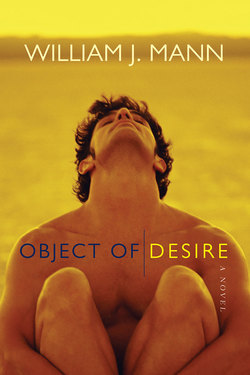

Читать книгу Object of Desire - William J. Mann - Страница 13

PALM SPRINGS

ОглавлениеThe second time I saw him, he was again behind a bar, focused on his work, withholding his eyes from the crowd. For a moment, I could neither speak nor move.

The night was golden, an appropriate hue for this house of affluence set into the mountains, its moveable glass walls obscuring distinctions between interior and exterior. The soft golden glow came from carefully concealed floor lights and artfully recessed ceiling lamps and a crystal chandelier that hung grandly in the marble foyer. From the terraces came the illumination of torches. Everywhere, the night was gold.

And as my beautiful bartender moved behind the bar, the light accentuated the goldness of his skin and left me transfixed.

“Danny?”

Frank was looking around at me, clearly wondering why I had paused in our walk across the room.

“Are you coming?”

“Yes,” I managed to say and, with a soft exhalation, resumed my stroll across Thad Urquhart’s parlor.

“Danny!” Our host had spotted us and was grabbing my hand with both of his. “Danny Fortunato! And to think I didn’t recognize you the other night.”

I smiled. Why would he? Who recognized artists? But, then again, I had a name—a name that people were talking about in this town, a name that was supposed to be new and hip and happening, a name that Disney had thought good enough to hire, that Palm Springs Life had placed on its cover—and in Palm Springs, names meant something. Palm Springs needed people with names to prove it was more than just a weekend getaway for Angelenos or a nude resort town for flaming queens. And so the people with pull in Palm Springs put me on their local radio shows and the local cable access station, and started inviting me to their parties. In the city’s gay rag, my face showed up as a “local artist.” The gallery downtown reported people were making inquiries about my prints, even if no one had bought one yet.

Still, I had a name, however meager, and people with names came to Thad Urquhart’s house.

People with names—and their spouses.

“This is my partner,” I said, gesturing to my side. “Frank Wilson.”

Thad gave Frank a warm, pleasant smile, shook his hand briefly, then immediately returned his eyes to me.

“Is it true,” he asked in a stagy, conspiratorial whisper, “that Bette Midler has commissioned a piece from you?”

“I don’t reveal who’s commissioned my work,” I said, with a smile.

His eyes danced. Of course, he took my reply as confirmation and giggled. Thad looked the same as he had the other night—short, maybe five-five, with immaculately combed white hair, so white and so even, it was obviously dyed and transplanted. His face was pudgy but smooth, laser blasted, I was sure, at regular intervals in the cosmetic surgeon’s chair. He sported a pin-striped, double-breasted charcoal gray blazer and a white shirt without a tie. His large pocket silk was gold, to match the lighting, no doubt. His small hand sported gold and amethyst rings on three fingers.

But I liked him. There was something about Thad Urquhart that seemed comical, ironical, as if he knew all of this was merely a show, and for the night, he was the ringmaster—so why the hell not just have a good time?

Thad was leaning into me, his arm around my shoulder. “Funny,” he said, “for a guy with such an Italian last name, you don’t look very Italian. You’re very fair.”

“Only my father’s father was Italian,” I explained. “His mother was Irish, and so was my mother. A hundred percent.”

“But you don’t look Irish, either.” Thad made a face as he studied my features. “Are you sure you weren’t left on your parents’ doorstep, in a basket?”

We laughed. But the comment touched a nerve somehow.

Thad took my arm and led me out onto the terrace. Frank followed half a step behind. “Let me get you boys something to drink,” our host said.

