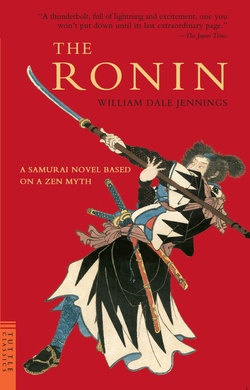

Читать книгу Ronin - William Dale Jennings - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWatching from the shadows….

The next village north called itself Hachiman’s Hunger in much the same way that, eight centuries later, another country would remember the places where its first president rested for the night. In turn, its neighbor on the north was named Tenth Verse Ox or, to stretch it for the wide screen, The Ox of the Tenth Verse, a name of fabulous meaning.

Because the third neighbor north was unusually distant and few had ever been there, the Ox people often had to take a breath before recalling its name. For this reason, it came to be known as The Place of the Forgotten Name even to those who lived there. It was in this third village that there lived three strong young boys who spent all the hours of their days dashing headlong toward manhood as if it really existed. They were the closest of friends, and all shared the same dream. At the age of eleven, they decided to become samurai, or professional swordsmen, in the train of some mighty daimyo.However childish the ambition, it was the correct age to start learning.

Of course, they never once considered the possibility that they might all three live out their brief lives as mere ronin or unemployed samurai wanderers of which there were thousands rejected by both Gen and Hei. Nor did it occur to them that their parents might begrudge this time stolen from the never-finished work in the fields, nor that the local master swordsman (retired) might refuse to accept them as students. He was a proud man and a genius by implication: few swordsmen of that time retired in the usual sense, and almost none reached his advanced age of fifty.

He did refuse to accept them and he refused repeatedly. The three knelt before him regularly once a week, and once a week he passed on by with his eyes on the horizon. So, adding strategy to respect, they took to kneeling directly in his path. After the loss of much dignity picking his way among young backs, the Master Swordsman was forced to notice them in self-defense. His first words seemed to end the matter before it began: “Have your parents consented? When they do, I shall listen to your applications.”

But boys of eleven, like girls of any age, are infinitely seductive. The tragic air of their complaints reminded the six parents that these were babies still, and that childhood imperatives are far briefer than childhood. They met in a Congress on Boys and mulled the question. Why not end the clamor with a few bruises from the Master himself? A dozen adept whacks over the head would certainly end the dream more abruptly than increased work in the field. The six agreed, men in the front room, women in the kitchen, and all fell to talking about the Rout of the Minamoto over a sip of rice wine.

Yet the Old Swordsman, like many bachelors, knew more of the hearts of boys than their ever despairing parents who know only their young behinds. He knew this was neither a childhood fancy nor brief. He saw the solemnity in their eyes as they beheld his sword, their consummate respect of his own person, and he knew that when they were alone on the mountain that they repeated old tales of Bushido to one another in soft voices.

He watched their religiously male young lives, saw their tremendous beauty, ripe bodies and shocking energy. And his heart cried out that such explosive life can prove joyous indifference to death only by courting it. With a passion that would have astonished their parents, he wanted to ruthlessly blot out the boys’ worship of cold steel, to see them disillusioned in him and their magnificent fire drowned in farming.

Toward this end and this end only, the Old Swordsman accepted them as students. There followed a four-cornered love affair that was all sadism, all masochism. He defeated them with a dainty flick of his wooden practice sword, methodically bruised and bloodied them, scorned the least hint of skill, taunted their mistakes, spat on their respect of him, and told them countless stories of stupid heroes who slashed to shreds other stupid heroes, and in turn were themselves opened wide to soak the indifferent earth.

The boys listened with wide eyes, and each determined to become a much wiser stupid hero. Eleven became twelve. Twelve became thirteen.

The Old Swordsman stretched tight his endurance attempting to utterly weary and discourage these infinitely energetic young boys. He flung deadly sarcasm into their faces as each stood embarrassed before his fellows, and gave them tasks that could not be done except at the expense of all else. He gave over all waking thought to his plot for destruction, and, helpless, saw himself devoured by this silent fury. Yet none broke and ran. They rose, wiped off the mud and looked up at him with trusting eyes that asked, “And now ?”

In despair, he ordered them out of his practice hall as hopeless. They had just become fourteen.

The three returned each day and sat on the Old Swordsman’s porch waiting for him to relent. One morning, unaware that he was home, the least talkative said, “He loves us and our blundering can only show him that none of us would live past that first real duel with steel. And he very kindly thinks that that would be a waste—as if all this has been just preparation and not living life itself. Now, when he takes us back, we must cease our childish play and finally begin to study, listen, work. None of us has yet really tried. If we had, we’d wear top-knots now and not be sitting on his porch. I intend to make him proud of me one day—even if I have to run away and learn by testing my skill with strangers on the road!”

Dropouts have always horrified teachers who feel their own institutions the best available—adding with preposterous modesty “at this time.” The Old Swordsman instantly fled to the mountain for nine days, and examined his own wisdom carefully. Finally deciding that he himself had been the youngest of the four, he returned with grim determination putting heel-thuds in every step. If he couldn’t save these boy-men from glorious vivisection, he would at least postpone it by making them the most superbly adept fools in the dress of samurai. He would set to work in dead earnest to divide all he knew, the whole of his life and the sum of his experience, into three.

Without expression, the boys knelt before him. There was no reason to be delighted at the sight of him; they’d known that he would return. They rose and began to study in young fury. Without superfluity in word or gesture, the Old Swordsman taught them in that same cold fury. They practiced unremittingly like the quietly insane, as insanely welcomed hardship, and rose before each dawn to sit in meditation. Loved by themselves and authority, they were kind, honest and truthful. And, though they seldom laughed aloud, there was an immense zest in all they did.

With grave joy, the three exchanged seed, resolutely keeping their samurai oath of female abstinence with the ease of the inexperienced. Their oneness reminded the Old Swordsman of the legendary harpist of great skill who cut the strings of his harp upon the death of that lover who was his most skilful listener.

He sat in the shadows and watched them rush through their lives to that destination which is the twin of birth. They had become fifteen.

Each hour gave the three greater skill. Their names came to be known throughout The Place of the Forgotten Name.Then word spread south to The Ox of the Tenth Verse, then more south to Hachiman’s Hunger. And beyond. Yet, as is proper, it never reached the practice hall.

Word came suddenly. The Old Swordsman’s last remaining brother had been murdered in a village to the south where his little temple stood. He seemed to have invited his fate, but the fact remained that some wandering ronin had cut him clean in two for no really satisfactory reason.

Before the Old Swordsman could realize that this was supposed to be a loss, his three young students vanished. They left a short, respectful note. The three swords missing from Sensei’s collection were, of course, only borrowed. They would be returned in honor. They regretted leaving without permission but time would brook no delay. And other such youthful expressions.

As if cleaved from head to heart, the man opened his mouth and gave a great and silent cry. While the note was still settling to the floor, he swept up his sword from its stand and set out down the path. He left food in a pot over the fire and the door open. For the first time since his initial duel, he was afraid.