Читать книгу Tree - William Schey - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеGrowing Up

Despite living some distance apart, the babies were together at least once a week. Their mothers purchased buggies with space for two passengers, so they shared a “room” from their youngest days. It was doubtful that either boy actually remembered their joint excursions through the neighborhoods, but each claimed that the other took up more than his fair share of space in the buggy.

As the boys grew older, they visited even more. While their parents played cards or lounged in the back yard, they were off playing with other kids. In Tree’s neighborhood, their favorite play area was Mr. Timothy O’Brien’s lumber yard, abandoned on the weekends. The place was a kid’s delight, a couple of acres surrounded by a wire fence that made it a perfect place to play. There were mountains of wooden beams, planks, and two by fours. and the fence was easy enough to climb. So, the yard was an ideal venue for Hide and Seek, Cops and Robbers, and King of the Hill.

A junkyard dog, one fierce looking German Shepherd, turned into a pussy cat, or at least one of the guys, after they fed him chunks of hot dog, some chocolate ice cream, and beef bones stolen from the trash bins at home. O’Brien never figured out why his beloved pet rejected his Monday meal of Alpo. “Great watch dog,” he bragged, though. “Never had an intruder around here.”

Near Michael’s house on the north side, the boys played at Bicycle Hills, a well-worn path through the trees in an undeveloped part of the community. They rode their bikes to the site and raced over the three-quarter mile, hilly trail. By this age, both had heard a lot of stories about eye injuries and broken ankles, but thoughts of getting hurt never slowed them down. They suffered some minor bruises and scratches, as boys tend to do. Nonetheless, they persisted in an exuberant brand of play and made it unscathed through childhood despite their reckless abandon.

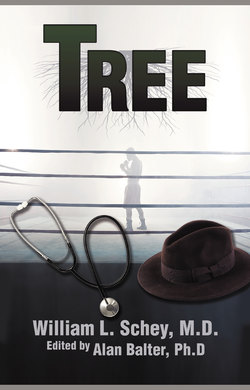

By age 12, both boys had developed special interests. Tree boxed at the local YMCA in a program designed to keep young boys off the street after school. Once he learned some of the basics, he was able to handle himself quite well, even against boys a year or two older than he was. Jack took Tree to the training facility he had attended as a youth, and the coaches provided more advanced training. He was eager to show off Tree’s ability, especially when it became clear that his son had more talent and potential than he had back when he was young.

“Hey, Jonathan, Why don’t you come on over and watch Tree spar next Saturday. I think you and Michael will be surprised at what you see.” And surprised they were. Even those with untrained eyes and no experience in the ring are quick to discern exceptional talent.

Puberty treated Michael kindly. He grew long and lean and had fine features. In opposition to the Jewish stereotype, his nose was small and straight, and he had thick black hair with bangs that hung over his forehead. He had a set of straight white teeth and an easy smile. One unusual feature was his thick eyebrows which, if left unattended, would have merged into a “unibrow” in about two weeks. So while certainly not an Adonis, Michael was good looking enough to get noticed by more than a few budding young coeds in eighth grade. He did nothing to discourage their attention.

He took to swimming with natural ease and went to the local high school a couple of times a week for instruction. The head coach was impressed with Michael’s potential and allowed him to work out with the senior high school team while he was still in junior high. This practice amounted to illegal recruitment, so Michael learned to keep his head in the water and his mouth shut.

Playing the piano was another of Michael’s interests, at least for a time. It was soon obvious, however, that interest does not always correlate with talent. He was persistent, all right, which essentially meant that he persistently played the wrong notes. When he suggested quitting, Dori said, “You’ll be happy you did this when you’re older,” the standard line for mothers whose kids are threatening to quit music lessons.

Piano teachers often feel some sense of loss when a student hangs up the old metronome. Michael’s teacher, however, after a couple of years of valiant effort and migraine headaches every Wednesday afternoon when Michael was scheduled, looked heavenward, made the sign of the cross, and wished him well. “I hear you’re an excellent swimmer.” she said. Michael, of course, was delighted at the prospect of having one additional hour a day to do anything he wanted. ‘’No more practice. Free at last,” he thought.

Tree grew to five foot six and 122 pounds by age fifteen. His boxing skill grew as well, so much so that the coach at the training facility turned him over to a former professional who taught him more advanced techniques and moves. He won a string of bouts at the YMCA, and his coach encouraged him to enter the Golden Gloves tournament. Initially, Mary was reluctant, but Tree persisted, and eventually both parents signed the permission forms.

Tree entered the Golden gloves at age 16 and won the lightweight division in the midwest sectional. His coach, a crafty old guy, had arranged for Tree to fight some former professionals even before the Golden Gloves began. Thus, Tree was essentially a professional before his career as an amateur even began. Mother was unaware of these developments, and Dad looked the other way and marveled at the symphony of motion he saw in his son. He saw a rare talent, a talent that didn’t come along very often. “He can go a long way,” he thought, “if I surround him with the right people.”