Читать книгу Letters of William Gaddis - William Gaddis - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2. The Recognitions, 1947–1955

To Edith Gaddis

[In the spring of 1947, WG left New York for several years of traveling as he worked on The Recognitions, which began as an early effort entitled Blague. He began by heading south for Mexico in a Cord convertible with a friend named Bill Davison.]

New Orleans, Louisiana

[6 March 1947]

dear Mother—

after much fortune and misfortune we are off to Mexico, I hope this afternoon. I trust that you got my wire, so that when we reach Laredo I shall have birth certificate and be able to get visa. It must be a student’s visa, however, which disclaims any attentions on my part to get a job while there, since they have a sort of protective immigration. The point being that it will take a little while after I get to Mexico City to arrange through any contacts I may have to get a job, a little to one side of authority, as it were. I hope that you will be able to send me some money there—can you conveniently? We are leaving here with next to nothing, as you may imagine, and are taking on a passenger, the fellow who has been our host, and who I gather will be able to finance a good part of the trip from here on. You may gather from my letters the state that things have been in. But I just feel that once we get to Mexico city, and if you can send me some money there, that things will start to shape up well. The address is c/o Wells Fargo Express Company, Mexico D. F., Mexico, and to be marked Please Hold.

Also to add a touch of trouble, my leather suitcase stolen from the car last night, therewith all of my shirts, neckties, and all of the work I was taking with me. As for the work, it is too bad, but perhaps for the best since I plan to start rather freshly with writing when I get down there, and now will not have these things which I have written over the last year or two to distract me. The business of the shirts and ties, of course—infuriating. and the bag.

I want of course to write you a real letter, describing the pleasant parts of the trip, and what this city is like—certainly how much you would like it. But one minute we are to stay; the next, to leave; the next, to leave with a passenger. And now suddenly when it looks like we may get off in about an hour things are rather flurried. Health, and such things that may be worrying you, are all all right.

My love,

W

To Edith Gaddis

Rhodes Apartment Hotel

611 La Branch St.

Houston, Texas

9 March 1947

dear Mother—

Here we are, our plans made for us this time by a pretty ghastly breakdown of the car. and so I can take the opportunity to write you rather more of a letter than I have been able to manage in some time. And perhaps modify a few things which have perhaps troubled you; coming as they have in peacemeal sentences as bulletins on a consistent state of calamity.

Still I know what you are feeling under it all: even if there are occasional concerns (I imagine that the story of the suitcase gave you rather a turn) it is much better because things are happening, and moving, and alive, and not in one corner of Greenwich Vill. —and as long as I am eating and sleeping & everything is all right. Good. I feel just that way.

Washington, as you could gather, was a pretty messy business, chiefly because of the cold. So windy and cold, and the blizzard, and sleeping on Mike’s floor, chiefly difficult because we were both so discouraged at being stuck so near to NewYork, as if we might never get further. And so when we could leave we streaked out for South Carolina, and stopped at Chapel Hill. There a man of about 40 named Noel Houston teaches, and I have read a few of his pieces in the New Yorker, quite good. Well over a year ago a girl named Alice Adams who was at Radcliffe whom I knew quite well, mostly through Jean and later (and in New York) through Mike &c had told me that she wanted me to meet him. At any rate, we got there in the middle of the afternoon, drove out to his house and introduced ourselves, and spent until almost 7pm having a couple of drinks, and he talking at length about the NYer and its stories, the business of writing, &c&c, all in all very pleasant. We had, having heard of how affable he was, hoped that he might put us up somewhere for the night, but on arrival discovered that his wife and two children were ill, and so could hardly presume. Decided that the only thing to do was drive straight through to Atlanta and warm weather, Chapel Hill being similarly cold to everyplace we had left. Well, the drive that night was about the coldest thing I have ever managed. Oil being eaten up by the car, so that we must stop and try to pound holes in oil cans with nails and a rock, dark, and our hands and fingers like sticks. The only thing that saved it was good humour and a little profanity, for Davison is good in both. Finally, after one of those nights we always remember because they defy ever coming to an end, we got to Atlanta for breakfast, about eight. And never again mention Peachtree Street to me. It may have been magnificent after the War Between the States, but now the most tumblesome hurly-burly of trollycars, pedestrians, idiot drivers, and unattractive storefronts I have ever seen. We escaped about an hour later. The most infuriating thing, of course, was the weather—Georgia was quite as cold as Washington had been. And then at a town called Newnan, the radiator, which had to be flushed out, boiled, dipped, and all manner of endless treatments. The only thing was 2$ worth of room for the night. Which we needed. And so found it, and there a bath, shave, and suddenly nothing to do at 6pm. Odd dismal supper, and now 6.45—what but the movies? Two or three glasses of beer might have passed a pleasant hour, but no beer in Newnan. And so we sat through (and I am afraid almost enjoyed) a monstrosity called The Strange Woman, as Hedy Lamarr preached against such sins as Newnan probably never dreamt. Out on the street (in the courthouse square, needless to say), the clock struck—one could know the number of tolls before they were over—it was 9pm. Not a soul stirring, and a beautiful night. Stars, and not a sound. And so, after a brief walk, back to our home, where we collapsed.

The next day was another dedicated to the search for warmth, consisting of thundering out of Newnan and arriving in Mobile late in the evening. There we drank much coffee, ate many doughnuts, and finally drove down a long sideroad to sleep, for the first time on this ‘camping trip’, out-of-doors in our sleeping bags. Of course you know what happened. About 1am we were aroused by the gentle southern rain, teeming down upon our bland upturned faces. After what passed for sleep in the car, the road which he had driven down in the dark hours earlier proved one magnificent bank of mud, and I still marvel that we managed to reach the highway; obviously there was reason, for any fate which was attending us had more gruesome circumstances than a mere Alabama mudhole to address us to.

For just about cocktail time (I use it only as a figure of speech, to indicate the hour, for no one thought of such an amenity) we arrived in New Orleans. There the fun started. And it was so consistently folly that I cannot take it from day to day. Enough to say that we slept in the car for a few nights (I have not thought it necessary to mention that it was raining—rain such as Malay gets once in a generation), being low enough on funds to consider selling the car and sailing across the Gulf (until we were told that sailboats bring around 1500$), and other similarly unfelicitous notions. We spent one night in a great house belonging to friends of Bill’s family, who apparently had not been posted on his standing (though one look at either of us should have told them that we were not exactly eligible bachelors). The living room was so big that a grand piano was passed quite unnoticed in one corner; there were, as a matter of fact, two kitchens, abreast of one another for no reason that my modest eating interests could resolve, and a dining room which should have been roped off and ogled at. By this time we had become rather legendary mendicants, with a good part of the city crossing the street when we approached. Fortunately New Orleans has a French Quarter. I was pulling at what was becoming a rather eager mustache and waiting for the time-honoured greeting: “Hello, friend/ Where are you from?”, this being the first step to any southern or western jail on a vagrancy charge, when we were introduced to a young man by a girl who had not the sense to see the desperation in our characters, and pictured us fondly as Bohem . . . This southern gentleman (for he is, or rather was before he became involved with us) found something in us which prompted him to offer an apartment which was kicking around in his hands. And therewith another resolve: sell the automobile, live for a little time in New Orleans, perhaps even work, and then go to Mexico in somewhat less sportive fashion than a Cord car. Oh, the gladsome effect of plans and resolution. We moved out of the car, into the apartment, had the lights and gas turned on, bargained with a passerby to sell the Cord for 300$, I wrote you a letter giving my address and settled state of mind, clothes were taken to be laundered and cleaned, and we drank a quiet glass of absinthe in what was once Jean Lafitte’s blacksmithshop and went ‘home’. As was well to be expected, dawn broke the following morning and so did everything else. The real-estate company appeared with legal forms which practically made us candidates for the penitentiary for our brief tenancy. The man who had made arrangements to buy the car had talked with some evil companion who convinced him that nothing could ruin him so quickly as a Cord (which is something I cannot quite deny flatly at the moment), and once more we were free to blow our brains out in the streets. But even New Orleans has laws against that, so what could we do but take miserable pennies to Lafitte’s and invest them, this time in defeatingly tiny glasses of beer?

