, shaking his head back and forth. “Well, I’ll be fucked,” he said.

“I will if you want me to,” V. M. said.

“We can go anytime you’re ready,” Lester Ray said to Mrs. McCrory.

“Go where?” she asked.

“We got that old car fixed,” he said. “We can hit the road.”

“What old car?”

She was looking at him as though she didn’t know who he was, much less remember anything about their plans. “We got to get that alligator out of the house,” she said, “the one that was in the front hall this morning.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, “I’ll take care of it.” He was not alarmed. He knew she snapped back and forth, in and out. It was Orville he was worried about; they had two weeks left, according to what he had told his mother, but there was nothing fixed about it, nothing guaranteed. He might show up anytime ready to cart her off to the old folks’ home. As far as Lester Ray was concerned, he was not going to let that happen to her.

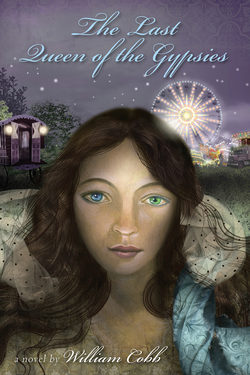

He had a plan, but they needed a running start. The West Florida State Fair was going on in Pensacola, and there would be a carnival with rides there, and Lester Ray knew that Gypsies usually traveled with carnivals, even ran them, he’d seen that himself with the smaller carnivals that came to Piper, and he planned to get a job with them and travel with them, wherever they were going, travel with them for the rest of his life if he had to, until he eventually met up with his mother. Who knew? His mother might even be traveling with that carnival. He knew that Mrs. McCrory didn’t care, as long as he kept her away from Orville and out of the nursing home. He had spent a little over two hundred and fifty dollars on the car out of the box in the pantry (the car had a 1944 Florida tag on it, and they were going to be conspicuous enough without being stopped for an expired tag; he’d had to give Lyman Duck ten dollars extra for a new tag, and V. M. had come back with a current 1964 Rhode Island tag, wherever it came from Lester Ray did not know or care and well knew better than to inquire) and that left them enough—roughly forty seven hundred dollars—for a good long while of wandering, even a longer while if he got a good-paying job with the carnival. He was not afraid of hard work, and he was as big and strong as most men; he could pass himself off as a lot older than he was without too much trouble.

“Your wife,” Mrs. McCrory said, “broke into the house and stole my panties.”

“Mrs. Mack,” he said, “I ain’t got a wife. And once we get on the road, you can buy all the underwear you need.”

“But I want my panties!”

“All right. I’ll tell her to bring them back, okay?” He knew she’d find her underwear in a drawer in her room.

“Lester Ray!” she exclaimed suddenly, “what are you doing here?”

“I came to let you know we got the car fixed. We can leave any time you want. I just got to go home and get some clothes and stuff.” He was praying that his father would not be there to make a scene. Not that his father cared where he went, or even that he was leaving, but he would not want him to go, because it was Lester Ray leaving and not him. Lester Ray might even have skipped the clothes, but he had to retrieve the picture of his mother from where he’d hidden it. He would never leave without that.

“Can you pack your suitcase?” Lester Ray asked.

“Of course I can, young man, I’m not a moron,” she said.

On the way down the sandy street to his house Lester Ray met Baby John on his mule, and the sight gave him a surprising stab of sadness. He would not miss much in Piper, but he realized with a jolt that he would miss Baby John, and he would not have thought he would since he rarely thought of him when he didn’t see him. Baby John had been riding his mule up and down Commissioners Street ever since Lester Ray could remember. That’s all he did all day, ride the mule up and down the street with no apparent purpose other than to do it. He was forty years old, and he lived with his elderly parents in a little white house up the road from Lester Ray, the third one, if you were counting, from the city dump.

“Evenin, Baby John,” Lester Ray said. Baby John was barefoot and wore faded, patched overalls without a shirt. There was no saddle on the mule, not even a blanket, and the bridle was cotton rope.