Of course, it was sheer delight to be called boys at our ages, but in Palm Springs, even for Frank, it wasn’t really so far off the mark. Up ahead of us the crowd was mostly gray haired and over sixty, though among the sea of blazers, a handful of buff boys stood out in their tight white T-shirts. And, as always, there were a few stars from the old days—de rigueur for Palm Springs parties, especially gay Palm Springs parties. Not the really big stars, of course—they were mostly all gone now—but people with names who added a little gloss to the festivities, who cast a little glow of nostalgic recognition. In the last few weeks, I’d seen Anne Jeffreys and Howard Keel and Kaye Ballard. Tonight I noticed Ruta Lee in a red boa. And Wesley Eure, the former star of one of my favorite shows when I was a kid, Land of the Lost, as handsome at fifty as he’d been at twenty.

“What would you like, Danny?” Thad asked me as we approached the bar.

“Vodka martini,” I said, drawing my eyes away from the crowd. “Grey Goose if you have it.”

Thad nodded. “Of course, we have it. With olives?”

“No,” I said. “With a twist.”

“And you?” he asked Frank.

“Just a glass of pinot noir, please.”

The three of us pressed up against the bar. The bartender turned to face us.

Was I hoping he’d remember me? Was there some crazy notion in my head that our fleeting encounter the previous weekend at happy hour might have stayed in his brain? If I was, I was being silly. Schoolgirlish. Our interaction had lasted only a few seconds. I’d ordered, he had gotten my drink wrong, giving me olives instead of a twist, and that had been it. There’d been nothing memorable about the moment. Absolutely nothing.

For him, anyway.

I watched as he approached us. The soft hint of a smile was playing across his full lips. But he smiled because he was looking at our host, the man who had hired him, who no doubt was paying him a pretty penny to bartend this private party. He was not smiling at me. I was under no delusions that he might be.

Thad gave him our order. The bartender listened attentively, nodding, then went swiftly about his work. I noticed the head of his eagle tattoo peeking out from below the neckline of his T-shirt. I had to force myself to look away.

“Now, tell me,” Thad was saying, leaning against the bar and turning to face Frank and me, “where do you live? How long have you been out here in the desert?”

“We live in Deepwell,” I replied. Thad raised his eyebrows and smiled. Deepwell might have been modest compared to the mansions in this part of town, but it was an architecturally rich neighborhood, and Thad seemed to approve. “I’ve been out here now about four years,” I continued, “while Frank’s been here for ten.”

“Ten?” Thad looked wide eyed at my partner. “And we’ve never met before this?”

“Well, we poor college professors don’t often get invited to swanky parties,” Frank said.

I had to smile. Frank always called rich people and rich events “swanky.” It was a great word. He said his mother had always used swanky to describe the movie-star parts of Palm Springs when they’d go sightseeing through the town. “Over there is where Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner live,” Mrs. Wilson used to say, pointing out the house on Alejo. “They give the swankiest parties. I’ve read all about them in Photoplay.”

“Well, it’s about time that changed,” Thad said, giving Frank a warm smile and a clap on the back. “I hope you and Danny visit us often.”

I felt he was being genuine. I glanced up and imagined one of my prints hanging over his bar.

The bartender had returned with our drinks. He placed them on the bar in front of us, and I noticed his hands, the thin line of fine dark hair that crept along the outer edges. I had an overwhelming desire to bend over and lick that line of hair. I actually felt my body moving into position to do so, and I had to stop myself. My heart was suddenly thumping in my chest. As I looked up from his hands, I came into contact with his eyes—those dark mirrors that suggested a kind of glassy madness. But already he was looking away, indifferent to me, if he had even seen me at all.