The proprietor of Lafitte’s is a man whose name has passed me without ever leaving a mark. He is quiet, pleasant, 42, and believes that everyone should have a quiet little pub of his own, at least fifty yards from his. I approached him modestly simply to ask if he had any sporting friends who thought life had come to such a pass that they would enjoy sporting about the Quarter in a long low and very moderately priced automobile. From there we went on to the intellectual world, bogged through its vagaries for a little while, and after I had proved my metal by reciting a few lines from T S Eliot, he encouraged us with tasteful portions of absinthe and loaned me 10$.

Mr Hays, introduced earlier in the letter simply as a ‘southern gentleman’, being about our age, took it upon himself at this point to be our host, until some stroke of God, like an earthquake or tidal wave, could waft us out of his city (have I mentioned that it was still raining?). His mother, a true southern lady who proved herself so b[y] retaining her sanity throughout the whole thing, was at first reasonably horrified to see us appear with our natty sleeping bags and recline in what were to us perfectly familiar contortions on her living room floor. Two days later, when she was beginning to manage to breathe again, I picked up a cold which dissolved the forepart of my face to such an extent that even an ourangatang (spelling, you see, is again a distant world)’s mother instinct would have leapt with succour. From then until we disappeared, carrying her son with us, she was splendid.

Her son, familiarly known as Sam, paints. In fact, he is doing that just at the moment. He is facing one of the most terrible architectural monstrosities that the Catholic Church ever erected, for some cabalistic reason, behind our hotel. Houston, in what I trust was a surge of civic pity, displays the thing on coloured picture postals, and I shall send you one so that you, too, may marvel.

As I have intimated, Sam, being at what we like to call ‘loose ends’, decided to throw in his lot with us, and, he having a small but at this time of the world provident allowance, we decided that it would be all for the best. And so the next morning (I say loosely, having no idea just what it was next after) we went down to the car. Since one of my suitcases had been stolen, there was more room for his luggage, and at this point it matters very little whether I appear shirtless and tieless in any of the capitols of the world. We fled. Have I said that it was still raining? If so, it was stark understatement. Driving through the bayous of Louisiana was like an experimental dive with William Beebe, and, except for the shimmering streams that poured through the crevices around the ‘convertible’ top, into our huddled laps, the Cord might have been a Bathysphere. Lonely cows on the highway appeared as splendid Baracuda, and the dismally soaked Spanish moss luxuriant submarine vetch. Across one Huey Long bridge after another, until we stopped in a town called Houma, having taken a wrong turn so that we were headed blithely for the Gulf of Mexico. We ate, considered, reconsidered, and started again west, stopping at a gas station for water (as, I have neglected to say, we have been doing every score of miles since we left). There was a small dog, the black spots of his coat blending gently into the white with the aid of the automobile grease in which he slept, and eyebrows which curled distantly away from his unreasonable cheerful face. He joined the caravan, which set forth again into a downpour which would have made Sadie Thomson play the Wabash Blues until Pago Pago slid into the sea.

There is a town in Texas called Orange, for reasons which only a native could know. Here came the scene of the final depredation. The Cord began to make the most terrifying, and, to one so much attached, sickening noises, that the only thing to do was motor down a sideroad, pretend that there simply was no top on the car, and be lulled into a delicious and thoroughly sodden unconsciousness. When we awoke, the one watch in the company indicated that the morning was well along. The amount of water that was cascading down between us and any hope of heaven made the time a compleatly negligible factor. There was nothing to do but drive down the road and get stuck in someone’s driveway. That is what we did. It was cold, and the rain so near to being one mass of moving water that we stood like three creatures in different worlds, shouting to each other as one might from inside an incandescent lamp.

We eventually recovered the car, now powered only in first and fourth gears, and limped into Houston. We had such a stroke of luck here as to convince me that we are being fitted out for the most violent end—something like driving unexpectedly into a live volcano-mouth in that country to the south, for here in Houston we have found one of the only Cord mechanics in the southwest. The Cord is now hanging in his establishment, where the most amazing array of toothless gears are exhibited on the floor. The whole thing is under the constant surveillence of Houma, the folly-ridden animal who remains, in spite of his new lot, our friend, looking up from his bed of transmission grease with the ingenuous faith which I have been mistakenly looking for in human beings.

Our apartment in Houston has a living room, bedroom, bath, kitchen, and breakfast nook. Last night we prepared a magnificent dinner (hamburger-with-onion, pan-fried-potatoes-with-onion, spinach-with-onions), and are now looking forward to this evening’s culinary adventure. During the day we saunter through the streets and stare at the citizens, or stand in our parlour and stare at the atrocity which I mentioned earlier. We smoke a brand of aptly-named little cigars Between-The-Acts, and blow ponderous rings. We discuss only earth-shaking topics, such as whether or not there really is a sun, or were we brought up with a heat- and light-emanating mirage. We smile stupidly at one another, drink coffee, and nod our heads in answer to nothing at all.

While the world of fact drowns us, that of probability supplies an occasional bubble of life, and we plan (I use the world plan as an indication of my vocabulary weakness) to arrive gloriously in Laredo sometime toward the end of the week, Friday sounding as likely as any day I can call to mind at the moment. In these ensuing days I hope to work (there is another word) on something which has been on my mind (and another) for a couple of weeks, and since all of the deathless prose which I had expected to work on was purloined with the gay vestments of my formal existence, perhaps I shall be able to make a fresh start in the world of art.

Living in a world of my own, I have no notion of the US mails. This is undoubtedly Sunday, because the steepled monstrosity across the street has been breathing a regular stream of Texan Catholics in and out of its gabled nostrils all day—and you may get this message near the middle of the week. And so I cannot say whether you will find me at the Rhodes Apartment Hotel by mail, for the moment that the auto is able to stand by itself it is in for a fast drumming south. I trust that you got my frantic wire, asking for a means of proving my identity (the only other thing I had was a Harvard Bursar’s card, in the stolen suitcase, which I suppose might not have got me a visa), and even that the birth certificate is now filed under general delivery at Laredo. The picture of $ still confounds me—it continues to leak in somewhere, and until it stops no appeals will be made. I do think, as I mentioned in another letter, that once in Mexico DF, with no job immediate, that I shall have to hold out an open and empty palm. Until then, here are the probable addresses—Wells Fargo, Monteray (you might check on what county of Mexico that’s in, and also make certain that they have an agency there), and then, in perhaps a couple of weeks, W—F—, Mexico D.F., Mexico.

I hope, trust that everything is well, you, and the things around you. I shall think of NewYork tonight as I wash my socks and underpants, articles which have seen considerable service.

My love,

Bill

Mike: Mike Gladstone (see headnote to 26 June 1952), who was staying at his sister’s apartment then.

Noel Houston: an Oklahoma native (d. 1957), author of the novel The Great Promise (1946).

Alice Adams: prominent fiction writer (1926–99), raised in Chapel Hill.

The Strange Woman: 1946 film directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, about a scheming woman’s affairs with three men.

Jean Lafitte: a pirate who worked out of New Orleans in the early nineteenth century.

William Beebe: American naturalist and deep-sea explorer (1877–1962).

Sadie Thomson [...] Pago Pago: a prostitute in W. Somerset Maugham’s early story “Miss Thompson” (later retitled “Rain”), best known in its movie adaptations (Sadie Thompson, 1928; Rain, 1932). Sadie works the South Pacific island of Pago Pago, and “Wabash Blues” is a popular song from the early 1920s that she plays on her phonograph.

To Edith Gaddis

Houston, Texas

[16 March 1947]

Dear Mother—

You, I know, have spent much time in lesser cities of the United States—but never let fate hold anything for you like Houston, Texas. It is really pretty ridiculous, pretty dull, pretty bad. But we are leaving tomorrow—Monday—having had quite a “rest”. I have written one story here, whose merits I find less each time I think of it, and at the moment have no idea of what to do with it. That, however, is hardly a major worry just now.

To explain the wire—and many thanks for sending the 35—they require much identification here to cash a money order, and, since my wallet was in the stolen suitcase, I have absolutely none—living in constant fear of being picked up for vagrancy before we reach Laredo, since I do not look like a leading citizen in my present attire.

Heaven knows, now, whether we shall make it or not—but we are again starting off. I only hope that the border will not present too many foolish difficulties, since one look will convince any official that we are not young American tourists with untold financial resources—but once across the border I shall feel much better about all sorts of things, including the hopeful sproutings of a mustache, which at the moment is as unedifying as it is rigorous in its growth.

