Читать книгу The Ticket That Exploded - William S. Burroughs - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“A SERIES OF OBLIQUE REFERENCES”

“OF COURSE, I’VE HAD IT IN THE EAR BEFORE”

A million people who’ve never heard of William Burroughs, let alone made it as far as the “operation rewrite” section of The Ticket That Exploded, can sing lines from the book. That’s because Burroughs’ book is where Iggy Pop found the raw materials of “Lust for Life”—it’s where Johnny Yen comes from along with those hypnotizing chickens and the flesh gimmick, the striptease and the torture film. The name is a typically Burroughsian composite, idiomatically mixing sex and drugs—a “Johnny” being both a condom and what goes inside; “to yen” meaning to yearn for it—which is why Johnny Yen comes again and is gonna do another striptease, and another. The repetitious lyrics recycle The Ticket to make Johnny a singing telegram for the endless bad kicks and insatiable lusts of consumer capitalism. Since Burroughs’ words have an indelible originality it’s no coincidence they’ve inspired an A to Z of musicians, writers and artists from Kathy Acker to Frank Zappa, but the art of recycling words was also the method of “operation rewrite,” Burroughs’ mission to kick the habit of language itself by cutting it up.

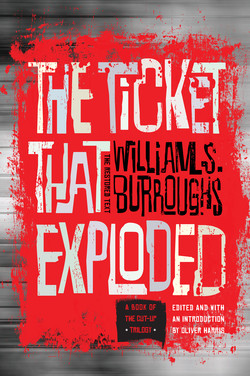

An outrageous hybrid of pulp science fiction, obscene experimental poetry and manifesto for revolution, The Ticket was part of Burroughs’ 1960s Cut-Up Trilogy, along with The Soft Machine and Nova Express. A lazy mythology has either damned or praised the books as crazy word collages thrown together at random, with the result that little is known about them—from the meaning of their titles to how they were written or how they’re supposed to be read—and their novelty remains simply shocking. The difficulty is that the urgency of Burroughs’ message goes together with the radicalism of his method, and The Ticket calls itself “a novel presented in a series of oblique references” because that’s the only way to get it: obliquely. In which case, before giving the backstory to its creation and clarifying how this new edition revises the text and its position in the trilogy, it makes sense to start with the musical history of a minor character—or in Burroughs’ own words, “with one average, stupid, representative case: Johnny Yen.”

Traces of The Ticket return in the lyrics of “Lust for Life” not just because Burroughs’ cultural influence has reached far and wide but more precisely because the book has produced a reception made in its own image. The Ticket is by far the most musically-minded of all Burroughs’ books, referencing the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and mixing fantasies of drum-playing Sex Musicians with a World Music sound-track that ranges from Moroccan flutes to the call of Irish bagpipes. Whole pages consist of nothing but song titles and sampled lyrics, collages of nursery rhymes and jazz standards, torch songs and blues ballads, cowboy tunes, Negro spirituals and Tin Pan Alley sentimental melodies. Iggy Pop knew this when he and David Bowie worked together on “Lust for Life” in West Berlin in 1977, so there’s nothing coincidental about Burroughs’ most musical cut-up book itself being cut up for the lyrics of a song: this was a case of “operation rewrite” in action.

Pop and Bowie probably knew the heavily revised 1967 edition of The Ticket, but had they seen the 1962 original they would have read the jacket blurb describing it as “an incantation sung by a crazy muezzin,” which turned book into song and writer into singer. In any case, they couldn’t have known that Burroughs actually planned to name his book either after a song—one with a Johnny in the title: “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair”—or after the act of singing itself—“If You Can’t Say It Sing It.” Far from being a sweet song of innocence, the title “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” symbolized Burroughs’ acute distrust of “the gimmick” referred to in Iggy Pop’s lyrics as “something called love.” The Ticket not only proposes that love lyrics communicate love sickness but that the essential human activities of communication and love are both a sickness. The other title, “If You Can’t Say It Sing It,” also spelled out the extremism of Burroughs’ book, privileging singing over speaking to point beyond verbal expression and exchange altogether. As the text bluntly says: “There are no good relationships—There are no good words—I wrote silences.” The “ticket” in the title he finally chose is an image of hidden determinism that invokes the insides of music machines, like the punch cards in an old fairground organ or the perforated rolls of a player piano. The Ticket That Exploded also sums up the other titles in Burroughs’ trilogy, The Soft Machine and Nova Express: as a figure for cultural and genetic programming, the “ticket” is written into us on the “soft typewriter” of the body, and it is “exploded” after a countdown to nova that is for Burroughs our only hope of rewriting the scripts that dictate our lives.

Burroughs is relentless to the point of tedium, but eventually we get the point: words don’t just describe something, through repetition they make it happen, so that the future is in effect prerecorded by the past. The “do you love me?” section which precedes “operation rewrite” accordingly slices and dices romantic songs to diagnose desire as an infectious disease, a communicable fever kept going by the repetitious lyrics of mass culture like a fairground ride going round and around, drumming and humming away in our heads. Cutting up old song lyrics, Burroughs sadistically mocks the sentimental longings they evoke and the result is a paradoxical composite typical of The Ticket and one reason this was the book that hooked me as a reader of Burroughs: the viciousness in its treatment of words somehow produces moments of a yet more haunting lyricism. It’s “the old junk gimmick” that identifies Burroughs’ text as both research into and a performance of the self-replicating virus of cultural communication that the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins called a “meme.” From memorable tunes to seductive ideas, memes spread themselves about, influencing and infecting, copying and mutating, and exhibiting their own autonomous and insatiable lust for life. As Burroughs reminded his cut-up collaborator Brion Gysin in loud block capitals in summer 1960, two years before starting his book, “YOU KNOW HOW CATCHING TUNES ARE.”1

Burroughs certainly had an ear for what was catching, and despite its often disorientating difficulty, his work is seductively quotable. This quality went together with a politically sharp sense of his own inescapable complicity in what he opposed: cut-up methods were a way to bring the verbal virus out into the open and to fight fire with fire. Burroughs noted that he and the poet John Giorno once “considered forming a pop group called ‘The Mind Parasites,’” on the basis that “all poets worthy of the name are mind parasites, and their words ought to get into your head and live there, repeating and repeating and repeating.”2 While he probably took the band’s name from the title of Colin Wilson’s novel, there’s also an echo in it of what Burroughs had found back in October 1959, when he first began to work with cut-up methods at the Beat Hotel in Paris. In a typescript explaining how “WORD LINES” dictate our “LIFE SLOTS,” he described how cutting up audiotape revealed noise in the cybernetic system that had a life of its own: “LIKE INTERFERENCE ON THE RADIO. ‘PARASITES’ THE FRENCH CALL THAT SOUND. GOT IT? IT GETS YOU.”3 It is in this sense, of the word as an alien organism, that The Ticket cuts words up and splices them back in together, treating text like audiotape in order to hear how the language virus works at the molecular level: “biologists talk about creating life in a test tube . . all they need is a few tape recorders.”

