Читать книгу Trespassers? - Willow Lung-Amam - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

LANDSCAPES OF DIFFERENCE

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

LANGSTON HUGHES, 1951

IT IS MIDDAY IN FREMONT, California, one of the many suburbs sandwiched along Interstate 880 in the 40-mile stretch between Oakland and San Jose. From the highway, Fremont appears no different than many other communities that line the eastern edge of Silicon Valley. Like San Leandro, Hayward, Union City, and Milpitas, the suburb sprawls over a vast terrain punctuated by strip malls, tract homes, office parks, and an endless sea of parking. But if one takes Exit 22 at Alvarado Boulevard and meanders through the neighborhoods, a different scene emerges.

Just off of Fremont’s main artery stands the Islamic Society of the East Bay, a newly renovated mosque and school with gold and royal blue cupolas adorning traditional Islamic architecture. Less than a mile south 99 Ranch, the nation’s largest Asian American supermarket chain, anchors Northgate Shopping Center alongside an array of bakeries, banks, beauty salons, tea shops, and other mom-and-pop stores selling familiar products from many regions in Asia. Farther south, Sikh elders and multiethnic teens gather at Fremont Hub, a large shopping mall marking the heart of the city. Similar scenes can be found a few blocks away at Gateway Plaza, where Naz8 Cinema, the self-proclaimed first “multicultural entertainment megaplex in North America,” shows Bollywood films on eight screens daily.1

From the Central District, it is a straight shot along Paseo Padre Boulevard to Central Park, where Chinese American elders crowd the banks of Lake Elizabeth in the early morning to practice fan dancing, tai chi, and other martial arts (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Elders regularly gather beside Fremont’s Lake Elizabeth in the early morning to practice tai chi and other martial arts. A regular visitor claimed that the lake’s positive feng shui was a major reason for its popularity. Photo by author.

Nearby in the historic neighborhood of Irvington, ethnic enterprises, an Indian wedding hall, and various Chinese and Korean Christian churches have revitalized aging storefronts and strip malls. Across from the local elementary school, cars spill out of Vedic Dharma Samaj, a Hindu temple carved from the remains of an old Methodist church.

In the background, cows graze the steep sides of the canyon that overlooks the bucolic Niles neighborhood, the once well-known backdrop of Charlie Chaplin silent films. Today the scene includes the Gurdwara Sahib, said to be one of the most influential Sikh temples outside of India with over 9,000 members, as well as the Wat Buddhanusorn, a popular Thai Buddhist temple and monastery (Figure 2).2

FIGURE 2. Gurdwara Sahib, one of the largest and most influential Sikh temples in the world, was founded in Fremont in 1978. It serves as a symbol of the suburb’s rise as a major gateway for new immigrants from all over the world, especially Asia. Photo by author.

Mirroring the Wat Buddhanusorn across Quarry Lake, the Purple Lotus Temple and Dharma Institute is under construction on a sweeping five-and-a-half-acre campus, soon to be marked by eight-foot prayer stupas and a perimeter wall decorated with the names of Buddha, Buddhist mantras, and auspicious signs to welcome its visitors.

Abutting Irvington is the plush hillside community of Mission San Jose, where feng shui and Vishnu principles have been used to reorient and redesign high-end houses and even entire subdivisions. Ornate iron fencing, grand fountains, columns, ornamental gardens, and Buddha and Krishna statues adorn the lawns of the neighborhood’s many well-to-do homes. Chinese and Indian American elders push strollers along its twisted streets and gather at local parks to exercise, gamble, or simply pass the time while attending to their grandchildren.

• • •

Fremont may seem to be an anomaly in an otherwise staid and predictable suburban American landscape. Images of Ozzie and Harriet suburbs populated by White middle-class residents, postwar tract homes packed on postage-stamp lots, and sterile shopping malls dominate the scholarly literature, popular media, and public perceptions of suburbia to this day. These images remain part of the dominant American narrative about who and what are suburban.