Love—Bill

wire: on 15 March WG wired a Western Union cable that reads: “VAGUE INSANITY PREVAILS. 35 DOLLARS WOULD SUSTAIN THIS HOUSTON IDYLL. SEN[D] TO ROBERT DAVISON CARE OF WESTERN UNION HOUSTON EXPLANATION FOLLOWS MY BEST INTENTIONED LOVE= BILL”

To Edith Gaddis

Hotel Casa Blanca

Mexico City

[7 April 1947]

Dear Mother—

Well—Finally Wells-Fargo opened—Mexico, you see, has been enjoying a four-day holiday for Santo Semana—Thursday through Sunday, everything closed. And so we have been living on about 2 pesos a day—borrowed, and now repaid as is our hotel bill.

Will I continue to disappoint you, cause you wonder? Because no big long talks with an American magazine editor here who gives the same story as all—no money to Americans in Mexico, unless they are “in on something.” The Mexico City Herald finally told me to come back in 2 or 3 weeks—and I finally understood that the best I could do there was about 10 pesos a day, for 8 hrs. proofreading.

But do not be disappointed immediately—for here is something heartening I hope. I have been working very hard. Many days. On a novel. It is something I have had in mind for about a year—had done some on it in fact, and the notes were stolen in New Orleans. But now I am on it, and like it, and believe it may have a chance. Right now the title is Blague, French for “kidding” as it were. But it is really no kidding. Silly for me to write about it here, though it is practically the only thing I think about. Now: Davison’s father is attorney for Little Brown & Co., the Boston publishers. And so I can be assured that if I can do it to my satisfaction, it will be read and if anyone will publish it, it will stand best chance there, since he has some “influence.” The really momentary problem is whether to do the first part, and an outline (which I have done) and try to get an advance—or to finish it now if I can.

What we hope to do—is sell the car, buy some minor equippage, including two horses, and set out and live in the less populous area of Mexico. And there I hope to finish this thing, while Davison lives outdoor life which he seems to desire, and I am not averse to as you know.

Could you then do this?: Send, as soon as it is conveniently possible, to me at Wells-Fargo:

My high-heeled black boots.

My spurs.

a pair of “levis”—those blue denim pants, if you can find a whole pair

the good machete, with bone handle and wide blade—and scabbard—if

this doesn’t distend package too much.

Bible, and paper-bound Great Pyramid book from H—Street.

those two rather worn gabardine shirts, maroon and green.

Incidentally I hope you got my watch pawn ticket, so that won’t be lost.

PS My mustache is so white and successful I am starting a beard.

Santo Semana: i.e., Semana Santa (Holy Week), which culminated on Sunday, 6 April 1947.

Davison’s father: at the top of the page, WG adds this note: “He is R. H. Davison—15 State Street—Boston, if you want to communicate with him for any reason.”

Blague: in a later letter (7 April 1948) WG describes this as “an allegory, and Good and Evil were two apparently always drunk fellows who gave driving lessons in a dual-control car,” but this is only a frame-tale enclosing stories of the lives of New Yorkers similar to the Greenwich Village sections of R.

Great Pyramid book: Worth Smith’s Miracle of the Ages: The Great Pyramid (Holyoke, MA: Elizabeth Towne, 1934), a cranky book that translates apocalyptic messages from the Great Pyramid of Geza (predicting Armageddon in 1953), which WG surprisingly took seriously and cites a few times in R.

H — Street: WG lived at 79 Horatio Street in Greenwich Village while working at the New Yorker.

To Barney Emmart

[A lifelong Harvard friend who worked in marketing in the 1950s, taught English for a year at the University of Massachusetts (1967), and died 1989.]

Mexico City

April, 1947

dear Barney,

Just a note of greeting. And to say that I earnestly wish you were here, because I am working like every other half-baked Harvard boy who never learned a trade—on a novel. Dear heaven, I need your inventive store of knowledge. Because of course it is rather a moral book, and concerns itself with good and evil, or rather, as Mr. Forster taught us, good-and-evil. You see, I call out your name, because other bits of life proving too burdensome, I have taken to the philosophers—having been pleasantly involved with Epictetus for about a year, and now taking him more slowly and seriously. And of course I come upon Pyrrho, and see much that you hold dear, and why. Also David Hume, whose style I find quite delightful.

Shall I describe Mexico City to you? It is very pleasant, and warm, and colourful of course—and we are here, and cannot get jobs because we are tourists, and live on about 30¢ worth of native food a day. And I’m sure you would like it. Also, we grow hair on our faces. And plan, as soon as we can manage to sell the Cord—beautiful auto—to purchase two horses, and the requisite impedimenta, and go off and live in the woods, or desert, or whatever they have down here. There I shall finish Blague—that is the novel. And have George Grosz illustrate it—he has the same preoccupation with nates that I do—grounds enough to ask him.

Well old man, this is just to let you know dum spiro spero—I haven’t learned Spanish yet—a noodle language if I ever heard one. Please give John Snow my very best greeting, tell him I shall write, would give anything for a drink and talk with you all. But must work. A dumb letter, but I am very tired.

Anyhow, my best—

Bill

Forster [...] good-and-evil: in The Longest Journey (1907), E. M. Forster writes, “For Rickie suffered from the Primal Curse, which is not—as the Authorized Version suggests—the knowledge of good and evil, but the knowledge of good-and-evil” (part 2, chap. 18).

Epictetus: Greek Stoic philosopher of the first century. WG owned George Long’s translation of The Discourses of Epictetus.

Pyrrho: Greek skeptic philosopher (c. 360–c.270 BCE). Otto relates an anecdote about him in R (130).

David Hume: Scottish skeptic philosopher (1711–76).

George Grosz: see postscript to the letter of 3–4 May 1947.

dum spiro spero: Latin, “While I breathe, I hope,” attributed to Cicero, and the motto of many families and organizations.

To Edith Gaddis

Mexico City

[April 1947]

Dear Mother—

I do hope this will be the last time I shall have to put upon you so. And just now am in a sort of confident spirit because I believe Blague has something to say, if I can write it. If not, believe me, there is little else that interests me, but I shall do something which will take care of me, and I shall not have to keep you living in this perpetual state of waiting to hear that I need something. And so I add, could you within another week or so send 25$ more? And that will be all. Believe me, if Blague is done it will be worth it—you will like it. And if I can get an advance things will be rosy. As I say, I have the outline done, just what I want to take place from beginning to end. And each scene clear in my mind. I have only written about 5,000 words, and plan 50,000, comparatively short—ap. 200 pages.

We want to leave as soon as we can sell the car &c, out where living will be cheap.

Believe me, it will be worth it—I have never felt so single-purposed about a thing in my life. The novel will be the best I can write. And as I say, if it doesn’t do, you won’t have to put up with this foolishness any longer. Davison likes it much, and is very helpful. Am getting sun, and even on 20¢ a day enough food, eating in the marketplace. A grand city, but without a job or tourist money, no place to stay. So have faith for just a little longer—it will work out. Thanks, and love—

Bill

To Edith Gaddis

Mexico City

15 April ’47

Dear Mother—

[...] You—and anyone—can usually be pretty certain, if you receive a letter of any length from me, that I am for the moment fed up with the novel. No offense—but, except for time we spend going marketwards for food—usually about 5 pm, the daily meal—or in the morning, for café-con-leche—I am here working on Blague. Of ap. 50000 words planned, I have 10000 fairly done—though now—tonight—must go carefully over all I have done, add wherever I can, clear up as much as possible—and even cut, wherever I use too many words—which is often. When I finish this part, am going to send it to Little Brown, where Davison’s father will see that it gets read &c. And with any encouragement from them perhaps I can finish it in a couple of months.

The newspapers down here—very anti-communist &c, are practically fomenting war—at the moment much about Mr. Wallace. And so I have the idea—which as you know I have had for some time—that war comes soon. And Blague must be done before that, concerning itself with Armageddon &c. So we go. [...]

I have just discovered a new brand of cigarettes—Fragantes, which cost 4¢—and here we have been paying 5¢! Wasting our $. Great cigarettes, though they are inclined to come apart or go out—and are quite startling first thing in the morning. Someday—I look forward to Players again.