The Ticket also explores how the meme migrates from one medium to another, modeling the kind of media-crossing, collage-based cultural practices that Iggy Pop and David Bowie experimented with in the late 1970s and that in the digital age we take for granted. Framing The Ticket in terms of not one medium but four, Burroughs starts with an Acknowledgment that credits four collaborators, thanking Michael Portman, Ian Sommerville, Antony Balch, and Brion Gysin respectively for contributions in writing, audiotape, film, and artwork. It’s an astonishing opening note for what looks like a novel. But since The Ticket abjures the development of plot, character, or the texture of daily human life, it is no more a “novel” in any conventional sense than Burroughs is a “writer.” We have to bear in mind that it was part of not only a Cut-Up Trilogy but of a much larger, decade-long experiment—the Cut-Up Project—that crossed media and treated the book as one technology among others. The Ticket was both prescient and productive, inviting the cut-up lyrics of “Lust for Life” and mapping out the multi-media career trajectory of the Pop-Bowie collaboration from the moment the two musicians found inspiration watching TV one day. What prompted them was the U.S. Armed Forces station ID, whose signal ironically echoed the refrain of guerrilla resistance that runs throughout Burroughs’ book (“From the radio poured a metallic staccato voice […] ‘Towers, open fire’”): “At four o’clock in the afternoon,” Pop recalled, “the channel came on with this black-and-white image of a radio tower, going beep-beep-beep beep-beep-ba-beep,” and Bowie reportedly turned to him and said, “Get your tape recorder.”4

Just as television, radio, and audiotape segued naturally into one another in the process of musical composition, so too the song’s success mirrors back the collage aesthetics and cultural appropriations of Burroughs’ Ticket. It’s only natural that “Lust for Life” didn’t become a major hit simply because of its stomping drum reverb and ferociously sung yet witty lyrics but because it was borrowed for the film adaptation of the novel Trainspotting, whose subject matter (heroin addiction) owed a debt to Burroughs that went without saying. What does need to be said is that the success of the song via the film of the novel acts out the viral logic that is the subject of the book by Burroughs that inspired the song in the first place. And if it was inevitable that Pop would quickly cash in and franchise “Lust for Life” for crass commercial use, Burroughs could see that one coming too. In The Ticket he shows his scorn for how lustfully capitalism sucks the life out of everything and everyone by proposing what he calls “creative advertising,” so that his book’s revolutionary hero can sell out to the Nova Mob, the 1% who are screwing our planet, by promoting the deadly top brand of commodity addiction in “advertisements that tell a story and create characters Inspector J. Lee of the Nova Police smokes Players.”

In the context of this Madison Avenue parody, it may seem like a joke about product placement that at this point in The Ticket Burroughs makes numerous references to “the Philips Carry Corder.” In fact, the references establish a point of intersection between his book, 1960s music and the counterculture more broadly—a nexus that in turn predicts possibilities fulfilled by the digital environment of the twenty-first century. Tape recorders played a part in Nova Express through “The Subliminal Kid,” and in the original 1962 edition of The Ticket, but for the 1967 book Burroughs expanded their role through new narrative episodes and, most importantly, in sections advocating their practical use. Burroughs’ invitation to readers to follow his example by conducting experiments in cutting and mixing tape on their own equipment (“Go out and buy three fine machines”) went back to the launching manual of cut-up methods, Minutes to Go (1960), and technically updated it. Giving away a tool for active individual production rather than advertising a product for passive mass consumption, the manifesto had opened with Gysin’s announcement that “the writing machine is for everybody do it yourself.”5 Introduced in Europe in 1963, the compact audio cassette was a major breakthrough in portable technology at affordable prices, and in fall 1965 Burroughs bought a Carry-Corder 150, the model used by Ian Sommerville, his close friend and a technical adviser who Burroughs shared at this time with Paul McCartney. “Guess you’ve all seen the Philips Carry Corder,” he comments, directly addressing a youth audience defined by their interest in both the latest technology and popular music: “suppose you are a singer. Well splice your singing in with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Animals.” This was, Burroughs optimistically hoped, a potentially new revolutionary class that could be mobilized to take over the means of reality-production, as indicated in his play on Marx’s rallying cry: “Carry Corders of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your prerecordings.”

Immediately after completing his revised manuscript of The Ticket in October 1966, Burroughs told Gysin that his aim was “to get the children exchanging tapes.”6 That was also why he wrote a further expansion of this material as “the invisible generation,” an essay appended to The Ticket that was first published in The International Times, the major British underground newspaper. Confirming the media-crossing circularity of influence, IT was launched that same October with a gig in London featuring Pink Floyd and a recently formed band named after another book in the Cut-Up Trilogy, Soft Machine. Although now in his early fifties, Burroughs was being ironic in stressing the generation gap, aware as he was of his rising cult status in the 1960s youth counterculture. The revised edition of The Ticket was published in June 1967, the same month the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—with Burroughs’ now iconic face on Peter Blake’s Pop Art album cover.

“AT THE FAIR”

The Ticket That Exploded is a pastiche and bricolage of materials including fragments from “the Shakespeare squadron,” especially Joyce and Eliot, whose own major works were pastiches and bricolages of materials. But since The Ticket was part of a larger experimental project whose means were multi-medial and whose research goals were as scientific or political as they were artistic, the literary frame of reference is in some ways misleading. This is one of the genuine peculiarities of a Burroughs book; that it can seem both literary and viciously anti-literary at the same time, and the same goes for his cut-up methods. On the one hand, they were scandalous chance operations that seemed to reduce artistic creativity to the “writing machine” described in The Ticket, which “shifts one half one text and half the other through a page frame on conveyor belts.” On the other hand, while the results were still uneven, the many hundreds of archival draft pages prove how hard Burroughs worked to make the cut-up machine serve his writing.

In a 1960s context his methods resemble those of Pop Art, and The Ticket references James Dean and the recently dead Marilyn Monroe, while for Nova Express Burroughs felt a “pop art cover is definitely indicated.”7 But the cut-up text both parallels the mechanical genius of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen factory and exceeds it. Whether using fragments of Rimbaud or old song lyrics, The Ticket demonstrates a manipulation of material whose precision has never been recognized. The book’s original title, “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair,” is a representative case, the nursery rhyme ballad condensing a complex intertextual network that shows how signs get around on what Burroughs called “association lines.” It takes a while to realize it, but in training us how to read his text—which all experimental writing has to do—Burroughs is training us how to read the culture around us, or rather the culture inside us.

