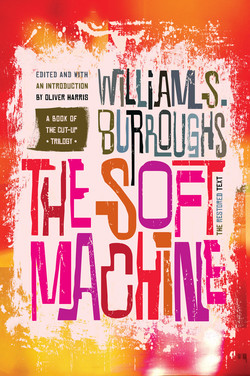

Читать книгу The Soft Machine - William S. Burroughs - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

SOLA ESPERANZA DEL MUNDO

“THIS BAD PLACE, MEESTER”

One of The Soft Machine’s recurrent characters is The Guide, modeled after the local young hustlers who picked William Burroughs up as he explored the jungles of South America in the early 1950s, and any reader entering the book’s alien territory would take the advice of a guide: “This bad place Meester. You crazy or something walk around alone?” The Soft Machine is not only a bad place, it’s an impossible one that mutates before your very eyes: “This bad place you write, Meester. You win something like jelly fish.” In this uniquely queer textual zone styles and genres switch in mid-sentence and incompatible realities mix in a single phrase. “Rubbed Moscow up me with a corkscrew motion of his limestones”? “orgasm crackled with electric afternoon”? “Zero eaten by crab”? Is this science fiction or avant-garde poetry? Drug literature or homosexual pornography? Political satire? All, and yet none of the above, because no labels stick and it doesn’t matter how often you read the text, it will seem new every time. As Joan Didion said, to imagine you can put The Soft Machine down when the phone rings and find your place a few minutes later “is sheer bravura.”1

Not knowing where we are or where we’re going is the disorientating and yet desired experience, so anyone looking for a guide to reading The Soft Machine had better follow the perverse example set by Burroughs himself back in 1953, when solicited by a smiling Colombian street boy: “He looked like the most inefficient guide in the Upper Amazon but I said, ‘Yes.’”2 An efficient guide would only have taken Burroughs where he already knew to go, so following his desire by falling for a hustler was the right choice for someone committed to the difficult path of discovering the unknown. You crazy or something read The Soft Machine alone? Yes, indeed; but that’s the best way to do it because what you find there will be your business. Since the text itself resists mapping, all this Introduction can promise, therefore, is a map of where we are right now, offering for the first time the material history of a book about which so much has remained untold—even the origins of its title, a suitably paradoxical phrase that begins with an utterly misleading definite article, since the book in your hand is not The but A Soft Machine.

“I WISH TO MAKE MYSELF AS CLEAR

AS POSSIBLE”

The Soft Machine is usually described as the first novel in the Cut-Up Trilogy—a straightforward enough place to begin, and yet more false than true. For in the 1960s Burroughs published no less than three entirely distinct versions, so that there is quite literally a trilogy of just Soft Machines and to talk about the book always demands specifying which book. Produced by three different publishers in three different countries, the three editions hold three different positions in three different trilogies, marking a beginning, middle, and end: the first edition of The Soft Machine published in June 1961 by the Olympia Press in Paris—never reprinted, a collector’s item nowadays—was indeed the first book, preceding The Ticket That Exploded in 1962 and Nova Express in 1964; the revised second edition of The Soft Machine published in March 1966 by Grove Press in New York—the only text most readers know—can be placed second, since it followed Nova Express in 1964 and came before Grove’s revised edition of The Ticket That Exploded in 1967; and the third edition of The Soft Machine published in July 1968 by John Calder in London—kept in print in the UK—was the final version of any title and so claims third place. Preposterously, there have been enough Soft Machines for a trilogy of trilogies, and the textual history of Burroughs’ book has been almost as baffling as anything between its covers. Clearing a path through that bibliographical jungle is one aim of this new, fourth edition.

Like most remakes or sequels, as Burroughs produced new editions of the title it could be said he ended up losing the plot, and that despite the brilliance of some of its new material, the second edition is structurally a mess, the third even more so. While that’s true, it again misses the point. The original Soft Machine was the most extreme of all Burroughs’ cut-up books, the most uncompromising, but his revisions over time were not merely a series of compromises or mistakes since the “original” was itself a messy hybrid of materials, impossible to read in any conventional sense. There was therefore no plot to lose, only experiments to try again, and again. Equally, while the history of publication is confusing, it’s the mere tip of a huge archival iceberg that reveals both the messiness and the great care in Burroughs’ working practices. Instinctively as much as ideologically, contradiction was part of his method: when Burroughs cut up his writing he introduced the magical chance factor, an experimental random element, and his writing desk resembled a Ouija board in a science lab; whereas when he edited the results, he could be as rigorous as the most traditional nineteenth-century novelist.

But while they’re always called “cut-up novels,” the term tells us very little: how much is “cut-up” and how much is a “novel”? How does The Soft Machine differ from Nova Express or The Ticket That Exploded? How do the three editions of The Soft Machine differ from each other, when were the changes made, and why did Burroughs make them? To answer the first questions and clear up some of the myths about the last one, a precise history is difficult but necessary and long overdue. As well as narrating The Soft Machine’s perplexing story, this introduction explains why an archival manuscript from 1962 with a unique place in that history has been used to make further restorations and revisions for this fourth edition. More precise details of texts and manuscripts are given in the Notes section, supplemented by appendices that include material from the first and third editions as a gesture towards the multiple textual identities of Burroughs’ Soft Machines.

As for the book’s title—an oxymoron which evokes the Pop Art “soft sculptures” of Claes Oldenburg and that directly inspired a series of other Soft Machines, from the 1960s psychedelic rock band to a 1980s analysis of “cybernetic fiction” and a 21st century study of nanotechnology—the received wisdom is that “the soft machine is the human body.”3 In other words, the phrase sums up Burroughs’ urgent warning against genetic and cultural determinism, his bleak vision that we’re automata manipulated by inner and outer forces, from sexual desires to media brainwashing. The received wisdom comes from Burroughs himself but is misleading nonetheless. Significantly, he offered this definition at the very last possible opportunity, in an Appendix added to the third edition of The Soft Machine: the two previous editions not only lacked a definition, astonishingly they never used the phrase “soft machine” except in their titles. But Burroughs didn’t come up with a meaning just for the 1968 edition; even before choosing it as the title for his book, he had already made the term central to the political scenario of his trilogy’s Nova Conspiracy. Burroughs withheld any clear meaning and, as the manuscript draft of his Appendix to the third edition reveals, in the end he defined the term out of sheer frustration: “I have been accused of being unintelligible. At this point I wish to make myself as clear as possible.”4 By “this point”—December 1965, when he wrote the Appendix—Burroughs had been working on The Soft Machine for over six years, and from the origins of the first edition in summer 1959, making himself clear was always the issue.

