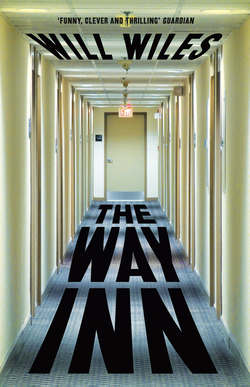

Читать книгу The Way Inn - Will Wiles - Страница 8

ОглавлениеThe bright red numbers on the radio-alarm clock beside my bed arranged themselves into the unfortunate shape of 6:12. Barely four hours since I went to sleep, I was abruptly awake. I remembered that I had been in the bar, and that I had seen the woman again.

Apart from the red digital display – 6:13 – the room was dark. And the preceding day was clear: I had seen her again, and I had spoken to her. Over the years I had come to believe that my memory was steadily enhancing this woman. Our first encounter was so out of the ordinary that it took on a completely unreal complexion in retrospect, and I suspected that I might be elaborating on it, on her, to make the whole bizarre incident more exotic. But there she was again, matching perfectly what I had assumed was an idealised vision. Her Amazonian height, and her pale skin and red hair – even in the flesh, there was something about her that didn’t quite match up to reality, as if she was too high definition. Just hours later our reunion had already taken on the qualities of a dream. One that had been interrupted before it was complete. Maurice. Maurice had ruined it.

A return to sleep seemed unlikely and unwise. It was less than an hour until the alarm would go off and I had no intention of oversleeping and being forced to head to the fair without a shower and breakfast.

The hotel room was well heated, the carpet soft and warm under my feet. It was quiet, almost silent, but the air conditioner hummed its low hum, and there was something else in the air – a kind of electromagnetic potential, a distorted echo beyond the audible range. Or nothing, just the membranes of the ear settling after being startled from sleep. Outside it would be cold. I opened the curtains but could see little. The sullen orange glow of the motorway to one side, an occluded sky untouched by dawn, and on the level of the horizon a shivering cluster of red lights that suggested, somehow, an oil refinery. Maybe the airport – radar towers, UHF antennae.

I switched on the room lights. Latte-coloured carpet, a cuboid black armchair, a desk with steel and wicker chair, a flat-screen TV on the wall and of course an insipid abstract painting. It was like every other hotel room I’ve stayed in: bland, familiar, noncommittal, unaligned to any style or culture. I once read that the colour schemes in large chain hotels were selected for how they looked under artificial light, on the understanding that the business people staying in the rooms would mostly be there outside daylight hours. And that principle must also apply to the art on the walls – and again I remembered the woman in the bar, what she had said about the paintings. The indistinct background hum seemed a little louder – it had to be the air-con, or the minibar under the desk. It was a benign sound, almost soothing, a suggestion that I was surrounded by advanced systems dedicated to keeping me comfortable.

Showering took the edge off my tiredness, and allowed me to ignore it. I put on a Way Inn bathrobe and returned to the bedroom, drying my hair with a Way Inn towel. The TV was on, but only showed the hotel screen that had greeted me on my arrival in the room last night.

WELCOME MR DOUBLE

Above this was the corporate logo, a stylised W in the official red. A stock photo of a group of Way Inn staff, or models playing Way Inn staff, smiled up at me. Room service numbers and pay-TV options were listed underneath. Today’s special in the restaurant was pan-seared salmon. The weather for today and tomorrow: fog and rain. Temperature scarce degrees above zero. I picked up the remote and found the BBC News.

The sky had lightened, but the view had not improved. The glass in the window was thick, presumably soundproofed against the nearby airport, and it gave the landscape a sea-green tint. Mucoid mist shrouded nearly everything. My room was on the second floor of the hotel. Outside was a strip of car park bounded by a chain-link fence, then an empty plot on which a few stacks of orange traffic barriers and half a dozen white vans were slowly sinking into mud. To the extreme right there was a road flanked by a long artificial ridge of earth scabbed with weeds, over which the streetlights of the motorway could be seen. The lights could also be seen reflected in the water-filled ruts that vehicles had left in the scraped-back land; under the mud everything waited to be made over again, more streetlights, more car parking, more windows to look out of.

Many people, I imagine, would find this a depressing scene. But not me. I love to wake in a hotel room. The anonymity, the fact the room could be anywhere – the features that fill others with gloom fill me with pleasure. I have loved hotels since the first time I set foot in one.

I dressed, half-listening to headlines coming from the TV. It was nothing, everything, all things I knew, had heard before. Events. People crushed against a wall, wailing women somewhere hot, an American ambulance boxy orange and white in that too-bright American style of TV footage, then more familiar video-texture from the UK, flowers zip-tied to a signpost beside a road, tears in camera flashes, an appeal for witnesses. The newsreader looked up from her screen and seemed, for a split second, to be surprised by the sight of cameras. World weather. A list of major cities with numbers beside them, little icons meaning sunshine and storms, a world reduced to a spreadsheet of data points. I flipped open my laptop and it came to life. Heavy black unread emails were heaped in my inbox. Invitations, press releases, mailing lists, flight and hotel bookings. More headlines refreshing in my readers. For a moment I was aware of everything, everything was in reach, and then the wifi symbol flashed and stuttered. A bubble warned me that my connection was lost, and I snapped my laptop shut. The TV was still on – a palm tree jerked and writhed, thrashing back and forth as debris passed it horizontally and the camera went dead. Unseasonal. The newsreader looked up, saw me, and told me the number of dead. I plucked my keycard from its plastic niche on the wall, killing the room.

Myself, reflected to infinity, bending away into an unseeable grey nothing on a twisted horizon.

The lift came to a smooth halt. My myriad reflections in its mirrored walls stopped looking at each other. The doors opened, revealing the bright lobby and a pot-bellied man with a moustache, who stared back at me as if astonished that I should be using his lift.

‘Sorry,’ I mumbled, a social reflex, and stepped out.

Music had been playing in the lift, softly, as if it was not meant to be heard. If it was not meant to be heard, why play it at all? To prevent silence, perhaps, to insulate the traveller from isolation and reflection, just as the opposing mirrors provided an unending army of companions that was best admired alone. But I had heard the music, and had been trying to identify it. The answer had come when the doors opened: ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’, instrumental, in a zero-cal easy-listening style.