The reality, however, is much more diverse and complex than these stereotypes suggest. Over the past several decades while many urban downtowns have experienced a resurgence of energetic White millennials and affluent seniors, the suburbs of the largest U.S. metropolitan areas have quietly emerged as home to the majority of their racial and ethnic minority, immigrant, and poor residents.3 For the past several decades, predominantly non-White and diverse suburbs have exploded, experiencing far faster population gains than central cities and majority White suburbs.4

The suburbs have, in fact, never really been the placid, homogeneous spaces that have so captivated the American imaginary. A growing body of scholarship shows that diversity has long defined the culture, landscape, and inhabitants of suburbia. Combating popular stereotypes and scholarly literature that tend to paint a uniform portrait of suburbia and exclude the contributions of non-White and non-middle-class groups, a host of cultural and historic studies attest to the diversity that has always comprised suburbia.5 In the past several decades, scholarship on the suburban poor, new immigrants, and racial minorities, among others, has shown that social diversity has become more the suburban rule than the exception.6

How has the suburban landscape been reshaped by its changing demographic profile? How have these “other” suburbanites made home and built community among suburbia’s parks, playgrounds, schools, shopping malls, office parks, and other everyday spaces? How have they remolded the landscape in ways that challenge stereotypes about suburbia’s built environment and its residents? If mosques, Buddha lawn figurines, and Chinese fan dancers still appear out of place in suburbia, it is in part because scholarship has yet to sufficiently show how diverse suburban inhabitants have reshaped the look and feel of their chosen communities.

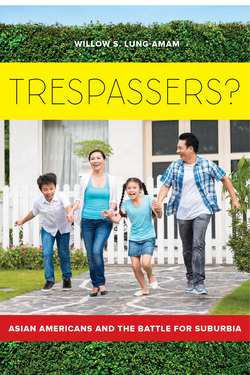

Trespassers? focuses on the processes of place making among Asian Americans, a group who have long existed on the suburban sidelines but are now at the center of its changing character. Asian Americans are the fastest growing of all racial minority groups in U.S. suburbs today. With 62% of all Asian Americans now residing in the suburbs of America’s 100 largest metropolitan areas, they are nearly as suburban as White Americans.7 This book examines the material products of Asian Americans’ attempts to build suburban communities to fit their complex identities and aspirations and the politics of their place-making practices. It asks how Asian Americans made their home in Silicon Valley by reshaping and repurposing their given landscapes. What social and political conflicts have been fought over the physical changes that Asian American inspired? And how have these challenges affected the ways in which Asian Americans have been integrated into their communities and the benefits that suburbia once seemed to promise its residents?

Silicon Valley is a dynamic region that for nearly half a century has been at the cutting edge of technology as well as suburban change. In 2012, 18 of the 20 U.S. cities with the highest proportion of Asian American residents were suburbs. Among these, 7 were located in Silicon Valley—more than in any other region.8 Since the 1970s, Asian Americans have tended to concentrate in what geographer Wei Li popularly termed “ethnoburbs”—multiethnic, largely immigrant suburbs such as Monterey Park in southern California’s San Gabriel Valley.9 Many early ethnoburbs emerged near traditional immigrant gateway cities such as New York and Los Angeles.10 Increasingly, however, they can be found in places that have never before served as popular immigrant destinations: Research Triangle Park in North Carolina; Silicon Desert in Arizona; North Austin, Texas; Route 128 outside Boston; the Dulles and I-270 corridors outside Washington, D.C.; Route 1 in Middlesex County, New Jersey; and Silicon Valley.11

The common factor linking these regions is their thriving innovation economies. High-tech regions are diverse and fast-growing destinations for creative-class migrants and new immigrants, especially Asian Americans.12 As Wei Li and Edward Park point out, these “techno-ethnoburbs” are distinct from other centers of suburban immigration, including “LA-type ethnoburbs” such as Monterey Park, in terms of the populations they attract, their geographies, and their economic base.13 Through a deep investigation of Fremont, a suburb that is one of the most popular destinations for Asian Americans in Silicon Valley, this book highlights how high tech is shaping the dynamics of Asian American migration and community formation as well as the region’s landscape and often heated politics of social and spatial change.