For a moment, I couldn’t lift my drink. Frank and Thad went on talking, but I just stood there, unable to move or think. My palms were actually wet. What was it about this young man that so compelled me? Of course, I had always loved beauty, been partial to it, easily susceptible to its charms. I had worshipped Scott Wood. And as a teenager, I had clipped photographs of beautiful men from magazines and pasted them in a spiral scrapbook on which, in black Magic Marker, I’d written “Beautiful Men.” That scrapbook had been kept hidden in my drawer so my mother wouldn’t find it—even though I really hadn’t needed to worry, since she’d rarely come into my room after Becky disappeared. My bed had never got made; my floors had never been dusted. So, in fact, my Beautiful Men had been safe in their drawer: Robert Redford and Burt Reynolds and David Cassidy had had little chance of being discovered. Sitting on the edge of my bed, I’d page through that scrapbook, looking at the beautiful men, studying their faces. Then I’d stand in front of my mirror, sometimes for hours at a time on a Sunday afternoon, and compare my features to theirs—because, after all, there was nothing else to do except go downstairs and get dragged into one of Mom’s schemes to find Becky. So I’d stay in my room, in front of my mirror, looking at myself, wondering if I was handsome. I was never sure.

I managed to lift my martini and take a sip. The potency of the alcohol seemed to steady me. I looked around at the men placing their orders. I was sure they found the bartender beautiful, too, yet they were not struck dumb. They went on laughing and talking to their friends. They thanked the bartender and seemed to have no particular urge to connect with his eyes. I couldn’t understand it. Could they not see the classic structure of his face? The way the golden light caught the dimples in his cheeks? The way the muscles of his back moved under his T-shirt? Why weren’t they standing in place, as I was, staring, mouths agape, mute?

“Danny.”

I turned abruptly.

“Thad just thanked you for introducing him to Randall,” Frank said.

“Oh,” I said and managed a smile. “I gather you all had a good time last weekend.”

“We did indeed.” Thad grinned. “It’s not often a couple of sixty-somethings score a young man on a Friday night.”

“I’m sure Randall will appreciate the description.” I glanced around the terrace. “Where is he, anyway?”

“I introduced him to a friend of mine,” Thad said. “I felt it wasn’t fair to keep him just for ourselves.”

I laughed. “How generous of you.”

Thad smiled, then turned his eye to Frank. “So, Professor, I’d like to know where you teach, what you teach, and who you teach.”

Frank took a sip of his wine. “College of the Desert, English literature and composition, and my students are a pretty good mix of college-age kids and older people returning to school.”

“A rewarding vocation, no?” asked Thad.

Frank nodded. “Yes. Usually.”

“My mother was a teacher,” Thad said. “My father died in World War II, and she supported four of us kids on her teacher’s salary. Wasn’t easy.”

I looked around at all the spun glass and marble. So Thad Urquhart hadn’t come from money. Maybe Jimmy had. But I suspected Thad had worked hard for all this, and I respected him more for that.

“Was it a hard adjustment moving out here, Danny?” Thad asked. “Leaving L.A., coming to Palm Springs?”

“Hard?” I shook my head. “I wouldn’t say it was hard. Excruciating, maybe. Horrendous and horrible. That gets closer to it than hard.”

“Oh, Danny,” Frank said, shaking his head.

Thad was laughing. “And why was it so excruciating?”

“Well, I was thirty-six. Practically everybody else out here was retired. All my friends were in L.A., and I missed the social life I had there.” I smiled. “But it was important that Frank and I be together full time again.”

We exchanged a look. Frank gave me a small smile in return.

“But now you love it?” Thad asked. “Tell me you love it now.”

“I love parts of it.” I took a sip of the vodka. It felt good going down, its magic spreading through my body, from my throat to my chest to my shoulders and down my arms to my fingertips. “I love the mountains. I love the feeling I get looking at them, being surrounded by them. I love hiking up to the peaks, exploring the canyons. And I love our house and our yard. I create really well out here. I’ve been far more productive out here than I ever was in L.A. And you sure can’t beat the weather—except maybe now, in the summer.”

“But at night…” Thad gestured around him. “These cool desert nights…”

I laughed. “It’s still ninety degrees at nine o’clock. That hardly counts as cool.”

“But it’s dry. Dry heat. Muggy summer nights back East are far worse,” Thad noted.

