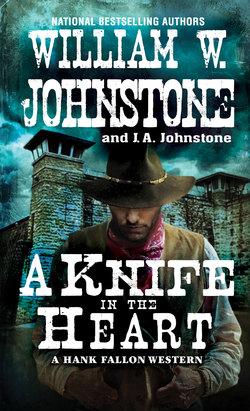

Читать книгу A Knife in the Heart - William W. Johnstone - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOURTEEN

Since Harry Fallon had worked as a deputy United States marshal, he understood how slowly the federal government liked to work. Back in 1895, the U.S. Congress approved the construction of three federal penitentiaries, one in Atlanta, Georgia; one at McNeil Island in Washington State, although that prison had been around for decades now; and here at Leavenworth. Since state prisons were beginning to fill up, Congress and the president figured that the time had come to send enemies of the country—whether they were counterfeiters or smugglers or whatever—to serve time in a U.S. prison. They had been sent to state prisons, usually, to serve their time. Those who committed federal crimes in the Indian Territory usually got sent to the Detroit House of Corrections, although Fallon had been sentenced to his hard labor at Joliet, Illinois.

Leavenworth, Kansas, of course, had long been holding prisoners. It got its start back in 1827, when Henry Leavenworth, colonel of the Third U.S. Infantry, decided a new military post needed to be established right here, on the banks of the Missouri River, more than twenty miles from the Kansas River, a prime location to protect travelers on the newly opened Santa Fe Trail. For decades, though, the fort had served as a supply depot to frontier posts from Kansas to the Rocky Mountains.

Soldiers often weren’t the most law-abiding men on the earth, and a lot of men in uniform got into trouble with higher-ranking men in uniform. Guard houses, like post hospitals, were usually full up. And for more serious offenses, a military prison was needed. So back in 1875, the United States Military Prison, also established by Congress—back in 1874—began, starting out in an old supply building that had been fitted with cell blocks and iron bars. Three hundred inmates were incarcerated there a year later.

So when the Secretary of War decided in 1894 that the Army no longer needed a prison just for offenders of military matters, Congress transferred the overseeing of the military prison at Fort Leavenworth from the War Department to the Department of Justice.

Which could have been the end of things, but, no, then the House Judiciary Committee started meeting, and the committee said that the old structure at the fort just no longer was suitable, and that’s when Congress said that a new federal penitentiary had to be built in Leavenworth. Land was allocated roughly two-and-a-half miles away.

There was a lot more going on during these meetings and votes with representative and senators and lawyers talking and dining and drinking. The Three Prisons Act did a lot to get the ball, and construction, started, but the act did not come up with any money to build those pens.

Fallon couldn’t blame the citizens for that way of thinking. Imagine if the military got tired of keeping its post in Leavenworth. Army institutions, especially on the frontier, were shut down, and now that some scholar had declared the frontier of the United States officially closed back around 1893, the good folks in Leavenworth worried that if the post—the very same institution that had made many a businessman, particularly the saloon and brothel owners, wealthy since about 1827—departed, what would become of the city on the banks of the river? Would it turn into a penal colony like Australia? Would travelers across Kansas avoid it like they would a leper colony or Alcatraz?

Anyway, in 1895, the military prison became the United States Penitentiary, and embezzlers, murderers, whiskey runners on the Indian reservations, counterfeiters, perjurers (in federal cases), and men who used the mail to send naughty drawings or photographs found a hard cot and three meals a day.

Since March 1897, prisoners from the facility at the fort had been marched those two-plus miles to help with construction. It was still going after the warden got sick of it all and tendered his resignation. That opened up the job, which the warden at the state prison in Laramie, Wyoming, had his eyes on, until Harry Fallon had to open his big mouth and start the ball rolling, and found himself taking the job.

The plan was to put twelve hundred cells in the federal pen here. Five and a half feet wide, nine feet deep, ceilings about eight feet high, with a barred door and window at the front. Since the twentieth century would be dawning shortly, each cell would have water and even some of Thomas Edison’s newfangled electric lights.

The United States government moved slowly. From Fallon’s viewpoint, so did the prisoners building their new home. He thought about the inmates who had built most of what became the Missouri state prison in Jefferson City. There weren’t nearly as many prisoners building in that hell box as there were here, but they got it done. Fallon’s pa would have called that “a problem with your generation. You young whippersnappers don’t know how to work anymore. If I was as lazy as your pals back when I was your age, my pa would’ve tanned my hide. And I’d tan yours, except you’re bigger than me.” He’d wink, but Fallon figured, deep down, his father was speaking exactly what he thought.

