Читать книгу Men Who Love Men - William J. Mann - Страница 9

3 ON THE PIER

ОглавлениеEven though the sun has failed to make an appearance today, hiding stubbornly behind a dreary gray haze like a sulky child, Luke wears no shirt, just a backpack slung over one shoulder. A breeze is blowing in off the water, making me shiver, but the boy seems oblivious to it, striding ever closer to where I’m sitting, parading that flat little belly of his, the lines of his damn obliques running down into his loose-fitting cutoff cargo shorts.

Why the hell am I doing this? Why did I agree to meet him when he called? The kid only wants to meet Jeff. Why am I allowing myself to be suckered?

“Hey, handsome,” Luke says, sitting beside me on the bench.

Maybe because of the way his dark blond hair falls in his eyes. Maybe because of the way his lips curl at the corners. Maybe because he called me handsome.

“Hey,” I reply.

“Where’s the sun, dude? I can’t see hiking all the way out to the beach without any sun.” He rustles out a pack of cigarettes from his backpack and shakes out a cancer stick. “Want one?”

“No, thanks, I don’t want to die a gruesome death.”

“Yeah, I know I should quit,” Luke says, lighting up. “Picked up the habit at a young age, and it’s hard to get out of the mindset.”

“It’s called nicotine addiction.” I frown. “And just what is a ‘young age’ for you? Twelve?”

“Close to it.” Luke exhales smoke away from my face. “I was probably thirteen when I started.”

“So how old are you now?”

“Twenty-two.”

Well, what do you know? Seems I’d given him credit for an extra year that he’d never lived. Actually, to look at him, it’s pretty tough to guess his age. He’s definitely got a baby face, and in some ways twenty-two seems too old for him. But in other ways, he seems a bit overripe, a tomato left on the vine a little too long.

“You must have some bad habits,” Luke says, squinting those hazel eyes at me.

“Ice cream.” I pat my belly. “As this squishiness demonstrates.”

“Dude, you’re not that squishy. You need to get over your body hang-ups.”

“Thanks for the advice.”

In my head, I’m keeping a countdown. It’s been nearly two minutes since Luke sat down, and no mention yet of Jeff.

“So, Henry,” the kid says, “you want to get some food later? Maybe you can show me where to eat cheaply in this town.”

I lift my eyebrows. “Not too many cheap options here. At least not if you want to avoid clogged arteries and high blood pressure.”

Listen to me. I sound like my mother. When did I get so old?

“I’m thinking of becoming a vegetarian,” Luke says. “But I figure if I’m going to turn my body into a temple, I gotta quit these things first.” He takes one last, long drag on his cigarette and flicks the butt into the water below. “But that will take some effort.”

“Well, if I can quit the ice cream, you can quit the nicotine.”

“Is that a wager?”

“Oh, I didn’t mean—”

“It’s a deal.” Luke is smiling. “We can check in every day to make sure we’re not cheating.”

I let out a sigh. Overhead a seagull swoops down low, arcing over our heads. I decide to move the conversation away from addictive behaviors.

“Where did you say you were from, Luke?” I ask.

“I’ve lived all over the country.”

I look at him closely. “But in what particular part of it were you born?”

“Long Island, New York.”

Now it’s me who makes a face. “Lung Gyland?” I ask, using the local vernacular. “You sure don’t sound like you’re from Lung Gyland.”

He smirks. “I told you. I’ve lived a lot of places. Besides, not everyone from Long Island sounds like Joey Buttafuoco.”

I can’t help but smile a little. “I guess.”

“My stepdad was a lawyer,” Luke tells me, “so I had a pretty upscale, middle-class childhood. At least for the later part. The beginning of my life is a whole other story.” He pulls his legs up onto the bench to sit cross-legged next to me. Our knees touch. It distracts me from asking a follow-up question and allows him to keep control of the conversation. “So how about you?” Luke asks. “Where were you born?”

I’m very conscious of his knee touching mine. “West Springfield,” I say. “Western Massachusetts.”

He cocks an eye at me. “You sure don’t sound like you come from Massachusetts.”

“Not everyone from Massachusetts sounds like Teddy Kennedy.”

Luke laughs. “And you used to be a hustler?”

I feel my face redden. “Look, it was for a very short period. Before my job at the guesthouse, I worked at an insurance company.”

“So after you punched out, you walked the streets of Boston?”