“I HAVE BECOME A MEGALOMANIAC”

It was in the very week Naked Lunch appeared that Burroughs first referred to writing the book that would be published two years later as The Soft Machine. Having moved from Tangier to the so-called Beat Hotel in Paris eighteen months earlier, Burroughs already had a shadowy, underground notoriety and a fame-by-association through the media attention given the Beat Generation. He would soon share with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac sensationalized treatment in Life magazine, followed by a series of outraged and hostile book reviews. But he was still unknown in July 1959 when Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, seeking to exploit the censorship controversy provoked by the appearance of episodes in a little magazine, rushed out The Naked Lunch in Paris (the definite article was dropped for the American edition in 1962). It was in this context that Burroughs mailed Ginsberg a “sample beginning of sequel to Naked Lunch,” and framed his new writing in the most dramatic terms (Letters, 420).5

“Complete power and confidence has broken through,” Burroughs declared, announcing that after years of failure he had “become a megalomaniac” and was making “incredible discoveries in the line of psychic exploration”: “What I am putting down on paper now is literally what is happening to me as I move forward,” he wrote, insisting it was “no land of the imagination” but real and “dangerous in a most literal sense” (420). Burroughs had been through messianic periods before—in 1956 mocking himself as “Pop Lee Your Friendly Prophet”—and would do again—“the time to be messianic is now,” he declared a decade later, in absolute earnest this time, just after publication of his final edition of The Soft Machine (ROW, 286).6 He was serious too in July 1959, when the impact of living and working alongside Brion Gysin encouraged in him the self-belief for a mission to discover the unknown through his “sequel to Naked Lunch”: “I don’t know where it is going or what will happen. It is straight exploration like Gysin’s paintings, to which it is intimately connected” (Letters, 420). Such total conviction was what he needed in early October when Gysin showed Burroughs the first accidental slicings of newspapers he had made while cutting a mount for a drawing with his Stanley knife. Gysin’s knife fell into waiting hands, and led to Burroughs’ decade-long commitment to cut-up experiments in multiple media from film to photography, scrapbooks to tape recorders. More immediately, the question prompted by the origins of The Soft Machine is what “straight exploration” meant in the context of writing a “sequel.”

“EXPLODED LUNCH”

Over the next eighteen months Burroughs tried out three alternative titles and the content of his new work changed considerably, but he kept referring to it as a sequel to Naked Lunch. The connection was spelled out in the unimaginative first title he considered in September 1959: “Maybe Naked Free Lunch” (Letters, 427). That month he confirmed the material connection between the two books, asking Ginsberg to look for manuscripts not used in the recently-published Naked Lunch “on mythical South American places featuring Carl” and “Scandinavian (Trak) material” (425). This particular material, which indeed ended up in The Soft Machine, dated back two years and was written after and quite separately from “Interzone,” the manuscript completed in June 1957 that was the basis for three quarters of Naked Lunch. Such precision helps move beyond the long-circulated but always vague standard version, according to which the Cut-Up Trilogy was drawn from a “thousand page” Naked Lunch “Word Hoard.”

What was the “Word Hoard”? A mixture of mythology and confusion (even in its title, sometimes given as “Word Horde” or, as if it referred to an actual book, Word Hoard). Kerouac and Ginsberg used the phrase in spring 1957 when retyping Burroughs’ mass of rough manuscripts in Tangier, and it appears a couple of times in Naked Lunch. But Burroughs himself used the phrase only briefly as an alternative for “Word,” the 60-page final section of his 200-page “Interzone” manuscript. A good deal of his “sequel to Naked Lunch” did come out of what he wrote between fall 1957 and fall 1959, but that material has a separate history to the loose “thousand page” myth. The mythology matters because it has had the effect of mixing up the chronologies of writing and blurring distinctions between books. Burroughs even made a gag out of the confusion of his trilogy, referring in the second edition of The Soft Machine to one “novel I hadn’t written called The Soft Ticket” and another called “Expense Account” that in draft was originally titled “Exploded Lunch”—which begs the question; if the myth was so confusing and if the result has been a historiographic nightmare, why did Burroughs himself promote it?

It was more than convenience, having an easy answer on tap for interviewers, and not entirely a philosophical position, a decision to refute fixed identities and epistemological certainty. There were also strategic reasons why Burroughs promoted the connection between Naked Lunch and The Soft Machine, and then Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded. He worked on the cut-up books while helping Grove Press release an American edition of Naked Lunch, well aware of the censorship battle to be fought, and he recognized the publishing advantages of a common approach, especially involving Nova Express. That was why in the January 1962 issue of Evergreen Review, the house magazine of Grove Press, he prefaced early episodes of Novia Express (as it was then titled) with “Introduction to Naked Lunch The Soft Machine Novia Express”—making a trilogy out of those three titles. The following year Burroughs created another surprising trilogy in Dead Fingers Talk, a book made out of sections from Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine, and The Ticket That Exploded. Before it became the first of the Cut-Up Trilogy, The Soft Machine therefore appeared as the middle volume of two different trilogies starting from Naked Lunch.

Burroughs’ position was self-contradictory, however. On the one hand, he promoted cut-up methods as a radical cut in literary history, the literally cutting edge of a new revolutionary movement, most visibly in his two collaborative 1960 manifesto pamphlets, Minutes to Go (with Gysin, Sinclair Beiles and Gregory Corso) and The Exterminator (with Gysin). On the other hand, he also wanted to present his work in terms of a continuous narrative, in which Naked Lunch was a prequel and The Soft Machine a sequel.

Writing in July 1960 to Irving Rosenthal, as he prepared the American edition of Naked Lunch, Burroughs stated that “little of the old material” would be used for his new book because it was now “understanding out of date.”7 While he used much more than just a “little,” almost all the material he did use went only into The Soft Machine, and Burroughs brought Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded into the orbit of Naked Lunch despite the fact that—contrary to the “Word Hoard” myth—their manuscript connections are actually negligible. If Burroughs was being strategic in connecting his books, this applied not only for publishers or interviewers but also in private. In a late 1966 letter he made probably his most emphatic statement on the trilogy and the “Word Hoard”: “You might say that Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine, Nova Express, The Ticket That Exploded all derive from one store of material a good part of which was written between 1957 and 1959” (ROW, 243). You might say is an equivocation in itself, a telltale sign of what he should not have said, and Burroughs was saying it in order to defend his third edition of The Soft Machine against the hostile criticisms of Brion Gysin (to which we’ll return). Burroughs overstated the manuscript origins of the trilogy as a way to justify his new version to Gysin—“The assemblage of a book from this material is always hurried and arbitrary”—but he was also echoing the story of the book from the beginning, six years earlier.

“OUT OF A HAT”

By early December 1959, Burroughs had come up with a new title, “But Is All Back Seat Dreaming.” Initially used for one section sent to Big Table magazine, the title was soon applied to the book as a whole—which, he now told Ginsberg, he had “written most of,” “remaining only the task of correlating material” (ROW, 10). This was premature, and almost a year later he was again telling Ginsberg of his “next novel which is only a problem of putting it together,” even as he admitted it was an “inordinate amount of work” (59). In April 1960 Burroughs had moved from Paris to London and changed the title again, informing Gysin that he had “been writing a sequel to Naked Lunch to be called ‘Mr Bradly Mr Martin’” (25). In the first edition, “all back seat of dreaming” and “mr. bradly mr. martin” would be the titles of the final two sections. Meanwhile, Maurice Girodias began pressing him for a contract on the new book and in early August 1960 Burroughs quipped to Gysin, “Does he know what exactly he is trying to buy?” (42). It was a good question, bearing in mind the feedback Burroughs received on his work in progress later that month from Paul Carroll, who had published “Back Seat” in Big Table.