And Fallon, to be honest with himself, would likely agree with his pa. And the more he looked at the kids around him, in ten or twelve years, Fallon would be telling them exactly what his father had told him.

But not Rachel Renee, of course. Fallon’s daughter was perfect.

Just like her mother.

Fallon moved over to the table where men looked down at the plans designed by a couple of architects from St. Louis. That firm had gotten the lush job of designing the federal pens at both Leavenworth and Atlanta. Fallon was already sweating, and he had to remind himself that summer had not begun. He wondered if he should have asked for the job on that island in Puget Sound. On a morning like today, waves and water sounded peaceful and cool. The Missouri River was mighty fine, but also ugly, smelly, and radiating heat and humidity.

“Is this the plan?” Fallon pointed at a blueprint spread across a table, snuff cans, scrap wood, rocks from the quarry, two hammers, and one saw placed at the proper points to keep the paper from being blown halfway to San Angelo, Texas.

A man in bifocals and bowler looked up. “Yes,” he said in a nasal voice.

Fallon moved closer. He had done just a little preliminary investigating about what he was getting himself into. Now he saw the design for the prison here—if he lived to see it completed. Not that he thought he’d get killed in some riot or jailbreak. He had already helped bring back three escapees. But he might die of old age before this compound was halfway finished.

Frowning, Fallon said, “So . . . we’re looking at something under a thousand acres all total.”

The man pushed the spectacles up the brim of his nose.

“Seven hundred.”

Fallon’s head bobbed. Most of that was just land. Give the escapees plenty of land to run themselves out before they ever reached the high walls.

“This is the compound.” Fallon tapped his finger on the blue print.

“Yes, sir.”

“How many acres?”

“Sixteen. Give or take.”

He slid closer, and looked at the design. “This is similar to Auburn,” Fallon said.

The man cocked his head. “You have been to the New York state prison, sir?”

Fallon grinned. “Not that one. I put Sean MacGregor in prison before he could send me there. Or Alcatraz. Or Cañon City. Or Deer Lodge. Or . . .” He laughed in spite of himself. “But I’ve studied prisons, sir. From The Count of Monte Cristo to here.”

The Auburn prison had been built even before Leavenworth became a fort. The prisons were cavernous rectangular structures. Two barracks to serve as the wall on one side, the south side, with smaller cell blocks stretching out from the rotunda like three spokes in a wagon wheel. Corridors shaped like horseshoes to connect the rear and central buildings. The theory was that would make it harder for any inmate to escape at night. Fallon looked at the walls, nodded.

The administration building would face the south, in the middle between the two long cell houses. The three radial cell blocks jutted out, coming close to the next monstrosity of buildings. Fallon tapped one.

“What’s this?”

“Office and school,” the man in the bowler said, and went on to show Fallon the dining hall, auditorium, commissary, kitchen, even an ice plant.

Fallon smiled. “The didn’t have one of those in Joliet. Sure could have used them during the riots.”

The man made himself smile and showed Fallon the storehouses and the laundry. Fallon tapped another structure.

“That’s the dormitory,” the man said as he moved his eyeglasses down his nose.

“Dormitory?” Fallon studied the young man. Where was he? A university like Yale or someplace?

“Solitary. You know, an isolation unit.”

“Ah.” Fallon shook his head. “Yes.” He made himself nod. “Yes, Mister . . . ?”

“Baker, sir. Roy Baker. I work for Eames and Young.”

Those were the architects from St. Louis.

“Yes, Mr. Baker. Yes, I know all about solitary.” His finger slid across the blueprint.

“That’s the hospital.” The man took charge, showing Fallon the planned powerhouse, the quarantine unit, a maintenance shop, laundry, a proposed shoe factory—Fallon knew all about those, too—and something Mr. Roy Baker of Eames & Young called “Industries.” Fallon really didn’t know what Industries would be, unless another place for slave labor.

“That’s all there is, sir. That’s all a prison needs.” He grinned at his own joke.

“Very good, Mr. Baker,” Fallon said, and looked at the young man. “What do you suppose we’re missing?”