“No,” I say, surprised at how embarrassed I am remembering that part of my life. It’s never embarrassed me before; in fact, I’ve always been rather proud of it in an odd sort of way—that I’d actually been hot enough to get paid for sex. But now, for whatever reasons, I don’t want to talk about it with Luke. “I had a profile online,” I tell him, trying to find a quick way to end the discussion. “It wasn’t a big deal.” Even though it was.

“I’ve thought about hustling myself,” Luke says, looking down his smooth chest and fingering his navel. “But then I figured, if I’m gonna be a famous writer, I don’t want any skeletons in my past.”

Okay, here it is: the moment when the conversation begins to lead us inexorably to Jeff. I let out a long breath, bracing for it. “And that’s why you moved here,” I say. “To be a writer.”

“Yeah.” Luke’s so natural about it, so confident—as if his dreams will just inevitably come true. “I took a writing class at Nassau Community College and my teacher thought I was a natural-born writer.” He widens his eyes as he looks at me. “I’m not trying to brag, Henry. I’m just telling you the facts. I wrote this short story that not only my teacher but the entire class thought could become a novel.”

“So what’s it about?”

“I’ll tell you over a plate of fried clams.” Luke is standing all of a sudden, adjusting his backpack on his shoulder. “Okay?”

“I’m not really hungry—”

“I am. I haven’t had lunch. And I have a craving for a cigarette—so unless I get some food, I’m gonna smoke. And you agreed to help me quit.”

“I never—”

“Come on, Henry.”

He motions me up.

“Well,” I say, giving in, “we can go over to Mojo’s. It’s quick, it’s cheap, and the food is pretty good, considering it’s a take-out stand. We can sit at the tables in back.”

“Perfect.”

I follow Luke back down the pier. It’s mostly straight tourists out here, women with large butts encased in loud floral print shorts, dragging along husbands who look as if they’d rather be anywhere else. A horde of screaming kids suddenly runs toward us, diverting only at the last possible moment from a collision with my gut. This isn’t the Provincetown of the popular gay imagination. The pier is the flip side of town—where few queers ever venture, except to board the ferry back to Boston. Why I picked this place to meet Luke, I don’t know. It just seemed the best choice—far away from the center of gay P-town. Why that should be important I still haven’t figured out.

In truth, there is no part of Provincetown that is less than beautiful. Even here—even among the tacky T-shirt shops and seashell emporiums—there is a certain exquisiteness to the place. Here, at the end of the earth, even the most ordinary buildings are infused with Provincetown’s particular glow, a result of the sun reflecting off the water all around us. When I first started coming here years ago, Provincetown was just a playground, a place I came with Jeff to take Ecstasy and trick with sexy boys—or attempt to, anyway. I’d dance until two a.m. fuck until five (if I was lucky) and then sleep until noon.

But now Provincetown is home, and my rhythm here is different. I cast my eyes ahead of me, past the colorful kites and Himalayan blankets being hawked in the square. Not far beyond stands the large white nineteenth-century Town Hall, and up on the hill behind it looms the 252-foot Pilgrim Monument. I’m giving Luke a picture postcard view of Provincetown. It’s still sometimes hard to believe that this is my home.

We live here clinging to the last dangling finger of the outstretched arm of Cape Cod, making our lives on a sandy spit that spirals off into the cold Atlantic. No one just “passes through” Provincetown. Only one road leads here, and it ends here, in crumbling asphalt swept over by drifting sand dunes. Here, Thoreau said, you can put all America behind you. The whole world, in fact.

A home at the end of the earth. I remember wondering if it were possible—for anyone other than sea crabs and mussels, that is, or the witless piping plovers forever being chased by the surf. But humans? It’s cold here, and wet, with the bitter winds that blow through here every winter reminding us we sit on just a few square miles of sand in the middle of the sea.

Summers are bliss here. The living—as the song says—is easy. But the winter is a whole other story. New England winters are legendarily tough, but try it out here, with everything boarded up, with the most of the population having headed south to Fort Lauderdale or Miami. Luke has no idea what awaits him. I know I didn’t. Night comes quickly in December, and January, and seemingly even more so in February, despite every logic of the season. “No one passes through Provincetown,” I kept repeating to myself that first winter. The headlights of cars never sliced through my living room. Wayward travelers never stopped me at the gas station to ask where they’d made a wrong turn. Days would go by in my little apartment and I’d see not a single person, or a light in any neighboring window. In those first years, we closed the guesthouse in February and March. Jeff was off on a book tour; Lloyd in a spiritual retreat in upstate New York. I sat out blizzard after blizzard by myself.