Speaking “frankly,” Carroll tried to balance faith in Burroughs with deep scepticism about this “new, difficult work” which had “moved so far from NAKED LUNCH.”8 Burroughs’ reply is instructive. On the one hand, he promised to send “something else as near as possible” along “straight narrative lines,” and on the other he tried to reassure Carroll that the new material would be “readily understandable” once he saw the larger structure of which it was a part.9 Only four months earlier, when returning the corrected proofs of “Back Seat,” Burroughs had shown he already recognized that his cut-up texts needed framing for the reader, sending Carroll a “note on the method used, to be printed with the material” (ROW, 22). In other words, so far as Burroughs was concerned, he was taking measures to ensure the readability of what, in January 1961, he at last named The Soft Machine.

The “note on method” that Burroughs had sent to accompany “Back Seat” in April 1960 was a short, early version of a much-circulated and often-quoted text, an expanded version of which appeared in The Third Mind: “The Cut-Up Method of Brion Gysin.” When it was first published under this title later that year in Sidewalk magazine, Burroughs described it as an “explanation” that was “inseparable” from the Soft Machine material published alongside it (entitled “Have You Seen Slotless City?”)10 The note began by tracing the method’s origins in avant-garde history: “Tzara at a Dada Meeting in the 1920s proposed to create a poem on the spot by pulling words out of a hat” (ROW, 22). Burroughs used the resonant final phrasing again when telling Paul Bowles in January 1961 of his “sequel to Naked Lunch entitled The Soft Machine. Cutting and permutating the book writes itself out of a hat” (65). By this time he had been working solidly for eighteen months and was still struggling to cut his manuscripts into shape—“I have so much material here it appalls me to see it” (57), he had despaired in late 1960—so his talk of pulling a book out of a hat was, like Tzara’s original act, a stunt rather than a description of creative process. It wasn’t only his enemies who would throw Burroughs’ words back at him (as hostile and uncomprehending reviewers did, deriding his work as a lazy gimmick): Kerouac dismissed cut-up methods as “an old Dada trick” and Gregory Corso, in a post-script to his own contribution in Minutes to Go, rejected cut-ups as, precisely, old hat: “Tzara did it all before.”11

Burroughs was guilty of promoting cut-ups too simplistically—the message of his early polemics was always: “Method is simple”—but this was precisely because of his evangelical zeal to promote them as widely as possible. It wasn’t a Dada prank, and while The Soft Machine shares more than a similar title with modernist experiments like Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, Stein didn’t believe her creative techniques were also revolutionary tools for her readers to use. In absolute contrast, Burroughs’ “note on method” ended by declaring: “The old word lines keep thee in old world slots. Cut the word lines.” Burroughs therefore tried to distinguish his new work from high modernists and the historical avant-garde both aesthetically—“important to avoid old surreal look,” he wrote to Paul Carroll in January 1961 regarding the use of typeface12—and, above all, politically. It was in this context that he coined the term “soft machine” in late summer 1960.

“THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE BATTLE

INSTRUCTIONS”

In his 1960 version of “The Cut-Up Method of Brion Gysin,” Burroughs played the role of guide to his own work by mapping it in four ways: one context was art-historical (referring again to “Tristan Tzara at a Surrealist Rally in the 1920s”), another was that of contemporary science (naming the mathematician John von Neumann, whose “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior introduced the cut up principle of random action into military and game strategy”), and a third was entirely open-ended (“Applications are literally unlimited”). The final context was a sharp negative: “The method was grounded on The Freudian Couch.” For Burroughs, opposition to cut-up methods was inseparable from their creative potential and subversive political importance, and identifying enemies was as necessary as trying to convince sceptics or recruit allies in what he saw as not a literary endeavour at all, but essentially a war. And when he picked up the Stanley knife from Gysin in October 1959, he stabbed it first into Sigmund Freud.

In part, the attack on Freud reflected Gysin’s own agenda, his dispute with what he referred to in Minutes to Go as “the Art Wing of the Freudian Conspiracy calling itself Surrealism,” and in part it was personal.13 Burroughs had had two decades’ experience of psychoanalysts, but when Gysin introduced him simultaneously to cut-ups and Scientology he immediately made a connection between them as mechanistic methods that promised fast and radical results, ways to cut himself out of the past and to cut the past out of him. The fingerprints of L. Ron Hubbard, pulp science fiction writer as well as cult prophet, are all over the Cut-Up project: from its manifesto Minutes to Go, where he is quoted and effectively named as a fifth collaborator, to the Nova conspiracy scenario and the therapeutic techniques using tape recorders advocated in the trilogy, although only odd references (e.g., “words engraved on my back tape”) appear in The Soft Machine.

As quickly as Burroughs decided that the cure was as simple as cutting up words on tape or on paper, he identified the plot against it. In writings from late 1959 onwards, he blasted psychoanalysis as “one of the vilest conspiracies of all time,” aimed at spreading mental illness, serving power elites, and actively blocking cut-up methods.14 In the screaming block capitals typical of 1960 typescripts, he declared that “THE PRACTITIONERS OF PSYCHOTHERAPY ARE SHAMELESS OR STUPID MACHINE SENT LIARS AND FRAUDS”: “BURN THEIR STUPID BOOKS. CUT HERR DOCTOR FRAUD INTO A MILLION PIECES. SEE IT FOR THE COMMUNIST SENT LIE IT IS […] THE SOFT MACHINE IS YOUR ILLNESS CUT THE MACHINE WORD LINES AND YOU WILL BE CURED.”15 The 1961 Soft Machine included one brief but telling reference to “fraud Freud and Einstein,” although this was dropped from later editions and little else would remain in his published work to indicate Burroughs’ deplorable subscription to the International Jewish-Communist conspiracy.16 Critics have preferred to turn a blind eye to it, but the anti-Semitism in his work at this time and an equally ugly misogyny were encouraged by Gysin, and represented the dark side of Burroughs’ self-declared megalomania, his missionary conviction of having discovered the secret weapon to combat a conspiracy of conspiracies. The Burroughs of unchecked paranoia was no “Friendly Prophet.”

It was in this context that Burroughs asked “WHO SERVES THE SOFT MACHINE?” and across dozens of texts identified a hydra-headed enemy comprising women (“FIRST THEY INVADED AND TOOK OVER WOMEN OF THE WORLD”), scientists (“PREACHING DEATH AND REALITY”), newspaper magnates (“MR LUCE BEAVERBROOK HEARST TIME SMASH YOUR MACHINE”), bankers and industrialists (“ROTHSCHILD ROCKEFELLER”), and computer technology (“THE HANDLING OF MILLIONS OF LIFE SCRIPTS IN SYMBOL FORM IS DONE NOW BY ELECTRIC COMPUTERS”). Burroughs’ megalomania placed him and the Cut-Up project center-stage in a global conspiracy, and in these texts he not only addressed his enemies directly but imagined the replies they would make to “WILLY THE RAT FROM MISSOURI” who had “CALLED THE LAW” on them.

