Читать книгу Asia's Legendary Hotels - William Warren - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIstayed in my first historic Asian hotel on my first visit to the region in the late 1950s. It was Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and I still remember the sense of severe disillusionment I felt when I entered the lobby late on a summer afternoon after an endless flight across the Pacific aboard one of Pan American’s China Clippers.

Exactly what I was expecting I can’t say; probably something that would immediately confirm that I was in Japan rather than Los Angeles or Honolulu. What I found instead was a low, oddly uninviting structure, built of reddish lava stone, suggesting the dark claustrophobia of a Mayan temple rather than the light, airy quality I perceived as distinctively Japanese. It certainly had an interesting history as one of the very few buildings in Tokyo to survive the catastrophic earthquake of 1923 and the fire bombing of World War II.

As I wandered through its long, dimly-lit corridors and tried to shave with the use of a mirror set about four feet from the bathroom floor, I summoned up little sense of the romance of staying in one of the world’s most legendary hotels. Perhaps other guests were similarly affected or the owners simply decided it was too “old-fashioned” for the modern image Tokyo was bent on swiftly acquiring.

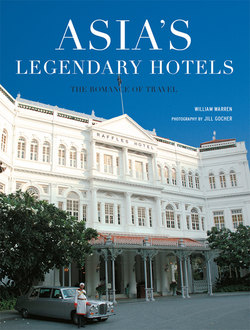

To Somerset Maugham, Singapore’s Raffles Hotel stood for “all the fables of the exotic east.” Starting as a simple bungalow on Beach Road in 1887, it grew into one of the most famous hotels in Asia, as shown in this picture taken in the 1930s when it was a gathering place for locals and international travelers.

The buildings that make up the Amangalla date back several hundred years. The hotel is situated within the walls of Galle Fort, recently declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The extensively renovated interior of the Amangalla once played host to Dutch and British soldiers.

In any event, the old Imperial disappeared a year or so later, with only a few voices raised in protest and was replaced by an ultra-modern creation where you really could be just about anywhere on Earth.

This was happening in other places too, as I discovered on subsequent travels. The great mass tourist boom was then just getting underway in Asia and as it gathered momentum whole cities were being transformed, not just their physical appearance but also in some cases their very personalities. Soon it was getting harder and harder to tell where you were from a superficial view and even more if you were staying in one of the countless hotels that had materialized along with everything else.

But my own perceptions and priorities were changing as well. Increasingly, I found myself trying to discover ways to get behind these bland contemporary façades that concealed the real cities; and as often as not the solution proved to be no more difficult than finding and booking a room in a hotel rich in local history. I was surprised at the number that were still in business, some precariously clinging to life amid all the unimaginative new construction, others lovingly restored by owners sensitive to their importance; and for me, they proved to be rare havens where the distinctive flavor of the past could be recaptured. On later visits to Tokyo, I even felt a powerful nostalgia about Wright’s Imperial and wished that some way could have been found to preserve its gloomy glory, which in retrospect, didn’t seem so anachronistic after all.

During a certain period, almost every major Asian city had at least one hotel that seemed to encapsulate its essence to visitors from afar and sometimes they had several. The names of these places spread through old travel guides, through the colorful luggage stickers that adorned steamer trunks, sometimes simply by word of mouth, from one knowledgeable traveler to another.

I am talking here, of course, about another, long-ago age of travel, when people went mostly by ship or train and took their time about it, staying for weeks or months in one place along the way. Arriving at such exotic destinations as Bombay (known today, alas, as Mumbai), Rangoon (Yangon), Singapore or Bangkok, they wanted comfort, even luxury, a home away from home. Uniformed representatives met them on arrival and conveyed them and their often copious luggage to the hotel in question, which was nearly always only a short distance away from the port or railway station.

When a ballroom was added in 1920, the Raffles Hotel became a permanent fixture on Singapore’s burgeoning social scene. Ballroom dances were regularly held until the outbreak of World War II.