Most scholarship on Asian Americans in Silicon Valley and other high-tech areas is concerned with their role in fueling the economy as scientists, engineers, researchers, and entrepreneurs or as low-wage, low-skilled laborers.14 Trespassers?, however, shows Asian Americans as community builders and place makers. It examines the ways in which Asian Americans in Fremont refashioned their surroundings to meet their desired lifestyles, paying particular attention to places through which they have marked and crafted their suburban sense of place.

Shut out of mainstream suburban social and economic life, Asian American migrants have long built “places of their own” in Silicon Valley suburbia.15 Particularly in the last few decades as Asian Americans and particularly Chinese and Indian immigrants have become a more significant presence in the region and wealthier than previous generations, they have transformed the spatial landscape of the valley in distinct ways. They moved into high-end neighborhoods to give their children the best education they could afford, shifting the social and academic culture of schools toward a more competitive environment with a more rigorous focus on math and science. In ethnic shopping centers, they established vibrant community spaces that service many suburbanites’ desires for Asian products and places that bridge the divide between their multiple geographies of home. And in several Silicon Valley neighborhoods, Asian Americans built homes that showcased their desires for modern spaces that fit their multigenerational households and aesthetic sensibilities.

These places mark a particular expression of the suburban American Dream for many Asian Americans in Silicon Valley. For generations of White Americans, white picket fences surrounding modest middle-class homes in racially homogeneous neighborhoods with good schools served as important markers of their success and prosperity. Among a generation of well-to-do, professional, and educated Asian Americans, however, their ability to move into racially diverse communities with high-performing schools, ethnic shopping centers, and large new homes are equally important markers of their achievements and desires.

Asian Americans’ efforts to weave their dreams within the valley’s existing spatial fabric have, however, been embattled. Over and over again, their efforts were met with skepticism, derision, and sometimes outright distain by established residents, city officials, planners, and others. Landscapes built by and for Asian Americans were portrayed as abnormal, undesirable, or simply “out of place.”16 The forms and uses of schools, shopping malls, and homes that Asian American newcomers inspired became markers of their seeming failure to integrate with and conform to their new environment. Further, these places, which I call landscapes of difference, became the focus of new city planning and design policies that tried to manage and mute their difference.

In the past, suburban inequality was marked and measured primarily by the exclusion of low-income residents, especially those of color, from suburbia’s borders. Today, however, inequalities exist among communities with far more diverse demographics and subtle expressions of social privilege and power. It is not only exclusionary attitudes that inhibit the ability of new suburbanites to carve out their own meaningful spaces. The dominant norms and standards that govern the landscape and limit expressions of difference in suburbia also reinforce White Americans’ privileged place within it. Together they comprise a normative framework in which certain spatial expressions are understood as acceptable, normal, or good, while others are not. Suburbia’s creed upholds spatial homogeneity, conformity, order, and stability as critical tenets of form. Though largely invisible, this framework has powerfully shaped suburban policy making and planning for decades, and its results are visible everywhere. Reinforced by local land-use policy, such ideas buttress the power of older suburbanites, principally the White middle class, to serve as the standard-bearers.

This book counters claims that boast of the postindustrial economy as color-blind and high-tech centers as postracial meritocracies. It also combats the proposition of Asian Americans as the so-called new Whites, whose high rates of homeownership, income levels, degree of educational attainment, and integration into White communities, particularly in the suburbs, suggest that they now enjoy the same privileges and benefits once reserved for White Americans.17 It is true that by all traditional measures, Asian Americans in Silicon Valley have, as a group, made it to the middle class. They are among the region’s most numerous and highly educated groups, have high incomes and high rates of homeownership, and are employed in large numbers in all ranks of high-tech employment. And yet, the landscapes they occupy, desire, and build are often read and regulated through the lens of racial and cultural difference. The constant challenges to their places of everyday life illustrate that not only class exclusion but also White cultural hegemony continue to push minorities to the suburban margins.