I conceded the point there. As a kid in Connecticut, I’d spent many a hot, humid night spread eagle on my bed, nothing covering me, not even a sheet, a big electric fan pointed directly at me. We never had air-conditioning. I’d lie there, facing the ceiling, tongue out, listening to my mother bang around in the kitchen downstairs at two thirty in the morning. After Becky disappeared, Mom never slept a full night through. She slept in odd patches of the day, like from ten to eleven in the morning and again from five to six in the afternoon, usually on the living-room couch. She rarely made dinner after Becky disappeared. Dad would bring home buckets of chicken from KFC or double cheeseburgers with extra fries from Wendy’s. How I remained skinny as a beanpole, I’ll never understand.

“But what parts of Palm Springs don’t you like, Danny?” Thad was asking. “You’ve described all its natural wonders. What about when you move indoors?”

I made a face. I didn’t know this man well enough to say what I really felt. Frank called me judgmental, and maybe I was. Yet parties like this one recycled the same fifty or so people, the same faces that appeared, issue after issue, in the local gay rag. There was the local radio “personality” who carried fake Louis Vuitton bags and billed herself as a Hollywood actress (she’d made a few commercials in the 1960s). There was the local impresario who produced bad—very bad—musical theater, starring such Love Boat veterans as Mary Ann Mobley and Ken Berry. There was the self-help guru who self-published her own books and then self-printed promotional postcards declaring they were “critically acclaimed.” Yes, if we counted all the self-reviews.

And all that was needed to get a good cross-section of the gay population here was to sign on to ManHunt or Adam4Adam. Very few GoodLookingRedheads or TallNiceGuys. Eighty percent of the Palm Springs profiles had names like CumEatMyMeat or DumpYrLoadNMe. One drive through the Warm Sands area at 2:00 a.m. was enough to catch dozens of crystal-meth heads sniffing around for sex like mangy dogs hunting through a trash heap for a meal.

“You’re being judgmental.”

I snapped my head toward Frank. He hadn’t actually said the words, but I’d heard them just the same. He was looking at me as Thad awaited my answer.

I smiled. “Let’s just say I haven’t made many friends here. Most of my friends come in from L.A. on the weekends, like Randall.”

Thad put his hand on my shoulder. “Well, I hope that will change. I hope you and Frank will come back soon to have dinner with Jimmy and me.”

“We’d like that,” Frank said.

I lifted my glass, and we all clinked.

“And you must let me look at your portfolio,” Thad said, a little grin playing with his lips. “Don’t you think a Danny Fortunato print would look good over the bar?”

“Hmm, now that you say it…” I smiled, but I dared not turn around to look where Thad was gesturing. I might see the bartender again, and I didn’t think I could bear it.

It was at that moment that I spotted Randall. He was approaching us, waving his hands like an excited teenage girl. I wondered if the man accompanying him might be the cause of his excitement.

“I was wondering when you’d get here,” Randall said, bestowing kisses all around. “Doesn’t Thad have a marvelous house?”

I nodded in agreement. My eyes were fixed on the man with him, a dark, well-muscled man of Middle Eastern background, with a short-clipped beard.

“Hassan,” Thad was saying, “these are two new friends of mine. Danny Fortunato is an artist, and Frank Wilson is a professor of English.”

“I am pleased to meet you,” Hassan said, with an accent I couldn’t quite place. He shook Frank’s hand, then mine.

“Hassan is a photographer,” Randall told us, and I could see that he was smitten. “That’s his work on the wall over there.”

“Yes,” Thad said, gesturing across the room to a large black-and-white photograph of a naked man, only half visible, against a stark concrete wall. “It’s a self-portrait. Taken in Baghdad before the fall of Saddam.”

“Are you Iraqi?” Frank asked.

Hassan nodded. “I was born in Basra and lived many years in Baghdad. My family was not religious, and we did well for a time.” He smiled tightly. “For a time.”