As well as identifying language itself as the enemy—“THE SOFT MACHINE GOT IN BY THE WORD”—Burroughs specifically attacked the word and image media empire of Henry Luce. He addressed Luce and fantasized his reply (“STAND ASIDE BURROUGHS OF SPACE AND LISTEN TO THE LORD OF TIME”), while backdating the connection between Luce’s magazines and cut-up methods: “When Tzara first pulled words out of a hat the conspiracy of Life Time Fortune to monopolize Life Time and Fortune would have been smashed before it started.”17 The logic of conspiracy may seem simpleminded and run in reverse—a monopoly of news media developed because Freudians used Surrealism to stop the work of a Dadaist poet—but Burroughs was just taking the titles of Luce’s magazines at their word: they did indeed aim to copyright “Life” “Time” and “Fortune,” most literally in Luce’s championing of a permanent “American Century”—a world of American values that would run on American time, to the end of time. Fulfilling the thesis implied by chance in the very first cut-ups—when Gysin had accidentally chopped up Life magazine adverts with news items from the Herald Tribune—Burroughs’ trilogy evolved in direct opposition to Luce’s trilogy. What’s surprising is that, having identified Luce’s “Time Machine” with the “Soft Machine,” he made nothing of the connection in The Soft Machine itself, and instead made it central to Nova Express.

Beyond naming names and identifying monopolistic professions or institutions, Burroughs was attacking the false appearance of the world we think we know, and so ultimately he defined “THIS SOFT INSECT MACHINE AS THE IMMUTABLE REALITY OF THE UNIVERSE.” He tried out a variety of metaphors to clarify his concept: from “the soft machine is a virus parasite” to “PICTURE THE SOFT MACHINE AS A PUPPET MANIPULATOR,” and evoked it in terms of the archetypal American big con game (“THE BIG STORE. THE PROP BANKS”) as well as what he called a “new Mythology for the Space Age”: “THE SOFT MACHINE? AN OBSTACLE COURSE. BASIC TRAINING FOR SPACE.”18 Essential to the emerging science fiction scenario of his Nova Conspiracy was Burroughs’ conflation of his enemies into one all-embracing anti-human invader, against whom cut-up methods could be deployed by guerrilla forces of underground resistance. By early 1961 he had written the most explicit text he would publish on the subject, which appeared in the first issue of the New Orleans magazine The Outsider in fall 1961 as “Operation Soft Machine/Cut.” Laid out in newspaper-style columns—the precursor of many experiments in this format during the mid-1960s—the magazine version was never intended as part of The Soft Machine, but an earlier draft was.19 While the book is almost totally obscure about the big picture of the Nova Conspiracy and the meaning of Burroughs’ central term, the magazine text (included as an Appendix for this edition) is absolutely explicit: “The occupying power of this planet described as a soft MACHINE.”

Equally important, the magazine piece overlaps not just the book but also Burroughs’ two manifesto pamphlets, Minutes to Go and especially The Exterminator, suggesting the larger network of publications in multiple formats of which The Soft Machine published by Olympia Press was only one element. Indeed, two parts of the book appeared in 1960 and five more in 1961 in a variety of little magazines ranging geographically from the United States (Big Table in Chicago, Metronome in New York, The Outsider in New Orleans) to England (International Literary Annual), Scotland (Sidewalk), France (Two Cities) and Belgium (Nul). Altogether, 5,000 words of The Soft Machine appeared in print before the Olympia edition in June 1961, and another 5,000 during the six months after, adding up to almost a quarter of the text. Burroughs showed his commitment to book publication throughout the decade-long cut-up project—he would not have bothered to twice revise The Soft Machine otherwise—but from the start he also recognized the unique importance of little magazines and the underground press. Olympia was in many ways the ideal publisher for him—small, foreign-based, controversial, ambiguous in its mix of high literature and bad taste, from Lolita (1955) to There’s A Whip in My Valise (also published in 1961). Nevertheless, it made more sense to cite “Mao Tse Tung on Guerrilla war tactics” and to declare “THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE BATTLE INSTRUCTIONS,” in the crudely typed hand-printed pages of a counter-cultural magazine like The Outsider.

“THE WORD-STRIP”

The 1961 Soft Machine mixes elliptical episodes of science fiction fantasy with ethnographic travelogue, repetitious sex scenes, pulp genre parodies, and a variety of unclassifiable and uncompromising language experiments. The text is so relentlessly bizarre that it seems simultaneously impossible to read and yet—unlike the second and third editions, where the reader is left confused by non-narrative sections—not in the least frustrating. Instead of a narrative scenario, it is dominated by long image-lists (redolent of, and sometimes cutting up, the prose poems of Rimbaud and St.-John Perse) that depict toxic landscapes—swamps, jungles, canals, rotting cities of concrete pillars and bamboo bridges—and whirling machinery—penny arcades, Ferris wheels, pinball machines, cable cars, elevators. Ginsberg described it as “page after page of heroic sinister prose poetry.”20 Although the polluted wastelands clearly develop out of Naked Lunch, the dominance of South American locations and the recurrent use of Spanish signals Burroughs’ vision of a new global colonialism, the planet’s occupation by an alien empire: Trak Utilities—the dominant corporation in The Soft Machine, precursor of the Nova Mob in Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded—extends the imperial ambitions of sixteenth-century Conquistadors from the New World to the whole of reality. (“You can’t walk out on Trak,” Burroughs would clarify for the revised text; “There’s just no place to go.”)

It therefore comes as less of a surprise to discover that in spring 1961 Burroughs planned to incorporate into The Soft Machine another type of stylistically anomalous material; his 1953 epistolary report on Central and South America, “In Search of Yage.” According to Paul Bowles, it was only because “Girodias was hurrying him towards the end” that about thirty pages of this material did not go into the book.21 Burroughs made up for it by creating overlaps between his revised edition of The Soft Machine and “In Search of Yage,” building into The Yage Letters a cut-up text (“I Am Dying, Meester?”) much of which he incorporated into the new Soft Machine. The connection Burroughs made across books was as much formal as geographic or thematic, associating the hallucinogenic yagé vine with cut-up techniques as twin methods of sensual derangement, linguistic transcendence, and visionary transport to other worlds. Archival typescripts confirm the association: Burroughs made an extensive cut-up of his 1953 “Composite City” vision, whose yagé-inspired montage poetics anticipated The Soft Machine by pointing to the organic fertility of words in recombination.22 The environmentalist politics implied by Burroughs’ use of South American topographies therefore coincides with an intriguing textual ecology. Rather than being made to express meaning, phrases spontaneously replicate, duplicate, permutate, animate. Burroughs had long wanted to “create something that will have a life of its own”—an ambition he opposed to writing a “novel,” which is “something finished, that is, dead”—and in The Soft Machine his mechanical methods do create a strange, stuttering version of autonomous life.23 What is most inspiring about the 1961 edition is therefore not its intermittent flashes of open insurrection but its use of language. For political ferocity it has nothing on Nova Express, and it lacks the pragmatic polemics of The Ticket That Exploded, but where else can we encounter the imperative “Walk scorpion hair. Room violets,” or “shredded clouds impregnated with flesh fur of steel”?