“Evenin,” Baby John said. “I’m gonna sang in church.” He held his index finger in the air and waved it around as though he were keeping time to music that only he could hear. He would always say that same thing if anyone spoke to him. He rode his mule to all the little country churches around Piper, whichever ones were having dinner on the ground that day, and he would get up during the service and sing. Nobody could understand what he was singing, could not tell if it were a religious song or not, maybe something popular he’d heard on the radio. Lester Ray had wondered if maybe what he was singing was something nasty or blasphemous, but he guessed that as long as the people couldn’t understand it they didn’t care.

It’s strange how you can sometimes tell if someone is home—is in the house—just by looking at it from the outside. Not chimney smoke or a car in front or lights on: it just looks different, like the presence of a live, warm body inside causes the outside appearance to subtly change, to undergo some chemical alteration. When Lester Ray looked at their house he knew his father was at home for the first time in over three weeks. He knew without a doubt that when he opened the door and went inside he would find his father either on the settee in the living room, at the kitchen table, or sprawled across his fetid bed, knew it so veraciously that it would have been cheating to have bet somebody money on it.

Earl Holsomback was at the kitchen table, a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon in his hand. There was a woman with him. She was at least as old as Earl was but she had on a kittenish, frilly pink dress, with ruffles all over it, like some little girl would wear. She had smeared her lipstick all around her mouth, outside her lips; Lester Ray supposed it was to make her lips look larger and more inviting, but she had failed miserably in the effort. His father was wearing a green mechanic’s coverall jumpsuit with ROGER stitched over the front top pocket in orange thread.

“Hey, boy,” his father said, “pull up a chair.”

“I ain’t got time,” Lester Ray said.

“Hoo-de-do, what you got to do thass so important you can’t set down here and meet Sherry.”

“I got somewhere to be,” Lester Ray said. He went over to a small chifferobe, missing one leg and propped on a brick, and began to stuff his few clothes into a pillowcase.

“What you doin, boy?” his father asked.

“Mrs. McCrory’s gonna wash my clothes for me. She’s got an automatic washer.”

His father turned to the woman and said, chuckling, “This here Mrs. McCrory’s his girl friend.”

“Hmmm, I’d be his girl friend anytime,” she said.

“He ain’t but fourteen years old, he’s just a boy,” Earl said. “Shut that shit up!”

“Uh-huh, I know he’s a boy! Hey, sugar, you wanna be my boyfriend?”

“Cut it out, Sherry,” Earl said. “Lester Ray, you fuckin that old woman yet?”

Lester Ray whirled on his heel. He stared at his father, at the two of them. They were both drunk. Their eyes were swimmy, and it was an effort for them to focus on him. The woman had flat circles of rouge on her cheeks, uneven and smudged, her face like that of some plump baby doll that had been discarded, thrown away in the trash. Her hair was an unnatural white, like a cloud around her head. He looked at his father, at his caved-in mouth that was framed in a crooked, self-satisfied mock.

“You ever say anything like that again,” Lester Ray said, “and I’ll ram that goddamed beer can down your fuckin throat.”

“Awww, come on,” Earl said. “I’s just makin a joke. Can’t I make a joke?”

Lester Ray’s disgust and anger bristled inside him. He could feel it, a physical thing, like a fist shaking inside his chest. He had most of his clothes in the pillowcase now. He almost forgot his red nylon jacket. He went over and took it down from a nail in the wall behind the door. He shoved it down into the pillowcase.

“Wait a minute, now,” his father said, “I want to talk to you.”

“Well, I don’t want to talk to you,” he said.

“No, listen now. There’s jobs for us over there at Crestview, at a new paper mill they’re buildin.”

“Fuck your jobs, and fuck you,” Lester Ray said. He started to move toward the door.

“Goddam you, boy, you can’t talk to your daddy like that,” Earl said, getting to his feet. He moved with surprising quickness to between Lester Ray and the door. “You better apologize, and do it now.”

“Apologize to you?! Don’t make me laugh.”