Wet polymers hung in the air. The hotel was new, new, new, and the chemicals used to treat the upholstery and carpets perfumed the lobby. Box-fresh surfaces blazed under scores of LED bulbs. The lobby was a long, corridor-like space connecting the main entrance with one of the building’s courtyards. These courtyards were made up to look like Japanese Zen meditation gardens, a hollow square of benches enclosing an expanse of raked gravel, a dull little pond and a couple of artfully placed boulders, slate-slippery with rain. I have stayed in twenty or thirty Way Inn hotels and I have never seen anyone use those spaces to meditate. They use them to smoke. But that’s hotels, really – everything is designed for someone else. Meditation gardens you don’t meditate in, chairs you don’t sit in, drawers you don’t fill containing Bibles you don’t read. And I don’t know who’s using those shoe-cleaning machines.

Opposite the reception desk a line of trestle tables had been set up in the night, and were now staffed by public-relations blondes. Business-suited people and mild conversation filled the space between the PRs and the hotel staff, checking in, carrying bags in and out, picking up papers, shaking hands. Beyond a glazed wall, the restaurant was busy. A banner over the trestles read YOU CAN REGISTER HERE.

Very well then. I walked over; confident, unrecognised, at home. These moments, the first contact between myself and the target event, I treasure. They do not yet know who I am, what my role or meaning might be. But I know everything about them.

A blonde woman smiled at me from the other side of the table, over a laptop computer and a spread of hundreds of identical folders. ‘Good morning,’ I said, holding out a business card. ‘Neil Double.’

She took the card, studied it momentarily, and tapped at the keyboard of the laptop. Although I couldn’t see her screen, I knew exactly what she was looking at – my photograph, the personal details that had been fed into the ‘*required’ boxes of an online form six months ago, little else. ‘Mr Double,’ she said, English tinged with a Spanish accent, her smile a few calories warmer than before. ‘Welcome to Meetex.’

A tongue of white card spooled out of the printer connected to the woman’s laptop. In a practised, brisk move, she tore it off, slipped it into a clear plastic holder attached to a lanyard and handed it to me. ‘You’ll need this to get in and out of the centre,’ she said. I nodded, trying to convey the sense that I had done this before, that I had done it dozens of times this year alone, without being rude. But she pressed on, perhaps unable to change course, conditioned by repetition into reciting the script set for her, as powerless as the neat little printer in front of her. ‘Sure, sure,’ I said. Panic flickered in her eyes. ‘Just hang it around your neck – if you want to give your details to an exhibitor, they can scan the code here.’ A blocky QR code was printed next to my name and that of my deliciously inscrutable employer: NEIL DOUBLE. CONVEX.

‘Right,’ I said.

‘You can just hang it around your neck,’ she repeated, indicating the lanyard as if I might have missed it. In fact it was hard to ignore: a repellent egg-yolk yellow ribbon with the name of the conference centre stitched into it over and over. METACENTRE METACENTRE METACENTRE.

‘Right,’ I said, stuffing the pass into my jacket pocket.

‘Buses leave every ten or fifteen minutes. They stop right outside. And here’s your welcome pack.’ She handed me one of the folders, smiling like an LED.

I smiled back. ‘Thanks so much,’ I said. And I was fairly sincere about it. It’s a good idea to stay friendly with the staff at these conferences; I doubted I would see her again, but it was better to be on the safe side. Generally it was a waste of time trying to sleep with them, though – they often couldn’t leave their post, and they were kept busy. She had already moved on from me, directing her smile over my shoulder to whoever stood behind me. I saw that she had access to scores of disgusting emergency-services-yellow tote bags from a box beside her, but she had not offered one to me. A shrewd move on her part; I was pleased by her reading of my level of MetaCentre-tote-desire, which was clearly broadcasting at just the right pitch.

Breakfast was served in the restaurant, separated from the lobby by a sliding glazed wall. Flexible space, ready for expansion or division into a large number of different configurations. A long buffet table was loaded with pastries, bread, sliced fruit and cereals. Shiny steel containers sweated like steam-age robot wombs. Flat-screen TVs with the news on mute, subtitles appearing word by word. Current affairs karaoke. I poured coffee into an ungenerous cup from a pot warming next to jugs of orange, grapefruit and tomato juice, and put an apricot Danish and a fistful of sugar sachets on a plate. Then I started my hunt for somewhere to sit. Perhaps half of the seats were taken – lively conversation surrounded me. When a hotel is filled with people all attending the same conference, breakfast can present all sorts of diplomatic hurdles. I am rarely gregarious, and at breakfast time I am at my least social, always preferring to sit alone. This was in no way unusual – the hubbub disguised the fact that many of the diners here were alone, studying phones or newspapers or laptops. The first morning of an event can be the least social, before people fall into two-day friendships and ad hoc social bubbles. But I still had to be careful not to blank anyone who had come to recognise me. At other conferences, I might run into the same people once or twice a year. This one was different. These people I see all the time, everywhere; I am getting to know some of them; far worse, they are getting to know me. My detachment is a crucial part of what I do – these people don’t understand that. They love to think of themselves as a ‘community’; they thrive on ‘relationships’. No ‘community’ includes me. But try telling them that. Or rather, don’t try. Try telling them nothing. Adam had been most specific: keep a low profile.

But as I scanned the room looking for the right spot I realised, with a twinge of embarrassment, that I was not only looking out for people to politely evade – I was also trying to find the red-haired woman. But without luck. She was not in the restaurant.

A good spot presented itself. It was in a rank of small tables connected by a long banquette upholstered in white leather – a flexible seating arrangement, designed to suit both groups and lone diners. Two people I recognised were already sitting at one of the tables, and the chemistry of our acquaintance had about the right pH level. Phil’s company built the scanners that read bar codes and QR codes. We had talked at length before – it helps me to understand that sort of technology. His companion I knew less well – her name was Rosa or Rhoda, perhaps Rhonda, and she worked for a databasing service. I nodded to them as I sat, an acknowledgement carefully poised between amity and reserve. Let them make the first move. They smiled back, and their low-tempo conversation resumed. Were they sleeping together? Phil was at least fifteen years Rosa/Rhoda’s senior, and the ring finger of his left hand had shaped itself to his wedding band, but that meant almost nothing. Industry conventions dissolved other conventions. These events were often the Mardi Gras of their fiscal years: intervals of misrule, free zones where the usual professional and social boundaries were made fluid. At their worst they resembled the procreative frenzies of repressed aquatic creatures blessed with only one burst of heat per lifetime, seething with promiscuity and pursuit. And then, bleary-eyed, the attendees sat quietly on their planes and trains home, and opened their wallets not to buy more drinks, order oysters on room service or pay for another private dance, but to turn around the photos of their kids so they once again face outwards. What happened in Vegas, Milan, Shanghai, Luton, stayed there; it stayed where they had stayed, in Way Inn, Holiday Inn, Ibis, Sofitel, Hilton, where non-judgemental, faceless workers changed their sheets. But the body language between Phil and his companion didn’t support my hypothesis. Pretending to read the information pack I had been given, I watched them – I am of course adept at observing unobserved. There was no surreptitious touching, no encrypted smiles. They had the easy manner of friends, but they were talking business – data capture, facial recognition, RFID, retrieval technologies. Little of what they said conflicted with what I knew already.