“Hassan was explaining to me that he doesn’t take portraits of people to flatter them,” Randall said. “He looks at a person and sees the quality that most defines them, and he takes a picture of that.”

“Oh?” I looked over at the photo on the wall. Hassan had a beautiful body, and he had photographed himself quite provocatively. “And what quality is captured in that picture, might I ask?”

Hassan turned his dark eyes to me. “Faith,” he said simply.

“Faith? But I thought you said you weren’t religious.”

“Faith need not be about religion,” he said. “It is faith that has defined me from infancy. Faith in my own destiny, faith that I would go where I needed to go. That I would make it from there to here.”

“Fascinating, isn’t it?” Randall gushed.

Smitten indeed.

“Go ahead,” Randall was saying, nudging Hassan. “Tell them what you see when you look at me. The quality you say defines me.”

“Hope,” Hassan said plainly.

I sneered. “Clearly, you’ve just met.”

The photographer’s eyes hardened. “It is when I just meet a person that I see most clearly.”

Randall smirked. “My very good and dear friend Danny is being sarcastic, because I’ve been a bit, well, pessimistic of late.”

“That doesn’t mean you are not hopeful at your core.” Hassan looked from Randall back to me. “At his core, would you say he was hopeful?”

My mind flashed back many years. A night at Randall’s house in West Hollywood. A horrible night. It was raining miserably, and there was a leak in the ceiling, and water was pooling in the kitchen. And Randall sat on his couch, his eyes unblinking. “Positive,” he said over and over again. “The test came back positive.”

“What are we going to do?” I asked, the “we” uttered by instinct. I was terrified.

Randall didn’t answer right away, but finally he just shrugged. “Just go on living,” he said. “I guess we just go on living.”

Just go on living.

“Yeah,” I admitted to Hassan. “Hope is a good word for Randall.”

“And me?” Frank ventured. “If you were to take a picture of me, what would you be photographing?”

Hassan turned to face him. “Gravity,” he said, without a pause.

“Gravity?” I asked.

“Yes. Do you disagree?”

Frank was looking at me.

“No,” I said. “Once again, you’ve hit the nail on its head.” I smiled. “Just don’t do me, okay? I don’t think I want to know.”

“Well,” Thad said, “I’m sure it would be talent or beauty or artistry or something like that.” He was such a good host. “Now, my friends, I must go and mingle. Do enjoy yourselves. Wander around anywhere you like. Have as much to drink as you like. Enjoy this beautiful desert night.”

We all nodded as he moved off into the crowd, embracing and kissing the next group of people. The four of us stood awkwardly for a moment.

“Oh, go ahead,” I finally said. “Tell me what you see in me, Hassan.”

He hesitated. “No, I think when someone is reluctant, it’s best not to.”

Now I was curious. “No, really. Go ahead. I was just kidding.”

“Yeah,” Randall said. “What do you see in Danny?”

Frank looked at me uncomfortably over his wineglass as the photographer trained his gaze on me. This time there was no quick pronouncement. He started to say something, then stopped.

“What is it?” I asked. “I feel like I’m with a fortune-teller who doesn’t want to give me bad news.”

“I don’t see anything,” Hassan said finally.

I smiled. “So finally someone has stumped you, huh?”

Hassan shook his head. “No. I mean I see nothing. If I took a picture of you, I would be taking a picture of emptiness.”

I had no reply to that.

“Well,” Frank said, moving in to defend me, placing his arm around my shoulders, “you’re wrong about that, Hassan. Danny is hardly empty. He has tremendous passion and great talent—”

“I am sure that he does,” Hassan said. “I did not mean to offend. But you asked me what I saw. And when I look at you, my friend, I see a great aching emptiness. Something that is missing. Something that you are always looking for but have never found. If I took a picture of you, that is what would come through on the image.”

“Well,” I said, trying to lighten the mood, “then maybe I ought to stick to getting my shots done at Olan Mills.”

We all smiled.