Importantly, Asian Americans in Silicon Valley have not been the passive recipients of such disregard. They have been highly vocal and politically active, commanding the attention of politicians, planners, and their neighbors. As Asian Americans cross the historically hardened boundaries of middle- and upper-class suburbs, they are no longer contesting exclusionary practices from the sidelines. They are fighting within suburbia for respect for the ways they use, occupy, and conceive of space and for a sense of place, belonging, and identity in their homes and communities. Their insurgent practices have claimed new spaces and challenged suburbia’s prevailing wisdom.18 They have drawn attention to Asian Americans’ values and aspirations as place makers and to their unique sense of being suburban. In doing so, they underscore how suburban landscapes, which have been designed as spaces of exclusion, can serve as touchstones for debate over what it means to be part of a more global, diverse, and inclusive society. Moreover, they bring to light how planning and policy making can foster more equitable metropolitan landscapes that provide their diverse occupants with the opportunity to carve out their own American Dream.

• • •

Scholars have long understood that landscapes are not simply vessels of the many meanings, values, and ideas of their users but are also shaped by them. Spaces become places when their inhabitants invest their memories, labors, and dreams in them. In doing so, people craft an ethic of care and attachment to the places of their everyday lives. Repeated over time and across generations, place meanings sediment themselves, becoming the scripts through which places are read and recognized from the outside as well as from within.

These scripts change as new groups arrive with their own ideas and patterns of work, home, and play. Time and time again in American cities, the process has repeated itself for waves of new immigrants. As groups settle in a neighborhood, they make their mark. They start language schools and cultural institutions that help bridge the gap between their new and old homelands, launch small businesses to gain a foothold in the American economy, and establish community spaces where they can share their hardships and triumphs with others like themselves. In this way, urban landscapes accumulate rich layers, comprising a bricolage of people, ideas, and meanings. They become mosaics of their storied pasts that exert a constant force in shaping their futures—prisms that can be read from different vantage points to tell multiple stories.

These processes are not just at work in the inner city. They have transformed the landscapes of communities across the United States. In suburbia, scholars have documented the community garden practices of early African American suburbanites, the fences and soccer fields that mark the barrio suburbanism of predominantly Mexican American neighborhoods outside Los Angeles, the temples and language schools of suburban Sahibs in New Jersey’s Middlesex County, and the garden apartments that served as social hotspots for seniors and young singles during the post-World War II period.19 Though often overlooked, suburbia has long served as a reflection of the diverse lifestyles of its residents.

Inherit within processes of place making is a politics of landscape change. As new groups come in and lay their ideas upon the landscape, they subtly challenge or subvert those of former groups. Their news signs and symbols assert a kind of moral authority that is often viewed as a threat by established residents, be they White, Black, poor, or middle class. These tensions raise questions of entitlement and belonging: For whom is this place being built? Who belongs here, and who does not? These are questions not just about values but also about power. Who gets to decide who stays, who goes, and who feels welcome? Visible markers of neighborhood change are contested in part because of the invisible power they hold to assert a collective sense of belonging or, alternatively, marginality. Whether dog parks, bike lanes, and coffee shops in San Francisco or ethnic shopping centers, Buddhist temples, and Chinese schools in Fremont, landscapes of difference are often the focal points of conflict over neighborhood change.20

The urban landscape in which these battles are meted out is not an even playing field. Certain groups have more power than others to transform landscapes in accordance with their values and interests and shape the ways in which these landscapes are read and valued, socially as well as economically. Scholars have long understood that urban space sustains social inequities. Seminal works by Henri Lefebvre, Michel Foucault, and David Harvey provide a prism for understanding how systems of inequality are reproduced in and through the built environment of cities—our streets, sidewalks, and office buildings.21 They show that the design, structure, and organization of urban places construct social identities and relationships of power, including those based on race and ethnicity.