They were close together and Lester Ray could smell him, the biting stink of his body, the soiled jumpsuit he must have been wearing for days, the beer stale on his breath. His smells were coming out of his pores like sweat and mingling all over him until the rancid odor was simply him. It would be hard to know where his smell ended and he began. Lester Ray suddenly knew—it felt as though the fist that had been trembling inside his chest had abruptly dropped into his belly—that to him this was the smell of fatherhood, all the fathering and parenting he had ever known. It was a huge void that was only partially filled by Mrs. McCrory, who had nurtured him for his entire young life even though she was not blood kin, was not his mother and never could be. She was not obligated to do it, but she did. And he would pay her back and try to care for her in the only way he knew.

“I said, ‘apologize,’ boy,” his father snarled, “say you’re sorry.”

“Why don’t you apologize to me?” Lester Ray said.

“For what?”

“For every goddamed thing in my entire goddamed life.”

“Now fellas . . .” the woman Sherry interjected.

“Shut the fuck up,” Earl snapped at her, “this ain’t any of your business.” He peered at Lester Ray, his eyes narrowed to slits. Lester Ray knew his father was showing off, that he didn’t want to lose face in front of Sherry. Sherry, or whatever whore his father might be with at the time, was far more important than his own son. “You think you’re owed, don’t you, boy? You think the world, that I, owe you somethin because your mother was a fuckin whore, ran off and left her own little boy.”

“Leave my mother out of this,” Lester Ray said. He felt the burning of tears behind his eyes, and he did not want to cry. He would not cry. He had vowed he would never let his father see him cry, or anybody else if he could help it. He hoped they were tears of rage. Not the tears of the immense sadness that choked inside him, always.

“Shit,” his father said. “Well, I want to tell you somethin, boy, that I shoulda told you a long time ago. I ain’t your father. I wasn’t nothin but a dumbass boy, myself, stupid enough to take in a pregnant little old Gypsy girl, half colored is what she was. You didn’t know that, did you, Lester Ray? You’re part nigger, boy.”

“You’re lyin,” Lester Ray said. His father was inventing, making it up as he went. It was pathetic how desperately he was trying to justify himself.

“And soon as she got back on her feet good she was gone, leavin me with you, her part-nigger little love child.”

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Earl, tellin that boy somethin like that,” Sherry said.

“Didn’t I tell you to shut up, woman?!” He turned and cocked his fist at her.

“I’ll tell you this,” Lester Ray said tightly, “if what you say is true, then I’m relieved! I’m glad as hell you’re not my father. You’re nothin but a fuckin drunk.”

“I warned you, boy,” Earl said, whirling back around to Lester Ray. He was practically in the boy’s face. Lester Ray was taller than him by an inch, and they were looking eye to eye. His father’s face was flushed flame-red, sweat beading on his forehead and his upper lip. His eyes were wide and knifelike, stabbing at Lester Ray’s own. He reached out and shoved Lester Ray in the chest, causing him to stagger back half a step. The boy righted himself quickly.

It was something as unplanned and instinctual as a sneeze, so quick that it was over before he even knew he was doing it. The boy’s fist caught Earl on the mouth and nose and blood splattered as he went backwards, crashing against the wall. He slid down the wall and lay propped there, his head lolling to the side. Lester Ray had split his lip, and there was a lot of blood. His nose was probably broken as well. The front of the green jumpsuit was quickly covered with blood.

Earl did not move, his eyes closed. The woman let out a shriek. Then she stood next to the boy looking down at Earl. “You’ve kilt him,” she said.

Lester Ray was rubbing his knuckles, trying to massage away the stinging. “No,” he said, “he’s just passed out. I only helped him along a little.”

They stood there side by side for a few moments, gazing down at the inert, bleeding man on the floor. Then she looked at Lester Ray. Her face was broad and chubby, with her powder caked around her eyes and at the corners of her mouth. She smelled of flat beer and talcum powder and strawberry shampoo. She winked at him, an expansive gesture that she, in her drunkenness, probably thought was subtle. “Less you and me, sugar, git somethin goin while he’s dead to the world, whatayasay?”

It flashed into Lester Ray’s mind that this might be the very picture of his mother, that this would be the woman his father would choose, the whore, his mother; it was unbearable to think that he, Lester Ray Holsomback, had sprung from the loins of something this hideous. He stood looking into her tired face, at her flat yet yearning eyes. His mother could not be anything like this. It was impossible. No. “No,” he said aloud.