“Please,” Hassan said, “you will not take offense at my words?”

“No,” I assured him. “No offense.”

But I lied.

I wanted to get away from them. From all of them. From this entire party of powdered and perfumed peacocks. Friends in Los Angeles had told me I’d never make it big, really big, as an artist until I learned to schmooze. But I hated schmoozing. Hated smiling at people I didn’t know, making small talk with people I didn’t want to talk with, being charming to a room full of phonies when all I really wanted to do was hang out at home, on my couch, the remote control in my hand, flipping back and forth between reruns of Doctor Who and the E! True Hollywood Story.

But smile I did, and small talk I did engage in, as we moved in and among the crowd, getting kissed by Ruta Lee and clucked over by queens. I did my best. At least forty percent of the assemblage would leave that night with my card in their pockets. As Thad dragged me from one of his friends to another, I kept smiling and shaking hands, popping breath mints repeatedly into my mouth. Soon enough, I needed another drink, and Jimmy, Thad’s less gregarious lover, was dispatched for a refill. I was glad for that, not wanting to approach the bar again myself.

And then, midway through the night, a murmur rippled through the crowd. Donovan and Penelope Sue Hunt had arrived at the front door. Everyone stopped their conversations, whipped their eyes away from their companions, and turned to see.

“Well,” Randall purred in my ear, “if it ain’t your old boyfriend.”

“Donovan,” I breathed.

Long before he’d married Penelope Sue, Donovan had carried the torch for me. He was so rich that labels like gay or straight were simply nuisances. Absurd categorizations. Someone as wealthy as Donovan Hunt didn’t need to declare one way or the other—though, given the number of beautiful boys he always had on his payroll, his preferences were obvious to everyone. Penelope Sue, at least a decade older than her husband, didn’t seem to care one way or another, provided he was on her arm at every function. Tonight she looked her usual shining self, with her big copper hair piled up on top of her head and bright pink lipstick smeared across her face as bold as Joan Crawford had ever worn, outlining and emphasizing her collagen-injected lips. Donovan, at her side, was as tall and handsome as ever, not a fleck of gray at his temples, his cheeks flushed with Juvéderm, wearing a shiny black Prada suit and enormous green Versace sunglasses.

“What’s with the shades?” I whispered to Randall.

He looked at me mischievously. “You mean you haven’t heard what happened to Donovan?”

I shook my head. Truth was, I didn’t care what happened to Donovan Hunt, even if everyone else seemed to live vicariously through him. Even at forty-five, Donovan remained the golden boy of the desert, a Peter Pan who refused to grow up, whose toys included a Jaguar; a Bentley; a private jet; homes in the desert, Maui, Highland Park (an exclusive suburb of Dallas), and Nantucket. Some of those homes Penelope Sue shared. Others she most decidedly did not.

“One of his boys beat him up,” Randall told me, almost mirthfully. “Stole a bunch of money and credit cards. Donovan had to go to the premiere of his latest picture wearing makeup and dark glasses to hide the bruises.” He gave me a look. “Or so I was told.” He snickered. “Guess they’re not all healed yet.”

Thad and Jimmy and a gaggle of others had hurried to embrace the newcomers, bestowing kisses and uttering exclamations of undying love. A few in the crowd around us had returned to their conversations, but most eyes remained fixed on the spectacle that was Penelope Sue and Donovan.

“Which boy did this dastardly deed?” I asked Randall.

“Not sure. I know it wasn’t the boy from New York.”

“Then it was the Mexican boy,” I said.

Randall shook his head. “Oh, no, not Victor. He’s a sweetie! He’d never do such a thing. I think this was a new boy, one that none of us had ever met.”

I sighed. I was tired of trying to keep track of Donovan’s boys. The topic bored me—or rather, I wanted it to bore me. But the truth was, I was dying to hear about Donovan being beaten up. In detail.

Randall didn’t have much to tell, however. “I just heard that he got beaten up right before the premiere, and he wouldn’t take off his sunglasses, even in the theater.”