At first, I was claustrophobic from the isolation, but that changed. I discovered there was something rather magical about the sea in winter. The way the waves crashed against the hard sand, fierce and brittle, the unrelenting pound of the surf that eats away, bit by bit, year by year, a little more of the land. Looking out at the ocean my first winter in Provincetown, I realized the locals had been right: to say one has lived in Provincetown without experiencing the winter is like saying one has lived in New England without ever once seeing an autumn.

“You’ll get used to it here,” one old timer told me, wearing shorts in a blizzard. “The rules are just a little different.”

Those who live in Provincetown do so purposely. Even without a plan, there is nonetheless purpose. “I just got fed up,” a woman told me last week at the post office, the single point of intersection for many of us. “One day I just quit my job, packed my car, and drove as far as the road went.”

Washashores, the locals call them. I suppose that’s what I am, too, surrounded by writers and painters and people who make little carvings out of driftwood and shells.

But can it be home? Provincetown is a place people come to, not come from. No, that’s wrong: there are still families who’ve been here for generations, descendants of the fishermen of the last century, who cling defensively to their vanishing culture. But the summer population edges fifty thousand; year-round there’s barely three. The old fishing family homesteads are being bought up for exorbitant prices by affluent, mostly gay second-homers who envision Provincetown as the perfect place to retire. They will make it home then, these aging babyboomers, but for now, there’s still no fast food, no giant supermarket, no parking garage, no cinema multiplex, no Kinkos, no Staples, no Home Depot.

Ah, paradise, one might think. And certainly I have no desire to see golden arches looming over Commercial Street. But Luke’s in for a rude awakening when he runs out of printer paper on a late Sunday afternoon. Or tries following a recipe that calls for bok choy in February.

But if home is just convenience, then any strip mall in suburbia could be home. And I suppose it is, to somebody. I’m just glad it’s not me. I’ve come to subversively enjoy the fact that shopkeepers in Provincetown open only when they want to, despite the hours posted on the door. I like that the women in the post office wear outrageous wigs, and that drag queens cash you out at the A&P. Home is a place where you can stand face to face with what’s real in the world, like at the top of a dune, or on a stretch of unspoiled beach.

That’s what comes with making a home at the end of the earth. The rules are different . You don’t meet people passing through because there aren’t any. This is the crossroads of nowhere. This is the end of the road. The people you meet are the people who are here. Some who have dropped out, who have fallen through the cracks. Some who have said the hell with it, and some who have found heaven in a half-mile stretch of sand.

Luke will have to find his own rhythm, discover the town’s secrets for himself. A clerk at the scrimshaw shop once showed me the little shady corner of the town cemetery where on particularly busy days in July he could retreat with his thoughts and his journal. A guy at the Provincetown AIDS Support Group invited me to experience the bleak beauty of Long Point in November. Now I have my own secrets, my own special places.

Working here, living here, I’m not always able to drop what I’m doing when old friends pop in and expect a weekend of revelry. It’s been a very long time since I’ve slept in until noon. I like the sunrise in Provincetown far too much, an event I experienced in the old days only when I staggered home from a trick’s house at dawn. I follow a different rhythm now, but I realize it is the multitude of dances that makes Provincetown so unique. I was once in the same place Luke is in now, wide-eyed as he discovers the magic. And it pleases me to no end that there are still crowds on the steps of Spiritus Pizza at two a.m., still boys sleeping in until noon before stumbling out to Herring Cove beach. I might grumble when the line at the post office extends out the door or when buying a quart of milk at the Grand Union takes an hour and a half, but I’m glad when the boys of summer return. I love the drag queens sashaying down the street, the circuit boys in their spandex, the leather dads and the bear cubs. Each to their own rhythm, their own magic. This is their town as much as mine.

There are those who rue the “commercialization” of Provincetown, who gripe that the place has become too geared to nightclubbing and resort tourism. And yet I remember, soon after arriving here, picking up Time and the Town by Mary Heaton Vorse, published in 1942. Vorse had made Provincetown her home since the days of Eugene O’Neill some three decades earlier, and she was lamenting, “A few people have been allowed to damage the beauty of Provincetown. The rowdy nightclubs, the wholesale selling of worthless knick-knacks, make it possible…to brand the place a ‘honky-tonk.’ Those few who cater to some unwholesome element for a little money rob themselves as well as the whole town.”