Since I was staring at the conference programme, pretending to read it, I decided that I could divert some attention its way and give some thought to the day ahead. A couple of sessions on the timetable had been flagged up by my clients as mandatory – routine fare such as ‘The Austerity Conference’ and ‘Emerging Threats to the Meetings Industry’ – but it was always good to attend a few extra to get a rounded view of an event. No one expected a comprehensive report from every session – there were three halls of different sizes at the MetaCentre, with talks going on simultaneously in each, and further fringe events in function rooms in the hotels. All I needed was a sample. ‘Trap or Treat: Venue Contract Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them’. To avoid, I think. ‘China in Your Hands: Event Management in the Far East.’ That could be worth attending. By which, I don’t mean I expected to find it interesting – or that I did not. The things that interest me are not necessarily the things that will interest my clients. And these trade fair conferences are nearly always very boring. If they were not, I wouldn’t have a job. The boring-ness is what fascinates me. I soak it up: boring hotels, boring breakfasts, boring people, boring fucks, boring fairs, the boring seminars and roundtables and product demos and presentations and launches and plenary sessions and Pecha Kuchas, and then I … report. These people, the people sitting around me, the people whose work involves organising and planning the conferences I spend my life attending: if they knew what I was doing, and how I felt about what they did, they might not be pleased.

A tuft of polythene sprouted from a joint on the underside of my table. It had only just been unwrapped. That chemical smell rose from the white leather of the banquette, adulterated but not hidden by the breakfast aromas. Was it real leather or fake leather? Its softness under the fingertips, its over-generous tactility, felt fake, designed to approximate the better qualities of leather rather than actually possessing them, but I had no way of telling for sure. New leather, certainly. Everything new for a new hotel. Scores of identical chairs and tables. Multiplied across scores of identical hotels. It’s big business, making all those chairs and tables, ‘contract furniture’ they call it, carpet bought and sold by the square mile – and I attended those trade fairs and conferences too. If the leather was real, equipping all the hundreds of Way Inn hotels would mean bovine megadeath. But I remembered what the woman had said about the paintings in the bar, and thought instead of a single vast hide from a single unending animal …

That was why she was in the bar: she had been photographing the paintings. It was late, past midnight already, and I wanted a quick nightcap before going to my room. One of the night staff served me my whisky and returned to the lobby, where he chatted quietly with a colleague at the reception desk. I had registered that I was not alone in the darkened bar, but no more than that. What made me look up was the flash of her camera. I kept looking because I knew at once that I had seen her before – and, too exhausted for subtlety, I let the meter run out on my chance to gaze undetected, and she raised her head from her camera’s LCD display and saw me.

We had met before, I said – not met, exactly, but I had seen her before. She remembered the incident. How could she forget something like that? Naturally, as a mere spectator, I was not part of her memory of what had happened; I was just one of the background people. Her explanation of how she came to be there, in that state, made immediate, obvious sense, but left me embarrassed. To close the horrible chasm that had opened in the conversation, I asked why she was photographing the paintings.

A hobby, she said. The paintings were all over the hotel – in my room, here in the restaurant, out in the lobby, in the bar. And so it was in every Way Inn. They were all variations on an abstract theme: meshing coffee-coloured curves and bulging shapes, spheres within spheres, arcs, tangents, all inscrutable, suggestive of nothing. I had never really examined them – they were not there for admiring, they were there simply to occupy space without distracting or upsetting. They were an approximation of what a painting might look like, a stand-in for actual art. They worked best if they decorated without being noticed. All they had to do was show that someone had thought about the walls so that you, the guest, didn’t have to. An invitation not to be bothered. Now that she had drawn my attention to them, I could see that she was right – they were everywhere. How many in total? I felt uncomfortable even asking.

‘Thousands,’ she had said, as if sharing a delicious secret. ‘Tens of thousands. More. Way Inn has more than five hundred locations worldwide. They never have fewer than one hundred rooms. Each room has at least one painting. Add communal spaces. Bars, restaurants, fitness centres, business suites, conference rooms, and of course the corridors … At least a hundred thousand paintings. I believe more.’

I could see why this was a calculation she delighted in sharing with people – the implications of it were extraordinary. Where did all the paintings come from? Who was painting them? With chairs, tables, carpets, light fixtures, there were factories – big business. But works of art? They weren’t prints; you could see the brush marks in the paint. It was thoroughly beyond a single artist.

‘There is no painter,’ she said. ‘No one painter, anyway. It’s an industrial process. There’s a single vast canvas rolling out into a production line. Then it’s cut up into pieces and framed.’

As she said this, she showed me the other photos on her camera, the blip-blip-blip of her progress through the memory card keeping time in her conversation. She was tall, taller than my six foot, and leaned over me as she did this, red hair falling towards me – a curiously intimate stance. The paintings flicked past on the little screen, bright in the gloom. The same neutral tones. The same bland curves and formations. Sepia psychedelia. A giant painting rolling off the production line like a slab of pastry, ready to be stamped into neat rectangles and framed and hung on the wall of a chain hotel … there was something squalid about it.

‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Why collect something that’s made like that? What’s so interesting about them?’

‘Nothing, individually, nothing at all,’ she said. ‘You have to see the bigger picture.’

‘Late night?’

A second passed before I realised that I had been addressed, by Phil. His conversation with Rosa (or Rhoda) had lapsed. She prodded at her phone. Not really reading, not really listening, I had slipped into standby mode and was staring into space.

I made an effort to brighten. ‘Quite late,’ I said. ‘I got here at midnight.’ And then I had talked to the woman – for how long? – until Maurice detained me even later. Hotel bars, windowless and with only a short walk to your bed, made it easy to lose track of time.

‘I got here yesterday morning,’ Phil said. ‘We’re exhibiting, so there was the usual last-minute panic … got to bed late myself. Slept well, though. Did you get a good room?’