“Now, boys,” Frank scolded us, easing in. “Don’t be so gleeful.”

“Gleeful?” I asked. “About Donovan getting beaten up? Us?”

“Say what you want about Donovan, but he’s made some good movies in the last couple of years,” Frank said. “He’s using that money he made in the eighties for good purpose now. Few studios would commit to making films like he does. I read a fantastic review of this latest one a few days ago in the Times. No matter what you think about him, Donovan really gets behind some worthwhile filmmakers.”

I grunted. I knew I was being unfair to Donovan. He really wasn’t so bad, and it was true that he was making some good, gay-positive films. I guess he’d made so much money from Bruce and Chuck that he had no idea what to spend it on. Once, years ago, he’d offered to spend it on me. He’d told me if I left Frank, he’d make me a star. He’d finance a movie that I could both star in and direct. It was quite the offer, and I believed he was serious. After all, he’d argued, Frank was going nowhere, but he, Donovan Hunt—one of the biggest independent producers in Hollywood—could do anything he wanted, including make a movie star out of a failed kid from East Hartford, Connecticut. I thought about it overnight, lying there beside Frank, listening to him snore. The next day I went to Donovan and said no thanks.

But our paths continued to cross, especially after Donovan married Penelope Sue and bought a huge estate in nearby Rancho Mirage. Frank and I got invited to every party he threw, with Randall often tagging along. And yet in all that time, his wife had barely spoken three words to me. Even now, I doubted she would recognize me on the street.

“Donovan’s last party was pretty fabulous, you have to admit that,” Randall was saying, both of us still watching him as he crossed the parlor with Penelope Sue to the bar. “I mean, come on, the champagne fountain. The prime rib. The bubble-butted waiters wearing aprons and nothing else…”

I turned on him sharply. “Don’t forget that was the party where you met Ike.”

That shut Randall up. He frowned and went off in search of Hassan.

Suddenly Thad Urquhart was at my elbow. “Danny,” he was saying, “I want to introduce you to two very important people.”

Before I had a chance to say anything, he had my forearm in a firm grip. I turned to Frank for help, but he just smiled and held up his hands. “Tell them I said hello,” he said, winking. “I’ve got to make a visit to the boys’ room.”

“Thanks a lot,” I grumbled as Thad tugged me toward the bar.

Penelope Sue was sipping a glass of white wine as we approached her. Donovan wasn’t drinking. Thad practically pushed me in front of them. “Darlings,” he said, “you have to meet my latest discovery, Danny For—”

He was quickly cut off by Donovan. “No need to sing the praises of Danny Fortunato to me, Thaddeus,” he said. “I’ve been singing them myself for more than a decade.” He bent forward to embrace me. “How are you, angel puss?”

“Just ducky,” I told him. “What’s with the glasses?”

“An eye infection,” he said blithely. “Penelope, have you ever seen Danny’s art? You need to commission a few pieces.”

She smiled. Nothing more. No extended hand, no hello. But I was treated to the sight of that thick, broadly painted pink lipstick curling upward. Not everyone got that much from Penelope Sue. Then she turned to greet someone else.

Donovan was moving away himself, another set of hands eager to touch his shoulder or his arm, hoping some of his wealth and privilege might rub off. But before he was gone completely, he turned back to me. “Danny,” he said, “you and Frank must come next week to Cinémas Palme d’Or. It’s the desert premiere of my movie, and there’s a party afterward at the Parker. You must come!”

I nodded. He smiled, blew a kiss, and was gone.

“So you know Donovan Hunt,” Thad said.

“An old friend,” I replied dryly.

His eyebrows lifted knowingly. “A small world, isn’t it?”

“When you’re gay, very small,” I said. “Not that I’m saying Donovan is gay…”

Thad laughed. “I’d imagine a boy as good-looking as you must have gotten to know quite a few people on your way up.”