We have been to just one film since here—Ninotchka, with Spanish subtitles. A wonderful, delightful film. Admission is about the same as in the States, around 60–70¢, so we are debating about seeing Comrade X now playing.

I had a silly letter from Chandler Brossard, who wants particulars on living here. We may get him down here yet! Also letters from others, keeping me up on NYC, which sounds absolutely dull. But a safe distance off!

If the novel goes, I have thought of coming up in August. Possibly July. I cannot think of the Studio being so alone, and we might have a good piece of summer.

As for living here—anything you are curious about? I have given you most of it, I think. And it does not vary. My mustache seems to have stopped growing, now hanging down the corners of my mouth. To work.

Love, Bill

PS—We are leaving for Veracruz this evening (Wednesday). Everything fine. Will still get mail from W.F. And probably be back here soon enough.

Mr. Wallace: Alfred A. Wallace (1888–1965) denounced Truman’s foreign policy in the New Republic (where he was editor in 1947), arguing it would lead to further warfare.

Ninotchka: 1939 film directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Greta Garbo.

Comrade X: a 1940 film derivative of Ninotchka.

Chandler Brossard: novelist and journalist (1922–93), WG’s roommate in Greenwich Village for a period. Brossard based a character on WG in his first novel, Who Walk in Darkness (1952).

Studio: a converted barn next to Mrs. Gaddis’s house in Massapequa, which WG (like Edward Bast in J R) used as a work space.

To Edith Gaddis

Mexico City

24 April”47

dear Mother—

A week in Veracruz. I could describe it to you now, here, in many pages—the incidents, &c., the changes in plans. But I must mention the trip. We were told before leaving that if we took one road we should go over the ‘biggest god damn’ mountain in the world’. I believe we did. At night. Do you remember driving from Hicksville home one night after the movies, fog so thick and we going 15mph, and did not speak for two days after? Imagine it like that, except a cloud instead of fog, heavy rain, roads of such incredible twists I shall have to draw them for you, and hills so steep that the heavy Cord, even in gear and with brakes, wouldn’t stop. Honestly, it was wild. We went with what later turned out to be some sort of young confidence man, I believe, with a number of angles to work on us. The car finally sold, and at a pretty low price, but glad to get it done—after that ride, it really isn’t worth much. The young man, Ricardo, was working so many deals that we finally escaped quickly. I wax to be captain of the boat his father owned, which sounded jolly, but never saw the boat. He had a good place with one pleasant enough room bed &c., and behind it a shanty affair with mud floor where we slept. Down in the rather crowded residential section, near the market—residential for chickens, pigs, dogs, unnumbered barefoot children, radios, people. The noise at night!—cocks crowing, then burros and jackasses he-hawing, turkeys, dogs and dogs; and when eventually the sunrise put an end to the fracas, everyone leapt from bed and turned his radio to a different station. It never stopped. It is probably going on right now. I shall tell you, someday when I have more breath, of how I entertained hordes of tiny ninos (that is their charming word for children) by reading bible lessons in Spanish, putting lighted cigarettes in my mouth, swinging them about on my fingers. Or of how I entertained the (sic) adult population, after meeting the man who owned the entire market—a remarkably tremendous place—and he almost as much so, proportionately, we sat across the table from each other, and after proving myself able to mouth bits of his language, a 5-gallon jug of pulque was brought out. We drank a glass (Salud!), then he poured me another, &c., until soon he was pouring me glasses and then drinking with me from the jug. When that was gone (a litre is about a quart) we had some tequilla, to keep spirits up, and beer to make it a real comradeship. Entertained the populace, as I say, finally by falling off a rather vigourous streetcar. Huge joke. I think if I had actually split my head they would have died of laughter, but I can’t go that far with them. They had enough fun as it was. Believe me, I am fine now.

And Mexico City looks good. I arrived to find quite a sheaf of mail from you, and shall try herewith to answer and straighten things out as they come. I gather from the tone of them that you have been having it rather rough, and I can imagine, and wish I were there to help you along instead of here, to keep you in a state of such running about.

First, immediate plans. We have just returned from the ‘shopping district’, carrying (picture this) two saddles, bits,—all the equipment for the equestrian. Bill has got himself a pair of boots, and we are ready to be off immediately for some sort of rustic nowhere. I cannot quite make out when you sent the boots and spurs. They are all that count really; the gabardine shirts would be fine, but don’t really need them; hope you did not bother to send clean white shirt, no use for it; also the watch, which I didn’t mean for you to try to send, but if you have don’t worry about it; the machete doesn’t matter, very cheap here; don’t for heaven’s sake worry about small-pox, no mention of it in our circles here; many thanks for NCB, but I don’t see that you needed to bother, I never have enough money to carry on with banks, and as you shall see in the future don’t plan to need a checking acc’t; Look, many many thanks for sending the money (25$ WU April 10th, and just rec’d on return from Veracruz Thursday 25$ WU) But please don’t send more money, it only leads us to confusion, and trouble for you. I don’t need it now at all. We have plenty to get off from here for the sticks for a while. Honestly, I will let you know when I need it. I hate to sound excited about it, but when I need it I can let you know and you can always wire it just in care of the Western Union I wire from. OK? I am just tired of envisioning things like NCB machinations, that’s what I came off to Mexico to get away from. So let’s just leave it, I’ll let you know if and when. OK?

The apartment: I really hope to not want it this fall. Here’s what my hope is. To get out of here as soon as possible on horses to compleatly uninhabited country, for about two months, keeping in touch with Wells Fargo here or giving you an address so that we may correspond, but away from city machinations, all this business. Then, get back across Mexico to an eastern port town like Veracruz, Tampico, &c., end of May or early June or middle of June. From that port, start home, either working my way on a boat (talked to sailors on freighters in Veracruz, who say such things are still done), or (this is the only time I may need money) getting some sort of passage, and hoping to get back to NY late in June. Then coming to Long Island and working on the novel there this summer. How does that sound? At that point, of course, much depends on how the book comes along. But in the fall, especially if I have got any sort of money out of the book as a start, to leave NY again and go heaven knows somewhere. I cannot plan for that of course. And so don’t want to say, dump the apartment. But feel sure enough about it to say, if there is anything brought up involving business about a new lease before I get back, to let the place go. I don’t see great future for me in that old place, do you? Good if I could get back in late June and get books &c. together, so don’t worry about such things until then. Many thanks for the addresses, we’ll use them if there is any occasion.

Now. I hope that all of this, instead of unnerving you, has given a clear and rather bright picture. Honestly, I can see from your letters what a time you have been having, and feel like a fool having added such things as a machete for you to worry about. Needless to say how good I feel about the Halls, Mary, &c., all they have done. And pray, as they do I believe, for the day you can relax. Just relax. Anyhow you can about me now for a while. Or if you would rather get excited than relax, take a look at the enclosed pictures. In the large cabinet portrait, meet Mr Robert Ten Broeck (Bill) Davison. We are walking a main street in Mexico in the morning after coffee, not, as you might believe, discussing the missionary problem in Bengal or proofs of God. He is saying something rather violent about the cigarette he is holding, which has just gone out. I am reacting to his language. The beards, as you see, are not too exciting as yet. We do look ratty, but both are delighted with the picture. Also, a blurred indication of how we slept on the way down, unfortunately double-exposed, but if you look, I am in a sleeping bag, on my back looking up, with a cigarette-to-mouth, and above my head is the little dog we got in Louisiana (and lost eventually in Mexico). Me sitting down is me sitting down on the roof of the hotel Casablanca, where we call home, looking rather small-headed. The dog (named, fondly enough, ‘Old Grunter’) appears again in picture taken on the highway on the way down, cradled lackadaisacally (spelling!) in my arms. Great shot of the car. To top things off, a rather dull shot of a river from highway miles above. [...]

Off we go, into the hills. Davison for the first time on a horse. The wh[o]le thing should be fine, and whether the novel prospers (believe me I am going to try to help it do so) it will be healthful. I shall write, and get mail from W—F—until I let you know differently, though obviously for the next few weeks or two months letters farther apart. Believe me, we are fine, see no reason why things should not go off as planned, at least until I see you in the summer. My love to Granga, hoping to see her too.

Love—

Bill

PS Remind me sometime to tell you about the fox we had in Veracruz. Now there was a pet!