‘Yes,’ I said. In truth I was indifferent to it, precisely as the anonymous designers had intended. Indifferent was good. ‘It’s a new hotel.’ The same faces, the same conversations. People like Phil – inoffensive, with few distinguishing characteristics and a name resonant with normality. The perfect name, in fact. Phil in the blanks. Once I put it to a Phil – not this Phil – that he had a default name, the name a child is left with after all the other names have been given out. He didn’t take it well and retorted that the same could be said of my name, Neil. There was some truth to that.

Phil rolled his eyes. ‘Too new. Like one of those holiday-from-hell stories where the en suite is missing a wall and the fitness centre is full of cement mixers.’

The hotel looked fine to me – obviously new, but running smoothly, as if it had been open for months or years. ‘There’s a fitness centre?’

‘No, no,’ Phil said. He stabbed a snot-green cube of melon with his fork, then thought better of it and left it on his plate. ‘I don’t know. I’m talking about the Skywalk. The hotel is finished, the conference centre is finished, but the damn footbridge that’s meant to link them together isn’t done yet. So you have to take a bus to get to the fair.’ The melon was lofted once more, and this time completed its journey into Phil. He gave me a disappointed look as he chewed.

‘I don’t understand,’ I said, patting the information pack in front of me, a pack that contained a map of the conference facilities, lined up next to each other as neat as icons on a computer desktop. ‘The conference centre is two minutes away, but you have to take a bus?’

‘There’s a bloody great motorway in the way,’ Phil said. ‘No way around it but to drive. We spent half of yesterday in a bus or waiting for a bus.’

‘What a bore,’ I said. So it was; I was ready to bask in it. It’s part of the texture of an event, and if it gets too much there is always something to distract me. In this case it was Rhoda, Rosa, whatever her name was, still plucking and probing at her phone, although with visibly waning enthusiasm, like a bird of prey becoming disenchanted with a rodent’s corpse. Cropped hair, cute upturned nose – she was divertingly pretty and I remembered enjoying her company on previous occasions. If there was queuing and sitting in buses to be done, I would try to be near her while I was doing it. Sensing my attention, she looked up from her phone and smiled, a little warily.

Behind Rosa, a familiar figure was lurching towards the cereals. Maurice. It was a marvel he was up at all. The back of his beige jacket was a geological map of wrinkles from the hem to the armpits. Those were the same clothes he had been wearing last night, I realised in a moment of terror. I issued a silent prayer: please let him have showered. But maybe he wouldn’t come over, maybe he would adhere to someone else today. He picked up a pastry, sniffed it and returned it to the pile. A cup of coffee and a plate were clasped together in his left hand, both tilting horribly. My appalled gaze drew the attention of Rosa, who turned to see what I was looking at – and at that moment Maurice raised his eyes from the buffet and saw us. We must have appeared welcoming. He whirled in the direction of our table like a gyre of litter propelled by a breeze. Despite his – our – late night, he glistened with energy, bonhomie, and sweat.

It pains me to admit it, but Maurice and I are in the same field. What we do is not similar. We are not similar. We simply inhabit the same ecosystem, in the way that a submarine containing Jacques Cousteau inhabits the same ecosystem as a sea slug. Maurice was a reporter for a trade magazine covering the conference industry, so I was forever finding myself sharing exhibition halls, lecture theatres, hotels, bars, restaurants, buses, trains and airports with him. And across this varied terrain, he was a continual, certain shambles, getting drunk, losing bags, forgetting passports, snoring on trains. But because we so often found ourselves proximal, Maurice had developed the impression that he and I were friends. He was monstrously mistaken on this point.

‘Morning, morning all,’ he said to us, setting his coffee and Danish-heaped plate on the table and sitting down opposite me. I smiled at him; whatever my private feelings about Maurice, however devoutly I might wish that he leave me alone, I had no desire to be openly hostile to him. He was an irritant, for sure, but no threat.

‘Glad to see you down here, old man,’ Maurice said to me, not allowing the outward flow of words to impede the inward flow of coffee and pastry. Crumbs flew. ‘I was concerned about you when we parted. You disappeared to bed double quick. I thought you might pass in the night.’

‘I was very tired,’ I said, plainly.

‘Or,’ Maurice said, leaning deep into my precious bubble of personal space, ‘maybe you were in a hurry to find that girl’s room!’ He started to laugh at his own joke, a phlegmy smoker’s laugh.

‘No, no,’ I said. I am not good at banter. What is the origin of the ability to participate in and enjoy this essentially meaningless wrestle-talk? No doubt it was incubated by attentive fathering and close-knit workplaces, and I had little experience of either of those. At the conferences, I was forever seeing reunions of men – co-professionals, opposite numbers, former colleagues – who had not seen each other in months or years, and the small festivals of rib-prodding, back-slapping, insult and innuendo that ensued.

‘What’s this?’ Phil asked, clearly amused at my discomfort. Rosa/Rhoda’s expression was harder to read; mild offence? Social awkwardness? Disappointment, or even sexual jealousy? I hoped the latter, pleased by the possibility alone.

‘Neil made a friend last night,’ Maurice said. ‘I found him trying it on with this girl …’ he paused, eyes closed, hands raised, before turning to Rosa: ‘… excuse me, this woman … in the bar.’

‘Jesus, Maurice,’ I said, and then turning to Rosa and Phil: ‘I ran into someone I know last night and was chatting with her when Maurice showed up. Obviously, at the sight of him, she excused herself and went to bed.’

Maurice chuckled. ‘I don’t know. You looked pretty smitten. Didn’t mean to cock-block you.’

‘Jesus, Maurice.’

‘You’re a dark horse, Neil,’ Phil said.

‘Just a friend,’ I said, directing this remark mostly at Rosa/Rhoda.

‘Of course, of course,’ she said. Then she stood, holding up her phone like a get-out-of-conversation-free card. ‘Excuse me.’

‘So, what’s her name, then?’ Maurice asked. ‘Your friend.’

A sickening sense of disconnection rose in my throat. I didn’t know her name. Against astonishing odds I had re-encountered the one truly memorable stranger from the millions who pass through my sphere, and I had failed to ask her name or properly introduce myself. I had kept the contact temporary, disposable, when I could have done something to make it permanent. Maurice’s arrival in the bar had broken the spell between us, the momentary intimacy generated by the coincidence, before I had been able to capitalise on it. And now I was failing to answer Maurice’s question. He surely saw my hesitation and sense the blankness behind it.

‘Because you could ask the organisers, leave a message for her. They might be able to find her.’

‘She’s not here for the conference,’ I said, relieved that I could deviate from this line of questioning without lying.

