Читать книгу Richard III - William Shakespeare - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

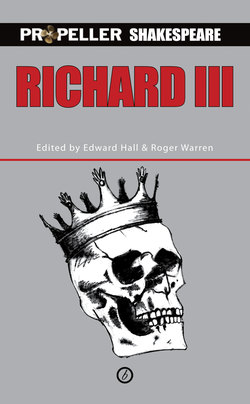

ОглавлениеShakespeare’s Richard III

Probably written in 1592, immediately after the Henry VI trilogy, Richard III is the culmination of Shakespeare’s dramatization of the Wars of the Roses, which he had begun in the three parts of Henry VI. It has, therefore, a double focus: it concludes the story of those wars, and presents a full-length portrayal of Richard himself. These two aspects are indissolubly linked. The characters constantly refer back to events of the past, especially to Queen Margaret’s ritual slaughter of Richard’s father York and his young brother Rutland, and to Richard’s (and his brothers’) murder of Margaret’s son at the battle of Tewkesbury, which saw the final defeat of Henry VI, Margaret, and the House of Lancaster. There is a strong sense of the past coming home to roost. One by one, characters reap what they have sown; and while some of them blame or curse Richard, he embodies in himself what they have been: he is the inevitable outcome of their destructive violence.

To this extent, Richard III dramatizes the ‘Tudor myth’, history as the Elizabethan chroniclers presented it, culminating in the Battle of Bosworth, where Richmond – the future King Henry VII and so the grandfather of Elizabeth I – ends a century of civil strife with the establishment of the Tudor dynasty. But, as always, Shakespeare complicates the pattern. Richard is apparently a classic image of villainy, symbolised by his deformity: a crippled mind in a disabled body. Yet he is not only the centre of dramatic vitality: he is also charming, sympathetic even, as the ‘virtuous’ characters who oppose him are not. From his celebrated opening speech, his candour about his aims lures the audience into complicity with him: we become his accomplices in his bid to seize power. Truthful to us, he exposes, with great sophistication, the vanity and hypocrisy of the political and social world.

The first half of Richard III dramatizes Richard’s rise; the second half his fall and his defeat at Bosworth. An important aspect of this defeat is that the character who tricks so many others is himself tricked – by Stanley’s treachery, but still more by Queen Elizabeth, the widow of King Edward IV. In a central scene, Richard woos Elizabeth to agree to his marriage with her daughter (sister of the princes in the Tower, whom he has just murdered), in order to secure his political safety. This scene employs the same line-by-line cut-and-thrust of Richard’s earlier wooing of Lady Anne, and Richard thinks that, as with Anne, he has won the encounter, contemptuously dismissing Elizabeth as he had earlier dismissed Anne: ‘Relenting fool, and shallow changing woman.’ But he is wrong. Elizabeth is a tougher opponent than Anne had been; we subsequently learn that she has promised her daughter not to Richard, but to his opponent Richmond. The supreme irony of the play is that the great trickster is himself the victim of a trick. Is the glorious conclusion of the play more equivocal than it seems?

Roger Warren