NCB: National City Bank.

Halls, Mary: Charles Hall, an antiques dealer, and Mary Woodburn, John Woodburn’s wife and a close friend of Edith.

Old Grunter: a name WG used for family dogs.

To Edith Gaddis

Mexico City

[29 April 1947]

dear Mother—

I never do a thing, or if I do it immediately, it is wrong. So after that lengthy piece I mailed you this am concerning three suitcases being sent you, most of it is wrong, as I foolishly sent it before the bags. [...] If a sloppy package should arrive for you from Houston, Texas, it will be my handsome treasured Brooks Bros hat, being sent by the garage mechanic, since it was in a restaurant which was closed the night we left, and I couldn’t retrieve it. I hope he gets around to sending it; if so, could you rescue it, and have it cleaned and blocked?

Then there are some books I shd appreciate your getting, sometime between now and June or July:

A Study of History by A. J. Toynbee Oxford Press 1 volume abridgement.

Aspects of the Novel by EM Forster Harcourt Brace $2.50

Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse Henry Holt $2.75

The above are recent, in print. This below have no full information on, but may be available.

The Golden Bough by Frazer (well known book) or Frazier—a book on anthropology.

These are little paper-bound things, should be available, perhaps at Brentano’s, or some college textbook place; published by The Open Court Publishing Company, La Salle, Ill.

The Vocation of Man by Johann Gottlieb Fichte 50¢

St Anselm: Proslogium, Monologium, an Appendix on Behalf of the Fool by Gaunilon; and Cur Deus Homo. (this is all one)—60¢

The first two are most important to me, should be readily available (though the Forster is reprint, may be sold out quickly, and I would like to go over it carefully—for obvious reasons). So thank you, hopefully in advance.

We are now (29april) on the eve of leaving for life in the woods. Can[n]ot imagine what will turn out, but don’t fear: we have dysentary pills, all sorts of things, including horse equipage, blankets &c. So don’t for a moment worry. It may last a week or two months, we hope to reach Tampico eventually.

Have had no word from you on how my spending the summer in Massapequa sounds. Because though I am working on my novel, and will these coming weeks, I know I can do best out there, quiet summer—regularly tasty food (how I dream of it!). It has taken me all this trip and time to figure it out, now it needs writing, and not the sort I can manage sitting on the edge of a bed or a pile or rock. I hope the idea suits you—I picture it as being a good regular well spent couple of months, and we could have a good summer out of it.

Think of nothing else now, will instruct Wells Fargo to follow me about, and certainly don’t worry if you don’t hear for a week or two—simply mean we are not near a PO. Mexico is a pretty raggedy land.

Love, Bill

A Study of History: D. C. Somervell’s 600-page abridgement of the first six volumes of Arnold J. Toynbee’s classic study was published by Oxford University Press in 1947.

Aspects of the Novel: first published in 1927.

Steppenwolf: Hesse’s 1927 novel about the outsider nature of the artist was translated into English in 1929.

The Golden Bough: Sir James George Frazer’s multivolume survey of magic and religion was published in abridged form in 1922, the edition WG used for several passages in R.

The Vocation of Man: a philosophical work first published in 1800; in R Otto quotes “Fichte saying that we have to act because that’s the only way we can know we’re real, and that it has to be moral action because that’s the only way we can know other people are. Real I mean” (120).

St Anselm: Piedmont-born English theologian (1033–1109); WG named a major character in R after him, and quotes him a few times in the novel (382, 535). The edition WG asks for was published in 1939.

To Edith Gaddis

Mexico City

[3–4 May 1947]

dear Mother—

Just a few words to let you know the change of plans. The horse business in Mexico didn’t work out, simply because it seems impossible to buy horses. One was offered, at 120$! Twice the price. So D—, still hell-bent on riding, has the fancy of going somewhere in the Southwest US. I care little at this point, having had a grand Mexico, which is to be topped off Sunday by a bullfight. D. doesn’t care about it, but I have persuaded him it is a spectacle worth seeing. So we stay over and leave Monday for Laredo, thence I know not where, care less, so long as there is a place for me to lie down in my wretched bolster at night and sit up at this machine by day. All of which really alters nothing, I still plan on returning in June, we can set the studio in order, and I hope for a well-regulated summer in which Blague will either be done or collapse. With all of our bumping around recently I have had no chance to get at it, and feel guilty, limiting myself to scraps of notes on paper. Anyhow I shall see you in June, and meanwhile write you when we get some sort of flavourfully-western address, if we chance to settle near a stage line. [...]

Little more of note. My beard looks at the point where it will not be very edifying, even in another month, and need a haircut, the last having been what seems months ago in New Orleans. Everything fine and in order, life is great, will keep you posted. I have been on the roof, my usual quiet refuge for working on the novel; but today, impossible. It is la Dia de las Cruces—Day of the Crosses—and like a battlefield. The air absolutely full of explosions, natives sending up fireworks. Became downright dangerous, as well as disconcerting—felt like a foreign correspondent reporting a Black and Tan fracas so am back in the room.

My only Mexican expenditure, souvenir, and that through the munificence of D., a beautiful little pair of silver cufflinks with my old design which I am so fond of, and so neatly done. I am quite content, happy. Hope you are similarly so, and will write.

PS —In view of past mixups, I have have held this letter over until Sunday night, just before we leave simply to tell you that I have had two (2) wonderful steaks—filets—today, and the bullfight was grand.

Here is another book:—Being by Balzac, it may not be readily come on in modern book stores. But if so, if you should be able to come on it, how much appreciated. It is Zeraphitus by Honoré de Balzac. If not, don’t trouble about it.

Love, Bill

PS

It is very late, I have been lying awake for some time, as I often do, thinking about—or rather being persecuted by this novel. With D—asleep I cannot make lights and notes, or work. At this point things usually get pretty wonderful, as you know about such possession. Anyhow, do you know of a German artist-illustrator named George Grosz? I know this is pretty excessive—he is well-known, brilliant &c (so this is rather between us, if it comes to naught, as it probably will)—but I have long liked his work, serious painting and cartooning—(he has done much satirical drawing on recent Germany)—but I want to try to get him to illustrate Blague. If only it could be done. His drawings would be exactly what I want for it—really want to complete it, as it were, besides obvious commercial advantages. He has written a book called A Little Yes and a Big No. It costs $7.50. If it could be managed, I should love to have it when I get back—and you would get a kick out of looking it over I know. If possible I want to show him my manuscript this summer (I think he lives in N.Y. now)—and try. Meanwhile, if it can be done not to[o] strainingly, how I should appreciate his book.

PS If you can and do get any of these books—not to be sent—I want to read them this summer in Massapequa. And thanks.

Love,

Bill

Black and Tan fracas: a British-supplied police force (named after the colors of their uniform) sent to Ireland in 1920 to help the Irish constabulary quell uprisings.

Zeraphitus: that is, Seraphita (1835), a metaphysical story by the French novelist.

George Grosz: German artist (1893–1959) who emigrated to the U.S. in 1933. His autobiography, A Little Yes and a Big No, was published by the Dial Press in 1946.

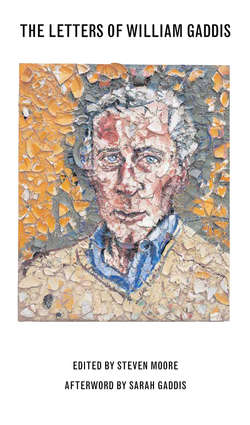

Ormonde de Kay and WG at Donn Pennebaker’s apartment in Greenwich Village, late 1940s. (Photo courtesy D. A. Pennebaker)

To Edith Gaddis

[WG returned to New York, but five months later he decided to leave again (the night of 28 November), this time for Panama “to launch my international news career” at El Panamá América, a bilingual newspaper, as he wrote thirty years later in his brief memoir “In the Zone” (New York Times, 13 March 1978, reprinted in RSP 33–37). It didn’t work out. From this point on, WG begins sometimes signing his letters W (for Willie) rather than Bill. But he lapsed to neglecting to date his letters, so most are supplied from postmarks.]