‘Not here for the conference?’ Maurice said, now blinking exaggeratedly, pantomiming his surprise in case anyone missed it. All of Maurice’s expressions were exaggerated for dramatic effect. When not hamming it up, in moments he believed himself unobserved, his expression was one of innocent, neutral dimwittedness. ‘She must be the only person in this hotel who isn’t! Good God, what else is there to do out here?’

‘She works for Way Inn.’

‘Oh, right, chambermaid?’ Maurice said, and Phil barked a laugh.

I smiled tolerantly. ‘She finds sites for new hotels – so I suppose she’s checking out her handiwork.’

‘So she’s to blame,’ Phil said. ‘Does she always opt for the middle of nowhere?’

‘I think the conference centre and the airport had a lot to do with it.’

‘Aha, yes,’ Maurice said. Without warning, he lunged under the table and began to root about in his satchel. Then he re-emerged, holding a creased magazine folded open to a page marked with a sticky note. The magazine was Summit, Maurice’s employer, and the article was by him, about the MetaCentre. The headline was ANOTHER FINE MESSE.

‘I came here while they were building it,’ Maurice said. He prodded the picture, an aerial view of the centre, a white diamond surrounded by brown earth and the yellow lice of construction vehicles. ‘Hard-hat tour. It’s huge. Big on the outside, bigger on the inside: 115,000 square metres of enclosed space, 15,000 more than the ExCel Centre. Thousands of jobs, and a catalyst for thousands more. Regeneration, you know. Economic development.’

I heard her voice: enterprise zone, growth corridor, opportunity gateway. That lulling rhythm. I wanted to be back in my room.

‘Did you stay here?’ Phil asked.

‘Nah, flew in, flew out,’ Maurice said. ‘This place is brand new. Opened a week or two ago, for this conference I’m told.’

‘So they say,’ I said, just to make conversation, since there appeared to be no escaping it for the time being. To make conversation, to keep the bland social product rolling off the line, word shapes in place of meaning. While Phil again explained the unfinished state of the pedestrian bridge and our tragic reliance on buses, I focused on demolishing my breakfast. Maurice took the news about the buses quite well – an impressive performance of huffing and eye-rolling that did not appear to lead to any lasting grievance. ‘The thing is,’ he said, as if communicating some cosmic truth, ‘where there’s buses, there’s hanging around.’

There was no need for me to hang around. My coffee was finished, my debt to civility paid.

‘Excuse me,’ I said, and left the table.

Back in my room, housekeeping had not yet called, and the risen sun was doing little to cut through the atmospheric murk beyond the tinted windows. The unmade bed, the inert black slab of the television, the armchair with a shirt draped over it – these shapes seemed little more than sketched in the feeble light. Before dropping my keycard into the little wall-mounted slot, which would activate the lights and the rest of the room’s electronic comforts, I walked over to the window to look out. It wasn’t even possible to tell where the sun was. Shadowless damp sapped the colour from the near and obliterated the distant. The thick glass did nothing to help; instead it gave me a frisson of claustrophobia, of being sealed in. I looked at its frame, at all the complicated interlayers and the seals and spacers holding the thick panes in place: high-performance glass, insulating against sound and temperature, allowing the hotel to set its own perfect microclimate in each room.

A last look as I recrossed the small space – the brightest point in the room was the red digital display of the radio-alarm on the bedside table. I slid the card in the slot and the room came alive. Bulbs in clever recesses and behind earth-tone shades. Stock tickers streamed across the TV screen. In the bathroom, the ascending whirr of a fan. I brushed my teeth, stepping away from the sink to look at the painting over the desk, the only example of the hotel’s factory-made art in my room. The paintings in the bar had seemed so threatening last night – remembering the moment, the threat had come not from what lay within their frames but from the possibility of what lay outside them.

You have to look at the bigger picture, she said – and she meant it literally. If the paintings were simply scraps of a single giant canvas, they could be reassembled. And if they were reassembled, what picture formed? We were being fed, morsel by morsel, a grand design. ‘A representation of spatial relationships’ was how she described it. Her work, she said, involved sensing patterns in space – finding sites that were special confluences of abstract qualities, where the curving lines of a variety of economic, geographic and demographic variables converged. A kind of modern geomancy, a matter of instinct as much as calculation. She had a particular gift for seeing these patterns, any patterns. And the paintings formed a pattern. She was certain.

After midnight and after whisky, the idea found some traction with me. But in the morning, with the lights on, it sounded absurd. The artwork before me was simply banal, and I could not see that multiplying it would do anything but compound its banality. A chocolate-coloured mass filled the lower part of the frame, with an echoing, paler – let’s say latte – band around it or behind it, and a smaller, mocha arc to the upper left. Assigning astral significance to such a mundane composition was, frankly, more than simply eccentric, it was deranged. She had spent too long looking for auspicious sites and meaningful intersections for hotels, and was applying her divination to areas where it did not apply. I tried to trace the lines of the painting beyond the frame, to imagine where they might go next, extrapolating from what I could see. Spheres. Conjoined spheres. Nothing more. Spatial relationships – what did that even mean?

Spit, rinse. Bag, credentials, keycard. The shadows returned and I closed the door on them.

Music while waiting for the lift: easy-listening ‘Brown Sugar’. The lift doors were flanked by narrow full-length mirrors. Vanity mirrors, installed so people spend absent minutes checking their hair and don’t become impatient before the lift arrives. Mirrors designed to eat up time – there was some dark artistry, it’s true, but a decorators’ trick, not a cabalistic conspiracy. A small sofa sat in the corridor near the lift, one of those baffling gestures towards domesticity made by hotels. It was not there to be sat in – it was there to make the corridor appear furnished, an insurance policy against bleakness and emptiness.

In fact, given that this was a new hotel, it was possible, even likely, that no one had ever sat in it. An urge to be the first gripped me, but the lift arrived. Several people were already in it, blocking my view of infinity.

The first time I saw a hotel lobby, it was empty. Not completely empty, in retrospect: there were three or four other people there, a few suited gentlemen reading newspapers and an elderly couple drinking tea. And the hotel staff, and my father and mother. But my overriding impression was plush emptiness. Tall leather wing-back armchairs, deep leather sofas riveted with buttons that turned their surfaces into bulging grids. Lamps like golden columns, ashtrays like geologic formations, a carpet so thick that we moved silently, like ghosts.

Who was this fine place for? Surely not for me, a boy of six or seven – it had been built and furnished for more important and older beings. But where were they? When did they all appear?

‘Who stays in hotels?’ I asked my father.