Race is a social construction that requires the support of social, political, and economic institutions as well as spaces that mark social hierarchies and positionalities. As Michel Laguerre argues, “In order to have ethnic minorities, one must also have minoritized space.”22 Ghettos and barrios that were historically created by explicit policies of racial discrimination remain the subjects of uneven development and reinforce stereotypes about the incapacity or unwillingness of people of color to care for their communities and do what it takes to make it in America. In contrast, White neighborhoods, schools, and homes that have benefited from decades of discriminatory practices and policies are generally viewed as valued and valuable places that represent the fruits of White Americans’ hard work and ability. The racialized American landscape is all around us. As geographer Richard Schein notes, “all American landscapes are racialized, and can and should be seen through the lens of race.”23

For Asian Americans, the racialization of urban space was evident in the segregated Chinatowns, Japantowns, and Little Vietnams, whose borders were fiercely guarded by White vigilantes, urban planners, and city councils throughout much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet these same places came to serve as evidence of Asian Americans’ presumed inability to assimilate and their common depictions as “forever foreigners.” These neighborhoods often lacked public and private investment in housing, commercial businesses, schools, infrastructure, and social services. Yet their widespread portrayals as seedy, dark havens of criminal activity came to reflect on Asian Americans as the source of contagion, blight, and vice.24

In the mid-20th century, the racialization of Asian American space was evident in the devaluation of many ethnic enclaves during the urban renewal era that allowed city governments and private developers to raze and redevelop them for profit and the benefit of White suburbanites. Today, the racialization of space remains robust in stories told about these neighborhoods that erase the hardships and inequalities that have gone into their making while upholding them as evidence of the virtues of hard work and the success of the American multicultural experiment. At the same time, economic development schemes court tourists to neighborhoods that aestheticize and exotify Asian American culture and market it for profit.25 Discursively and materially, urban ethnic enclaves have helped to define Asianness in America.

The racialized landscape and its politics, however, does not respect city and suburban lines. Suburbia’s form has long been used to construct ideas about Whiteness and reinforce White Americans’ social and economic privilege and power.26 Postwar suburban housing, neighborhoods, streets, and shopping centers idealized the White middle-class nuclear family. Its picturesque and pastoral landscapes were modeled on the estates of the European elite and sold by developers and “community builders” as a new, exclusive version of the American Dream.27 Through practices such as racial steering, racially restrictive covenants, blockbusting, redlining, discriminatory Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration mortgage lending practices, and individual and collective acts of violence, this dream was denied to many lower-income residents, especially those of color.

As historians Becky Nicolaides and Andrew Wiese note, however, these spatial distinctions did not merely reify existing social hierarchies but also helped to shape ideas and understandings of them in ways that perpetuated them through time: “In building suburbia, Americans built inequality to last.”28 Contemporary suburban landscapes continue to naturalize ideas about who and what are rightly considered suburban. While all too often maintained by policies and practices such as common interest developments, gated communities, and exclusionary zoning that exclude poor and minority residents, suburban spaces often obscures the work that goes into maintaining their largely invisible though highly securitized borders as well as White Americans’ privileged position within them.29

If the scholarship is clear that suburbia has served and continues to serve as a landscape that constructs Whiteness and helps White Americans maintain their dominant social and economic status, however, it is less clear how this dynamic is changing in the face of more diverse inhabitants. We have come to a largely unanticipated moment when the majority of minorities and immigrants now live in the suburbs of America’s largest cities. Far more attention must be given to this side of the story. As several contemporary accounts of suburban minority and immigrant life have shown, neither discrimination against people of color nor the institutionalized barriers they face have been washed away by moving to the suburbs.30 For Asian Americans, several notable works have documented their battles over issues of political representation, language accommodation, cultural celebrations, religious facilities, and others in suburbia.31

Trespassers? demonstrates that built landscapes and spatial uses that do not conform to the suburban trope often become points of negotiation for the terms of Asian American suburban inclusion. In this process, policy and planning prescriptions commonly reinforce dominant spatial norms and standards of suburban design and development. The spaces occupied primarily by Asian Americans frequently fall outside these norms, creating a sense of Asian Americans as suburban trespassers—those who commit spatial acts that are not in accord with the dictates of the dominant rules. Governed by policies and processes that have long favored White Americans, suburbia’s built environment continues to racialize Asian American space and produce subtle modes of social and spatial marginality, even among minorities of means.