It was my turn to laugh. “There’s one person I don’t know, Thad, and I was hoping maybe you could help me with that.”

“Of course,” he said. “Who do you want to meet next?”

“I’m not sure I want to meet him,” I said. “Maybe just know his name.”

Thad looked at me strangely.

“Your bartender,” I said.

A smile slowly stretched across his face. “Ah yes,” he said. “Kelly.”

“Kelly?”

Thad nodded. “A sweet boy but—”

“But what?”

He laughed. “No buts. He’s a sweet boy.”

Our eyes moved over to watch him behind the bar. He was shaking a martini, the muscles in his lean arms taut.

“I noticed him at happy hour last Friday night,” I said.

“Oh, you won’t anymore,” Thad told me, shaking his head. “He was fired. So he was quite appreciative when I hired him to bartend here tonight.”

“Why was he fired?”

Thad winked. “He tossed one drink too many into a customer’s face. You see, the boy has a bit of a temper.”

“And what did the customer do to get a drink in his face?”

“Who knows? But whatever it was, Kelly took offense.”

I looked back at the bartender. He was handing the martini over to a man who was leaning in to say something. I couldn’t hear what was said, of course, but I knew the gist. It was a pickup line, a come-on. The man’s face looked as if he considered himself very clever, and no doubt he thought what he’d said was funny and provocative. He probably thought it was something that Kelly hadn’t heard before, that he’d found the magic word that would entice the boy into his bed. I laughed to myself. No wonder drinks had been tossed in customers’ faces. Kelly was no doubt hit on all the time, always being treated like an object for the amusement of old men’s libidos. I remembered that feeling, standing on my box in my yellow thong. I had liked it at first, gotten off on the rush. But it had got old quickly, and by the end I had come to despise the men waving their cash, who thought a Benjamin could buy their way into my life. To this latest idiot, Kelly didn’t respond, didn’t so much as raise an eyebrow or crack a smile. He just moved on to the next person in line, leaving the humiliated man to slink away back into the crowd.

“I’ll bet,” I said, turning to Thad, “that the recipients of the drinks in the faces deserved every drop they got.”

“Perhaps,” Thad said, coming in close, “but I’d suggest, my dear Danny, that you use extreme caution when dealing with this particular boy. Oh, sure, he’s pretty to look at and endearingly sweet on first encounter, but beyond that beguiling surface, there is something not quite right.”

I said nothing, just gave him a slight nod. I’d let him think I was taking his advice, at least for the time being. I wanted the conversation to end, and that was the best way to achieve my goal. Thad winked at me, then moved back among his guests.

I leaned against the wall and trained my eyes on the bartender. Kelly. That was his name. Not a name I would have expected for him. In my mind, he was a Rick or a Tony or a Brad. But now I couldn’t imagine any other name for him. Kelly. As I watched him, I repeated his name in my mind. Kelly. Kelly. Kelly.

I recalled Thad’s warning to Randall about that insipid little Jake Jones. I suspected that Thad Urquhart, no matter how much I had started to like him, was a fussy old man made nervous by the unpredictability of youth. Instead of exhilarating, he found it disquieting. Instead of wondrous, worrisome. But what he feared, I longed for. Suddenly I realized how much I craved the very volatility that Thad dreaded. Suddenly I was on fire for someone to take my staid, stale routine and turn it around, stand it on its head, shake it up the way Kelly shook his martinis.

I wanted him.

I stood there against the wall and watched him for some time, desiring him more and more with each passing minute, oblivious to everyone in the room but him. Finally—maybe after an hour, or even more—Frank found me and asked me if I was ready to go home. I wasn’t, not by a long shot. But I said I was.

That night in bed, I touched a hot hand to Frank’s cold leg, made that way by bad circulation. He did not stir. Of course, he’d fallen soundly asleep as soon as the light was switched off, just as he always did. But I lay there wide awake for a very long time, staring up at the ceiling, just as I had on so many nights when I was a boy.