Just two words of “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” occur a single time in The Ticket: “the fair.” Is this really an allusion? It’s ambiguous since what fascinated Burroughs and in turn makes his own work so fascinating is the subliminal or contingent message, communication that slips beneath consciousness or seems to arise by chance from the material itself. In broad cultural terms, he promoted cut-up methods as strategies of détournement, as the Situationists called their contemporaneous response to the emerging “Society of the Spectacle,” the all-pervasive sign systems of the news media and consumer capitalism. Burroughs’ didactic political writing often made explicit calls to action, as in one early 1960 typescript: “TEAR THEIR ADVERTISEMENTS FROM WALLS AND SUBWAYS OF THE WORLD.”8 Such direct statements were necessary because his creative counter-measures were, by definition, experimentally indeterminate: the results of writing with scissors were impossible to predict and exemplary in function, opening up new possibilities rather than serving fixed outcomes. Burroughs therefore identified his methods with asymmetrical warfare rather than political programs—The Ticket cites part of Mao’s formula for guerrilla tactics (“Enemy advance we retreat”)—and he categorically differentiated his methods from those of commercial advertising: “I’m concerned with the precise manipulation of word and image to create an action,” he told an interviewer in 1965, “not to go out and buy a Coca-Cola, but to create an alteration in the reader’s consciousness.”9

In this context, “the fair” is a necessarily ambiguous sign. In fact, even if it is recognized as a subliminal trace of lyrics, a molecule of music, the ambiguity of the allusion remains: since there are two mentions of the city’s name in the same paragraph, the “fair” must also reference the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. That fair inspired another song, “Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis,” and forty years later the Hollywood film directed by Vincente Minnelli. Located in the city of Burroughs’ birth—which is named over twenty times in The Ticket—the St. Louis World’s Fair was famous for its 265-foot-high Ferris wheel, and such wheels return repeatedly in The Ticket, their rotary motion coinciding with the circularity of the songs’ lyrics. Because “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” and “Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis” share the same theme—the broken promises of desire—as well as the same seductive sign of “the fair”—the merry carousel of capitalism—it perhaps doesn’t matter whether Burroughs was referring to Johnny or Louis, but a cut-up source typescript confirms it was actually both: “Oh oh what can the matter be, John?—Our revels now are ended—These our actors at St Louie Louie meet me at spirits and are melted into air.”10 Mixing in the two song titles with Prospero’s great speech from The Tempest, Burroughs turns Shakespeare’s valediction to stage magic into a farewell to the fair.

These unused lines from the manuscript also confirm Burroughs’ working methods in The Ticket, specifically his editorial process of redaction, as he cut and re-cut his source materials to make the external referential function of words ever more cryptic. However, once we’ve learned to read on lines of association and juxtaposition, the accumulation of allusions makes his larger theme clear enough. Whichever way we identify “the fair,” as a musical or historical reference, the cut-up method makes the words operate in a chain of internal cross-referencing that recycles the genetic code of the Burroughs oeuvre from text to text.

At the end of Naked Lunch there’s a passing, enigmatic allusion to one person watching another while “humming over and over ‘Johnny’s So Long at the Fair,’” and in 1960 Irving Rosenthal asked Burroughs about it as he helped edit the book for its American publication: “Come now Irving,” Burroughs replied. “You have heard that tune a thousand times. We all have.”11 Rosenthal seemed to have forgotten not only the song from childhood but also that the opening of Naked Lunch had set it up and implied its significance. Early on Burroughs introduces a drug pusher who “walks around humming a tune and everybody he passes takes it up,” peddling such songs as “Smiles” or “I’m in the Mood for Love” (both of which appear in The Ticket). A drug in itself, the music of love is used to sell other drugs, and this nexus of addiction, contagion, subliminal advertising and brainwashing through popular culture is captured in the seemingly mundane act of humming a tune. As the original title of what became The Ticket That Exploded, “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” signifies both the enduring pain of personal loss—nostalgically for childhood innocence, melancholically for love—and its manipulation according to the false promises and addictive kicks of consumer capitalism. “O dear, what can the matter be?” Johnny’s so long at the fair because, like a hypnotized chicken, he’s been hooked.

The intertextual thread of the fair leads back from The Ticket via Naked Lunch to Burroughs’ early novel, Queer, a vital point of origin for both biographical and aesthetic reasons. Here, it’s the sinister Skip Tracer, a psychic Repo Man dreamed up by William Lee to track down Eugene Allerton, the lover that has abandoned him, who “begins humming ‘Johnny’s So Long at the Fair’ over and over.”12 Again, it’s “over and over,” implying that the desire and the pain will never be over. His first novel, Junky, describes Burroughs on drugs, but the writing of Queer shows him hooked by desire, which makes it more essential to the oeuvre that followed. Indeed, despite the gulf between early autobiographical novella and radical experimental text, Queer predicts The Ticket at a precise formal level. It does so by embedding the menacing song in passages of recurrent images and phrases, including the sound of humming, which create uncanny effects of déjà vu. This eerily repetitious textuality becomes the very hallmark of Burroughs’ writing from Queer onward, and it’s no coincidence that for the 1967 edition of The Ticket Burroughs created a new opening section that recycled the narrative of Queer.

The narrative Burroughs added to The Ticket replayed the “possession” of Lee by Allerton and is crucial because it retrospectively grounds the cut-up text in Burroughs’ experience of traumatic desire. The link confirms that his research into the virus of language was less “experimental writing” than scientific self-experimentation. The reduction of “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” in Queer to “the fair” in The Ticket cuts up the song’s refrain to separate Johnny from the fair, as if surgically removing a tumor of lovesickness. Since late 1959, when his discovery of cut-up methods coincided with a dramatic break from psychoanalysis and his adoption of Scientology techniques for erasing traumas, Burroughs’ logic had been that our consciousness and sense of reality are verbally programmed from without, so reversing the mechanistic process should lead to deconditioning: “Get it out of your head and into the machines.” Making trauma into a text, the cut-up method was one such machine and the tape recorder its obvious technological extension. But on the evidence of The Ticket, the actual results were mixed or, as Alan Ansen suggested, quite paradoxical: “Are not cut-up and fold-in the music of obsession, fragments that evoke rather than destroy?”13

On the one hand, the text achieves its own self-ruination and the result is page after page of mechanically atomized prose: a “disastrous success,” to borrow Burroughs’ own ironic warning. More interestingly, the text that explodes gives rise to “tentative beings,” “flicker ghosts,” and cybernetic aliens that spin “free of human coordinates” to reveal hybrid creatures with bodies “of a hard green substance like flexible jade—back brain and spine burned with blue sparks as messages crackled in and out.” Applying a similarly post-human aesthetic to music lyrics, The Ticket produces monstrous human-machine composites out of the charming “Daisy Bell” (“love skin on a bicycle built for two,” “i’m half crazy all for the love of color circuits”). Burroughs was writing this in 1962, the same year that a physicist at Bell Labs synthesized the very same song on the vocoder of an IBM 704 to demonstrate the first singing computer. When HAL sings “Daisy Bell” while being disconnected in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (released in 1968, a year after the revised Ticket), the pathos of the dying machine seems to mock our belief in human subjectivity, memory and emotion. For as capitalist technology makes our machines smarter and softer, so we come to appear more stupid and automated. Individual identity is reduced to the effects of a mechanical device, repeating like the roll of music in a player piano or vinyl going round on a turntable—as Burroughs suggests in a mid-1960s text courtesy of lyrics from Irving Berlin’s “The Song Is Ended”: “but the melody lingers on . . . but the melody lingers on . . . but the melody lingers on . . .”14

On the other hand, a ghost remains in the Burroughs machine, a poetic lyricism and a humanity that is all the more deeply felt and mourned for being so surprising: “sad shadow whistles cross a distant sky . . . adiós marks this long ago address . . .” The Ticket succeeds above all in such elegiac gestures of farewell, its paradoxically memorable enactments of forgetting, especially in the last pages: “I lost him long ago . . . dying there . . . light went out . . . my film ends.” With a shocking pathos worthy of this flawed but fascinating book, when Burroughs died in August 1997, Patti Smith attended the funeral at Bellefontaine cemetery in St. Louis and did a graveside rendition of . . . “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair.”