In narrative terms, the 1961 text is virtually static, and at a sentence level it is paralyzed by the lack of active verbs. In other volumes of the Cut-Up Trilogy, Burroughs gave his fragmented writing forward momentum by using the em dash (—) and ellipsis ( . . .); here the dominant punctuation mark is the staccato period stop.24 Combined with The Constant Capitalization Of Words, the result is unreadable as a narrative. Instead, individual phrases possess an inspiring alien energy, the dynamic vitality of composites made from wildly incompatible terms: “Brass entrails from other twilights. Fur youths in glass hunger down the bones. Spit blood crystals of dawn. Masturbating broken mirror rocks.” It’s “unreadable” in the sense of being impossible to read without being forced to wonder what “reading” is at all. The effect is viscerally and philosophically bracing, for a while. The other volumes in the Cut-Up Trilogy also suffered a law of diminishing returns, but, unlike the first Soft Machine, they took advantage of their length to generate recurrent effects of déjà-vu, creating an uncanny dimension of disturbed memory missing from the 1961 text.

Comparing the first to later editions, what Burroughs left out of The Soft Machine seems logical: from a paragraph where almost every sentence begins “And” to an 84-word long sentence punctuated by just one comma, and from pages of phrase permutations and word fragments to sections like “the word-strip,” which begins: “I am that I am yo soy lo que soy je suis ce que je suis Ich bin das Ich bin ana eigo io ese quello io eseyo soy ca je suis soy am est eso ana ist that eso am es ich das ce que bin am that quello eigo soy eso am ist ese quiego sat that am ce que ist is es am cat dam anoy iegos oys soys boys tat ta hat tama taick sick joys ass quam loy st ickythyyoanncnesnsosnnntatatamattatmattamaick-sick soy cn es n sos nnn.”

The other key feature of the 1961 Soft Machine is its unique structural organisation into color Units (Red, Green, Blue, White), only traces of which would remain in later editions. The structure came from Rimbaud’s poem “Voyelles” (minus black), and also reflected Burroughs’ intense preoccupation with color stimulated by other sources, including the drugs yagé and apomorphine and the orgones of Wilhelm Reich (all associated with blue), and the work of the British neurophysiologist, W. Grey Walter.25 In spring 1961 Burroughs was taking mescaline and developing what he called “color line walks” around Tangier, both of which responded to Aldous Huxley’s mescaline-influenced lament that modernity had killed the magic of color (“We have seen too much pure, bright colour at Woolworth’s to find it intrinsically transporting”).26 Burroughs’ writing was just one in a range of experimental practices in different media that were visually-oriented, so it was logical that, after submitting his manuscript to Girodias in April 1961, he would go back to the beginnings of the book by turning to Brion Gysin for cover artwork.

Gysin was duly credited with the jacket design—impressive, if rather grey calligraphic forms, replaced by Burroughs’ colored ink drawing on the cover of the second edition—but his name is otherwise absent from The Soft Machine. This is in marked contrast to Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded where Gysin is referenced several times and credited in prefatory notes along with other collaborators. And yet the 1961 edition was, more than the later volumes in the trilogy, a collaborative production involving both Gysin and Allen Ginsberg (who wrote the unsigned jacket blurb). Not only did Gysin and Ginsberg correct the proofs for Burroughs that April—help he always sought, since he was a poor proofreader—they helped organize the final manuscript, working together in Paris while Burroughs was away in Tangier. Unlike Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded, which he wrote in sections or chapters, what Burroughs left behind for submission was a largely continuous text. The published book is subdivided into fifty short titled sections, whereas the typesetting manuscript had only nine—four of them handwritten in the margins by Burroughs in blue ink—plus a number of line-space breaks. As well as trying to give the reader some space to breathe by inserting the section breaks at more or less regular intervals, Gysin and Ginsberg also both wrote blurbs to help promote the book, as indeed did Gregory Corso.

Corso’s short piece suggests the extreme difficulty even those closest to Burroughs had in describing The Soft Machine (“a fine epitome of the cut-up” was the best he could manage), while Gysin’s two-page typescript focused on the book as “a journey into the unknown,” on Burroughs’ mythic persona (“Tall, thin, oyster-pale, a bit stooped and transparent”), and his expertise in plant hallucinogens (“poppy, hemp, coca, bannesteria caapi, sacred mushrooms”).27 Ginsberg’s handwritten draft is interesting for what was left out of the blurb used on the Olympia jacket, including claims that the cut-up method was “applicable” to both psychoanalysis and politics, and a striking final quotation which advocated Burroughs’ method as hope for colonized peoples: “Sola esperanza del Mundo—Take it to Cut City.” However, despite his enthusiastic gratitude for the blurbs, disagreements began even before the book was published: “I cannot agree with Allen about the ending,” he wrote Gysin, admitting that “the book is experimental and difficult” but insisting, “I can’t do it over” (ROW, 75)—and yet that’s exactly what Burroughs decided to do.

“YOU HAVE TO WRITE FINIS”

The publishing history of The Soft Machine makes it entirely obvious that the book changed from the first edition published by Olympia in June 1961 to the second edition published by Grove in March 1966, because for five years everyone told Burroughs the same thing—that it was too difficult to read—and so he made it less cut-up and more readable when he moved publishers. It is equally obvious that the same logic also applied for the third edition published by John Calder in July 1968. And yet what’s obvious turns out to be wrong.

To begin with, Burroughs didn’t need to wait five years to recognize that The Soft Machine was almost unreadable. When Timothy Leary visited Tangier to take hallucinogens with him at the end of July 1961, he reported Burroughs’ reflections on the book published just a month earlier and his determination to write a different one next time: “The soft machine is too difficult. I am now writing a science-fiction book that a twelve-year old can understand.”28 The new book was Nova Express, and while Burroughs’ idea of what pre-teens could read is a stretch or a joke at his own expense, the point remains that the second volume of his Cut-Up Trilogy was defined against his first.29 What led Burroughs to revise The Soft Machine, however, was not general regret or negative feedback from friends, but the publishing contract for a specific book. In August 1962 he starred at the Edinburgh International Writers’ Conference, coordinated by the Scottish publisher John Calder who commissioned Burroughs to make a book of selections from his Olympia Press titles (Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine, and The Ticket That Exploded) in order to pave the way for Calder to publish Naked Lunch in the UK.30 As he began compiling Dead Fingers Talk that September, Burroughs told Paul Bowles: “I am very much dissatisfied with The Soft Machine and had to rewrite most of the material included in the book of selections” (ROW, 114). One opportunity to rewrite the book led directly to another.

