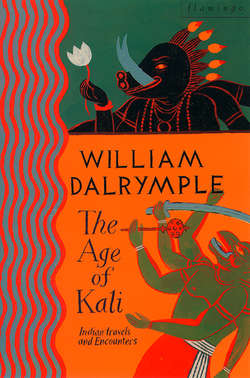

Читать книгу The Age of Kali: Travels and Encounters in India - William Dalrymple - Страница 13

East of Eton

ОглавлениеLUCKNOW, 1997

Just before dawn on 7 March 1997, two figures made their way to a small classical bungalow on the perimeter of La Martiniere College in Lucknow, India’s oldest and once its most distinguished public school.

Walking silently to the back of the building, they found a broken windowpane looking in to the bedroom of the school’s Anglo-Indian PT instructor, Frederick Gomes. The two took aim and, at a signal, fired at the sleeping figure with a .763 Mauser and .380 pistol. One shot missed, but the other hit Gomes in the leg. The schoolmaster immediately leaped out of bed and hobbled in to the corridor.

According to the police reconstruction, the two killers then ran round to the front of the building, kicked open the front door and took some more shots at the terrified man, wounding him in the back as he tried to run back to his bedroom. Bleeding heavily, Gomes succeeded in shutting the door and barricading it with a chair. But the killers returned to the back and fired a random hail of bullets in to the room through the window. When Gomes’ body was later discovered by another schoolmaster, the PT instructor was found to have sustained no fewer than eight hits: four in the chest, one in the leg, two in his back and the fatal one on his temple.

The murder, which remains unsolved, created a sensation in India, particularly when several guns (though not the murder weapons) were found to be circulating among the school’s pupils. For La Martiniere is an institution of legendary propriety and distinction, as pukka as Kipling himself, who appropriately sent his fictional hero Kim to a Lucknow school – St Xavier’s – clearly modelled on La Martiniere. During the Raj, the school produced generations of District Magistrates, Imperial civil servants and Indian Army officers, and the names of many of these Victorian pupils – Carlisle, Lyons, Binns, Charleston, Raymond – are still carved on the front steps of the school. Since then La Martiniere has educated several members of the Nehru–Gandhi dynasty, as well as producing great numbers of cabinet ministers, industrialists and newspaper editors. If India’s increasingly endemic violence and corruption could creep in to such an institution, it was asked, what was the hope for the rest of India? ‘The killing is a metaphor of our times,’ I was told by Saeed Naqvi, one of the country’s most highly regarded political commentators and an old boy of the school. ‘For such a level of violence to reach the groves of academe and the sacred precincts of La Martiniere is symbolic of the way the country of Mahatma Gandhi has completely ceased to be what it once was.’

In Britain there may have been widespread celebrations marking fifty years of Indian Independence, but in India there has been much less rejoicing. As The Times of India acknowledged in an editorial to mark the 1997 Republic Day, ‘in this landmark year not much remains of the hope, idealism and expectations that our founding fathers poured in to the creation of the Republic. In their place we now have a sense of abject resignation, an increasing sense of drift. We are ostensibly on the verge of a global breakthrough; yet the truth is that the deprived India is eating voraciously in to the margins of the prosperous India.’

If decay and corruption have set in to many of the old institutions of the Raj, the public schools that the English left dotted around the subcontinent have always vigorously resisted any accommodation with the post-colonial world outside their walls: however much India and Britain may both have moved on since 1947, India’s public schools have, for better or worse, maintained intact the ways and attitudes of early-twentieth-century England. ‘Independence changed nothing at La Martiniere,’ I was told by one old boy. ‘The curriculum didn’t change, the boys didn’t change, the games didn’t change, the discipline didn’t change. They kept the Union Jack flying from the roof well in to the mid-sixties. [The Hindu festival of] Diwali continued to be celebrated as Guy Fawkes Day. Even today they teach the history of the First War of Independence [the Indian Mutiny] from the British point of view.’

‘The literature, poetry and music are still English,’ I was told by another old La Martinian. ‘The manners, tastes and customs are English, even the sports are English. In my day there was very little about the history or culture of Continental Europe, and nothing at all about the history and culture of India. In fact we were encouraged to forget all the Urdu culture we had learned at home. Instead, we were always taught about all the brilliant things that British civilisation was about, and how we paan-chewing Indians were basically degenerate and we’d never get anywhere. Look how far the British had come, they told us; the sun never sets on the British Empire. We were indoctrinated in to believing that talking in Hindi, reciting Urdu poetry, wearing khadi, chewing paan and spitting in to spittoons – all this was vulgar and obscene, and after a while it really did seem like that to us. Still does sometimes.’

La Martiniere was founded in 1845 by Major General Claude Martin, an enigmatic Frenchman in the service of both the East India Company and the Nawabs of Lucknow, the last Muslim dynasty to rule India. In life Martin lived like a Moghul; in death he adopted the Moghul practice of building a tomb to commemorate his achievements. But in his will he broke with tradition by leaving the somewhat bizarre instruction that a school for children of all religions should be established in his vast mausoleum.

So it was that within this strange Indo-baroque necropolis complex, India’s first English public school opened in 1845. Here, everything that might be expected in a school on the banks of the Thames was exactly reproduced on the banks of the Gomti, right down to the statutory inedible food and the oddball cast of eccentric schoolmasters. Of these, according to Saeed Naqvi, none was more memorable than Mr Harrison.

‘Harrison had a huge moustache which he used to wax,’ remembers Saeed, ‘and he also had a talking parrot which used to say things like, “Rise and shine, rise and shine” – you know, the usual public school nonsense. Chaufin, a friend of mine in school who hated Waxy for a variety of very valid reasons, used to get up in the morning at five o’clock and tried teaching the parrot to say, “Waxy is a bastard, Waxy is a bastard.”

‘He did this with such an absolute sense of dedication and purpose that in a year’s time the parrot picked up the line, and every time Waxy walked past he’d squawk, “Waxy is a bastard, Waxy is a bastard.”

‘Now, Waxy thought this was a joke, but then one day he was taking Doutre, the headmaster, on a tour of all the wonderful things he was doing to the dormitories, and as he walked past the parrot recited the famous line. So the story had a very macabre ending, because Waxy in his temper twisted the neck of the parrot; and that was the end of Waxy’s parrot.’

On the surface, little appears to have changed at La Martiniere since Saeed left thirty years ago. Now, as then, boys of all religions still attend chapel every day, listening to a choir made up of Muslims and Hindus dressed in white surplices sing the ‘Te Deum’, ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘The Lord is my Shepherd’. The masters still wear black academic gowns, the curriculum and uniform remain firmly those of the English public school of the 1930s, and khaki drill, cricket, the works of John Buchan and furtive schoolboy homosexuality are apparently all still very much de rigueur. Urdu or Hindi literature is never taught; instead pupils still learn by heart great swathes of Wordsworth, Tennyson and Byron.

One morning, after the boarders had attended chapel and the whole school had massed at assembly to sing the school hymn, ‘Bright Renown’, I talked to some of the boys who were doing their prep in the spectacular Moghul-Gothic school library. At the rear of the room, the form mistress, Mrs Faridi (who earlier in the morning had doubled up as organist on the old manually-pumped organ in the chapel), was looking around her, scowling through her hornrims and shouting out: ‘Settle down now, boys! Settle down!’