This valedictory quality is particularly fitting because, contrary to the standard history, The Ticket That Exploded was not the middle volume of Burroughs’ Cut-Up Trilogy, following The Soft Machine and preceding Nova Express; it was the final one.

THE TICKET MACHINE

The Soft Machine, Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded have been grouped together for fifty years. This is partly because they are so unlike anything else and partly because the identity of each book is blurred by Burroughs’ recycling of material across and between them. And yet, although the term is impossible to avoid, “the Cut-Up Trilogy” was always a misnomer. This is because Burroughs never planned to write a series of three books and didn’t himself use the term, and because calling them “the trilogy” has the effect of domesticating these wildly experimental texts and glossing over the differences between them. But equally, it’s because over a seven-year period this “trilogy” materialized itself as no fewer than six quite different books: three versions of The Soft Machine (1961, 1966, 1968); two of The Ticket That Exploded (1962, 1967); and one of Nova Express (1964). Given the publication dates, it’s possible to generate half a dozen sequences that would form “trilogies.” Burroughs made a joke out of the resulting confusion, referring in the 1966 edition of The Soft Machine to “a novel I hadn’t written called The Soft Ticket,” and the gag itself could be permutated from The Nova Machine to The Express That Exploded. The consequences for interpretation have been serious, however, since critics need to map the development of his work using a beginning, middle and end to “the trilogy,” and, lacking the chronology or muddling up the editions, misread the texts accordingly.

In practice, this multiplicity has been conveniently concealed by being reduced to simply “the trilogy” in a single order: first The Soft Machine, then The Ticket That Exploded, finally Nova Express. Since this order follows the sequence of first publications of each title, it appears logical, but it’s false at both a material and philosophical level: materially, because the differences between editions of the same title are significant; and philosophically, because “the trilogy” represents exactly the false essentializing linguistic usage against which Burroughs deployed cut-up methods in the first place—put most succinctly in his attack on the definite article in Nova Express: “Alien Word ‘the.’ ‘The’ word of Alien Enemy imprisons ‘thee’ in Time.” Burroughs’ revisions of “the trilogy” over time were contingent and materially motivated, arising from a tension between his creative methods and the nature of book publication, but they certainly served the philosophical goal of scrambling traditional notions of fixed identity and linear chronology.

The standard sequence is also misleading in entirely practical terms of available editions. In June 1961 Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press in Paris published The Soft Machine, followed eighteen months later by The Ticket That Exploded. Like the original Olympia edition of Naked Lunch, which appeared in July 1959,15 these were physically small softback books wrapped in distinctive olive green papers and artwork dust jackets (with designs by Burroughs himself, then Gysin, and finally Sommerville). In addition to having a very special look and feel as physical objects, the Olympia trilogy has become eminently collectible, and the two cut-up volumes are especially rare because, after the initial print run of 5,000, they were never republished. For almost all their history as titles, therefore, the available editions of both The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded have not been the original books but the later revised versions—each of which were published after Nova Express, the supposedly final title of the trilogy. Leaving aside the Calder 1968 British edition of The Soft Machine, the Grove Press Ticket was therefore the final text of “the trilogy,” since it appeared after both the Grove Nova Express (1964) and Soft Machine (1966). But this deals only with histories of publication, whereas the most revealing history affecting how we read The Ticket That Exploded is that of composition.

Since The Ticket was first published in 1962 and Nova Express in 1964, the general assumption has always been that Burroughs wrote The Ticket long before Nova Express, but this is not the case. Following the appearance of The Soft Machine in summer 1961, Burroughs began work on Nova Express that August, and by the end of March 1962 had mailed a full manuscript to Barney Rosset at Grove Press. Although he would submit a revised manuscript in October 1962 and continue to make changes up until July 1964, nevertheless the great majority of the book published as Nova Express in November 1964 had been written by March 1962. Burroughs’ first reference to what would become The Ticket That Exploded—informing Rosset, “I am currently working on a new novel” (ROW, 106)16—does not appear until late June 1962, and although he must have started it the previous month, this still confirms that The Ticket was not even begun until at least a month after the first draft of Nova Express was finished. And so while the history of publication invites us to think of The Ticket as preceding Nova Express by two full years, the history of composition tells us to see it as following straight after.

Then again, since almost all readers of The Ticket only know the revised edition of 1967, to understand how the parts of Burroughs’ trilogy relate to one another we need to know the writing history of not one but two versions of the text—even as one of the results of the trilogy is to call into question our very concept of “version” or “original.”

“WHAT AM I AN OCTOPUS?”

While he refers to it as a “short piece” rather than as part of his new novel, Burroughs first mentions material destined for The Ticket in a letter to Paul Bowles sent from the Beat Hotel in mid-May 1962.17 Titled “East Clinic Information,” it formed the start of the “vaudeville voices” section, although what’s most revealing is not the material Burroughs began with but the method: “Using the fold in technique more and more, results usually interesting if sometimes cryptic.” As Burroughs implies, he had already been folding rather than cutting his material for some time, and had in fact hung up his scissors almost three months earlier. The significance of this change in method is to separate The Ticket from The Soft Machine and Nova Express, both of which were begun (although not in the latter case completed) using his original cut-up technique. In contrast, The Ticket was a fold-in from the start.

As for the method itself, Burroughs gave the fullest descriptions in his talk “The Future of the Novel” at the Edinburgh International Writers’ Conference in August 1962, an event that was a turning point for his reputation, and as a Note published with a longer version of “vaudeville voices”: “In writing this chapter,” he begins, “I have used what I call ‘the fold in’ method that is I place a page of one text folded down the middle on a page of another text (my own or someone else’s)—The composite text is read across half from one text and half from the other—The resulting material is edited, rearranged, and deleted as in any other form of composition.”18 In private letters and in published statements such as this, Burroughs would repeatedly stress not the radical difference of his compositional methods but their similarity to others in respect of editing. This was a strategic counter to those who accused him of lazily producing haphazard nonsense, like the famous “UGH” reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement who in 1963 derisively compared his work to “the unplanned dribbling and splashing of the action painter.”19 Likewise, the review in Time magazine in November 1962 dismissed the fold-in method for taking pages of “newspaper, Shakespeare, or whatnot” and sticking them together “at random,” so that The Ticket “came daringly close to utter babble.”20 Burroughs’ counterattack included cutting up both hostile reviews, a ritualistic act of revenge that produced new material for the 1967 edition of the book in which he mocked Time’s own mocking phrases. But just as importantly, his insistence on exercising artistic control through careful editing responded to those who praised him for his techniques, including his own publishers.