Alternatively, in investigating the resistance and persistence of landscapes of difference amid the pressures to conform or adapt to hegemonic ideas of suburban acceptability, this book also demonstrates that attempts to govern or legislate the terms of Asian American inclusion within suburbia has been incomplete. These spaces obstruct rather than reify the suburban spatial order and Asian Americans presumed place within it. They beg questions about what it means to be included and how to promote a sense of multiracial and multiethnic belonging, justice, and equity in a landscape built upon exclusion and inequality.32 This challenge requires looking at suburbia from the inside out. It demands an interrogation of the lived conditions and experiences of suburban newcomers and their struggles to build a sense of home and belonging. It also requires a recognition that simply living in suburbia or in diverse neighborhoods is not enough.33 The power to shape the built environment as a reflection of their diverse identities and desires is a condition of suburban citizenship that Asian Americans and other marginalized groups have long been denied.

• • •

If every place has a story, so too does every book. Mine began not in Silicon Valley but instead in the hollows of West Virginia. My African American mother and Chinese immigrant father raised me deep in the Appalachian foothills. This strange pair of hippie homesteaders were social idealists tethered to a set of principles about racial equity, citizen activism, democratic decision making, and environmental stewardship.34 Their vow to live principled, simplistic lifestyles led them and a few others to a small plot of land in my hometown, where they started a commune in the early 1970s. Like most, theirs did not last. Eventually the members dispersed into the backcountry of this rural region into which I was born.

As a product of this social experiment, my young life was governed by contradiction. I was raised to believe in social and racial equity, yet every day I felt the sting of discrimination and rural poverty around me. While I was taught to love and see my neighbors as equals, I was all too aware that many did not view me in the same light. My parents organized protests against the Ku Klux Klan, while some of our neighbors sat silently eyeing them with as much suspicion as the hooded shadows that paraded through my hometown.

Many of my summers were spent on the road with my father, who sold his handcrafted pottery at street fairs around the country. During these travels, I became fascinated by the possibilities of city life for fostering the kinds of communities that my parents had once imagined in which I might be raised—places not bound by color but held together by a commitment to diversity, democracy, and social justice. Here and there, I saw glimpses of the world my parents fought so hard for. In Chicago, New York, Ann Arbor, Minneapolis, and Cleveland, I was struck by how people of so many different colors and classes appeared to casually rub elbows on crowded urban streets. Eventually I also came to recognize the other side of this idyllic vision of city life—segregation, poverty, and the deep social inequalities that my parents had sought to escape.

These early experiences motivated my career as an urban planner and designer concerned with questions of urban social justice and inequality. As I learned about the forces that had shaped what Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton called “American Apartheid,” I became convinced that in the right hands, urban policy, planning, and design could remake American cities into the vibrant, diverse, and hopeful places that I had once imagined them to be.35

My studies led me to explore many intentionally diverse communities such as those in Columbia, Maryland, and Shaker Heights, Ohio, that were largely a product of my parents’ generation of progressive politics. But I found myself more concerned with the fundamental building blocks of cities—how the sidewalks, brick-and-mortar businesses, community centers, parks, and playgrounds supported diverse populations and improved people’s life circumstances. During my doctoral studies at the University of California, Berkeley, I began to look for clues about how urban form could better support diversity by exploring communities in my own backyard.

Armed with maps of the San Francisco Bay Area’s most ethnically diverse neighborhoods, I spent much of the summer of 2008 driving and walking through several low-income communities such as Pittsburg and Richmond as well as more middle-class communities such as Hercules, Vallejo, and Union City. To my surprise, my shoe-leather research brought me out of downtown Oakland and San Francisco into many low-density suburbs.

I was especially drawn to communities within Silicon Valley, where I sensed that there was something different happening. In contrast to the standard facades and manicured lawns I had seen in many suburbs, there I found custom-built homes, bustling ethnic businesses, and vibrant public spaces that appeared to be much richer expressions of difference. I wondered what had allowed these comparatively “messy” landscapes to emerge, how they supported the valley’s diverse populations, and what they suggested about the ways that different groups were and were not sharing space and building community together.