Hotel Central

Plaza de la Catedral

Panama City, Panama

[late November 1947]

dear Mother—I had intended to write you a goodly letter about the fantastic business of being in 6 countries in one day, but by now the fantasy has got out of hand. I was met at the airport by four white-coated young gentlemen, escorted to a waiting Lincoln, and driven to my hotel, an establishment where I have a room about the size of Madison Sq Garden and a private balcony overlooking the park. Then off for a few drinks and courtly conversation. Apparently I shall have a job, and no kidding, on this paper at 350$ a month; I am to have breakfast with the owner in the morning.

Fantastic.

That’s all.

This is simply a note to let you know we are all alive, and I am breathing heavily, acting sophisticated and trying to carry on.

It is splendidly hot, and so am I, inside and out. When breathing begins to come more naturally again, I shall write.

Love,

W.

To Edith Gaddis

[The new novel WG mentions below, initially called Ducdame, eventually became The Recognitions.]

Panama City

[December 1947]

Dear Mother—

Here is one of those letters which makes it worth your while to have me 3000 miles from home. Perhaps not. I don’t know. I am quite confused.

I have just come back from coffee with a man named Scott, who is managing editor of the paper. He is very kind, and about to ship me off to a banana plantation. Roberto Arias—whose father and uncle are currently running against one another for the presidency—owns the paper. But the de la Guardia faction, my guardians, have rather put it upon his shoulders for my employment. He too is very kind, I had a pleasant lunch with him and his wife in their penthouse a day or so ago, and Roberto tells Juan Dias that I can have a job as a feature writer on the paper. Mr Scott, the kind NewZealander, finds the paper quite to his liking as it is. We go around and around in circles, there also being a matter of 225$ to be paid the P—government if I hang on and take such a job. Eh bien. With all of the Latin fooling around, bananaland sounds like the best bet. Everything here, in the city, is high; I have moved from the apartmento overlooking the park to a smaller, more airless cubicle, at 2$ the day. They give me no ashtray or (my favourite) cuspidor, so I must toss cigarette stubs on the floor. Not very pretty, but home.

At the moment I am waiting for a cable from somewhere to see if the Chiriqui Land Company wants an overseer. Imagine! Stalking through the jungle (of course all of my clothes for such a life are safely in Massapequa, as usual), and Me, who as moments go by takes a dimmer and dimmer view of bananas, telling hundreds of natives what ones to cut for shipment. The whole thing as fantastic as it seems always to turn out. But I am quite pleased.

The city is all one could ask, teeming with people and hot as it can be. There are occasional nice places where one could sit down and work, but I think that even with a comparatively substantial salary (Roberto mentions 350$ a month) the money and time would be gone as soon as it came, and I have honestly had enough of high life and sophistication for one season. From descriptions of bananaland, there is only the heat of the jungle, work to be done during the day, and the evenings and nights free. You can see, it sounds like a good place to work. The salary is pitifully small, but I gather one’s needs are taken care of, and it is possible to save something each month.

I have started the plans for another novel. It all sounds so very possible, to spend a stretch on the old plantation, healthful outdoor life drenched with sun, and work on a book. And if the book does not work out, at least I should be able to escape with my life and leathery skin and enough money to get back to the states and figure out another immediate future. I hope that all this does not distress you. It shouldn’t; at least for myself it looks good.

A good deal of my time is spent walking. I walk miles around the city alone, just looking and thinking. Then back to this palace to take off a wet shirt. I have still as little sympathy for the spanish language, and know just enough to be able to struggle through meals and get directions when I get lost, which is often.

You remember Davey Abad, the ex-prize fighter whose nightmares I shared on the ss West Portal some 6 years ago. I stopped in at a cantina a few evenings ago for a bottle of cervesa negra, fine dark beer, and there was Davey collapsed in a corner. He is taking cards at the gambling casino in the hotel Nacional, very ritzy, and I spent a pleasant hour or so recalling old times with him. Then I went into the casino and watched one man lose 100$ betting on the black on the roulette wheel—just like that, in two minutes, five spins, every number came up red, he with 20$ each time on the black—and a sad shattered American woman writing out 50$ travellers cheques like crazy to keep up with her losses. Fascinating, of course. The number 17 came up five times in twenty minutes, and I was fearfully tempted—but escaped quietly.

Everyone is kind. Strange to think that I have been here less than a week; I feel that the winter must be past in NY, and spring opening on LongIsland, that I have been away that long. But I gather that if the Chiriqui Land Company needs honest and competent (!) work done that it will seem years before I can manage to stroll into Brooks Brothers next fall and give them 47$ for one of their attache cases, and end this business of carrying papers and soap and a shaving brush in my pockets.

Again, thanks for so many things. I am getting on well, eating far more regularly than I ever managed in NY, &c &c. This address will reach me, I shall tell them to forward if the jungle calls.

Love

W

Roberto Arias: Panamanian lawyer (1918–99); his younger brother Tony was at Harvard with WG. Arnulfo Arias was first declared the loser in the 1948 presidential election, then declared the winner and held office from 1949 to 1951.

Juan Dias: spelled Diaz in a later letter, otherwise unidentified.

Chiriqui Land Company: a Panamanian fruit and vegetable vendor, a holding of Chiquita Brands, and still in business today.

To Edith Gaddis

Panama City

Thursday [December 1947]

Dear Mother—

Just a note to say I have your letter, and thank you. Honestly, it seems months since I left.

Also, best to call father and thank him for the Christmas present sentiment, but I think it somewhat dangerous to send anything here, with my plans as they are. This place will certainly forward mail, but you know the inter-American trouble that can happen with packages! Tell him I shall write.

Plans still uncertain—I hope the bananaland deal works out; it is the sort of exile I need. Am working hard at new novel—it is to concern vanity. I think I can write with some authority!

Well, you certainly sound like you are leading New York high life! Good—I do want you to have a good winter. No need to worry about sending me money—unless I have to pay my way out of bondage from the Chiriqui Land company!

Love to Granga, and you.

W.

To Edith Gaddis

Panama City

[28 December 1947]

dear Mother.

Another bulletin from the front. This one says that the Chiriqui Land Co doesn’t need the services of this old banana man. This old bananaman was pretty discouraged until today, now he is no longer discouraged but a bit alarmed. He has got a job with the canal, doing some kind of out-door work, something like helping overhaul a lock, whatever that is. I hope that you are not concerned that the fine education you gave me is producing nothing but a hemispherical bum, (let’s say vagabond, sounds nicer), and one who even in his better moments can at best push a wheelbarrow. (I must interrupt here and say that I would rather push a w-b- and have my mind to myself and be able to laugh when I want to or spit or quit than be standing agued and wet-footed in a 40$ a week publishing-house in my favourite city, wasting the only treasure I have, the English language, constantly being angry with things which are wasteful to be angry at, &c &c, you know.) [...] More often each day I am taken for something left here by a boat, which has cannily gone on without an undesirable member of its crew. Eventually I hope to send you my measurements and a portion of my earnings so that at your pleasure you can go to Brooks (I don’t believe that they do have my measurements, they may) and have them send me one of those natural-colour linen suits they are hoarding on the 2nd or 5th floor. They are around 35$, and I find I would have to pay at least that here, without even getting the Brooks Brothers label, instead a suavely pinched-in waist which passes for fashion among these vain people but isn’t quite what I have in mind as chic. And one might as well be chic if it is all the same price. Also it advances the chances of free meals, refreshments, and similar necessary vanities among the ‘set’ which I enter on occasion (occasion being the slightest hint of an invitation).

The two young gentlemen, Juan Diaz (a judge) and Guiellmo de Roux (an architect) continue to bear with me, and Sunday we motored again to the 50-mile-away beach and plundered the Pacific for all it was worth. I have a fine letter from Jake, whose plans for departure are practically realised, and I’m delighted; also one from Gard[i]ner, whose talents will never fail to arouse something akin to jealous envy in me. [...]

Love, W.

PS I have written to Father, a letter of news, greeting, and warning that perhaps it wouldnt be wise to try to send a gift right now.

Guiellmo de Roux: that is, Guillermo de Roux, a prominent American-educated architect.

To Edith Gaddis

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

[9 January 1948]

dear Mother.

Wouldn’t it be nice if I could write a good novel? Well, that is what I have been trying to do all morning. Now it is near time for lunch, and then my presence and talents are required at the Miraflores lock until 11 pm, to take up with my crane. And coming in near midnight after that leaves me not wanting very much to jump out of bed in the morning for the great prose epic that is daily escaping from under my hand.