In particular, Burroughs must surely have been frustrated by John Calder—as staunch a supporter of his work in London as Girodias in Paris or Rosset in New York—for the jacket blurb on Dead Fingers Talk. Published in Britain in 1963, this composite trilogy, made from selections of Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine and a good deal of The Ticket That Exploded,21 hailed Burroughs’ style as having “much in common with American action painting.” Around this time Burroughs drafted a defense of his methods, insisting “I am not an action writer whatever that may mean.”22 “The procedure,” he explained, “is not arbitrary but rather directed toward obtaining comprehensible and useable material—There is careful selection of the material used and even more careful selection of the material finally used in the narrative.” On the other hand, the comment he made in September 1962 when submitting his manuscript of The Ticket—“Find myself returning to straight narrative style of Naked Lunch” (ROW, 114)—suggests the problem he had lost sight of, since Naked Lunch is nobody else’s idea of a straight narrative.

The other problem with Burroughs’ experimental methods, and one of the difficulties they pose for anyone discussing them, is that there is no typical cut-up text or, within a book like The Ticket, even a typical cut-up section: he used multiple methods with multiple results and made multiple claims for their function—creative, political, therapeutic, scientific, even mystical (“Table tapping? Perhaps”).23 Burroughs used cut-ups for “poetic bridge work” and as a “fact assessing instrument” (ROW, 45), and the only common denominator was that his methods were neither random nor indiscriminate but driven by an empiricist’s sense of curiosity. Burroughs prized cut-up and fold-in techniques as ways to make discoveries that exceeded the predictable reach of the rational mind, so that the material itself led him to discover meanings and make connections. The Ticket illustrates Burroughs’ creative procedures through its blurring of distinctions between poetic fantasy and scientific fact and its equation of textual body with human body—pointing to the book’s origins as a testing of limits in terms of publishable form and content.

When Burroughs informed Barney Rosset that he was working on a “new novel” in June 1962, he specified that he was pushing the limits precisely in terms of the text’s most recurrent word, the body: “I am elaborating some far out areas with scenes and concepts more ‘obscene’ than anything in Naked Lunch or The Soft Machine,” he explained; “I was interested to carry certain concepts to the furthest possible limits as an experiment in writing technique” (ROW, 106). A thesis regarding sexual repression was essential to his analysis of power in his new book—“Now do you understand who Johnny Yen is? The Boy-Girl Other Half striptease God of sexual frustration”—and was implicit in The Ticket’s alternative working titles “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” and “If You Can’t Say It Sing It” (108). Openly homosexual, Burroughs in the early 1960s was at the forefront of enlarging the scope of what could be said, and Grove Press’s publication of Naked Lunch in 1962 duly became a legal and cultural landmark in that history.

The Ticket has more orgasms and penises than The Soft Machine and Nova Express put together and its descriptions of alien sex are perversely poetic, but Burroughs seems to have emphasized how sexually far out his new book was in order to deter Grove Press. Although he asked Rosset in June if he wanted to see the “thirty or forty pages” he had already written, and although the editor’s autograph note on the received copy states “yes very much,” Burroughs was already in negotiations with Maurice Girodias.24 And unlike Rosset, who was still anxiously holding back Naked Lunch (keeping copies locked in the warehouse until November 1962), Girodias had no fear of obscenity trials in Paris for publishing an English language book. Whereas Burroughs worked on Nova Express throughout 1962 expecting it to help pave the way for Grove to publish Naked Lunch, he wrote The Ticket for Olympia without worrying about its sexual, censorable content.

Burroughs composed The Ticket at almost twice the pace of Nova Express, which had taken eight months. At the start of July 1962 he announced he had already “half finished” the novel, which he “wrote at the rate of ten pages a day while writing a film scenario with the other hands, making recordings.”25 The rapid progress of The Ticket reflected Burroughs’ shift from cutting to folding, a quicker, far less messy procedure. Connecting the speed of writing to his experimental work in audio and visual media, Burroughs also echoed comments he had made eighteen months earlier that The Soft Machine “writes itself” and was “more like taking a film” than writing; “But why draw lines and categories?” (ROW, 65). Like the Dadaists and Surrealists before him, Burroughs found that collage-based methods effaced traditional distinctions between media, and what started with paper and scissors ended up turning the writer into a poly-practitioner—working a typewriter with one hand, a tape recorder with the other, and a movie camera . . . “What am I an octopus?” Burroughs liked to ask.

The verbal-visual relationship was especially important for The Ticket, and as soon as he had finished writing the final section in mid-August 1962, Burroughs mailed the 3-page typescript to Brion Gysin and invited him to complete the text as a physical object: “I would like to end it with a page of calligraphs to follow after the last lines—‘Silence to say good bye’—Could you do like some terminal writing and send along so i can finish the novel like that?”26 For all his notorious shortcomings as a businessman, Girodias always let Burroughs define the artwork for his Olympia titles, and he agreed that Gysin’s art “would be the best ending” for The Ticket—although at this point the title was still not fixed (ROW, 112). Indeed, Burroughs seems to have dropped “Johnny’s So Long at the Fair” and taken up “Word Falling—Photo Falling” before, in late September 1962, for the very first time he refers to it as The Ticket That Exploded.27 That same month he submitted a 132-page typescript and the book was launched in the English Bookshop at the start of December. Shortly after, Burroughs left Paris and the famous Beat Hotel—which on and off for three years had been Cut-Up Headquarters—closed down. It was the end of an era, but the end of only the first of two Tickets.

“A COMMENTARY AND EXTENSION”

When Burroughs informed Paul Bowles that The Ticket was about to be published, he mused: “Perhaps I have said what I had to say—Hope so at any rate.”28 Despite the air of optimism and finality, just two months later the seeds of a new edition were already being planted. In January 1963 he asked Alan Ansen for his opinion while making clear his own: “I am not altogether satisfied with it.”29 This was how Burroughs reacted to every version of his cut-up books, and for the same reason: there was always a kernel of contradiction between his methods and book publication. Even before Naked Lunch was finished in 1959, Burroughs had come to “wonder if any writing now has much raison d’être,” and the impact of Gysin’s painting and calligraphy led him further to query the codex form.30 His subsequent experiments with drawing, scrapbooks, tape recorders, film, photography and photomontage fed into his writing but also confirmed the limitations of texts. At least the little magazines of the 1960s mimeograph revolution allowed variety in typography and layout—such as newspaper-style three-column pieces—while the rougher aesthetic of some magazines well represented the provisional, process-based nature of his mass of short experimental work. In contrast, the book was an old technology that depended on publishing houses with limited formal options and fixed procedures for copyediting and printing. Burroughs was bound to be dissatisfied.