Yet Provincetown survived Vorse’s fears, going on to several more “golden ages” after the one she described. Elsewhere, she seemed more optimistic, writing: “The one certainty is that Provincetown is in history’s path as it has always been.” Every season someone new will discover Provincetown and find his or her own rhythm in the place. And so it will go on.

For the boy walking ahead of me—indeed, for all first-timers like him—Provincetown retains its power to bewitch. Here, anything goes. Here one can spot, as Luke and I do now, the fabulous Ellie, a seventy-two-year-young transvestite pulling a sound system in a red wagon down Commercial Street while she croons “My Way” by Frank Sinatra. Watching her, Luke is beaming, pointing her out to me as if I’ve never seen her before—as if Ellie is as new and as fresh as he is. And in that moment, in Luke’s smile, she is. We all are.

At Mojo’s we order fried clams and Diet Cokes and settle in at one of the picnic tables.

“So your novel,” I say.

“Do you really want to hear?”

I smile. “Sure, why not?”

“Well, it’s about this kid, who was homeless, who gets adopted by this really great family but then…”

Luke’s words trail off. He just sits there staring straight ahead.

“But then what?” I ask.

Still he doesn’t say anything. A little voice inside me tells me not to follow Luke’s gaze, not to turn my head and see what he’s seeing. But of course I look anyway.

It’s Jeff, scrutinizing Mojo’s menu a few feet away.

I can’t help but laugh. “Ah,” I say, “if it isn’t your literary idol.”

“Jeffrey O’Brien,” Luke says softly.

“In the flesh,” I say. “What d’ya think?”

“I thought he’d be taller,” Luke says.

I laugh out loud. That one little comment makes my day.

My laughter has drawn Jeff’s attention. He looks over at us.

“Henry,” he says, heading our way. Already I see him checking out Luke. God, do I know that look. It’s the look of a kid in a shopping cart as his mother pushes him down the toy aisle. I want that, his eyes say. But as soon as he’s passed his object of desire, he’s forgotten it and moved on to another.

“Jeff,” I say, accepting the inevitable, “this is Luke. Luke, Jeff.”

“Jeff O’Brien,” Jeff echoes, shaking the kid’s hand.

“I know,” Luke breathes in awe.

“He’s got your book under his bed,” I tell Jeff.

“Actually,” Luke says, unzipping his backpack, “I have it right here.”

Out comes not one book, but three—two in paper, one hardcover.

Jeff beams. “You’ve got the whole Jeffrey O’Brien collection right there. All three of my books.”

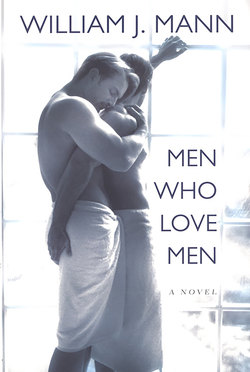

Luke spreads them out on the picnic table in front of us, careful to move the fried clams far away first, so they don’t stain his treasures. There’s the well-read, much-creased copy of The Boys of Summer that I saw under Luke’s bed, plus its sequel, More Boys, More Summer. The hardcover is Jeff’s latest, a more “literary” attempt—one without the prerequisite shirtless boy on the front. Finding Home, it’s called.

“I especially loved this one,” Luke says, tapping the cover of Finding Home. “I thought it was just…I don’t know. Just brilliant.”

Jeff sits down on the other side of the picnic table, facing us. “The critics weren’t so sure,” he says, eyes glued on Luke.

“That’s because they pigeon-holed you. They weren’t ready to let you try something different.”

They couldn’t be playing their parts any better if Jeff had written the goddamn script. I lean my head on my hand, watching this little drama unfold.

“Well, that’s what we like to believe,” Jeff says, in that slightly deeper-than-usual voice he uses around fans. “I’m glad you liked it, though.”

“Oh, man, I loved it.”

I wonder. Finding Home has none of the signs of being well read. Unlike The Boys of Summer, its pages aren’t dog-eared. Its binding isn’t even cracked.

Luke is still gushing. “And I loved the interview you gave to The Advocate about it. You know, where you revealed that you, like the protagonist, were also an old movie and TV fan.”

Jeff twinkles on cue. “You mean the interview where I came out of the closet as a secret geek.”