This is to thank you for the attaché case attempt—and to say that it’s hardly a necessity. Because for the writing, I don’t think I have anything really worthwhile carrying in one yet. I think the attachécase will just always be one of those distant beautiful images that lure us through this life and keep us believing that our intelligence is worthy. Meanwhile don’t trouble about it. Perhaps, if in the summer I can get up there with something worth showing a publisher, one of the objects of (instant) beauty will be mine, and I shall have something worth carrying in it. As you may gather, I am not in very high nor triumphal spirits.

I enquired at the post office. There is no duty on anything sent for the recipient’s personal use. If you get in touch with Bernie (PL81299) I’d like to know if he’s in NY. or what. Also he has a small alarm clock, a little green one—and I need an alarm. Could you find where he got it? And if you could get and send me one like it?

Also badly need a haircut. I borrowed 10$ from Juan Diaz, my kind friend, so am seeing through quite well. Sorry about the trouble over the ’phone call. I don’t understand about the 30th of Dec. call—I was at the ’phone station from 850 until 930. They’re all insane down here anyhow. But I’ll call in a few weeks, after I get paid, just for the fun of it.

Love,

Bill

Bernie: poet, critic, and artist Bernard Winebaum (1922–89), a Harvard/Village friend of WG, worked briefly in the advertising business (and wrote book reviews for Time, Alan Ansen told me), then spent most of his later life in Athens, where he owned a restaurant.

To Edith Gaddis

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

[12 January 1948]

dear Mother.

Well. I have been thinking about Mrs —, whatever the numberscope lady is—with something like horror. She has been rather remarkably right on the whole. But, she says January 6th to start new work which will carry through until September 19th. Does she mean spending 8 hours a day in the bottom of the Panama Canal?

The difficult part of such an existence is that having done a day’s work of this nature, one is very tempted to do as the other men, who, with perfect right, feel that they have earned their place for the day, and relax. But I cannot. Infrequently the library here keeps me in good reading. Yesterday I had 2 plays and one novel, much for thought. And continue at work on my novel. I cannot work on it as I would—to sit down at the typewriter when I wish and write—because the machine makes so much noise as to disturb resting neighbors. So I try to write it in longhand, and to make continuous notes far in advance.

And then suddenly realise, in the midst of all this thought, here I am 25 and my education is just beginning. Honestly I wonder what I “studied” at Harvard.

I do hope to save enough here to be able to afford to go back—not necessarily to Harvard, preferably abroad—and study. And if I can do that and finish a credible novel by the fall it will be splendid. Oddly the things I want to study are not things I did at Harvard. Philosophy, comparative religions, history, and language. Well God knows often my hands are so tired from handling cables &c. that I do not do very well with this pen.

This is just an outburst—and regard it as such; suddenly like the whole bourgeois soul being terrified at time’s passing, most especially furious to watch any of it wasted, as often the Canal seems to do. So much to learn and to think, no time for indulgences. I feel possessed. Soon will write a better letter.

Love,

W.

To Edith Gaddis

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

[15 January 1948]

dear Mother.

Many thanks for your letter. I can’t do anything else now—purely nervous temper—so shall try to write you. I mean I can’t work. It is 1030 in the morning, I am to go out to work at 230—and somehow can’t write. Largely this restriction on the typewriter and not being able to feel free and unrestrained—difficult anyway in the morning—and I can’t work. I don’t know what the right conditions are or even will be. Now I have the novel outlined, quite definitely (and continuously) in my mind. But for writing it that is the work. I am continuously upset, short tempered with most of the people I run into. I think what I shall do is work on here for about 3 more months, meanwhile reading, note-taking, trying to write. By then I should have saved around 300$. Then get a job on a boat going out of here for a couple of months. Then with a little money be able to do just as I wish. I don’t know. I can’t work unless it is in a place where I can come in at any hour of night put on lights and use the typewriter. We shall see. Meanwhile time is not being wasted I think because I am reading and thinking—sometimes with febrile excitement as a few days ago a play by Sartre called Les Mouches and also am making the money necessary to human dignity or at least solitary existence which is promised.

Of course letters from N.Y. excite me. I had a good one from Connie yesterday—and yours today with mention of Bernie &c. &c. You know he is rather simple, not a great mind—or at least not a good creative one (I am afraid, and he wants to be a good novelist, that is his tragedy, the more so since no one will see it as tragedy—can’t take him seriously for long)—and I know it is simply indulgence to myself that makes me like to be with him, but I do miss him he is so kind, and there are few of those.

The only New Orleans person I can think of is Fischer Hayes. God knows what he is doing with a magazine—it couldn’t be a very brilliant one. I heard he had married. Anyhow whatever the circumstances I should like to publish that story almost anywhere. So here is the next of the endless string of favours I ask of you. The name of the story—considerably rewritten since Hayes saw it—is “The Myth Remains.” You may remember reading it. It is in Massapequa, and in a manila envelop with other stories, God knows where. But probably either on or in my desk or on the balcony. Not among the envelops on the landing, those are Chandler’s (things I wouldn’t be caught dead writing!). If you could pick it up next time you are out there, and meanwhile I shall hope to hear from whoever this New O—person is and write you.

Just before picking up your letter this morning I sent one off to father—brief cheery I think newsy bit. The prospect of publishing anything excites me as always. Bad business.

Now I remember the name of Bernie’s clock is Thrill. And I should appreciate your sending me one very much. Yes the place is Tourneau—Madison at about 49th. (Lord how I miss New York!—You see what I am occupied with now is this whole business of the myth—tradition—where one belongs. And while disciplining myself to behave according as my intellect teaches me—that we are alone, and all of these vanities and seekings (the church, a wife, father &c.) are seekings for some myth by the use of which we can escape the truth of aloneness. Poor Bernie, he won’t accept it, nor Jake that more successfully. But that is the whole idea (message) of my novel. I’d rather talk with you about it, the letter is so unsatisfactory but I have to write it down. I am afraid my letters are getting worse, also handwriting.

Again many thanks for the check. And so happy to know you are having the pleasant (pleasant hell it sounds hilarious) winter you deserve.

Love,

Bill

Les Mouches: 1943 adaptation of the classical myth of Orestes and Electra avenging the death of their father; published in English translation by Stuart Gilbert in 1946 as The Flies.

Connie: probably Constance Smith: see note to 4 May 1948.

Fischer Hayes: called S. F. Hays in the next letter, apparently the painter “Sam Hays” mentioned earlier (9 March 1947).

Chandler’s: Brossard’s stories were however being published in little magazines at this time.

To Edith Gaddis

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

[19 January 1948]

dear Mother—

Just a note to say I have heard from S. F. Hays, with a prospectus of the new magazine, which looks highly creditible. And to entreat you, on your first trip to Massapequa, to pick up that M.S.—“The Myth Remains”. Now it must be in a large envelop with other stories, paper clipped. Not loose in a drawer—such might be an earlier version, and not to be shown. One of the other stories is “In Dreams I Kiss Your Hand, Madame.” Don’t bother with the other stories. I think the envelop has a large number 1 or I on the outside, and addressed to me from Harper’s Bazaar—almost certain it is on top of the desk. Will you please send it to:

Miss Cornelia P. Claiborne

153 East 48th Street, N.Y.C.—and meanwhile I have written her a note asking her to return it to you if she doesn’t want it.

Please pardon the outbursts I’ve been sending you. Now things are getting settled, I have a better system of time for myself. Coming in at midnight, I work on my novel until about 4 am—then sleep late. Tell G. S. B. to keep his shirt on. I am working hard, hope to have some money too when I show up there in the summer.

I am even drinking hot-water “lemon” juice when I get up! And have many good books from the library, and two new pairs of pants (not Chipp). The job isn’t bad, except for the often hours of inactivity which madden me, any wasting of time now does. But the new novel, with incredible slowness, pieces itself together. And worthwhile thought is rampant. If I can stay with this life for a few months, perhaps I can show up with first novel draft, but not dependent on its success—so if it doesn’t go I’ll have money next fall to go abroad and study and continue to write.

Now it is past noon—I must make my little lunch (ham sandwich, peanut-butter sandw., and onion sandwich) (I keep the food in a drawer of my dresser) and be off for the breadwinning.