‘Businessmen,’ my father said. ‘And travellers. Holidaymakers. People on honeymoon.’ He smiled at my mother, a complex smile broadcasting on grown-up frequencies I could detect but not yet decode. My mother did not smile back.

A waiter had appeared, without a sound. My father turned back to me, his smile once more plain and genial, eager to please his boy. ‘What would you like to drink?’

‘What is there?’

‘Anything you like.’

‘Coca Cola?’ I said, unable to fully believe that such a cornucopia could exist, that I could order any drink at all and it would be delivered to me.

Mother straightened like a gate clanging shut. ‘We mustn’t go off our heads with treats. How much will this cost?’ The question went to the waiter but her eyes were on me and my father, warning.

‘Darling, the company will pay.’

‘Will they? Do they know it’s for him? Is that allowed?’

‘They won’t know, and if they did, they wouldn’t mind. It’s just expenses.’

Expenses – another word freighted with adult mystery. Expenses, I knew, meant something for nothing, treats without consequences, the realm of my father; a sharp contrast to the world of home, which was all consequences. And expenses meant conflict, but not this time.

My father sold car parts, but he never called them car parts – they were always auto parts. Later, I learned specifics: he worked for a wholesaler and oversaw the supply of parts to distributors. This meant continual travel, touring retailers around the country. He was away from home three out of four nights, and at times for whole weeks. I yearned for the days he was home. We would go to the park, or go swimming – nothing I did not do with my mother, but the experience was transformed. He brought an anarchic air of possibility to the slightest excursion. A gleam in his eye was enough to fill me with mad joy. It was life as it could be lived, not as it was lived.

This was, in my father’s words, ‘a proper hotel’ – plush and slightly stuffy; English, not American; not part of a chain. It was in a seaside resort town, far enough from home for the company to pay for a room, but close enough for me and my mother to join him for a brief holiday, a desperate experiment in combining his peripatetic career with home and child-rearing. A fun and, much more important, normal time would be enjoyed by all – such was my mother’s anxiety on these points that she successfully robbed herself of any enjoyment. The hotel was quiet because it was off season. Winter coats were needed for walks along the grey beach; the paint was bright on the signs above the metal shutters, though the neon stayed unlit. The town was asleep, and we were intruders. In the hotel, we dined quietly among empty tables, an armoury of cutlery glinting unused, table linen like snow undisturbed by footsteps. I roamed the corridors. The ballroom was deserted and smelled of floor-polish. The banqueting hall was a forest of upturned chairs on tables. Everything was waiting for others to arrive, but who, and when? What happened here was of great importance and considerable splendour, but it happened at other times, and to unknown persons. Not to me.

Maybe my father moved in that world, where things were actually happening. There was a provisional air to him, as if he was conserving himself for other purposes. Even when he was physically present, he conducted himself in absences. He smoked in the garden and made and received telephone calls, speaking low. I would listen, taking care that he did not see me, trying to learn about the other world from what he said when he thought no one was listening. But he spoke in code: Magneto, camshaft, exhaust manifold, powertrain, clutch. And, rarer, another code: Yes, special, away, not until, weekend, she, her, she, she.

I was missing something.

The other lift passengers and I debarked into a lobby that had filled with people: sitting on the couches, standing in groups, talking on or poking at phones. Normally these communal places – the lobbies, the foyers, the atria – are barely used, inhabited only fleetingly by people on their way elsewhere, checking in or out, perhaps alone on a sofa waiting for someone or something. To see the space at capacity, teeming with people, was curiously thrilling, like observing by chance a great natural migration. This was it: I was present for the main event, when the hotels were at capacity and the business centres hosted back-to-back video conferences with head offices all over the planet. I could see it all for what it was and what it wasn’t. Because even when thronged with people, the lobby is still uninhabited – it cannot really be occupied, this space, or made home; it is a channel people sluice through. Those people sitting on the sofas don’t make the furniture any more authentic than the maybe-virgin seat I had seen by the lift. The space isn’t for anyone. My younger self might have been troubled by this thought, that even the main event could not give the space purpose – but now I had come to realise that the sensation was simple existential paranoia. I recognised the limits of authenticity.

Where there are buses, there is hanging around; Maurice’s dictum was quite correct. The driveway outside the hotel was protected by a porte-cochère. Under this showy glass and steel canopy, three coaches idled while conference staff in high-visibility tabards pointed and bickered, and desultory clusters of dark-suited guests smoked and hunched against blasts of cold, wet wind. The buses were huge and shiny, gaudy in banana-skin livery; their doors were closed. Evidently a disagreement or communications breakdown was under way – the attendants listened with fraught attention to burbling walkie-talkies, staring at nothing, or shouted at and directed each other, or jogged about, or consulted clipboards, but nothing happened as a result of this pseudo-activity.

I was about to retreat behind the glass doors, back to the warmth and comfort of the lobby, when I spotted Rosa (or Rhoda) standing alone among the huddle waiting for the buses, cigarette in one hand, phone apparently fused to the other. She had put on a brightly coloured quilted jacket and seemed unbothered by the cold and the icy raindrops that the wind pushed under the shelter.

‘Hey,’ I said.

Rosa looked at me without obvious emotion, although her neutrality could be read as wariness. ‘Hey.’

‘What’s going on?’ I said, nodding in the direction of the buses, where frenzied stasis continued. She looked momentarily dejected, and shrugged. We would never know, of course. The cause of this sort of hold-up was rarely made clear, it was just more non-time, non-life, the texture of business travel. Hotel lobbies and airport lounges are built to contain these useless minutes and soothe them away with comfortable seats, agreeable lighting, soft music, mirrors and pot plants.

‘I’m sorry we didn’t get much of an opportunity to talk back there,’ I said. Rosa’s edge of frostiness towards me, her shrugs and monosyllables, bothered me. I was certain we had got on well in the past, and she seemed an excellent candidate for some conference sex, if we could get past this froideur. My failure to capitalise on the coincidence in the bar last night had left a sour aftertaste. Some sex would dispel that; it would divert me, at least. If Rosa reciprocated.

‘You seemed busy,’ she said.

‘Nothing important.’

‘Who was that man who joined us?’

‘Maurice? I thought you knew him. A reporter, for a trade magazine.’

‘I’ve seen him around.’

‘He’s hard to miss.’

‘A friend of yours?’

‘Not really.’

‘So this girl he mentioned …’

Sexual jealousy, was it? That was a promising sign.