“Why not, baby?” she said, completely misunderstanding his negative.

And it took him a few seconds to fully comprehend her question. “Because,” he said, “you make me sick to my stomach.”

Mrs. McCrory found her suitcase, but she didn’t know what to put in it. She put in a doily that had been knitted by her mother, yellowed and limp, and then she took it out. “What would I do with that old thing?” she asked aloud, as though a companion were in the room with her. She picked up a fly swat and inspected it closely, trying to decide what it was. She tossed that in. She decided she’d best put in some clothes; all she had were the cotton house dresses, so she scooped a batch of them in her arms directly from the closet, with the hangers still dangling from them, and shoved them in. Her underwear. The boy’s wife had stolen all her panties. She didn’t wear brassieres anymore, nor corsets nor stockings, garter belts, things like that. She opened the drawer expecting it to be empty and saw all her panties there, most of them washed thin with sagging elastic. “She must have snuck in and put em back,” she said. “I would’ve given em to her if she’d asked.” She folded all the panties in with the dresses.

She found an extra pair of shoes, exactly like the ones she had on, black and chunky and comfortable. She put them in, along with a pair of her husband’s old bedroom slippers that she happened to spy in the closet when she retrieved her long cotton nightgown. Then she remembered her medicine. She found a brown paper sack and went into the bathroom and dumped all the medicines, the ones she was supposed to be taking now and some as old as six or seven years ago, into the sack. She put in a jar of Vicks VapoRub and a bottle of Jergens lotion. She grabbed a box of Carter’s Little Liver Pills, a box of Bayer Aspirin, and a bottle of Hadacol and put those in, too. She stood looking around for a minute. “Well then,” she said, “I’m ready.”

She lugged her suitcase into the kitchen and put it beside the door. She got the shoebox of money out of the pantry and set it on top of the suitcase. Then she took a long, last stroll around the house. There were lots of antiques, no telling what they were worth, but she reckoned Orville would find out soon enough. Her eye landed on something she didn’t think she’d ever seen before, a little polished mahogany box with a tiny figure of a ballet dancer in a pink tutu on the top of it. The dancer was standing on one toe, with the other leg stretched straight out. Her arms were raised gracefully over her head. Mrs. McCrory picked it up, and when she did there was a little “ting”sound. She turned it around, discovering a key in one side. It was a music box! She wound it and released the key, and the dancer began whirling around and around, while the music box tinkled out a song she’d never heard before. Until it came to her precipitately and without warning what the song was. It was “Let me call you sweetheart, I’m in love with you.” “Well, ain’t that the prettiest little thing,” she said, as the dancer went round and round, and she decided she would take it with her. She must have seen it before because she knew there was something significant about it, but she couldn’t recall what it was; sort of like when you wake up from a dream and you can’t remember what it was about but you know it was a nice, pleasant dream and you’d like to go back to it but you can’t.

She sat down in one of the kitchen chairs to wait for Lester Ray. She felt confident the boy would be able to drive an automobile safely, because he said he could. He told her he had taken it around the block a couple of times, after dark. He didn’t want anybody to see the car and get suspicious why it was all of a sudden up and running again. He had told her they were going to Pensacola, to the West Florida State Fair. She remembered going to the fair when she was a little girl, when it wasn’t much but some cattle and some prize hogs and some women’s pies and canned figs and such as that. There was always a barbecue contest. You could go around to the various pits and have a sample of the meat, or a little cup of Brunswick stew. The men would be sitting around the pit, passing a bottle of whiskey around, their cigarette smoke rising up to mix with the sweet-smelling smoke from the pit. She had loved barbequed pork, but she hadn’t had any for God knows how long. She and Lester Ray would stop at a restaurant and she would treat him to a barbecue sandwich or a slab of ribs.

She suddenly remembered something, so she got up and went into the hallway. She opened the coat closet and got her hat from the shelf. It was a dark blue straw hat with a tiny little cluster of red wooden cherries on the brim. It had been her church hat back before she’d stopped going. She laughed, thinking about the church: she supposed she’d lived too long, because all the preachers just kept saying the same things over and over again. She’d already heard everything ten times over. She figured she knew more than they did, anyhow. Most of them too young to blow their own nose.