The months following his success at the Edinburgh Conference were a crucial time for Burroughs’ Cut-Up Trilogy. Assembling Dead Fingers Talk coincided with revising The Soft Machine, completing The Ticket That Exploded and submitting a new draft of Nova Express. In November 1962, Burroughs updated Bowles to say that he had now finished rewriting The Soft Machine, adding the expected verdict “and it seems a lot easier to read.”31 The manuscript he completed in late November 1962 is almost certainly the 129-page typescript archived at Columbia University, identified by Burroughs as “the original manuscript of the rewritten and revised version of The Soft Machine.”32 It is very similar to the book published by Grove in 1966, which means that, far from being separated by five years, the first and second editions were effectively only eighteen months apart.

Just as significantly, while Burroughs invited interest from Grove Press—sounding out Barney Rosset that October—he didn’t rewrite The Soft Machine for a new publisher but once again for Olympia. The clearest evidence for that is the otherwise confusing note printed in The Ticket That Exploded published by Olympia in December 1962, which advertised a “New revised and augmented edition” of The Soft Machine scheduled for February 1963. The month the book was meant to appear, Girodias apologised for his failure to publish it (“The money situation is bad . . . very bad”), testing Burroughs’ loyalty to the man who had published Naked Lunch but who never cut a straight deal.33 For the next eighteen months Burroughs repeatedly asked Girodias whether he was arranging a contract with Barney Rosset or John Calder for the revised Soft Machine, and was discouraged to find himself caught in “a bitter feud” between the American and British publishers that was still ongoing in spring 1965 (ROW, 189). The final stages of the book’s publication were complicated enough without a backstory in which publishers who fought the law to publish Burroughs ended up in legal fights with each other.

Indeed, Richard Seaver at Grove Press had a problem with Burroughs’ continued revisions, which didn’t end at the galley stage in October 1965;34 when Burroughs requested still more changes in December, at the risk of sounding “like an old St. Louis preacher” Seaver insisted “there comes a point at which you have to write finis to the writing of a book.”35 Burroughs persisted, however, in early January 1966 sending even more new material; but it was now too late for further changes, and all Seaver could do was respect Burroughs’ reluctance “to let the book go until you’re fully satisfied with it.” The idea of Burroughs being fully satisfied with any of his cut-up books was a kind of philosophical category error, because his methods did not lend themselves to “finish” in any meaning of the term. When he said of Nova Express that it was not “in any sense a wholly successful book,” or of The Ticket That Exploded, “It’s not a book I’m satisfied with,” it was the book as a form that really dissatisfied him.36 Nevertheless, he tried to succeed with Calder where he had failed with Grove, and at the end of January Burroughs submitted to him the revised manuscript with all the new material that Seaver could not accept. In fact, in summer 1966 Burroughs sent Seaver the manuscript and then in October the galleys for the Calder edition, seemingly in hope Grove would release it too, but without success. In a final twist of misleading appearances, the book Calder published in Britain in July 1968—more than two years after the Grove Press edition—was simply what Burroughs had submitted in January 1966, two months before the Grove edition came out.

Which leaves us with two questions: how exactly did Burroughs’ revisions change The Soft Machine from edition to edition? And how does this new edition aim to advance such a perplexing history?

“WHAT THE BOOK IS ABOUT”

“I have completely rewritten it,” Burroughs told Alan Ansen in January 1963, “taking out most of the cut ups and substituting sixty-five pages of new material in a straight narrative line.”37 Needless to say, it was not as straightforward as that.

In raw statistical terms, to make the second edition Burroughs retained just under half of the first edition and, since the two books are very similar in length (38,000 words), the result was that half of the second edition was old writing, half new. Comparing the first three chapters of the 1966 edition to the 1961 text, at first sight Burroughs’ revisions seem simple enough: the first and third chapters reuse continuous material from the earlier book, while the second chapter is all new and uses no first edition material at all. However, after this point the majority of chapters consist of highly complex combinations of new and old. Burroughs changed and radically re-sequenced most of the 1961 material, which was also very unequally distributed across the book as a whole: the first half of the 1966 text (up to and including the long, newly written narrative “Mayan Caper” chapter) is only one-third based on material from the 1961 edition; in contrast, the second half of the 1966 text, starting from the “I Sekuin” cut-up chapter, is nearly three-quarters based on the 1961 edition.

There was a broad logic to the kind of material Burroughs did and did not retain from the 1961 text for the 1966 edition, but some of his choices are unexpected. For example, he didn’t use one of the first edition’s longest narrative sections, entitled “lee took the bus”—only to change his mind and include it for the third edition. And on the other side, while he compromised it by changing every word from upper to lower case, he did include the opening of “I Sekuin,” a stunning but very challenging cut-up section. Above all, it is not the case that Burroughs simply took out cut-up material and substituted straight narrative. The general direction of revision may have been toward greater readability, but far less emphatically than he implied. Roughly speaking, the first edition is 55% cut-up and 45% narrative, the second edition 30% cut-up, 70% narrative. However, if the majority of new material was narrative, some 6,500 words of it—over one third—was cut-up. Some of this new cut-up material, such as in the “Early Answer” chapter, is among the most dense and difficult in the whole book. The impact of the new narrative is also highly focused, since most of it appears in only two, all-new chapters, “The Mayan Caper” and “Who Am I To Be Critical?” Those two chapters are fast-paced, thematically clear and very funny (the humor of the 1961 text is easy to miss), but they don’t represent the book as a whole. In fact, the biggest surprise is to realize that the majority of narrative in the second edition actually came from the first edition and the majority of cut-up material was new. Indeed, of the roughly 10,000 words of cut-up material in the 1966 edition, only about a third came from the 1961 text. To say “roughly” is a necessary caveat, since once you start counting, the initially clear distinction between “straight” and “cut-up” becomes meaningless, which is one of The Soft Machine’s strangest and most fascinating effects.

As for the changes Burroughs made on the galleys in October 1965, they caused Grove Press difficulties because there were so many of them: the margins of almost every sheet are crowded with the repeated instruction in his distinctive hand: “No Caps.” “COST OF CHANGING UPPER CASE TO LOWER THROUGHOUT SOFT MACHINE, SEVERAL HUNDRED DOLLARS STOP,” Seaver cabled him in early October; “IS IT ABSOLUTELY ESSENTIAL CABLE REPLY.”38 Burroughs must have replied in the affirmative, but at that stage made relatively few actual cuts or insertions. He added the 1,000-word narrative about Salt Chunk Mary and another 500 words in half-a-dozen short inserts scotch-taped onto the galley sheets. He also made some two-dozen short cuts adding up to about 500 words and, in his major late decision, retained just one paragraph from a cancelled chapter of almost 1,000 words. What this means in terms of content is that 95% of the book published in March 1966 was present in the “1962 MS” (i.e., the 129-page typescript probably submitted to Olympia Press in late November 1962). There were differences in presentation and structure, however—and they are highly significant for this new, fourth edition of The Soft Machine which has gone back to the 1962 MS as the basis to revise the text.

