Читать книгу General Wauchope - William F.S.A. Scot. Baird - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER III

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

ENTERS THE ARMY—THE BLACK WATCH—ASHANTI WAR—RETURN HOME—BANQUET AT PORTOBELLO.

Young Wauchope had not long to wait for a commission. At that time positions in the army could only be got by purchase and strong influence, but he was fortunate in being enrolled as ensign, in November 1865, in the 42nd Highlanders, one of the most popular and distinguished of Scottish regiments, and familiarly known as the 'Black Watch.' He was only nineteen years of age at the time when he joined the regiment at Stirling Castle, and is described by one of his superiors as then 'a merry, rollicking lad, full of life and fun.' 'Andy,' as he used to be called by the officers, and 'Red Mick' more frequently by the men, was a general favourite; and, notwithstanding his natural lightness of heart, he had soundness of brain and judgment enough to know that promotion would only come to him by diligent study and close application to his profession. His commanding officer, Sir John M'Leod, appears, at all events, to have been struck with the young man's energy of character and indefatigable 'go,' for he describes him as at that time 'a particularly energetic young lad, who thought nothing of walking from Stirling to Niddrie to see his old father whenever he could get a few days' leave at a week-end.' This, he explains, was not at all from motives of economy, 'but merely to walk off superfluous energy.' Assiduous in the matter of drill, Wauchope soon became as proficient as his instructor, for he took a thorough pleasure in the exercise. The innate smartness and recklessness of the red-polled ensign at once endeared him to a grave old Crimean drill-sergeant, who forthwith charged himself with his training. Concerning this latest accession to the commissioned strength of the Black Watch, the man of stripes was wont to say—'That red-headed Wauchope chap will either gang tae the deil, or he'll dee Commander-in-Chief!'

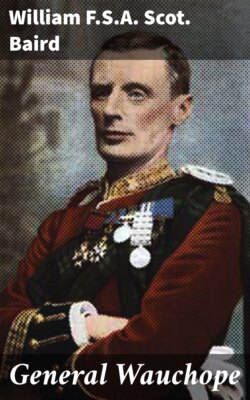

The Black Watch

Though the worthy sergeant's prediction has in neither case been verified, young Wauchope, though at first inclined to consider his superiors a trifle slow, soon fell into the steady sober ways of the 42nd, then as now noted for the gentlemanly conduct of its officers, and the upright character of its rank and file. 'Step out, shentlemens; step out. You're all shentlemens here; if you're not shentlemens in the Black Watch, you'll not be shentlemens anywhere.' Such was the opinion of their old Highland sergeant as he put them through their drill. We have been told that at that time one might be a year among the officers and never hear an oath uttered, while smoking and drinking were scarcely known. Wauchope was thus fortunate in being, at a critical period of his life, associated with men who shunned what was vulgar, and whose influence over him was for good. In military matters he early manifested the inquiring mind. Points in drill or tactics, which he might not at first understand, set him thinking, and he would not rest till he got an explanation of their meaning and object. Captain Christie, then adjutant of the Black Watch, lately governor of Edinburgh Prison, was early taken into the young ensign's confidence in difficulties of this kind. Having been through the hard fighting and the terrible scenes of the Indian Mutiny, the captain was made frequently to 'fight his battles o'er again,' explaining the methods and tactics by which decisive results were attained in the various engagements. Never what may be called a great reader of books, Wauchope had two, however, placed in his hand by his adjutant when in Stirling Castle, which he studied assiduously. These two books—Macaulay's Essays and Burke's French Revolution—he read and re-read, borrowing them several times, and there is little doubt that the perusal of them made a deep and lasting impression upon his mind, going a long way towards the formation of that strong political sagacity, administrative ability in civil affairs, and military genius which were displayed on many occasions in his after-life.

In 1867 Wauchope went to Hythe, where he passed in the Military School of Instruction first-class in musketry, and in June of that year was promoted to be lieutenant. So proficient was he found in the matter of drill that, in spite of his youth, he was appointed to the important position of adjutant to the regiment in 1870, though still retaining the rank of lieutenant, a position which he held with the utmost credit for the next three years. During this time he served successively with the 42nd in garrison duty at Edinburgh, Aldershot, and Devonport.