In his January 1963 letter to Ansen, Burroughs explained that the need for revision had come to him when assembling Dead Fingers Talk: “While doing this job of selecting and rearranging I became so dissatisfied with The Soft Machine that I have completely rewritten it.”31 Two years later, he confirmed that The Ticket would be next for Operation Rewrite: “It’s not a book I’m satisfied with in its present form. If it’s published in the United States, I would have to rewrite it.”32 Burroughs made no move to revise The Ticket until summer 1966, when Richard Seaver at Grove Press reminded him that they would need to publish any new version “by early 1967 in order to keep the copyright.”33 As a determining factor in revising the book, this was a nice irony, given The Ticket’s recycling of cultural materials and therefore assault on concepts of originality and ownership. The timing for Burroughs was difficult, however, and in mid-October he appealed to Seaver for patience on delivering the manuscript. In a decade of being constantly on the move, living out of suitcases between London, Paris, New York and Tangier, this was the first time he struggled to meet a deadline. Although Burroughs demonstrated a remarkably consistent responsibility toward his publishers, he also did not want to be rushed by Grove on The Ticket; he surely hadn’t forgotten his intense frustration over their editing of The Soft Machine a year earlier, when Seaver (not unreasonably) had called a halt to his making revisions. Equally, the economic realities of his writing career were not his strong suit. “I hope that you feel as I do,” he wrote on October 26, 1966, the day after finally mailing the manuscript, “that it is now a much more readable and saleable book.”34 The fact that the print run of the revised Ticket, published in June 1967, was barely half that of the revised Soft Machine, published by Grove in March 1966, suggests they knew it was not going to be a bestseller.

There are four main areas of difference between the Olympia edition of 1962 and the Grove revised version of 1967: without altering the sequence of material in any way, Burroughs made cuts, additions, changes to presentation and to the ending of the text. First, he made some forty-three separate cuts—many as small as a single phrase—so that in total the revised edition lost just over 400 words of the Olympia text. Why these particular cuts were made is not at all clear, and in several cases the loss is certainly meaningful, so they have been restored for this new edition. Second, there was the addition of new material written over the previous three years, parts of which had appeared in little magazines in 1964 and 1965. There were nineteen separate insertions, ranging in length from ten to 4,500 words, so that, including “the invisible generation” appendix, in total the 1967 edition was 50 percent longer than the original (rising from just over 40,000 to 60,000 words). The addition of “the invisible generation” reflected Burroughs’ sense that his tape recorder experiments were being enthusiastically taken up, and yet his pitch of the essay to Seaver was tentative—“If the book is not yet set up, this piece could be used to advantage as an appendix”—and the editor probably didn’t realize that a quarter of the 3,500-word article had already been added to The Ticket.35

Burroughs’ plan to make the new book more “readable” did not, therefore, entail deleting cut-up material to any meaningful extent, and indeed a fifth of what he added was also cut-up, so that the overall change was modest: just over half the 1962 text consists of cut-up, just under half of the 1967 text, although the impossibility of defining what is and isn’t “cut-up” (or “fold-in”) makes more precise calculations meaningless. Of the book’s twenty sections, only the first (“see the action, B.J.?”) was entirely added for the 1967 edition, eleven sections remained exactly the same, and eight were expanded. Of those eight, the first and last sections of the original book (“winds of time” and “silence to say good bye”) were expanded by far the most, so that the impact of Burroughs’ revisions was heavily concentrated on the beginning and ending. Although they include some of the funniest passages in the book, the additions he made to the final section created a structural problem, since The Ticket was already long enough and it was surely a mistake to introduce so much new material so late on. Burroughs needed novel-length books in order for his methods to produce uncanny flashes of déjà vu in the reading experience—a unique and beautifully disorientating sensation—but there was a point of diminishing returns and in The Ticket he probably reached it.

All Burroughs’ cuts and insertions are documented in the Notes section, which also gives details of editorial changes involving about a hundred minor corrections and includes significant selections from the major archival variants. The aim is not only to show exactly how Burroughs updated The Ticket and to carry out some necessary restorations but to make visible for the first time the bigger picture of the manuscript sequences from which the published text was cut.

The 1967 Grove jacket blurb rightly observed that “the new material serves both as an expansion of and as a commentary on the original,” and this is clear from the very first insert, in the “winds of time” section. The new writing declares its status by looking back at the original edition, commenting on the opening two pages: “That was in 1962.” The material was explicitly self-reflexive (“I am reading a science fiction book called The Ticket That Exploded,” says the narrator of the opening section)—but not only in terms of content. What’s striking about Grove’s jacket blurb is that it precisely echoed how Burroughs himself had described the formal appearance he wanted for his text: “The new material added to The Ticket That Exploded has been spliced into the original text,” he explained to Marilyn Meeker at the publishing house; “In this new material I have as you notice used slightly different punctuation and I think that this altered punctuation should remain so that the splice ins will be apparent forming as it were a commentary and extension of the text.”36 Recognizing the tendency of editors to regularize, Burroughs sounds cautious, but he took very seriously the visual impact of orthography on the page, which is the third major difference between Olympia and Grove editions.

To begin with, the biggest change was not actually made by newly added material but by alterations to the original text. In particular, Burroughs revised to lower case many hundreds of upper-case letters, removing capitals from the first person (“I” became “i”) and from words at the start of sentences or in specific phrases (“Nova Police” became “nova police,” “Board Books” became “board books,” and so on). The result is a lack of consistency that at first strikes the reader as a series of errors, then as a challenge to discover a principle, and finally as an indeterminable system that can only be accepted for what it is. Since it’s part of Burroughs’ critique of literary and linguistic conventions, from an editorial point of view the whole concept of error and intentionality is put into question and the only certainty is that it would be a mistake to impose consistency. On the other hand, nor should the past errors of copyeditors, printers, or Burroughs himself be fetishized as if there were a degree zero of editing. It’s not just that “Harly St” should become “Harley St” or “Gothenberg” “Gothenburg,” but that “hassan i sabbah” should be “Hassan i Sabbah” since the name was only put in all lower case when Grove misinterpreted Burroughs’ request to change block capitals from the first edition (including at one point “HASSAN I SABBAH”) into lower-case italics. Burroughs was a poor proofreader but the archival evidence shows he neither passively accepted nor actively embraced mistakes at the editorial stage.

More coherently, Burroughs extended his experimentation with punctuation, which went back to the use of parentheses and ellipses in Naked Lunch. Like Nova Express, but unlike The Soft Machine, the 1962 text of The Ticket had used the em dash ( — ) as radically as one of Burroughs’ major influences, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, had used the ellipsis (. . .). The Olympia edition of The Ticket had just a single three-dot ellipsis but some four thousand em dashes which function, as the French novelist said in the mid-1950s of his own punctuation, like the rail tracks on which the metro of the writing depends. But just as Céline surprisingly made the ellipsis, normally a sign of suggestion and enigma, the electric dynamo of prose that “charges right into the nervous system,” so the surprise of The Ticket is to find the dash used for more than a sense of urgency.37 Burroughs never explicitly theorized punctuation as Céline did, but he was well aware that the material he added in 1967, containing some four hundred two-dot ellipses, a dozen three-dot ellipses, and about a hundred more em dashes, transformed the page. All these dots and dashes make the entire text of The Ticket an encrypted signal, a code or “system,” as one draft typescript puts it, “like Morse with scales of intensity and speed.”38 Because they cannot be spoken aloud or put into words, the em dashes and ellipses are crucial to the physical sensation of the reading experience, but Burroughs’ practice was more than a generalized aesthetic. On the contrary, on close inspection The Ticket shows how subtle and precise his use of a dash was in literary terms. Take the example of the section “combat troops in the area.”

