Читать книгу The Unmaking of a Mayor - William F. Buckley Jr. - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword Foreword

OUR TEXT TODAY is a pair of classic Buckley quips from the great 1965 vintage. People who remember nothing else about William F. Buckley, Jr.’s, brief foray into elective politics recall his reply when asked what he would do if elected Mayor of New York. He would “demand a recount.” And they remember, as well, his response when asked how he felt as he emerged from a meeting with the editorial board of The New York Times. He felt as if he had “just passed through the Berlin Wall.”

Somewhere in my attic is a photograph of Bill’s introductory press conference. He is grinning wolfishly, and I am wincing in pain. He has just been asked what he would do as his first act of office, and we both know what’s coming next. He had come up with the “recount” crack a few weeks earlier, and I had urged him not to use it in public. It was a Buckley-grade witticism, to be sure, but it was not likely to be good for unit morale. But Bill was a writer and not a politician, which is to say that he was constitutionally incapable of letting a great line go unused. He thus proceeded to roll it across the pressroom with perfect timing and to predictable effect. Merriment bounced off all four walls.

As we all have come to learn, painfully or otherwise, japes have consequences. Before even the first news cycle had expired, a press narrative had begun to take shape: namely, that Bill’s campaign was something of a lark, some elaborate form of self-entertainment. In the dismissive parlance of the day, Bill’s was “not a serious campaign,” whatever that might be. Our fundraising receipts, never torrential, slowed to a dribble and the volunteer effort flagged. The Buckley for Mayor campaign was off and limping.

What turned it around, I would like to report, was the incandescent performance of our candidate; ingenious stratagems devised by management; and a flawless, five-borough ground game executed by our vaunted field operation. It would be more accurate to say, however, that what turned the campaign around was a scheduling quirk.

In the early days, before we had learned a thing or two about crowd management, we felt free to expose Bill to large groups of self-selected citizens. Most of these exchanges were high-minded, even civic-virtuous in tone. But when an ideological match touched dry tinder, a raging rhetorical fire could break out. One meeting with a group of excitable feminists, for instance, became a high-decibel, low-information event, and I had no ready answer when Bill asked me later, “Remind me why we did that, would you?”

On another occasion, Bill and I found ourselves the only whites in a large room packed with angry black voters. They were angered by what they perceived to be Bill’s unthinking support for a racist police force, the NYPD. Needless to say, the game was on.

Back and forth they went. Bill and his audience talked about crime. Black crime. Black-on-white crime. Black-on-black crime. And they talked about leadership. Community leadership and moral leadership. It was a long, hot ninety minutes, and Bill sweated through his preppy, blue button-down, the stains spreading down his flanks. Discount this judgment for sycophancy if you like, but he was magnificent. By the end of the meeting, something had changed.

There remained not a single person in that room who thought Bill’s views on race and crime were unthinking. He was deeply informed and maintained an intellectual clarity throughout the raucous colloquy. His audience listened to him, and they gave him their respect, if not their support.

For his part, Bill became a changed candidate. As a polemicist for a little magazine, he had been poking Liberal shibboleths through the bars of a cage. As a candidate on the big stage, he was poking those shibboleths from inside the cage. There was no place to hide now. He was fighting for his public life.

There were two other changes that day. The first occurred within and around our security detail. Now, I can’t say with any confidence whether it happened that day or a month earlier or a month later, but I can say with absolute certainty that in the summer of 1965 the NYPD fell in love with Bill Buckley. I don’t mean just the Irish and Italians, either, but the black, Hispanic, and Asian cops, too. Bill was stating their case with eloquence and verve and doing so at a time when few other public figures would stand with them. (Not unlike today, in 1965 there were reputable people and reputable publications that claimed to believe that one of the principal causes of urban crime was police misconduct. Not unlike today, those claims were evidence-free and ideologically powered.)

The cops’ support for Buckley for Mayor, which soon spread to the firemen, and to some of the building trades, had two effects, one long term and the other proximate. To my eye, which is by now experienced if still unscholarly, the long-term effect of the NYPD-WFB alliance ran in an almost unbroken psephological line through the blue-collar support for Johnson and Nixon during the Vietnam War, thence to the Reagan Democrats of the early eighties and, ultimately, to the “values voters” of today—the people who vote not with their class or race or gender but with their patriotic hearts. A significant development, that.

The proximate effect of NYPD support seemed more important. As some of you will remember about the sixties, and the rest of you will have read, the public square could be a dangerous place. Political figures who stirred dissent beyond the edge of consensus could, and not infrequently did, excite gunfire. John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, George Wallace, Robert Kennedy, and others less well known were all gunned down at or near public events. Bang, you’re down.