The manuscript Burroughs completed in November 1962, which was scheduled to be published by Olympia in 1963, differs from the second edition in three main ways: it lacked the 1,500 words added to the galleys in 1965 and included the chapter of 1,000 words cancelled at the same stage; its chapters begin and end more often in keeping with the third than the second edition; and it made far fewer changes to the appearance of the material taken from the 1961 text. This fourth edition includes everything published in the second edition, while respecting the 1962 MS’s chapter divisions and restoring the cancelled chapter, entitled “Male Image Back In.” Burroughs had also cut a chapter at the final galley stage for Nova Express, but that was long and highly repetitious, whereas this short chapter works well in The Soft Machine, and he retained a little more of it in the third edition.

In the most visible change, this new edition also restores how material from the first edition appeared by putting back a thousand capital letters removed on the galleys in 1965. Changes to capitalization are a major feature of Burroughs’ revisions to the Cut-Up Trilogy, and he revised on a massive scale in both directions: on the galleys of Nova Express in 1964 he changed from lower to upper case; and for the second edition of The Ticket That Exploded in 1967, he changed from upper to lower. Burroughs’ own apparent inconsistency doesn’t lend itself to consistent editing across the trilogy. However, restoring capitals for The Soft Machine makes sense since the second edition was the odd one out: following the 1962 MS means respecting the appearance of both the first and the third edition, which largely retained capitals. It also brings The Soft Machine visibly closer to how Burroughs reconceived it in late 1962—the period when he was working simultaneously and most intensely on all three volumes of his trilogy.

The main reasons for turning to this 1962 manuscript in the first place are pragmatic: while there is something suitably Burroughsian about the status quo, with two quite different versions of The Soft Machine remaining in print, the great majority of readers have had to accept the edition that failed to grant Burroughs his “final intentions,” as textual editors used to say. However, the obvious alternative—to let the third edition replace the second—is even more unsatisfactory. Although Burroughs actually preserved more of the 1961 text in the British edition of 1968, through what he added much more was lost. This is the paradoxical value of his 1962 MS; in content it is close to the second edition, while in the appearance of its material it is close to both the first edition—his original—and the third edition—his last word on the book.

When Burroughs mailed his manuscript to John Calder in late January 1966 he observed that he had “added approximately 45 pages of single space material” together with “an article on the apomorphine treatment as an appendix.”39 In statistical terms, for the third edition Burroughs cut 1,500 words from the second edition and added about 19,000 more, almost 6,000 in the Appendix. Of the 13,000 words added to the main text, some 3,000 were previously unused material from the 1961 edition and the rest were new. The new material reflected Burroughs’ writing in late 1965, especially a distinctive narrative style of great economy, evocative power, and simple, minimally punctuated prose. The end result was not just that the book became virtually 50% longer; it was quite simply a very different book—which was the basis to Brion Gysin’s objections.

In October 1966 Burroughs had invited Gysin to design a jacket for the Calder edition and although he could “not think how to do a new cover,” Gysin was anxious to see “the final revision” of a book of which he had “always been very fond.”40 When Gysin saw the page proofs in November he bluntly stated that the result of Burroughs’ revisions was “of course, no longer SOFT MACHINE.”41 Speaking of the long appendix article that lambasted U.S. drug policy, Gysin protested: “The apomorphine material—if you will excuse me and I presume you won’t—absolutely does not belong in the same book with the rest.” He was surely right: the article made an odd ending to The Soft Machine, where the drug is mentioned only once.42 Gysin thought Burroughs had lost his way, not just at the end but from the start of the revised edition: “Please, if you can, switch back to the original opening. That’s what the book is about, isn’t it?”

Gysin’s suggestions to restructure The Soft Machine were impractical then and would be misguided now. The evolutionary logic of the book can’t be put into reverse, any more than it can remain frozen in time or turned toward perfection. But his objections are revealing for the response Burroughs made to them. Instead of arguing over what his book was “about,” he spoke at length of the trilogy’s complex manuscript history and of having been right to choose “straight narrative” for the beginning because of what others found more “readable” (ROW, 243). At the time of revising The Soft Machine in September 1962, Burroughs defined “straight narrative” in terms of Naked Lunch (114)—not a definition anybody else would use—and in that context it made sense to begin the book with “Dead On Arrival,” a chapter originating in early Naked Lunch manuscripts. What’s strange is Burroughs’ persistence in using the term straight and his application of it to “Dead On Arrival,” since the text is an object lesson in the queering of narrative, which makes it an ideal start to The Soft Machine, a sort of guidebook to what follows.

The first line of “Dead On Arrival” (“I was working The Hole with The Sailor”) returned The Soft Machine to the realist, autobiographical world of Burroughs’ first novel, Junky, and echoes the moment in it when William Lee begins to support his heroin habit by rolling drunks on the subway: “The H caps cost three dollars each and you need at least three per day to get by. I was short, so I began ‘working the hole’ with Roy.”43 The hole is an underground term for the underground itself, and the joke in Junky is that Lee and Roy (the Sailor) work there to support their habits, in a parody of the straight, above-ground working world. The narration is realistic and trustworthy, even though its values are subversive. For Naked Lunch, Burroughs had also taken an innocent-looking paragraph from Junky set on the subway, and twisted it to create the opening passage where Lee vaults a turnstile and catches an uptown A train to escape the law. In Naked Lunch, instead of narrating in a straight deadpan, however, Lee puts on the voice of a brazen hustler, a con man literally taking the reader for a ride and implying that’s all anybody ever does. It’s an invitation to suspect our own motives as much as his: he’s on the hustle, but what are we looking for?

Just as the beginning of Naked Lunch went back to rewrite Junky, so too The Soft Machine went back to rewrite Naked Lunch. “Dead On Arrival” takes the process of rewriting a step further by visibly re-writing itself, cutting up its own words in a beautifully judged poetic structure that queers not just the straight world but straight reality. “Dead On Arrival” is not more readable as narrative than the book’s original beginning (“The War Between the Sexes split the planet into armed camps”); it is about readability itself, about exposing our reading habits and the fixed narratives by which we live. Tracing a tragic orbit around the narrator, the chapter’s melancholic roll-call of the dead—deaths by overdose, drowning, hanging, stabbing—all come from Burroughs’ biography and point to our common narrative towards death. The premise of The Soft Machine is that, individually and as a species, we’ve been conned into embracing as natural a fatal realism. Although the scenario is elliptical and the tone elegiac, the message of “Dead On Arrival” is defiant: “No good. No Bueno.” The example of the text implies that cut-up methods look to chance as the only way out, a last desperate chance, sola esperanza del mundo.

The Soft Machine was always difficult, and Burroughs’ decade-long efforts to straighten it out and make himself clear were perhaps doomed to radiant failure. In the end, he too was an inefficient guide: “I make no claims to speak from a state of enlightenment,” he once wrote Jack Kerouac, “but merely to have attempted the journey, as always with inadequate equipment and knowledge (like one of my South American expeditions), falling into every possible accident and error, losing my gear and my way . . .” (Letters, 226). Burroughs’ messianic side is always redeemed by his humour, which is also an act of defiance, a refusal to be just another soft machine: You win something like jelly fish, Meester?