The boy’s smile threatens to close his eyes with his cheeks. “You are so not a geek. I’m a geek.”

“Well, if so,” Jeff says, “geeks are a lot cuter these days than they used to be.”

I feel my stomach roil, and it’s not the fried clams.

Luke is clearly smitten. He’s rummaging in his backpack again, and produces something I can’t at first identify. It’s flat, and wrapped in plastic.

“Take a look at this,” he’s telling Jeff.

It looks like a small movie poster. Slipped into a plastic bag and backed by a piece of a cardboard, it showcases a woman I don’t recognize. Jeff takes it from Luke’s hands and gazes at it with a kind of wonder.

“Holy shit,” he says. “A lobby card from Becky Sharp!”

“Yeah,” Luke replies, in the same breathless tone of awe.

“Excuse me,” I say, “I hate to interrupt, but who the fuck is Becky Sharp?”

Jeff glares at me. “Becky Sharp just so happens to be the very first feature film made in Technicolor.”

“Yeah,” Luke adds, though he doesn’t look at me, keeping his eyes squarely on Jeff. “And in 1935, starring the amazing Miriam Hopkins.”

“Miriam who?” I ask.

“You wouldn’t understand,” Jeff tells me. “Miriam Hopkins is very big for true film fans, one of the forgotten greats.”

“Well, in fact,” Luke says, reaching into his bag again, “look what else I have.” He pulls out a videotape in a battered cardboard slipcover. “I’ve got one of Miriam’s last appearances—on the TV show The Outer Limits.”

Jeff takes the videotape and inspects it. “The Outer Limits! That was a great show. Sometimes even better than The Twilight Zone.”

“I agree,” says Luke. “Do you know both Geraldine Brooks and Sally Kellerman appeared on it?”

I laugh. “Are they favorites of true film fans, too?”

Luke eyes me. “For true fans, Henry, the people on the screen can sometimes seem like your best friends.”

“But why,” Jeff asks, lifting his eyebrows at Luke, “are you carrying these around in your backpack? You don’t want that lobby card to get damaged.”

“I know,” the boy answers. “But I just don’t feel comfortable leaving it back in my hotel room. If the maid found it…”

Jeff hands the precious relics back to Luke. “You’re staying at an inn?”

Luke nods. “Until I can find a permanent place.”

I notice the smile creep across Jeff’s face. “You’re planning to move here?”

“Yes, so I can…” Luke’s voice trails off.

“So you can what?” Jeff asks.

“Oh, please,” I say to Luke, impatient with this little charade, “just tell him.”

“So I can write.” The boy blushes. “Like I have any business saying that to you.”

Jeff beams. No one on the entire planet is more susceptible to flattery than Jeff O’Brien. It’s impossible to lay it on too thick with him. He just laps it up like a pig eating slops.

“A writer, huh?” Jeff smiles. “Well, Provincetown can be a wonderful muse…”

“So I’ve heard.” Luke carefully returns Becky Sharp to his backpack. “And your novels are a big reason why I’m here.”

“I’m flattered,” Jeff says.

“No, really, I mean it.” Luke returns his eyes to Jeff with a passion that exceeds anything I saw yesterday while we were having sex. “Your work has had such an influence on me. Your words…they’ve changed my life.”

That’s when I stand up, grip the sides of the table, and puke all over both of them. Diet Coke and bits of fried clams rain down on their heads.

Okay, so I imagine that part. But for the moment, anyway, the fantasy allows my stomach to stop lurching.

“That’s awfully sweet of you,” Jeff’s saying. There’s a moment of eye-holding silence that leaves me feeling utterly invisible. Finally Jeff asks, smiling warmly at Luke, “Would you like me to sign your books?”

“Would you?”

“Sure,” Jeff says.

What a guy. So magnanimous.

Luke produces a pen from his backpack. Is there anything he doesn’t keep in there? Jeff opens the first book to its title page, pausing to think before he writes. Then, suddenly, without warning, he reaches down and pulls his T-shirt up over his head, revealing his defined pecs and abs. “Damn,” he says, “it’s so hot out today.”

“It is so not hot out today,” I say, unable to keep quiet.

But I’m ignored. Luke is mesmerized as a shirtless Jeff O’Brien signs his books. What our esteemed author writes, I don’t know, and in truth, I don’t care to know. But Luke reads each inscription in turn, cooing appreciatively, and replacing each book in his backpack. When they’re done with their little playlet, they just sit there, two naked torsos grinning stupidly across the table at each other. The sexual energy between them is so strong it could power a small city.