When Bill Buckley died peacefully at his Connecticut home in 2008, the news of his passing was met by an outpouring of admiration and unfeigned affection. By that time, manifestly, he had become America’s favorite Conservative, beloved by his many followers and respected by his few public foes. Times change, happily. When he ran for mayor in 1965, Bill was not yet Mr. Nice Guy. He was, rather, a right-wing insurgent marching against the citadel of self-satisfied liberalism . . . and the denizens of the citadel were not amused. To put the matter carefully, Bill was a controversial figure.

(There is an apostrophic point that must be made here. It should be remembered that Bill Buckley was conservative long before conservatism was cool. In 1965, he was not seen to be the charming, white-shoe Yalie that retrospective analyses have portrayed. He was, in the contemporaneous view, a black-shoe cop-lover, fronting for dark forces that the elite media professed to fear: he was the “tip of the spear” of a reactionary Right. So let us pause here to salute those who joined our cause in the early days, when the historical outcome could not be known and the risk to professional reputation was palpable. Let us pause to salute Jim Buckley, who played flawlessly the role he was born to play—older and wiser brother of the candidate—and Don Pemberton (our indispensable man in Brooklyn) and Art Andersen (who kept our books almost balanced) and Aggie Schmidt (Bill’s tireless amanuensis) and Phil Nicolaides and Geoff Kelly (our ad-making Mad Men) and Kieran O’Doherty (the Conservative Party stalwart who worked himself to the very cliff of cardiac incident) and Marvin Liebman (who produced our rallies and carbonated our staff meetings) and the sturdiest warrior of them all, William Rusher (he of the Princeton and Harvard pedigree who gave his aging mother palpitations by departing a Wall Street law firm for a little magazine with only a tenuous grip on respectability). These were the winter soldiers of our revolution. Times change, happily. Only a few years later, by which time Bill had become the toast of the town and his wife, Pat, began to adorn the Best Dressed lists, it had become de rigueur to embrace the advice Nixon had famously abjured and do the easy and popular thing, which was to make your way briskly into the fabulous social circle of Bill and Pat Buckley.)

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise for us to review the thickening file of threats made against Bill. It shouldn’t have, but it did, anyway. The reports were hair-curling. The stone canyons of New York City seemed to be crawling with bloody-minded crazies, many of them on a mission from one higher power or another. (I note for the record that I was more rattled by these reports than was our imperturbable candidate. To borrow Ben Bradlee’s description of one of his notably intrepid reporters, Bill clanked when he walked.)

What lifted our spirits (and lowered staff blood pressure) was a follow-on briefing by an emissary from the NYPD. The cops were all in, thoroughly prepared to take fast, discrete, professional action in whatever contingencies might arise. Nobody was likely to mess with a single hair on the head of their man Buckley. File closed. As was his habit, the best summary line came from Bill Rusher, who sat in on one of the threat meetings. Said Rusher of the crazies, “I’m beginning to feel sorry for these poor bastards.” By Labor Day, everything was copacetic. We had come to feel that the safest place in all of New York City, safer even than Grand Central Station at straight-up noon, was to be standing next to Bill Buckley at a campaign event.

There was another change. It took place, asymptotically as Bill might have described it, among our regular press corps, some of whose members were grumpy about their assignments to our campaign. (Campaign coverage in those days was assumed to be a ticket to a regular gig at City Hall, with the winning candidate pulling in his own beat reporters. There may have been a conflict of interest in there somewhere.)

Early on, the press was of one mind, with their impressions of the principal candidates frozen in presupposition. John Lindsay? He was tall (agreed), he was liberal (do tell), he was mahvelous (until he opened his mouth), and he was destined to win (yeah, probably). Abe Beame? He was a colorless bureaucrat and a machine Democrat (no argument there). Short in stature and shorter still on charisma (nor there), he had a fighting chance, at least if the unions got in gear (conceivably, I supposed). Bill Buckley? He was a Creature from the Hard Right Lagoon, his chances pegged between slim and none and doubtless closer to the latter (WFB concurring, alas). Presuppositions are a durable barrier against improved understanding. They died hard.

