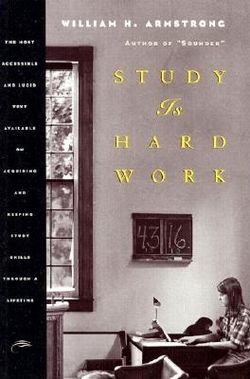

Читать книгу Study Is Hard Work - William H. Armstrong - Страница 6

ОглавлениеForeword to the First Edition

On two matters college teachers, no more given to agreeing with each other than members of most professional groups, regularly express remarkable unanimity of opinion. College students, they agree, are commonly deficient in ability to express themselves well in English and, quite as commonly, deficient in effective habits of work. In some measure, the college teachers’ complaints may be dismissed as the traditional dissatisfaction of the old with the performance of the young. Yet college teachers are not all by nature quick to complain; they welcome skill in expression and diligence in study eagerly enough when they find it and presumably would be glad to find it everywhere. Since they do complain, therefore, their complaints would seem to have some foundation in fact. Often teachers in the schools reply, and quite correctly, that some jobs are never done, learning to write well and to study efficiently among them. And some insist that learning to write and, even more, learning to study are always specific, never general, skills; that is, that successful writing is writing for a purpose, and successful study, study that has a particular end in view. From this postulate they argue that the college must teach writing and skills of study quite as much as the school. In short, to each its own perplexities and solutions.

Like many pedagogical arguments, especially those centering on the development of skills, this one often ends in the slough of despond. Yet in the daily round of life, we all know well enough that we do develop general skills and that we do apply them to particulars much in the way our body absorbs food and distributes it in various chemical forms to all our members. It is manifestly impossible to learn skills anew for each situation we meet; we count ourselves well-educated when we have sufficient command of our faculties to adapt them effectively to new situations as they arise. Such command implies both the development of mental habits and an orientation of the will toward exercise of the mind. It is to that development and that orientation that Mr. Armstrong’s book is directed.

This little book is in many ways an unusual one. To begin with, it has a bluntness far from common in how-to books of any time or dime. Its delightfully perverse title is neither misnomer nor joke. The truth is, and always has been, that formal education (another name for accelerated learning) is hard. “Painful” is the word Aristotle used for it, a term Mr. Armstrong may have in mind when he writes “education without sore muscles is not worth much.” However suspiciously students may look on such a statement as representing the sublimated sadism of their elders, there is solid ground for the observation. Learning something new means altering our stability of the moment. The greater the strangeness or difficulty of the new information, the greater the strain put on our present, and comfortable, state of mind. If we must hurry to assimilate the new—as indeed we must—then we suffer not only from reluctance to disturb our equanimity but from the process of ingestion as well. Studying is hard, and the less students and teachers pretend that it is not, the better.

Mr. Armstrong is not a psychologist, nor does he make any pretense of being one. He is a schoolmaster in the old and half-forgotten sense of that admirable epithet. He obviously knows students, and he obviously knows how to deal with them. His theorizing is of the kind that the young understand and, even as they resist, respect. It deals not with stimulus-response data but with the deep instinct of young people for self-realization, for commitment to an ideal. In fact, for Mr. Armstrong studying is a moral matter first of all, a matter of governing the will—of accepting a right purpose and of concentrating one’s energies toward its achievement.

Today it is a bold man who dares to say that students have a “basic obligation” to work whether or not they are what is called “interested” in the subject-matter. Mr. Armstrong says just that and, in so doing, touches the matter of learning at its vital center. Schooling makes no sense at all unless it assumes that students have a basic obligation to study; and if they recognize that obligation, there need seldom be much need to worry about interest, for interest is the fruit quite as much as it is the stimulus of study.

Archimedes is supposed to have said that, given a lever and a place to stand, he could lift the world. In one way or another, all men spend much of their energy looking for some such external leverage by which to alter or lighten their burdens; and all, like Archimedes, are bound to be disappointed. The job has to be done, in the degree that it can be done at all, from inside. That is the governing principle of Mr. Armstrong’s book: begin with an honest facing of yourself, take honest measure of the work to be done, then go systematically to work.

The student who takes to heart the injunctions and advice of this book should not expect to find all doors magically opening before him. Studying is hard and remains hard; but learning to study well makes the effort pleasant, just as learning to ski well, though skiing. continues to tire the muscles and strain the nerves, makes both sidestepping up a slope and schussing downhill enjoyable experiences. The students who have learned to enjoy study because they know how to do it well are prepared in the best sense of all for work in college and for life. Whatever helps them to learn how to study well is, therefore, an important contribution to their liberal education.

HAROLD C. MARTIN

former Director of General Education Harvard University

As a busily growing animal, I am scatterbrained and entirely lacking in mental application. Having no desire at present to expend my precious energies upon the pursuit of knowledge, I shall not make the slightest attempt to assist you in your attempts to impart it. If you can capture my unwilling attention and goad me by stern measures into the requisite activity, I shall dislike you intensely, but I shall respect you. If you fail, I shall regard you with the contempt you deserve, and probably do my best, in a jolly, high-spirited way, to make your life a hell upon earth. And what could be fairer than that?

IAN HAY, The House Master