‘You shouldn’t believe a word Maurice says,’ I said. ‘He was only trying to stir up trouble. I was having a drink with an acquaintance. You know how you keep running into the same people at these things. Which can be a very good thing.’

‘Yeah.’ I was rewarded with a shy smile. Pneumatics hissed – one of the buses was opening its doors at last.

I decided not to overplay my hand – there would be other opportunities. ‘Really good to see you again,’ I said. ‘Let’s talk later.’

‘Sure,’ she said. ‘I’d like that.’ Her mobile phone, briefly removed from the social mix, reappeared like a fluttering fan.

Boarding the bus, I felt heartened by the encounter. It wouldn’t be too difficult after all.

The bus filled quickly, but there was a further mysterious delay before it got moving. Still, it was warm and dry, and the throbbing engine was as soothing as the ocean. The air had a chemical bouquet – new, everything was new. I stared at the patterned moquette covering the seat in front of me. Blue and grey squares against another grey. Hidden messages, secret maps? No, just a computer-generated tessellation reiterating to infinity. People milling around outside. New tarmac. A woman sat in the seat next to mine; I appraised her with a half-glance and found little that interested me. She ignored me and thumbed her phone, her only resemblance to Rosa.

Movement. One of the organisers appeared at the front of the bus, craning her neck as if looking for someone among the passengers. The bus doors closed with a sigh; the organiser sat down. The engine changed its pitch and we moved off.

We drove along an access road parallel to the motorway. The motorway itself was hidden from view by a low ridge engineered to deaden the howl of the high-speed traffic. The beneficiaries of this landscaping were a row of chain hotels: the Way Inn behind us, ahead a Novotel, a Park Plaza and a Radisson Blu, all in the later stages of construction, surrounded by hoardings promising completion by the end of the year. Here was the delayed skywalk: an elegant glass-and-steel tube describing most of an arch over the access road, the ridge and the unseen motorway, but missing a central section, the exposed ends sutured with hazard-coloured plastic. On the Way Inn side of the road, the skywalk joined the beginnings of an enclosed pedestrian link between the hotels at the first-floor level. Eventually guests would be able to stroll to the MetaCentre in comfort, protected from the climate and the traffic, but only the Way Inn section was finished. Perhaps all this construction work was evidence of industry, investment, applied effort – but the scene was, as far as I could see, deserted. There were no other vehicles on the road.

Signs warned of an approaching junction and myriad available destinations. The bus circled the intersection, giving us a glimpse down on-ramps of the motorway beneath us, articulated lorries thundering through six lanes of filthy mist, and then of the old road, a petrol station’s bright obelisk, sheds, used cars. We didn’t take either of those routes. Instead the bus turned onto another access road, again parallel to the motorway, but on the opposite side. A vast object coalesced in the drizzle: eight immense white masts in two ranks of four suggesting the boundary of an area the size of a small town, high-tension steel crosshatching the air above. The MetaCentre. My first instinct was to laugh. For all its prodigious size and expense, and the giddying alignment of business and political interests it represented, there was something very basic about it. It was, in essence, a giant rectangular tent, with guy ropes strung from the masts supporting its roof, keeping the rain off the fair inside. Plus roads and parking. So there it was, the ace card for the economic planning of this whole region: a very big dry place that’s easy to get to. And easy to see – the white masts, as well as holding up the immense space-frame roof, were a landmark to be noticed at speed from the motorway; while from a circling plane, the white slab would glare among the dull grey and brown of its hinterland.

The bus was off the access road now, onto the MetaCentre’s own road network: bright yellow signs pointed to freight loading, exhibitors’ entrances, bus and coach drop-off. Flowerbeds planted with immature shrubs were wrapped in shiny black plastic, a fetishist’s garden. There, again, was the ascending loop and expressive steel and glass of the unfinished pedestrian bridge. A handshake the size of a basketball court dominated the white membrane of the façade, overwritten with the words WELCOME MEETEX: TOMORROW’S CONVENTIONS TODAY. This was accompanied by multi-storey exhortations from a telepresence software company: JOIN EVERYONE EVERYWHERE.

A zigzag kerb, coaches nosing up to it diagonally. We dropped out of the front door one by one in the stunned way common to bus passengers, however long their journey. But we recovered quickly – no one lingered in the half-rain – and we scurried towards the endless glass doors of the MetaCentre, past an inflatable credit card that shuddered and jerked against the ropes securing it to the concrete forecourt.

Hot air blasted me from above, a welcoming blessing from the centre’s environmental controls. Thinking about my hair, I ran a hand through it, a wholly involuntary action. Grey carpet flecked with yellow. Behind me, someone said, ‘Next year we’re going to Tenerife, but I don’t want it to be just a box-ticking exercise.’ Queues navigated ribboned routes to registration and information desks. Memory-jogged, I fished my credentials out of my jacket pocket and slipped the vile lanyard over my head. Door staff approved me with a flicker of their eyes.

A broad ramp poured people down into the main hall of the MetaCentre. Gravity-assisted, like components on a production line or animals in a slaughter-house, we descended, enormous numbers of us – a whole landscape shaped to cope with insect quantities of people. Hundreds of miles of vile yellow lanyard had been woven, stitched with METACENTRE METACENTRE METACENTRE thousands of times to be draped around thousands of necks now prickling in the bright light and outside-inside air of the hall. Ahead of us, and already around us, were the exhibitors, in their hundreds, waiting for all those eyes and credentials and job titles to sluice past them. There is the expectant first-day sense that business must be transacted, contacts must be forged, advantages must be gleaned, trends must be identified, value must be added, the whole enterprise must be made worthwhile. Everyone is at the point where investment has ceased and the benefits must accrue. A shared hunger, now within reach of the means of fulfilment. Like religion, but better; provable, practical, purposeful, profitable.

At another fair, in other company, these thoughts might have been mine alone. Not here. All those thousands of conferences, expos and trade fairs around the world, of which I have attended scores if not hundreds – their squadrons of organisers comprise, naturally enough, an industry in itself. And, also naturally enough, this industry revels in get-togethers. It wants, it truly needs, its own conferences, meetings, summits and expos. Its people spend their lives selling face-to-face, handshake, eye contact, touch and feel, up close and personal, in the flesh, meet and greet. They believe their own pitch – of course they do. They actually think they are telling the truth, rather than just hawking a product. (Our pitch is very different.)