She stood there in the hallway, holding the hat, looking curiously at it, because she could not understand what it was nor why she had it in her hand. Then she realized it was a hat. “Now whose hat do you suppose this is?” she asked the empty air. She put it on her head and looked in the mirror in the hall; she turned her head this way and then that way. She smiled at herself in the mirror. “Well, finders keepers, I always say,” she said. She went back into the kitchen and sat down again. She crossed her still shapely legs and folded her hands in her lap. She felt dressed to go on a trip with the hat on her head.

It had grown very dark as Lester Ray was crossing the backyard with his pillow slip of clothes—he had gotten his mother’s picture from where he had hidden it and put that in as well—when he heard someone. “Hey,” a voice said, barely above a whisper. It was a moonless night and very dark, and he could see nothing.

“Who’s there?” he said.

A willow bush started to shake. And someone stepped out from behind it. Even in the dimness Lester Ray could see the red dress. The girl just stood there quietly. “What you want?” he said.

“Where you goin?” Virgin Mary Duck asked.

“Is it any of your business?” Lester Ray replied.

“It might be,” she said. Her voice had a coquettish lilt to it, a flirtatious trill.

“You’re trespassin,” he said.

“So’re you.”

“What the hell do you want, girl?” he said, more harshly. “I ain’t got time to stand out here in the dark and argue with you.”

“I been watchin y’all,” she said, “you and that old lady. Y’all are fixin to go off somewhere in that car, ain’t you?”

“What’s it to you?”

“I want to go with you,” she said.

“Shit, don’t even think about it.”

“Listen here,” she said, coming closer to him. “I’ll be real good to you. I’ll suck your dick.”

“There ain’t any way you’re comin with us, so you might as well get on home,” Lester Ray said. She was making it tempting, with her last proposition, though she was far from the sexiest girl he’d ever seen, with those buck teeth and that pale red hair. But he couldn’t take any risks. He couldn’t, and he wouldn’t at this point even if she was the sexiest girl he’d ever seen, because he was focused on finding his mother and he wanted nothing to distract him from it.

“Listen, Lester Ray,” she said, coming even closer, “you got to hear me. I got to get away from him. He’s mean to me. Beats me. And he’s been fuckin me since I was six years old. Probably before that, only I can’t remember no further back than that.”

“Fuckin you? His own daughter?”

“Don’t make any difference to him. He’s a mean sumbitch, I’m tellin you.”

He could smell her now, her unwashed body. The cruelty that a man could inflict on his own children still amazed him, in spite of all he’d seen and experienced in his life. His own daughter! And her a halfwit midget to boot.

“Listen to me, V. M.,” Lester Ray said, “we ain’t got room . . .”

“I ain’t got no bag or nothin,” she interjected.

“ . . . and it’d be kidnappin. Your daddy would come lookin after us. Or send the law after us. We can’t have that.”

“Please, Lester Ray,” she said. “Please! I got to get away!”

“No, I said.”

“Look here,” she said, holding something out toward him. “Look what I got.” It was a bottle in a wrinkled paper sack. He pulled it out. He couldn’t read the label, but he knew it was whiskey, and from the weight of it the bottle was full.

“Who’s that out there in the yard,” came a voice from the back porch, from the deep shadows behind the wisteria. “Lester Ray?”

“Yes, ma’am, it’s me,” he said.

“That your wife with you?” Mrs. McCrory asked.

“No, ma’am, it’s not,” Lester Ray said.

The girl grabbed Lester Ray’s arm and he jerked it free. “Please,” she said, “just take me a little way down the road.”

“No,” he said. He handed her back the bottle of whiskey.

“You’d be savin my life, Lester Ray,” she said. “You would. Just like you was snatchin me from a fiery pit.”

“I got to go,” he said. He left her standing in the yard. He knew she wouldn’t leave. He was softening toward her in spite of himself and against his better judgment. Maybe they could take her as far as Pensacola, and then she’d be on her own. If they did take her, she’d have to understand that.

“Who you talkin to out there, then?” Mrs. McCrory said, when he came up on the porch, “if it’s not your wife.”