The first half of “combat troops” appeared in the 1962 edition, shown in its use of the em dash some 250 times, an average of every ten words. The second half of the section, added in 1967, has only a single em dash and the main punctuation is the two-dot ellipsis, of which there are more than seventy. The placement of the one em dash—so visibly out of place in a paragraph sprayed with a dozen ellipses—is carefully contrived in lines that refer to the experimental poet e.e. cummings: “his gentle precise fingers on Bill’s shoulder fold sweet etcetera to bed — EE Cummings if my memory serves and what have I my friend to give you? Monkey bones of eddie and bill?” The obvious anomaly is that Burroughs puts the poet’s name in upper case, rather than using the lower-case letters that exemplified cummings’ famously nonstandard orthography. This is the tip-off to three more subtle manipulations. First, there’s the title of cummings’ poem “my sweet old etcetera,” which Burroughs alters by inverting the word order and turning “old” into “fold” to make a self-reflexive pun on his fold-in method. Second, the phrase “eddie and bill” has also been subject to a precise restructuring, since Burroughs has separated the run-together names “eddieandbill” from another cummings poem. Finally, and not by chance, this other poem has an em dash in its very title: “in Just—” Although it’s easily missed, Burroughs has named the second poem just through his use of the dash, and encoded his work in a tradition of typographic poetic experiment.

Such precision at the microscopic level demonstrates an attention to detail for which Burroughs is almost never given credit. It also suggests why it is necessary to edit The Ticket with rigor, and the Notes section provides textual and archival evidence in support of changes made or, in the case of certain apparent errors, not made. However, the text was also determined by more contingent circumstances at the formal level, by chance factors that pose a different challenge to the editor, as they do to the reader and literary critic. Out of all Olympia and Grove Press editions of the trilogy, The Ticket is actually the odd one out in its use of the em dash, for here the dash is printed with a space on either side; a small difference, but one that makes a definite impact on the look of the page and therefore the experience of reading. Since the question of agency is central to the text and the method of its production, we have to ask: was this intentional? The answer is in the typesetting manuscript Burroughs submitted to Olympia Press in September 1962. The first forty-four pages have the spaced em dash, which seems to have invited the typesetters to follow suit. The remaining two thirds of the manuscript, however, uses Burroughs’ standard dash without spacing, and comparison of the two parts establishes that the first third was typed not by Burroughs but for him. On its own, such evidence is inconclusive, but Burroughs’ intentions are confirmed in the Olympia page proofs—the final stage before printing—which include his last-minute addition of a typed insert, a paragraph using more than a dozen of his standard em dashes, without spacing.39 Letting the spaced em dashes stand for the 1967 Grove edition, Burroughs in effect granted the material its own agency, tacitly recognizing that texts are collaborative and that the work has a life of its own independent of the supposed author. The most important collaboration between design and contingency in the production of the two Tickets, and the final major difference between editions, concerns the very end of the text.

“SILENCE TO SAY GOOD-BYE —

In 1962, Burroughs asked Gysin to produce some “terminal writing” in order to solve the problem of ending a book that subverted the linearity of traditional narrative. Gysin’s calligraphy terminates the text physically by permutating in pen the section title—“silence to say good bye”—turning typed words into graphic forms and changing words that can be spoken into silent shapes. By canceling the referential function of the sign, the calligraphic line puts an end to the voice and the illusionism of realist language. In this way Gysin’s terminal writing is a perfect complement to the final section’s invocation of The Tempest: “These our actors bid you a long last good bye.” As the text’s characters line up to bid adieu like performers on a stage, they now appear as just characters—merely typographic signs on sheets of paper, their voices only words inside speech marks. Theme and form coincide in terms of simultaneously inscribing and unraveling identity. Thematically, it was all a masque, and we are such stuff as dreams are made on. Formally, in making the transition from anonymous print to artist’s pen—and we notice that Gysin signs with his initials—the calligraphy echoes the unexpected switching of type and script on the Olympia Press jacket cover. There, beneath Sommerville’s photo-collage, the book title is written in large red ink in Burroughs’ own distinctive script above his name, while his name is not signed by hand but perversely typed in black block capitals. The cover by Kuhlman Associates for Grove in 1967 was also typographically striking, producing various letters out of a hat that seems to belong to Charlie Chaplin, but neither the comic tone nor the Dada-esque design has anything to do with the artwork inside the book or with questions of authorship and identity.40

The final feature that makes the ending of the Olympia edition so intriguing is the precise transition between Burroughs’ text and Gysin’s drawing. The transition not only silences language but spatializes time, as the temporal march of words from left to right gives way to a spatial arrangement. This farewell to Time draws attention to what lies beyond words literally on the page, as the 1962 Ticket ends with the word “good-bye —” hyphenated and split at the end of the line, so that all six lines of text on the final page end with either an em dash or a hyphen:

tain wind of Saturn in the morning sky —

From the death trauma weary good-bye then” —

Hassan i Sabbah: “Last round over —

Remember i was the ship gives no flesh ident-

ity — Lips fading — Silence to say good-

bye —

The effect of these solid lines one above the other is to resemble the first hexagram of the I Ching—Ch’ien (The Creative), made up of repeated trigrams for “Heaven.” Burroughs and Gysin were familiar with how the ancient Chinese system of divination had been used as a method of chance composition—most famously in music by John Cage since the 1950s—and because nowhere else in The Ticket are so many horizontal lines stacked like this, the ending seems to simultaneously identify the creative principle of the text and abandon it in a single gesture. Significantly, the text’s one-word final line ends without any closing speech marks, so that the last em dash points with a straight line into empty space. Immediately below this final line, Gysin’s script and calligraphy begin, the right side of which ends with a series of horizontal lines paralleling the printed em dashes and hyphens of the typed text above it, so creating a second potential hexagram. However, the most important element is simply that Gysin’s calligraphy is reproduced beneath the last typed words on the same page, which is also the final leaf in the book. The closer you analyze it, the more perfect the fusion of type and script seems to become. But again, was any of this intentional?

On the last page of his 1962 typesetting manuscript Burroughs signaled his attention to visual detail by typing, rather than his usual two dashes, five dashes after the final word “good-bye,” indicating his aim to end with an especially elongated line. The archival record also shows that the key feature of the Olympia Press design—the printing of Gysin’s artwork immediately after his text to form a single and complete last page—was not some happy accident. On the contrary, an editor at Olympia put a note on the penultimate sheet of the page proofs requesting that lines of text be moved precisely in order to make this happen: “faire passer au moins 4 ou 5 lignes à la p. 183.”41 As regards the actual layout of text on the last page of the Olympia edition, with its striking line-up of dashes and hyphens, there’s no evidence to suggest that this was determined by anything more than the number of words and the narrow line width. In which case, the hexagram of lines for Heaven was the product of a material accident, which is entirely fitting given the role of chance in the philosophy and practice of both the I Ching and cut-up methods. We are left not with a choice between meaningful creativity or meaningless mysticism but with a way of reading beyond the binary of belief and skepticism.

The 1967 Grove Press edition dramatically changed the book’s ending. The addition of new material made the last section five times longer, while the final paragraph shifted the tone and created a sense of circularity by echoing lines of speech from the book’s opening section. The last paragraph also ended with a new final phrase, closed by speech marks: “Are you listening B.J.?’” The typed words were now separated off from Gysin’s script, which, in the most radical change, was reproduced on the facing leaf. And finally, this was no longer the final leaf in the book, since it was followed by “the invisible generation” Appendix, a text without punctuation that concluded with words from The Tempest (“into air into thin air”) followed by empty silent space.