Leaving Edinburgh in 1869 by the transport Orontes, from Granton to Portsmouth, the regiment reached Aldershot camp on the 12th November, and was stationed there for two and a half years. After taking a part in the Autumn Manoeuvres at Dartmoor in August 1873, they were stationed for a few months at the Clarence Barracks, Portsmouth. His duties during all these years were of the most arduous and trying description, but his singularly lovable and attractive nature made him so many friends that difficulties disappeared before his cheerful countenance. Speaking of this period in his career, Colonel Bayly, afterwards his commanding officer, says—'It was very early in his subaltern career that Wauchope was voted for the appointment of adjutant, and he made one of the best that had ever been appointed. His charm of disposition enabled him to gain the love of his men, whilst his tact and firmness enabled him to enforce the necessary discipline.'

Ashanti war

On the outbreak of the Ashanti war on the west coast of Africa in the autumn of 1873, young Lieutenant Wauchope found his first opportunity, in active foreign service, of showing the metal of which he was made.

The king of Ashanti—Koffee Kalcallee—the head of a strong warlike kingdom on the north of the Gold Coast, had long asserted his authority over the neighbouring provinces of Akim, Assin, Gaman, and Denkira, down to the very coast where the Dutch and English had settlements. The transfer, in 1872, of the Dutch possessions adjoining Cape Coast Castle to Great Britain for certain commercial privileges, gave King Koffee of Ashanti the opportunity for asserting what he considered his lawful authority over the Fantees or adjoining coast tribe. This, however, was only a covert excuse for striking a blow at British rule on the Gold Coast, and in January 1873 an army of 60,000 warriors—and the Ashantis, though cruel, are brave and warlike—was in full march upon Cape Coast Castle and Elmina. The British force on the spot under Colonel Harley was only a thousand men, mainly West India troops and Haussa police, with a few marines; and though the neighbouring friendly tribes, whose interest it was to remain under the British protectorate, raised a large contingent for their own defence, this was a force that could not be relied on. By the month of April the Ashantis had crossed the river Prah, the southern limit of their kingdom, and were within a few miles of Cape Coast Castle, and matters were looking serious. With the aid of a small reinforcement of marines, the enemy were fortunately kept at bay until the 2nd October, when a strong force arrived from England, which turned the tide against King Koffee, and ultimately swept him and his warriors back upon his capital. This expedition, under Major-General Sir Garnet Wolseley, with his staff and a body of five hundred sailors and marines, not only held their own, but by the end of November, after much hard preliminary work, had forced the king to retreat to Kumasi. Wolseley, finding the expedition a more arduous one than was at first expected, had meantime asked for further reinforcements, and on the 4th December the Black Watch, accompanied by a considerable number of volunteers from the 79th, left Portsmouth, arriving on 4th January 1874 at their destination. Sir Garnet had now at his disposal a force consisting of the 23rd, 42nd, and 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade, detachments of Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, and Royal Marines, which, with native levies, formed a small but effective army wherewith to advance into the enemy's country.

This was no light task, more especially when the dangerous nature of the climate is taken into account, and the necessity there was that the enterprise should be accomplished, if at all, before the rainy season, with all its concomitant malaria, set in. To pierce into the heart of a country like Ashanti, with its marshes and matted forests, its pathless jungles and fetid swamps, with a cunning foe ever dogging their steps, was the service imposed on this brave little army of British. As Lord Derby remarked at the time, this was to be 'an engineers' and doctors' war.' Roads had to be made, bridges built, telegraphs set up, and camps formed. But by the energy and skill of General Wolseley, ably supported by such men as Captain (now Sir) Redvers Buller, Colonel (afterwards Sir John) N'Neil, Lieut.-Colonel (afterwards Sir Evelyn) Wood, Colonel (now Sir John) M'Leod, and others who have since risen to distinction in the army, the enterprise was successfully and brilliantly accomplished within a month. The Ashantis were forced back upon their own territory in a number of engagements, until at last their capital was seized and burned to the ground.