“Some little dwarf girl,” he said. “She’s beggin to go with us.”

“How’d she know we were goin anywhere? You didn’t tell her?”

“No, ma’am,” he said, “she figured it out. It was her daddy fixed the car.”

“Where’s her daddy now?” she asked.

“I don’t know. Probably laid up drunk somewhere.” He paused a minute. “He beats her,” he said.

“Well, let’s take her with us, then,” Mrs. McCrory said.

“It’s risky,” Lester Ray said.

“If she acts up and doesn’t behave, we’ll just put her out,” she said.

“I wasn’t talkin about that. The more people we got, the more folks might come lookin for us.” He and Mrs. McCrory stood gazing out into the dark yard. They could barely make out the reddish form. “And she stinks to high heaven,” he said.

“Well, bathe her.”

“Her clothes are nasty,” he said.

“Well, we’ll give her some of mine.”

“One of your dresses wouldn’t even come close to fittin her,” he said, “she’s a lot shorter than you.”

“You talk like she’s a midget or somethin.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, “she is.” He looked at the girl out in the yard. She seemed pitiful and alone. A small, lost child. But she wasn’t a child. She was a woman. He walked back down onto the grass.

“Y’all gonna take me with you?” she said anxiously.

“We’re gonna take you as far as Pensacola. Then you’re on your own. Now you got to get that clear, all right?”

“All right!” she said, and she tried to hug him, but she had the bottle in her hand and he skipped quickly away.

“Come on,” he said, “we’re gonna bathe you.”

“Bathe me? Why?”

“Cause you stink.”

“You gonna bathe me, honey?”

“No.” She followed him up onto the porch.

“Mrs. Mack,” he said, “this is Virgin Mary Duck.”

“I’m pleased to meet you, Virgin,” Mrs. McCrory said. “I’m gonna get one of my dresses for you to put on. Come on this way.”

“What’s wrong with my dress?” V. M. asked petulantly.

“It’s dirty, child,” Mrs. McCrory said.

V. M. followed Mrs. McCrory down the hall and into the bathroom. Mrs. McCrory turned on the hot water and the tub began to fill. “Is it a red dress?” Virgin Mary asked.

“I don’t think I have a red one. Maybe a nice pink one.”

“Shit. I don’t want no pink one.”

“Well, a blue one, maybe. I’ll let you pick it out.” They stood there while the tub filled up. Why, this is just a child, Mrs. McCrory thought. Lester Ray wants to take along a child, running away from home. I reckon he knows what he’s doing. The girl pulled her dress over her head and tossed it into the corner. Mrs. McCrory was startled. The girl had breasts, and a big bush of bright reddish hair down there. It was like seeing a full growth of pubic hair on an eight-year-old, with breasts to match. And the girl wasn’t much more than three and a half feet tall. She had a nice figure, but she was unfortunately ugly in the face. Well, Mrs. McCrory thought, she’ll probably grow out of it. Well, hell, what am I thinking? The girl is grown.

The girl climbed into the tub and sank into the water with a contented sigh.

“She ain’t no little girl,” Mrs. Mack said, when she returned to the kitchen. Lester Ray was drinking a cup of instant coffee.

“No, she’s not,” he said. “I told you, she’s a dwarf.”

“I thought you meant just little.”

“We’ll let her ride along as far as Pensacola, and then that’s it,” he said. “Whatever happens then, happens without her.”

“Why does she want to go with us?” Mrs. McCrory asked.

“I don’t know,” Lester Ray answered, “she just does.”

“All right,” Mrs. McCrory said.

The girl finished bathing and Mrs. McCrory helped her dry herself off. Virgin Mary picked out a green dress with little yellow flowers on it. It hung on her like she was a little girl playing dress up. They had to tie a big knot in the skirt up around her waist to keep it from dragging the ground. They were finally ready to go, and Lester Ray put his pillow case and Mrs. McCrory’s suitcase in the tiny trunk. He kept the bottle on the floorboard next to the driver’s seat. V. M. climbed into the back seat. She settled back. “All right, good lookin,” she said, “haul our asses off to Pensacola.”