But while our regular press gaggle may have come for the gotcha patrol—that cold-stare vigil for the verbal slips that could be inflated into categorical slurs against women, gays, blacks, Jews, Latinos, Asians, fat people, short people, or variously challenged people, not to mention commonsense-impaired people—they stayed for the bons mots that Bill sprinkled around promiscuously, as if they were bead necklaces tossed from a Mardi Gras float. Bill was good copy. And it didn’t hurt that he was running against Beame, five feet five inches of banality, and Lindsay, six feet three inches of vapidity. (Beame and Lindsay seemed to be quotable only when quoting Bill, usually in high, theatrical dudgeon.) The press couldn’t help themselves. They liked Bill. Some of them even became his pals. (It was during the campaign that Bill became lifelong friends with the great Murray Kempton, who, while he wrote for a down-market lefty rag, seemed to reserve special affection for the candidate who persisted in talking over the heads of his proletarian readership.)

There was something else. The press noted and was impressed by Bill’s courage. His courage, that is, in both its physical and moral forms. It was Bill and only Bill who waded into those last-man-standing bouts in halls stuffed with red-faced citizens. While Beame and Lindsay were surrounded by platoons of handlers, who busied themselves clearing voter-free paths for the great men, Bill was lucky if he had me and an off-duty cop in tow. The press noticed.

Again, I can’t tell you which hour of which day it happened, but the press narrative began—finally—to shift. At first a few reporters, and then more, and then at last the full mewling herd began to concede that maybe, just maybe, Bill’s was a serious campaign. One reporter, the legendary McCandlish Phillips of The New York Times, began to toy with another idea. Perhaps Bill’s was the only serious campaign.

Then there was that meeting at the Times, the one behind the Berlin Wall. This was 1965, remember, in a land far away. The Times may have been only one of seven New York daily newspapers (not counting the Wall Street Journal, which was considered a trade publication in those days), but its stature was belied by the blandly taxonomic term primus inter pares. The Times didn’t just open and close Broadway shows and puff up and snuff out political aspirants. It set the agenda for municipal discussion—and then coined the vocabulary in which it would be conducted. In terms of mass mind control, there is nothing in contemporary culture with which to compare the dominance of the sixties-era New York Times.

When Bill Buckley strode into that editorial board meeting, he found himself surrounded not just by the editorial writers who would craft the paper’s endorsement and the executives who would put their chops on it but also by reporters and editors from the principal beats—transportation, education, housing, health care, and the rest. Bill was surrounded, if you will, by contemporary liberalism’s A-Team. The next two hours would prove to be a real education. For them.

This is unsubstantiated surmise on my part, but that meeting may have been the first time in their lives that most of the Times-men had faced an articulate and informed Conservative in close encounter.

In support of that surmise, I offer only this shred of evidence. In 1965, the platform of choice for opinionmongers was neither a cable-news slot nor a radio talk show. It was the syndicated newspaper column. In the mid-sixties, there were hundreds of nationally syndicated features, three of which—three!—that could be fairly described as conservative. There was David Lawrence, the grand old man of US News & World Report, who was by that stage of his career more old than grand. There was James Jackson Kilpatrick, the clarion voice of southern traditionalism. And there was William F. Buckley, Jr., the leader of an emerging national conservatism. Bill Buckley was the new-new thing.

Bill did not, of course, win the endorsement of The New York Times. But he won the argument. And everybody in the room knew it.

I am still contacted from time to time by people who have stumbled upon, and then become fascinated by, the Buckley campaign of 1965. Historians, political scientists, city planners, journos, pols. They sense that something special happened, something heuristic. One conversation with an eager-beaver thesis writer, according to my notes, went this way:

EBTW: Mr. Freeman, can you confirm that the Buckley campaign issued twenty-two policy proposals?

NBF: No, I can’t confirm that, but it sounds ballparkish.

EBTW: Can you confirm that twenty of those proposals were subsequently adopted by New York mayors—many by Giuliani, some by Koch, and the remaining few by Bloomberg?

NBF: No, but you may well be correct.

EBTW: You don’t sound surprised.

NBF: No, not at all.

Well, that’s the essence of our story, isn’t it? Why were we not surprised by the serial successes of the Buckley campaign? We were not surprised, I would submit, because we recognized that what Bill Buckley was preaching in 1965, and what he would practice for the rest of his life, was the politics of reality: the certain knowledge that, over the course of time and under the weight of experience, ideological abstraction will yield ultimately to either the obdurate facts of public finance or the timeless imperatives of the human spirit. One or the other. What Bill Buckley taught us was that there is not only a conservative way to raise the young and care for the old. There is a conservative way to collect the garbage and shovel the snow.

It’s been fifty years now since Bill Buckley demanded a recount. Perhaps we owe him one. So let’s pop the big one—who really won that race back in 1965? The best answer to that question may be another question. Is anybody publishing an anniversary collection of the speeches and papers of John Lindsay or Abe Beame? Anybody? Anybody?