In different ways, the Olympia and Grove editions of The Ticket created complex open endings, and given the book’s project to transcend time, it would be ironic to fetishize the past and deny change by repeating the products of particular historical circumstances. This edition ends by making choices that point in contrary directions—cutting “the invisible generation” essay as an appendix of historical interest (key passages are referenced in the Notes; the full text is available elsewhere)42 and restoring the integration of Gysin’s calligraphy as the book’s great transcendent gesture. After all the lyrics and melodies in The Ticket, all the “vaudeville voices,” “riot noises,” “sounds of lovemaking,” “City sounds,” “jungle sounds,” “crackling static,” and “sound of feedback,” the composite formed by print and script ends the most musical book of the Cut-Up Trilogy on a soundless note. The book silences the noisy lusts of life, stops the fairground circus that stupidly spins us round and around, and takes its leave with an open-ended vision of an elsewhere. A book of paradoxes—cynical yet elegiac, polemical but poetic, obscene and spiritual—The Ticket ends by visualizing silence, a vital space of possibility beyond words, “where the unknown past and the emergent future meet in a vibrating soundless hum.”43

Oliver Harris

July 1, 2013

1. Burroughs to Gysin, July 26, 1960 (William S. Burroughs Papers, 1951–1972, The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library, 85.2; after, abbreviated to Berg).

2. Burroughs “Voices in Your Head,” introduction to You Got to Burn to Shine, by John Giorno (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1994), 6.

3. Undated typescript, circa 1960, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

4. Iggy Pop interviewed by David Fricke in Rolling Stone (April 19, 2007), 59.

5. Brion Gysin in Minutes to Go, by Sinclair Beiles, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Brion Gysin (Paris: Two Cities Editions, 1960), 5.

6. Burroughs to Gysin, October 25, 1966 (Berg 86.9).

7. Burroughs to Seaver, July 21, 1964 (Berg 75.1).

8. Undated typescript, circa 1960 (Berg 48.22).

9. Burroughs Live: The Collected Interviews of William S. Burroughs, 1960–1996, edited by Sylvère Lotringer (New York: Semiotext(e): 2000), 80.

10. Undated typescript, circa 1962 (Berg 20.50).

11. Burroughs, Naked Lunch: the Restored Text, edited by James Grauerholz and Barry Miles (New York: Grove, 2003), 194, 251. For the definitive study of musical references in the text, see Ian MacFadyen’s “A Little Night Music” in Naked Lunch@50: Anniversary Essays (Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2009).

12. Burroughs, Queer: 25th Anniversary Edition (New York: Penguin, 2010), 118.

13. Alan Ansen, William Burroughs (Sudbury: Water Row Press, 1986), 22.

14. Burroughs, “The Dead Star,” My Own Mag 13 (August 1965), 12.

15. The Olympia edition was published as The Naked Lunch, with the definite article, as were British editions.

16. Rub Out the Words: The Letters of William S. Burroughs, 1959–1974, edited by Bill Morgan (New York: Ecco, 2012), 106. After, abbreviated to ROW.

17. Burroughs to Bowles, May 20, 1962 (Paul Bowles Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin; 8.10). After, abbreviated to HRC.

18. Burroughs, “Note on Vaudeville Voices” in The Moderns: An Anthology of New Writing in America, edited by LeRoi Jones (New York: Citadel, 1963), 345.

19. John Willett, “UGH,” reprinted in Burroughs at the Front: Critical Reception, 1959–1989 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1991), edited by Jennie Skerl and Robin Lydenberg, 43.

20. “King of the YADS,” Time (November 30, 1962), 96–97.

21. Since its purpose was to head off censorship of Naked Lunch in Britain, Dead Fingers Talk unsurprisingly cut down explicit sexual content. Almost all The Ticket material is in the second half of the book and, unlike the Soft Machine, which is often mixed with passages from Naked Lunch, appears mainly on its own, so that seven of the last ten sections derive exclusively from The Ticket.

22. Undated half-page typescript, circa 1963 (Berg 37.2).

23. Burroughs, “The Cut-up Method of Brion Gysin,” in The Third Mind (New York: Viking, 1978), 32.

24. Rosset’s autograph comment appears on the archival original of the letter published in Rub Out the Words (Grove Press Records, Special Collections, Syracuse University; after, abbreviated to SU).

25. Burroughs to Ansen, July 2, 1962 (Ted Morgan Papers, Arizona State University; Box 1). After, abbreviated to ASU.

26. Burroughs to Gysin, August 15, 1962 (Berg 85.6). Gysin’s contribution to Burroughs’ book had a precedent: in 1960 four pages of his calligraphs had completed their coauthored cut-up pamphlet, The Exterminator. That same year Burroughs tried to incorporate drawings in Grove’s edition of Naked Lunch, having already included some with episodes published in Big Table magazine the year before.

27. The phrase “the ticket that exploded” first appeared in “Twilight’s Last Gleamings” in Evergreen Review 6.22 (January 1962), as an episode of Novia Express (sic). Grant Roman offered $150 for “your original manuscript and/or typescript, together with final version and galley sheets, of your new novel entitled Words—Falling—Photo Falling” (Roman to Burroughs, September 6, 1962; Berg 80.16).

28. Burroughs to Bowles, November 21, 1962 (HRC).

29. Burroughs to Ansen, January 23, 1963 (Ted Morgan Papers, ASU).

30. The Letters of William S. Burroughs, 1945–1959 (New York: Viking, 1993), 414.

31. Burroughs to Ansen, January 23, 1963 (Ted Morgan Papers, ASU).

32. Lotringer, 77.

33. Burroughs to Seaver, July 14, 1966 (SU).

34. Burroughs to Seaver, October 25, 1966 (SU).

35. Burroughs to Seaver, November 29, 1966 (SU).

36. Burroughs to Meeker, November 10, 1966 (SU).

37. For his ironic eulogy to the ellipsis (“the gimmick of the ‘metro-all-nerve-magic-rails-with-three-dot-ties’ is more important than the atom!”), see Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Conversations with Professor Y, translated by Stanford Luce (Champaign, Ill: Dalkey Archive, 2006) 107.

38. The phrase appears on an archival typescript following “the liquid medium of his body” in the “black fruit” section of The Ticket (Berg 10.3).

39. Olympia Press page proofs (William S. Burroughs Papers, Ohio State University SPEC.CMS.85; after, abbreviated to OSU).

40. Burroughs’ own verdict on the design was lukewarm: “Received the covers everything O.K.” (Burroughs to Seaver, April 3, 1967; SU).

41. Olympia page proofs (OSU 3.8).

42. The essay is printed in full in Word Virus: The William S. Burroughs Reader (New York: Grove, 2000), edited by James Grauerholz and Ira Silverberg.

43. Burroughs, The Yage Letters Redux (San Francisco: City Lights, 2006), 53. Burroughs repeats the phrase in Naked Lunch (91).