Nearly all of these establishments were built toward the end of the 19th century, or in the early 20th, and most reflected pseudo-classical styles that had emerged in British India. They had vast lobbies (in which the newcomer was more than likely to run into a wandering friend or two), restaurants that served familiar food along with a few more exotic native dishes, enormous rooms usually divided into several separate areas for living and sleeping, long corridors and impressively large staffs (in 1912, the Raffles Hotel was said to have 250 staff) ready to attend to one’s every need. If the climate was tropical, as it often was, there were broad verandahs on which to relax in the early morning or late afternoon, ample ventilation to catch any passing breeze, mosquito netting over the beds and sometimes bathing facilities that consisted of huge jars from which one splashed cool water with the aid of a dipper (always worth an amusing mention in letters back home). In more temperate places, like the hill stations that were such a popular feature of colonial life, there were lap rugs, blankets, hot-water bottles and fireplaces regularly kept stoked on chilly evenings.

Later, in a number of prosperous ports of call such as Hong Kong, some hotels rose to such dizzying heights as eight or nine stories and offered such innovations as lifts; but the majority of them were relatively low buildings that sprawled over extensive landscaped gardens, with plenty of room for a stroll away from the teeming city streets outside.

An Englishwoman named Alice Beaumont was somewhat unusual in that she set out alone on a grand tour of Southeast Asia in 1902, but her reactions to where she stayed were typical of other travelers. Disembarking at the wharf in Rangoon, she duly noted in her diary:“I climb into the cab of an elderly Hindoo [sic] gentleman who spirits me away from the dock… Our destination is the new Strand Hotel, opened only last year by the estimable Sarkies Brothers… From the chalk white façade to the ‘chess-board’ tiles that embellish the lobby, everything about the Strand evokes the sort of luxury that has been sorely missed on my long journey from England.” The Raffles Hotel offered a similar refuge in Singapore (“I occupy the mornings touring this ever-alluring metropolis, the afternoons writing in the shade of the Palm Court before retiring to the Tiffin Room around tea time to plot my next step in this long trek”), as did the Oriental in Bangkok (“My room is supremely comfortable, with huge shutters opening out on to a tropical garden”) and the Metropole in Hanoi (“suitably grand for a city newly honored as Indochina’s capital”).

The Raffles Hotel began life as a simple 10-room bungalow before two new wings were constructed in 1890, marking it out as one of the leading hotels in the region.

The Ananda Spa is spread over 21,000 square feet (1,950 square meters) and offers dozens of treatments incorporating Ayurvedic and Western techniques. The heated outdoor lap pool offers breathtaking views of the Himalayas.

It might be noted that Miss Beaumont actually met her future husband during one of those plotting sessions at Raffles’ Tiffin Room and became engaged to him while exploring Angkor in Cambodia three months later. Excerpts from her diaries were published in 2000, together with an account of a parallel journey made by her great nephew, who stayed in many of the same hotels.

The Taj Lake Palace in Udaipur was conceived as a private retreat and is accessible only by boat. It is perhaps best remembered as one of the magnificent locations used in the James Bond film Octopussy.

Despite their physical similarities, each great hotel had a distinctive ambiance all its own or acquired one over the years. Taking tea in the grand, gilded lobby of Hong Kong’s Peninsula, for example, you had a panoramic view of Chinese junks plying the busy harbor and white buildings climbing dramatically up the Peak on the other side. The Raffles had the private Palm Court that so appealed to Miss Beaumont on hot afternoons, a billiard table under which a tiger was supposedly discovered and a Long Bar where the potent Singapore Sling was first concocted. The splendid Taj Mahal in Bombay overlooked the Gateway of India, the first thing countless arriving Englishmen and their memsahibs saw of the subcontinent and offered special rooms for the personal servants who often accompanied guests. From the art deco lobby of the Cathay, where sleek Chinese ladies showed off their shimmering silk gowns, one could ascend by lift to a roof garden overlooking the Bund, that highly visible concentration of Shanghai’s power and wealth.

All kinds of travelers turned up in such settings—royalty, both genuine and bogus; dignitaries representing some government or other and suave conmen looking for a score; globe-trotting stars or stage and screen and world-weary socialites; writers in search of fresh material to fire their imagination and usually finding it; even a few of what would soon be known as ordinary tourists, though well-heeled ones on the whole.