My mind goes back to a night some five, six years before.

“But I thought he loved me,” the boy from Montreal was saying. What was his name again? Jean-Pierre? Jean-Michel? Something like that. There have been many boys from many different places, beautiful boys who fell in love with Jeff and were crushed to discover his affection for them barely lasted through the week. And most of those boys turned to Henry Weiner for counseling and consolation.

Will it be the same with Luke? Once Jeff is done with him, will he come running back to me? Will I let him?

But as I watch them, I feel the situation is a little different this time. Jeff, for all his smooth skin and still tight abs, is no longer the young buck that he was. He’s not out there in the scene in the way he used to be, partly because he doesn’t have the stamina to stay up all night the way he used to but also because he’s no longer quite the focus the way he was in years past. Back in the day, all eyes in the room would turn to look when Jeff O’Brien walked in. But now, as well preserved as he might be, Jeff has discovered the playing field can never be truly level for him again—not when he’s facing off against a new class of twentysomethings.

Like Luke.

And that’s the other reason this time is different. Luke is no wide eyed kid still green in the ways of gay life, like so many of Jeff’s previous boys have been. Jean-Michel—and Raphael and Eduardo and Anthony—were all refreshingly free of guile. But looking at Luke, I see very clearly that he’s been around the rodeo a couple of times. After all, he’d known to search me out and to sleep with me, all part of his nefarious plan to meet Jeff.

And how well that had worked out, all within a day. I wonder if Luke had spotted Jeff on his way into town? Was that why he’d insisted we leave the pier? Had he know somehow we’d run into Jeff? Even if he hadn’t maneuvered their meeting, the kid had known exactly what to do once his prey showed up. Out came the flattery in generous helpings, topped by that well-timed appearance of Supergirl in her carefully wrapped plastic bag. Luke was good. No question about that. Shrewd. Unlike Jeff’s other boys, this time both sides had their own games to play.

“You know what?” Jeff is asking, breaking the charged silence that pulses between him and Luke. “You ought to stop by my house when you have the time. I’ll show you my entire collection of movie posters.” He lowers his voice into a sexy whisper. “I’ve got one from The Birth of a Nation.”

“No way!” Luke gushes. “From 1915?”

Jeff nods. “Not quite near-mint, but pretty fine.”

“When can I come by and see it?”

“What are you doing right now?”

“Nothing,” Luke says. Then, as if remembering there’s another human being seated next to him, he turns to me. “Except that Henry and I were—”

“Go ahead,” I tell him. “Who am I to keep you from The Birth of a Nation?”

“You’ll come too?” Luke asks.

I make a face. “I’ve already seen Jeff’s movie posters.”

“You sure you guys weren’t doing anything?” Jeff asks me, standing up, apparently forgetting about the lunch he’d been about to order for himself. Or maybe he’s just decided he’s hungry for something other than a grilled chicken sandwich. It seems he might prefer his chicken raw.

“Not to worry,” I assure him. “Luke and I weren’t doing a thing. I’ve actually got to head into town. I’m meeting a friend.”

“Well, come on over around seven,” Jeff tells me, motioning to Luke to follow him. “Elliot and Oscar are in town, and they’re coming for dinner.”

“I’ll try to make it,” I say, staying seated as Luke zips up his bag and hurries around to follow Jeff. “But I can’t promise.”

“Who’re you meeting in town?” Jeff asks.

“Oh…no one you know.”

Luke stops suddenly and looks over his shoulder at me. “Want to hang out again tomorrow, Henry?”

“I’m going out of town,” I tell him.

“Well, I’ll call you.”

I give him a little salute. “Say hello to Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks for me. I think Jeff has them, too.”

“Really? Awesome!”

And then Luke is gone, trotting out after Jeff onto Commercial Street.

I take one last sip of my Diet Coke through my straw, making that sucking sound against the bottom of the paper cup. I pick a few crumbs off the plate in front of me, placing them in my mouth, one by one. A gull lands on a post not far from me, folding in its wings against its body. It stares resolutely at me. I look away.

“If you ask me,” comes a voice to my right, “that guy is a shmuck.”

I glance over. At the next table is a guy I recognize from the gym. A real hottie, in fact, with dark eyes and a closely shaven head, and very round biceps that stand out against his tank top like small grapefruits. I don’t know his name, but apparently he witnessed the entire scene between Jeff, Luke, and me.