Wauchope's black boys

Lieutenant Wauchope's share in this expedition was highly creditable to his bravery and military skill. Accompanying Sir Garnet Wolseley at an early stage of the struggle, as one of the staff, he resigned his adjutantship of the Black Watch, and was afterwards fortunate in obtaining special employment as a commander of one of the native regiments formed at Cape Coast Castle, namely, Russell's regiment of Haussas, the Winnebah Company. To form such crude material into a well-disciplined body of soldiers seemed at first a well-nigh hopeless undertaking. Their fear made cowards of them all. The very sight of a gun terrified them, and for long they held their arms in such superstitious dread, that they would hang them up in the trees and actually worship them. But Wauchope's admirable drilling qualifications stood him in good stead. He took, we are told, a great pride in the training of his 'black boys,' as he called them, and infused into them much of his own daring spirit. This appointment separated him for a time from his own regiment, but on the Black Watch arriving afterwards at the Gold Coast, he had frequent opportunities of fighting by their side.

In the advanced guard, the 42d Regiment and Russell's Haussas, under Colonel M'Leod, having crossed the Adansi hills, reached Prah-su on the 30th January, and occupied a position about two miles from the Ashanti main position at Amoaful. Surmounting innumerable difficulties, and carrying all before them, the Highlanders by their dash and intrepidity were a splendid example to those led by Wauchope, who sometimes had difficulty in inspiring his men with courage enough to face their much-dreaded enemy. In scouting and clearing the ground his men were, however, invaluable, and if we consider the dense undergrowth that covered the country traversed, this was a work of great importance. By one traveller we are told 'the country hereabout (at Amoaful) is one dense mass of brush, penetrated by a few narrow lanes, where the ground, hollowed by rains, is so uneven and steep at the sides as to give scanty footing. A passenger between the two walls of foliage may wander for hours before he finds that he has mistaken the path. To cross the country from one narrow clearing to another, axes and knives must be used at every step. There is no looking over the hedge in this oppressive and bewildering maze.' It was in such a position as this that the battle of Amoaful was fought. The enemy's army was never seen in open order, but its numbers are reported by Ashantis to have been from fifteen to twenty thousand. After a stubborn day's fight in the entanglement of the forest, the Ashantis were finally defeated with great loss.

Attack on Kumasi

On the 1st February, the day following this important engagement, orders were issued for an attack upon Becquah, towards which Captain Buller and Lord Gifford scouted at daybreak. The attack was intrusted to Sir Archibald Alison, who had under his orders the Naval Brigade, one gun and one rocket detachment, Rait's Artillery, detachment of Royal Engineers, with labourers, 23rd Fusiliers, five companies of 42nd Highlanders, and Russell's regiment of Haussas, with scouts. This force was divided into an advanced guard and main body, and Wauchope was again honoured with the post of danger, his regiment of Haussas being in the advanced guard along with the Naval Brigade and Rail's Artillery, all under the command of Colonel M'Leod. After a toilsome march through the bush under a tropical sun, the town of Becquah was reached, and a sharp but decisive engagement took place, the main brunt of which fell upon Lord Gifford's scouts and the Haussas. Still pressing on, the intrepid little army, through many mazy trampings, arrived at Jarbinbah, every inch of the ground being disputed by the enemy. Here Wauchope was wounded in the chest by a slug fired down upon him from one of the tall trees in the swampy ground in front of an ambuscade; but, serious enough though it was, and causing much loss of blood, it did not prevent him sticking to his post and looking after his 'black boys.' After this battle King Koffee sent in a letter to Sir Garnet Wolseley, with vague promises of an indemnity, hoping to prevent the invading army approaching his capital; but his previous prevarications did not admit of his tardy proposals being for a moment entertained. The king, realising this, resolved to dispute the passage of the river Ordah. The stream was about fifty feet wide, and waist-deep, and the enemy, to the number of at least 10,000 men, were posted on the further side. Russell's regiment of Haussas was, on the afternoon of the 3rd February, at once passed to the other side of the stream as a covering party to the Engineers, who were ordered to throw over a bridge. They rapidly made entrenchments, and cleared the ground on the north side, so that the whole advanced guard might successfully cross. In this affair Lieutenant Wauchope acquitted himself with much coolness and bravery, notwithstanding his wounded state, Colonel M'Leod reporting the regiment as 'being in front the whole day, and having behaved with remarkable steadiness under trying circumstances, reserving their fire with remarkable self-control.' This shows a decided improvement in the discipline of Wauchope's 'black boys' from a former despatch, where their firing was characterised as 'wild.' By daybreak on the morning of the 4th February the bridge over the Ordah was completed, amid drenching rain, which had continued all night, and the whole available force was successfully passed over in spite of the vigorous resistance of the Ashantis, who, with drums beating and great shouting, were endeavouring to circle round the British. 'For the first half-mile from the river the path rose tolerably even,' says one report; 'then after a rapid descent it passed along a narrow ridge with a ravine on each side; dipped again deeply, and then finally rose into the village. To the south-west of the village, extending almost to the village itself, and for a considerable distance along the road, the enemy had made a clearing of several acres, by cutting down a plantain-grove. Colonel M'Leod steadily advanced along the main road under cover of a gun, after a few rounds from which the Rifles made a corresponding advance; then the gun was brought up again, and another advance made; and in this manner the village was at last reached and carried.' The Ashantis fought well, and with a vigour and pertinacity which won the praise and admiration of the Highlanders. The soldiers were put to their mettle, and even the Haussas, as if catching the fierce courage of the Scotsmen, laboured with vigour and energy not eclipsed by any in the field. The dislodgment of the enemy was not effected, however, without considerable loss, Lieutenant Eyre being killed, while Wauchope received a second severe wound, this time on the shoulder.