Shortly after Election Day, Bill invited me to a postprandial meeting at the New York Yacht Club. Something was up. Bill held all of his important meetings off-site, as the walls of NR’s warren-office had ears, and the interruptions were incessant.

I had picked up a rumor that Bill would be moving to Switzerland to take on what we had long referred to as the Big Book. For several years past, Bill had been urged by both mentors (Willmoore Kendall and others) and protégés (me and others) to write a serious work of political philosophy, a Big Book that would make Bill’s bones as a heavyweight intellectual. Journalism was fine, we thought, but scholarship was better: a Big Book was exactly what was needed to undergird Bill’s burgeoning career as he reached age 40. We even had a title teed up, The Revolt Against the Masses, with the book intended as a rebuttal-cum-extension to Ortega y Gasset’s classic work The Revolt of the Masses. I was intrigued. Perhaps what I needed as a restorative was a bit of head-clearing, long-form work.

Bill and I had a drink and began to swap campaign stories, at one point laughing so hard that a Club employee was dispatched to restore house decorum. Good luck with that. It was a time for laughing.

As a second drink arrived, Bill turned to business. He reported with enthusiasm that a publisher had offered a handsome advance for a book on the campaign. Bill wanted to do it, both to inscribe the record indelibly and, I suspected, to relitigate some of the campaign spats. He said that I would be “indispensable” to the project and outlined a generous financial arrangement, ski passes very much included.

I don’t know if my heart sank, but my shoulders sagged. The last thing I wanted to do was to wallow in campaign minutiae for another four or five months. I had raccoon eyes and needed to get my teeth fixed and get my license renewed and begin the citywide search for the dry cleaner who was holding my clothes in some undisclosed location. If Bill had offered me the seventy virgins of martyrdom, I would have countered at thirty-five. I needed a break.

I loved Bill, and I hated saying no to him, but this was a mission for which I could find no motivation. So after two years of dawn-to-dinner collaboration, we agreed to go our separate ways, he to do the campaign book and I to develop a television project. The meeting did not end well.

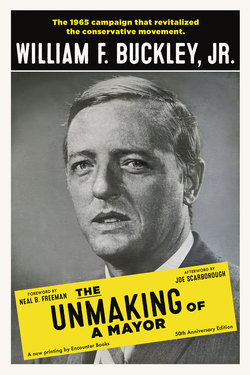

But the story did, almost serendipitously so. While he may have set off to write a quickie campaign book, what Bill came back with was The Unmaking of a Mayor. Here we are a half century later and people who would understand American urbanology or the history of New York City or the beginnings of the modern Conservative movement still feel obliged to read and ponder and come to terms with it. Over the course of his hyperproductive career, Bill wrote fifty-four books—all of them readable, many of them consequential, one of them a classic. Unmaking became, quite inadvertently, Bill’s Big Book and cemented his reputation as a public intellectual of the first rank.

The television project worked out, too. The series debuted in the spring of 1966 as Firing Line, hosted by William F. Buckley, Jr., and it ran for more than thirty years.

NEAL B.FREEMAN

Amelia Island, Florida

April 2015

Postscript

In my personal calculation, Bill’s signal contribution to A.D. 1965 was to introduce me to his new office manager, Miss Jane Metze of Harriman, N.Y. She was highly attractive and a constant distraction, a distraction, in fact, to which I have chosen to ascribe all responsibility for the rookie mistakes recounted in this volume.

There were rivals for the attention of Miss Metze. Being a charitable sort, I will leave the married celebrity unnamed. Of the others, the most formidable was the journalist John Phillips, a big, rawboned fellow with hands that could palm basketballs. A diligent reporter and a fine writer, his copy made for good reading. Until one morning, that is, when lingering over a campaign breakfast of coffee (black) and pizza (cold), I came upon a reference to Miss Metze as a “honey blonde with an oozy voice.” Really, John!

When he showed up at headquarters that morning, I accosted John, pushing the newspaper into his chest and saying in a voice louder than necessary, “This is beneath even you, John. Using The New York Frigging Times as a dating service!” My sworn testimony is that the legendary John Phillips, who wrote under the fancy-pants byline McCandlish Phillips . . . blushed.

On an impulse never regretted, Miss Metze and I were married on a cold day in March 1966. Bill was still in Switzerland, dashing down mountains and dashing off books. Just before the service was to begin I received a telegram. It was signed by General Pulaski and it read “I won’t be attending your wedding if you won’t attend my goddamn parade.”