In search of answers to my many questions, I began spending more time there—primarily in Fremont, the largest Silicon Valley suburb by land area and one of the region’s most racially and ethnically diverse communities. On foot, by car, and lingering in many of Fremont’s public and semipublic spaces, I started to “take the city apart.”36 I explored its many neighborhoods and learned by seeing signs of difference in the landscape and asking questions about the people and processes that produced them.37 I sat down with business owners, residents, and city officials to hear their takes on the changing landscape I was witnessing firsthand. From old-timers, I heard what it was like to live through the valley’s swift transformation from a spattering of small rural townships into a global gateway. Many of their stories carried a deep unease about the changing demographics of the region and its impact on places that had once seemed so familiar and stable. Some complained about their new neighbors’ flashy oversized homes, Asian American parents pushing their kids too hard in schools, and the large number of new Asian-oriented shopping centers that were “taking over” the city. Asian Americans, especially recently arrived immigrants from China, Taiwan, and India, offered different perspectives. Their stories emphasized their struggles and successes in the valley. They spoke of the trials they underwent to establish themselves in the region and, with pride, at how far they had come. They showed off their large homes as signs of their success, boasted of their children’s high grade point averages, and frequently noted how much easier their lives had become because of the growing number of Asian American-owned businesses in the region. In city council and planning commission meetings, I listened as heated debates over these issues went back and forth between long-term and new residents.

These conflicts led to me to consider the spaces at the center of these debates and their importance to Asian American newcomers. As I dug deeper, I began conducting in-depth interviews with the people most familiar with these spaces and the social conflicts that surrounded them. I spoke with students, parents, principals, teachers, and school board members; the mayor, council members, planning commission members, planners, and other city staff; mall developers, store owners, and shoppers; homeowners, architects, and designers—over 130 in all. I spent time observing the everyday life of these spaces—hanging out in ethnic shopping malls, quietly sitting in the back of high school classes, and wandering the streets of neighborhoods most affected by large home development. I tracked census figures and demographic and spatial data available from government offices; spent days engulfed in the archives of the city council, the school board, the planning department, and local libraries; and became an avid reader of local and regional news, both past and present.38

My research helped me to resolve my initial reluctance to write about Asian Americans in Silicon Valley from the perspective of some of the most economically privileged among them. I worried that focusing primarily on the stories of Chinese and Indian Americans, Fremont’s largest Asian American groups, many of whom were highly educated, high-income professionals, would ignore the struggles of many who could not even afford entry into the valley’s exclusive suburbs. Indeed, the class status of many of Fremont’s Asian American residents has reinforced their efforts to carve out a place for themselves within this privileged suburb and many high-end neighborhoods within it. Further, their racialization as model minorities has led to their perceived exceptionalism compared with other groups that has further aided their integration and acceptance within White suburban communities.39 Yet I also began to see that the desires of high-income professional Asian Americans to reshape their communities according to their own values were shared by many. Rich and poor, White and non-White, single parents, lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people, teens, multigenerational households and other residents whose preferences do not conform to established suburban norms all struggle in various ways with a landscape that was simply not built with them in mind.40

• • •

Landscapes offer a way to tell stories about a place.41 This book is organized around landscapes that recount Asian Americans’ struggles to make their homes in Silicon Valley. Collectively, these places and their politics show a suburban region turned upside down by battles over growth and development during a period of rapid immigration and demographic change.

The book begins by tracing the forces that drove Asian Americans’ multiple migrations to Silicon Valley. Chapter 1, “The New Gold Mountain,” explores why the valley became such an important hub of racial and ethnic diversity, especially among recently arrived Asian immigrants in the latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century. Beginning with a brief look back at the pathways forged by early Asian American pioneers, the chapter focuses on the sweeping changes that occurred in the region economically, spatially, and socially after World War II. This period was defined by the region’s transformation from a largely rural economy to one driven by technological innovation and its simultaneous conversion from an agricultural landscape to one dominated by white-collar office parks and exclusive middle-class neighborhoods. After 1965, the valley’s boom in high tech began to reshape the demographics of the region as successive waves of immigrants, particularly those from Asia, began arriving to fill both highly skilled and unskilled jobs in the region’s burgeoning technology industries. The chapter shows how Asian Americans navigated their new terrain and put down roots in working- and middle-class neighborhoods. Some suburbs, such as Fremont, became particularly popular among middle-class Chinese and Indian Americans who made up the majority of the region’s newcomers. Local factors such as good schools, new and relatively affordable homes, easy access to high-tech jobs, and an extant Asian American community contributed to Fremont’s role as a popular meeting ground for Asian American migrants. The chapter underscores how this suburb’s rapid growth and development were prefaced on the valley’s booming innovation economy and Asian Americans’ own suburban dreams.