Kumasi captured

The battle virtually decided the fate of Kumasi and King Koffee. On the news of the defeat of his army the king fled, no one knew whither, and the victorious General Wolseley, with his troops, entered the blood-stained capital in the evening. Attempts were made to negotiate with the king. He preferred to keep in hiding, and after two days' stay in his capital in order, if possible, to compel him to come to terms, it was at length resolved to destroy the place and at once retire to Cape Coast Castle. Kumasi was burned to the ground on the 6th February, and the British troops having accomplished their purpose retraced their steps, and notwithstanding the swollen state of the rivers—for the rainy season had just set in—their destination was reached in twelve days. No time was lost in getting the troops out of the influence of the deadly climate, and accordingly by the 4th March the whole expeditionary force was embarked for home.

Wauchope's wounds, thanks to a good constitution, readily healed, and by the time of his arrival at Portsmouth he was fairly convalescent, though every effort made to extract the slug had been unsuccessful. He left his favourite Haussas—his 'black boys'—with every manifestation of regret, at Cape Coast Castle. Nor was the regret only on his side, for we learn from one of his brother officers that 'they looked up to him as a father, and would willingly have followed him through any danger, even to death itself.'

Home again

For his conspicuous bravery in the various engagements in Ashanti, Sir Garnet Wolseley's despatches brought Wauchope under the favourable notice of the Government, and he was awarded the Ashanti medal and clasp. On the return of the troops, they were received with the utmost enthusiasm, commanders and men being fêted and thanked, both at Cape Coast Castle and in England, for their brilliant services. The expedition entered Portsmouth in March 1874, with loud demonstrations of welcome, the Black Watch especially coming in for a large share of popular attention.

Sir Garnet Wolseley had in London and elsewhere a repetition of the extraordinary reception he and his followers had experienced at Cape Coast Castle on their triumphal return from Kumasi.

A civic banquet was given in April by the Lord Mayor of London in the Egyptian Hall, at which nearly three hundred guests sat down, including nearly all the officers of the expedition. Among those present were the Prince of Wales, Prince Arthur, the Duke of Cambridge, and the Duke of Teck, besides a number of members of the Cabinet. But although the bulk of the honours naturally fell to Sir Garnet Wolseley and the senior officers of the expedition, and Wauchope's name scarcely appears in these public demonstrations, his friends in Scotland had their eye upon the young lieutenant who had in a few short months carved out for himself a distinguished reputation, and had added to the laurels of the house of Niddrie. The people of Portobello specially determined to show their appreciation of his gallant services by a public banquet, and though at first the natural modesty of the young soldier shrank from such a recognition of his services, after some persuasion he consented. The banquet took place on the 12th June in the Town Hall. There was a large gathering of the principal inhabitants. Provost Wood presided, and was supported by, among others, Sir James Gardiner Baird, Lord Ventry, and a number of county gentry.