“Excuse me?” I ask. “What guy?”

“That Jeff O’Brien.” The hottie nods toward the street. “You came in here with that kid, and he took off with him.”

“Oh,” I say, embarrassed. “It’s not like that.”

“Whatever.” The guy takes a bite of his hamburger. “I shouldn’t say anything. It’s none of my business.”

“No, really, Luke and I—there’s nothing between us. And Jeff’s just taking him back to show him his movie posters.”

The hottie practically spits out his burger. “What, were his etchings in storage?”

I smirk. “It’s really okay.”

He wipes his mouth with his napkin and stands, reaching across his table toward mine and extending his hand. “I’m Gale,” he says.

“Henry,” I say, shaking his hand.

“Seen you at the gym,” Gale says, sitting back down.

“Seen you too.”

Had I ever. This guy has a fucking amazing body. He must do two hundred chin ups and then, for good measure—or maybe just to show off—he flips himself over the bar a few times. And when he does a leg press, I sometimes have to force myself to look away, so hot are those bulging calves.

Yet for such a well-muscled body, it’s a delicate one, too, in a way. Gale can’t be more than five-seven, and his waist is tiny. Twenty-eight, probably. Maybe even twenty-seven. His features are soft and pretty, almost like a girl’s. Not really my type—but there’s no denying this guy is hotness personified.

I don’t know why I feel I need to defend Jeff, but I do. “Jeff is just a natural-born flirt,” I tell Gale. “I’m totally used to it. And that kid…well, I knew all along it was Jeff he wanted to meet.”

Gale shrugs. “I still think it was rude. But it’s none of my business.”

“Jeff’s my best friend,” I go on. “He seems shallow, but he’s not. Please don’t think badly of him. Inside, he’s a sweetheart, and he’d do anything for somebody he cares about. Really.”

“Okay,” Gale says, smiling. “I believe you.”

“Good.” I laugh. “I can’t have people thinking badly of him. I’m going to be the best man at his wedding.”

“At his wedding? And meanwhile he’s taking this twinkie back to his place?”

“It’s…a long story.”

“No, it’s not,” Gale says, shaking his head. “Non-monogamy rules the gay world.”

“Not my gay world,” I tell him.

He arches an eyebrow at me. “Really? Is that true, Henry? Are you really one of those rare believers in monogamy?”

I laugh awkwardly. Why am I talking so much? I don’t even know this guy. But I continue, just the same. Talking, in fact, suddenly feels good. “Well, I believe in it for me, anyway,” I explain. “If other guys can make open relationships work, then good for them. I just never could.”

And never would, I suddenly think, if it were me marrying Lloyd. If Lloyd was my lover, there’s no way I’d be bringing some twinkie in off the street for a quickie.

“Well, Henry, I’m glad to hear it,” Gale is saying. He stands up, carries his tray to the trash, and slides the remains of his lunch into the barrel. Then he turns and walks back over to me. He stands in front of the picnic table where I’m sitting. “In fact,” he says, “hearing that makes me want to ask you out to dinner. How about it?”

I stare up at him, momentarily unable to speak. “Yeah, sure,” I say finally.

“When?” Gale asks.

“Anytime,” I reply, still looking up into his big round brown eyes.

“Well, tomorrow’s no good,” Gale says.

“No?” I ask.

He grins knowingly. “You told the kid you were going out of town.”

I can’t resist smiling myself. “Well, I think my plans might change.”

Gale’s grin broadens. “When will you know for certain?”

“Right now.” I stand, realizing I’m a couple of heads taller than he is. But height hardly matters—not when I’m caught in the gaze of those soft brown eyes. “What time do you want to meet,” I ask, “and where?”

“How about seven-thirty at Café Heaven?”

“Good deal,” I say. We shake. Gale’s hand is small in my own, but his grip is firm and masculine.

“See you tomorrow night then,” he says, heading out.

“Yeah, see you tomorrow night,” I echo.

I watch him hop on his bike and ride away. Those amazing calves flex as he pumps the pedals, and his butt looks pretty damn good, too, as it lifts off the seat.

I carry my own tray to the trash. My eyes find those of the gull, who’s still sitting there staring at me.

“You can go now,” I whisper. “Everything’s done here.”

The bird spreads its wings and flaps away.

I smile to myself, and head home.