The next three chapters focus on the ways in which Asian Americans reshaped the region’s built form, social geography, and development politics. Chapter 2, “A Quality Education for Whom?,” considers how migrants’ educational priorities and practices reshaped Silicon Valley neighborhoods and schools. For many Asian American families, high-performing schools have been among the most important factors drawing them to particular communities around the region and to their imagined geography of “good” suburban neighborhoods. The academic culture and practices that Asian Americans introduced in Fremont schools, however, has been met with considerable resistance. A case study of the Mission San Jose neighborhood in Fremont shows that as large numbers of Asian American families moved into the community, primarily for access to its highly ranked schools, many established White families moved out. This pattern of so-called White flight was driven in part by tensions between Asian American and White students and parents over educational values, school culture, and academic competition. Although Asian Americans’ new wealth bought them entrée into some of the region’s best schools, their educational practices were widely criticized. Intense citywide battles erupted over school culture and curricula as parents and students asked whose values they represented and who they benefited most.

Chapter 3, “Mainstreaming the Asian Mall,” investigates Asian American-oriented shopping centers that are an increasingly popular part of the Silicon Valley landscape. The chapter shows that these malls are central in the lives of Asian American suburbanites. For many, the malls serve their practical needs, support vital social networks, and foster their sense of place, community, and connection to the larger Asian diaspora. But these vibrant pseudopublic spaces are also deeply contested. In Fremont, many non-Asian American residents, policy makers, and planners have charged that these malls are socially exclusionary and questioned their deviance in form and norm from the conventions of suburban retail. The chapter shows how these debates have framed ethnic shopping malls as “problem spaces” that required greater regulation and scrutiny. Yet planners and city officials have also used their power to regulate and control these shopping centers to promote particular visions of multiculturalism that are more aligned with their projected image of a middle-class suburb.

Chapter 4, “That ‘Monster House’ Is My Home,” examines controversies over the building of large homes, or what some derisively call “McMansions” or “monster homes,” in established neighborhoods. Fremont’s large home debates reveal the different norms and values for single-family suburban homes and neighborhoods held by many Asian American and White residents in Silicon Valley. The chapter shows that the planning processes, development standards, and design guidelines adopted to deal with these conflicts largely reflected the interests of established White residents while marginalizing those expressed by Asian Americans. The debate highlights how planning processes and seeming neutral regulations often employ dominant social and cultural norms about “good” and “appropriate” design that reinforce suburbia’s established racial and class order.

Finally, Chapter 5, “Charting New Suburban Storylines,” examines the lessons from this exploration of social and spatial change in Silicon Valley for suburban development, design, and community building. This case study challenges communities to examine the ways in which they are making space for minorities, immigrants, and other suburban newcomers. In an era characterized by global metropolitan diversity, the conditions that gave rise to development contests in Fremont are not unique. To welcome new suburban migrants, communities must wrestle with the standards and tools of regulation that govern their landscapes. They must shift their spatial norms from those that celebrate conformity, consensus, and stability to those that respect difference, contestation, and change. If the 21st-century migrant metropolis is to become more sustainable and more just, these principles must be central to efforts to regenerate and redesign suburbia.42

Suburbia is clearly not what it used to be. Scholars, residents, planners, and policy makers, however, have yet to develop shared vocabularies to describe what it is or is becoming. As Xavier de Sousa Briggs pointed out, suburbia offers an opportunity to think about old urban issues in new ways.43 It is my hope that within these pages, readers will discover fresh ways of thinking about the challenges of inequality and social justice in the contemporary metropolis and new possibilities for improving our collective capacity to live at home together.