Oliver Harris

September 16, 2013

1. Joan Didion, “Wired for Shock Treatments,” Bookweek (March 27, 1966); 2.

2. Burroughs, The Yage Letters Redux (San Francisco: City Lights, 2006), 21.

3. References are to David Porush, The Soft Machine: Cybernetic Fiction (New York: Methuen, 1985) and Richard A.L. Jones, Soft Machines: Nanotechnology and Life (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004).

4. Undated typescript, The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library; 43.27. After, abbreviated to Berg.

5. The Letters of William S. Burroughs, 1945–1959 (New York: Viking, 1993). After, abbreviated to Letters.

6. Rub Out the Words: The Letters of William S. Burroughs, 1959–1974, edited by Bill Morgan (New York: Ecco, 2012). After, abbreviated to ROW.

7. Burroughs, Naked Lunch: the Restored Text (New York: Grove, 2003), edited by James Grauerholz and Barry Miles, 249.

8. Carroll to Burroughs, August 17, 1960 (The Paul D. Carroll Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library; 1.18). After, abbreviated to Chicago.

9. Burroughs to Carroll, August 23, 1960 (Chicago, 1.18).

10. Burroughs to Bowles, October 8, 1960 (Paul Bowles Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin; 8.10). After, abbreviated to HRC.

11. Kerouac, in Beat Writers at Work, edited by George Plimpton (New York: The Modern Library, 1999), 132; Corso, in Minutes to Go by Burroughs, Sinclair Beiles, Gregory Corso and Brion Gysin, (Paris: Two Cities Editions, 1960), 63.

12. Burroughs to Carroll, January 20, 1961 (Chicago, 1.18).

13. Minutes to Go, 43.

14. Nine-page typescript, ca. late 1959 (Berg 7.44).

15. All citations in block capitals in this and the next paragraphs are from un-sequenced typescripts, circa 1960 (Berg 48.22).

16. That this phrasing originates in openly anti-Semitic material is clear from several 1960 texts, including: “I RUB OUT THE WORDS OF MARX LENIN EINSTEIN FREUD FRAUD FOREVER. I RUB OUT THE WORD JEW FOREVER” (Berg, 48.22).

17. Nine-page typescript (Berg 7.44). See notes on the “Where You Belong” chapter for Luce’s presence in the “1962 MS” of The Soft Machine.

18. Undated typescripts (Berg 3.52; 49.14; 49.32; 9.24).

19. Parts had appeared in “Brief History of the Occupation,” which Burroughs started to write in October 1960 and which he described as “FROM WORK IN PROGRESS: ‘MR BRADLY MR MARTIN’”—his earlier title for The Soft Machine (Berg 10.47).

20. Ginsberg to Kerouac, September 9, 1962, in The Letters of Allen Ginsberg, edited by Bill Morgan (Cambridge: Da Capo, 2008) 270.

21. Bowles to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, July 24, 1962 (City Lights Books Records, Box 1, University of California, Berkeley).

22. A six-page typescript sequence, which includes elements of Soft Machine material such as Soul Crackers, features cut-up permutations of the “Composite City,” from “Expeditions leave for unknown boys” to “Yage is space games with motion” (William S. Burroughs Papers, Ohio State University, Columbus SPEC.CMS.87, 17.130A).

23. Burroughs, Interzone, edited by James Grauerholz (New York: Viking, 1989), 128.

24. The 1966 text has ten times the number of em dashes, almost 2,000; still far fewer than Nova Express or The Ticket That Exploded. The result is ironic, since the dash appears to be a visible sign of the cut, and the 1961 Soft Machine, the text with by far the fewest dashes, was the only true “cut-up” text in the trilogy, since Burroughs didn’t use “fold-in” methods for it, as he did for all other volumes.

25. The importance of Rimbaud from the start of the cut-up project is evident from references in Minutes to Go and The Exterminator. However, Burroughs’ use of “Voyelles” was more specifically associated with synaesthesia, hallucination, and the physiological effects of flicker, inspired by his reading of Walter’s The Living Brain, as a 1960 typescript makes clear: “WHEN I READ THIS PASSAGE I IMMEDIATELY THOUGHT OF RIMBAUD AND HIS IMAGES THAT SEEM TO BREAK DOWN BARRIERS. HIS COLOR VOWELS” (Berg 48.22). This was an artistic-scientific area emphasized by Ginsberg in his 1961 jacket blurb: “Stroboscopic flicker-lights playing on the Soft Machine of the eye create hallucinations.”

26. Aldous Huxley, “Heaven and Hell” (1956), in The Doors of Perception (London: Vintage, 1994), 76.

27. Gysin, “On The Soft Machine,” two-page typescript (Berg 5.37). Corso, untitled one-page typescript (Berg 5.39). Ginsberg, untitled two-page autograph manuscript (Berg 5.38).

28. Timothy Leary, High Priest (New York: Ronin, 1995), 225.

29. In another case of the trilogy’s misleading publishing history, Nova Express appeared two years after The Ticket That Exploded but was mainly written a year before, straight after The Soft Machine.

30. Of the thirty sections in Dead Fingers Talk, half feature material from The Soft Machine, although in all but three sections it is combined with material from one or both the other texts. In contrast, twice as many sections feature only material from Naked Lunch or The Ticket That Exploded. Burroughs also used more from those books than from The Soft Machine—another sign of his relative dissatisfaction with it.

31. Burroughs to Bowles, November 21, 1962 (HRC).

32. The manuscript is signed “Paris, June 1963”—a date probably added when Burroughs sold it.

33. Girodias to Burroughs, February 8, 1963 (Berg 75.8).

34. It’s likely that in early 1965 Burroughs submitted a manuscript of The Soft Machine to both Seaver and Calder—copies of a 162-page typescript, probably made in late 1962 or early 1963 for Olympia Press, cleanly retyped from the November 1962 MS.

35. Seaver to Burroughs, December 20, 1965 (Grove Press Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries). After, abbreviated to Syracuse; Seaver to Burroughs, January 14, 1966 (Syracuse).

36. Burroughs, The Job (New York: Penguin, 1989), 27; Burroughs Live: The Collected Interviews of William S. Burroughs, 1960–1996, edited by Sylvère Lotringer (New York: Semiotext(e): 2000), 77.

37. Burroughs to Ansen, January 23, 1962 (Ted Morgan Papers, Arizona State University; Box 1).

38. Seaver to Burroughs, October 6, 1965 (Syracuse).

39. Burroughs to Calder, January 26, 1966 (Calder & Boyars mss 1939–1980, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Box 66).

40. Gysin to Burroughs, November 21, 1966 (Berg 85.12).

41. Gysin to Burroughs, December 14, 1966 (Berg 85.12).

42. If the article belonged anywhere it was with Nova Express, where apomorphine is referred to three-dozen times, and Burroughs had indeed twice tried to interest Grove in adding an earlier version of the article to that text when submitting his first and revised manuscripts in spring and fall 1962.

43. Burroughs, Junky: the definitive text of “Junk” (New York: Grove, 2012), 36.