Love to you,

Will

PS. Another favour, if this incarceration is to last. If you could put aside the book review sections of the Sunday Times, and send them to me every 3 or 4 weeks, I should appreciate it greatly. Haven’t seen it for so long, and get curious about current state of “literature”.

“In Dreams I Kiss Your Hand, Madame”: an early version of Recktall Brown’s Christmas party in R (II.8). It was posthumously published in Ninth Letter 4.2 (Fall/Winter 2007): 113–17, and reprinted in Harper’s, August 2008, 29–32.

G. S. B.: unidentified.

Chipp: a men’s clothing store in Harvard Square and later in Manhattan.

To Katherine Anne Porter

[American short-story writer and novelist (1890–1980). WG wrote to praise her essay “Gertrude Stein: A Self-Portrait” in the December 1947 issue of Harper’s. (It was retitled “The Wooden Umbrella” in her Collected Essays.) He would write two more letters to her in April and May of 1948.]

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

21 january, 48

My dear Miss Porter.

A friend at Harper’s was kind enough to send me your address—I hope you don’t mind—when I wrote him asking for it, in order that I might be able to tell you how much your piece on Gertrude Stein provoked and cleared up and articulated for me.

To get this out of the way, I am one of the thousands of Harvard boys who never learned a trade, and are writing novels furiously with both hands. In order to avoid the mental waste (conversation &c.) that staying in New York imposes, I am here working on a crane on the canal and writing the inevitable novel at night.

I have never written such a letter as this—never felt impelled to (but once, in college, an outburst which I fortunately did not mail to Markova, after seeing her ‘Giselle’) —But your piece on Gertrude Stein—and your letter that accompanied it—kept me occupied for three days. And since I have no one here to talk with about it—thank heavens—I presume to write you. Having read very little of your work—remember being greatly impressed by ‘Pale Horse’—so none of that comes in.

How you have put the finger on Miss Stein. Because she has worried me—not for as long nor as intelligently as she has you certainly, but since I have come on so many acclamations of her work, read and been excited and cons[t]ernated, and not realised that emptiness until you told me about it. I read your piece just nodding ignorantly throughout, agreeing, failing to understand the failure in her which you were accounting. Expecting it to be simply another laudatory article like so many that explain and analyse an artist away, into senseless admiration (the kind Mr. Maugham is managing now in Atlantic). Toward the end of your piece I was seriously troubled—how far can a writers’ writer go? (V. “She and Alice B. Toklas enjoyed both the wars—”) —until I found your letter in the front of the magasine. Then I began to understand, and started the investigation with you again. Thank God someone has found her defeat, and accused her of it. And it was a great thing because it should teach us afterward places where the answer is not.

Certainly she did it with a monumental thoroughness. Now “Everything being equal, unimportant in itself, important because it happened to her and she was writing about it”—was a great trick. And: “her judgements were neither moral nor intellectual, and least of all aesthetic, indeed they were not even judgements—” which in this time of people judging people is in a way admirable. But that her nihilism was, eventually, culpable—and that her rewards did finally reach her, “struggling to unfold” as she did, all wrong somehow and almost knowing it. Her absolute denial of responsibility—and this is what always troubled me most—made so much possible. And how your clearly-accounted accusation shows the result.

It must have been a fantastically big talent—and I feel that we are fortunate that she used it as she did, teaching by that example (when understood, as your piece helped me to do)—for in our time if we do not understand and recognise the responsibility of freedom we are lost.

I should look forward to a piece on Waugh; though mine is the accepted blithe opinion of “a very clever one who knew he was writing for a very sick time.”

Thank you again, for writing what you did, and for allowing this letter.

Sincerely,

William Gaddis

Markova [...] ‘Giselle’: Alicia Markova (1910–2004), English ballerina, known for her starring role in Adolphe Adam’s ballet standard Giselle (1841).

‘Pale Horse’: in Porter’s short-story collection Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939).

V.: an old scholarly abbreviation (vide: see) that WG occasionally uses.

Mr. Maugham: W. Somerset Maugham: English novelist and playwright (1874–1965). In 1947 Maugham began publishing a series of appreciative essays on classic authors like Flaubert, Fielding, Balzac, et al.

your letter: Porter explains that she has read virtually all of Stein’s books and that Stein “has had, I realize, a horrid fascination for me, really horrid, for I have a horror of her kind of mind and being; she was one of the blights and symptoms of her very sick times.”

Waugh: Evelyn Waugh (1903–66), English novelist (see letter of January 1949). Porter writes in the aforementioned letter in Harper’s that long ago she read Waugh’s Black Mischief (1932) and felt “that he was either a very sick man or a very clever one who knew he was writing for a very sick time.”

To Edith Gaddis

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

[23 January 1948]

dear Mother—

Thanks, thanks again. And for having been so good as to take care of June Kingsbury. I must write them a letter. But can’t think of them at the moment, somehow makes me nervous to do so.

If your letter sounded lecturish certainly it was warranted by the outbursts I’ve been sending you. For which I apologise. I think I am getting hold now: the job, though still at times maddening when I am unoccupied, goes on with a minimum of difficulty. And the novel (in the most excruciating handwriting you have ever seen) is now two unfinished chapters, but I think good, and am comparatively happy about it—when it goes well I am fine, when not; unbearable. A black girl in the place where I eat occasionally accuses me of looking “vexed”—which in this West-Indian dialect means angry. So I tell her I’m vexed at the small portion she has put on my plate, and she tries to make up for it.

Two good letters from John Snow, to which I sent a rather excited answer—he probably thinks me insane by now. Also Eric Larrabee at Harper’s sent me the address of Katherine Anne Porter, a modern writer of some repute, and I have written her to say how much I enjoyed her piece on Gertrude Stein in the recent Harpers. Never done such a thing before, but that article certainly warranted it. Correspondence a good thing, though even it often seems a waste to me.

Please excuse my haste—my “lunch” (a munificent affair—one ham-cheese, one onion-cheese, one peanut-butter-marmalade sandw., all made by my busy hands) hangs from the light cord, so the ants won’t get it—and I must pull it down and be off.

Love

Bill

June Kingsbury: wife of WG’s Merricourt’s headmaster.

Eric Larrabee: (1922–90), managing editor of Harper’s from 1946 to 1958; WG met him at Harvard.

To Edith Gaddis

Pedro Miguel, Canal Zone

[29 January 1948]

dear Mother.

I have got the clock. What a charming little thing it is! to have the onerous duty of rousing me from good sleep or a good book—and I am finding so many—to send me out to the enclosed scene. And many thanks for sending off that story. Yes, it is supposed to end as you quote it—heaven knows if it should or not—but I can’t tell now, it is none of my concern now the thing is written I am through with it.

The lemon juice is me trying to see if there is anything in this world or the next that will make or let my face be itself without those horrible ‘things’—and at the moment it seems to be working! though it may be simply that the life I lead is one of exemplary dullness and regularity. But I shall continue the experiment—Lord, if it is as simple as that, a lemon a day. I can hardly think so.

Each of my letters, you know by now, asks some favour of you. This one is less involved than many—a book which I can’t get down here. In fact you may not be able to in N.Y.—it being only recently out in France. The author is named Rousset; the title La Vie Concentrationaire or Le Monde Concentrationaire. You might try a store called Coin de France on 48th St, or Brentano; and there’s a good French book store on that Radio City promenade. Don’t give too much effort to it, it may well not be available. [...]

A splendid letter from Jacob—after so many of the talks, the scenes I have been through with him, what I have seen him go through, you may imagine how happy I am that he can write: “When I’m alone I’m more content than I’ve been in years . . .” not that I don’t watch him with some element of unChristian jealousy!

Your mention of my “plans” sounding “glorious” is somewhat disconcerting. I must confess, they do not at all hold consistent, even from day to day. The illusion of studying again—at Oxford or Zurich or Neuchatel—something which I allow myself to indulge occasionally. If when the time comes I can manage it, all the better. But hardly ‘plans’! At least I am (1) earning and saving (2) thinking reading and writing—which is not time wasted dreaming. The novel harrows me all the time, sometimes it looks all right, at others impossible. (The latter at the moment). It must take time and quiet writing: there is so much of desperation in it, that it cannot be written in desperation, if you follow me.