Some left lasting impressions: Somerset Maugham, for instance, seems to have stayed at just about every historic hotel in Asia and a remarkable number have commemorated that fact by naming a suite after him. Noel Coward was almost as ubiquitous, adding to his (and the hotel’s) renown by writing Private Lives in just four days while confined by the flu to a suite at the Cathay. For five years, until the Japanese rudely interrupted his comfortable life, General Douglas MacArthur made his home in a penthouse atop the Manila Hotel, where it is still proudly preserved.

The four Sarkies brothers, Armenians who founded several of Asia’s most famous hotels in the late 19th century, among them the Eastern & Oriental in Penang, Raffles in Singapore, and the Strand in Yangon (Rangoon).

World War II marked the end of this era of leisurely travel, abetted by a dozen other more local conflicts that followed in its wake. One by one, willingly or otherwise, the colonials departed, carrying their memories and souvenirs off to homelands some of them only dimly remembered; new rulers took their place, with a different set of aspirations; new city centers rose, often out of near-total ruins and often, too, far from the old ones; air travel became the preferred mode of transport, though curiously, despite the greater speed that resulted, there appeared to be less time to experience places than there had been before.

The old hotels faced a growing dilemma. They had been built for a breed of traveler who seemed suddenly to have vanished, not for group tours who barely slept in their rooms or businessmen who wanted instant communication with foreign countries and all sorts of other novelties. Economic considerations were even more serious. Many of the rambling structures were in deplorable condition, suffering either from effects of war or too many years of neglect and frequently changing management. Roofs leaked, floorboards creaked, rising damp discolored the walls. Money was needed to bring them back to their former splendor, and a lot of it. Still more was needed for the large staffs still required to tend those generously proportioned suites and public rooms, not to mention for the modern bathroom fixtures and air-conditioning systems everybody now demanded. How else were they to compete with the glass-walled new hotels that were going up, no matter how deficient these rivals might be in atmosphere, service, and above all, history?

The lobby of Raffles hotel, each floor containing lounges for guests. The venerable hotel was extensively renovated at the end of the 1980s and is now preserved as a national heritage structure.

Painting of the original Oriental Hotel when it opened on Bangkok’s Chao Phraya River in 1884. Designed by a local firm of Italian architects, it was the Thai capital’s first grand hotel and, for many years, the only one.

For some, the challenges were simply too overwhelming and they gave up the fight, either closing altogether or replacing the old building with a new one on the same site, as happened with Tokyo’s Imperial. Several continued to exist physically, but in such a state of disrepair and squalor that not even the most determined seeker of nostalgia would want to spend much time in them.

Others though, resisted extinction and gradually (very gradually in a few cases) realized that being historic might not necessarily be such a bad thing after all. Not all the new breed of travelers, it turned out, were so enchanted with contemporary accommodations. Indeed, quite a few of them were looking for just the sort of atmosphere the old hotels offered in abundance, even if it happened to be in a now unfashionable or inconvenient part of the city. Sometimes it turned out that a beguiling sense of history could be provided in buildings that were not hotels at all originally but still had architectural distinction. Thus Singapore’s old post office became the elegant Fullerton, the former High Commissioner’s stately residence in Kuala Lumpur became an all-suites retreat called the Carcosa and more than a few fairy-tale Indian palaces underwent extensive renovations and opened their doors to paying guests. Another successful strategy, pursued by many, was to add an ultra-modern wing while preserving all or most of the older sections and thus satisfying several tastes.

This wave of restorations and conversions began in the early 1980s, gained momentum in the 1990s and today extends through much of Asia, from India to China. The result, as seen on the following pages, is a collection of unique establishments where the past is not only present, but celebrated—and where one can discover what it was like to travel when a hotel was more than merely a collection of rooms and a restaurant or two.

The Shiv Niwas Palace was formerly a royal guest house. Situated on a hill overlooking Udaipur, the Shiv Niwas offers spectaculat views of Lake Pichola.