A conference of conference organisers. A meeting of the meetings industry. And they all knew the recursive nature of their gathering here – they all joked about it, essentially telling the same joke over and over, draining it of meaning until it is nothing more than a ritualised husk, but they laugh all the same. Just a conference of conference organisers, one among many – Meetex joins EIBTM, IMEX, ICOMEX, EMIF and Confex on the calendar, and all of those will include the same jokes and the same small talk, redundancy piled on redundancy, spread out across the globe. This repetition proliferating year after year was enough to bring on a headache. And indeed a headache had stirred since I left the hotel, accelerated perhaps by the stuffy bus and its throbbing engine, its boomerang route, the swinging 360-degree turn it had made around the motorway junction.

Hosting Meetex was a smart move by the MetaCentre – this space, which could swallow aircraft hangars whole, was in a way the biggest stall at the fair, advertising its services to the people who, captivated by its quality as a venue, would fill it with gatherings of other industries in the coming years. The airport! The motorway! The convenience! The state-of-the-art facilities! The thousands of enclosed square metres! A space without architecture, without nature, where everything outside is held at bay and there is no inside – no edges, the breezeblock walls too distant to see, a blankness above the steel frame supporting scores of lights. But inside this hall was a space with too much design. The fair, the exhibitors, all exhibiting. It was an assault on the eyes, a chaos of detail, several hundred simultaneous demands on your attention. And it was active, it came to you with bleached teeth and a tight T-shirt. Many stands were attended by attractive young women, brightly dressed and full of vim; there must be an inoffensive technical term for them, perhaps along the lines of ‘brand image enhancement agents’, but they are mostly referred to as booth babes. They jump out at you, try to coax you to try a game or join a list, or they hand you a flier or a low-value freebie like a USB stick or a tote bag.

Combined, these multitudinous pleas – each an invitation to enter a different corporate mental universe and devote yourself to it; invitations that are the product of enormous investments of time and money and creativity – formed a barrage of imagery and information and signs and symbols that at first challenged the brain’s ability to process its surroundings, becoming an undifferentiated blaze of visual abundance, overwhelming our monkey apparatus like lens flare. Which was precisely the point – it was in the interest of the organisers and the host to dazzle you, to leave the impression that there’s not just enough on show, there’s more than enough, far more than enough, a stupefying level of surplus. For a fair to imply that it might have limits is anathema – that’s why they rain down the stats and the superlatives, the square metres and the daily footfall, the record numbers of this and that. What other industry stressed that its product was near-impossible to consume? No wonder my services were needed. Adam was a genius.

It wasn’t impossible to see a whole show on this scale, but it was difficult. It took work. You had to be systematic, go aisle by aisle, moving up the hall in a zigzag, giving every stand some time but not so much time that it diminished the time given to others. That used to be my approach, but I found that route planning and time management occupied more of my thoughts than the content of the show itself. I was lost in the game of trying to see every stand, note every new product and expose myself to every scrap of stimuli – the show as a whole left only a shallow track on my memory. And my reports were similarly shallow. They were even-handed but lacked any texture; they were mere aggregations of data. In being systematic, I saw only my own system. Completism was blindness: it yielded only a partial view.

After a year of trudging around fairs in this manner, I realised my reports were formulaic and stale, full of ritual phrases and repeated structures. And the entire point of the endeavour was to spare clients that endless repetition. They employed me because they already knew the routine aspects of these fairs or didn’t care to know them – what they wanted was something else. So I threw away my diligent systems and timetables and started to truly explore. Today was typical of my current method of not having a method – I would strike out into the centre of the hall, ignoring all pleas and distractions, and from there walk without direction. I would try to drift, to allow myself to be carried by the current and eddies of the hall, thinking only in the moment, watching and following the people around me. Beyond that, I tried to think as little as possible about my overall aims and as much as possible about what was in front of me at any given time. I would give myself to the experience, keep my notes sparse, take a few photos. It’s not easy to be purposefully random, but it pays. Once I started taking this approach, my reports became colourful and impressionistic. They were filled with telling details and quirky insights. The imperfection of memory became a strength.

It’s only on the second and subsequent days of a fair that I seek out the specifics that clients have requested and conduct any enquiries they might have asked for. More detail accrues naturally, organically, around these small quests.

Surrounded by conference organisers, I am the only professional conference-goer. It’s what I do; nothing else. And they – the people here, the exhibitors, the venues, the visitors, the whole meetings industry – have no idea.

The stands passed by, hawking bulk nametags, audiovisual equipment, seating systems, serviced office space. Not just office space – all kinds of space are packaged and marketed here, and places too. You can get a good deal, a great deal, on Vietnamese-made wholesale tote bags at Meetex, but what it and its competitors mostly trade in is locations. Excuse me, ‘destinations’. Cities, regions, countries; all were ideal for your event, whether they were Wroclaw, Arizona or Sri Lanka, or Taipei, Oaxaca or Israel. All combined history and modernity. All were the accessible crossroads of their part of the world. All were gateways and hearts. All had state-of-the-art facilities that could be relied upon. All had luxurious yet affordable hotels. Most importantly, all of these hundreds of places across the world were distinctive, unique and outstanding. Consistently, uniformly so.

Those comfortable, cost-effective hotels and state-of-the-art facilities were also present at Meetex. Other conference centres promoted themselves, boasting of the inexhaustible square kilometres they had available on scores of city outskirts. Within a giant space, I was being coaxed to other giant spaces; a fractal shed-world, halls within halls within halls.

Another section was devoted to the chain hotels, and its promises of pampering and revitalisation were hard to bear. Women wrapped in blinding white towels, cucumber slices over eyes. Men, ties AWOL, drinking beer in vibrant bars. Couples clinking capacious wine glasses over gourmet meals. Clean linen, gleaming bathrooms, spectacular views. These were highly seductive images for me. I wanted to be back at the hotel, reclining on the bed, taking a long shower, ordering a room service meal, perhaps with some wine thrown in.

It mattered little that the images were a total fiction – posed by models, supplied by stock photo agencies, the gourmet food made of plastic, the views computer generated, the bar a stage set – the desire they generated was real. Meetex was dominated by these deceitful images, defined by them. The location on sale is immaterial. The picture, the money shot, is nearly identical everywhere: a gender-mixed, multicultural group unites around an arm-outstretched, gap-bridging handshake, glorying in it; gameshow smiles all round, with an ancient monument or expressive work of modern architecture as the backdrop. Business! Being Done! The transcendent, holy moment when The Deal is Struck. Everyone profits! And in unique, iconic, spectacular surroundings, heaving with antiquities and avant-garde structures, the people bland and attractive, their skin tones a tolerant variety but all much alike, looking as if they have just agreed the sale of the world’s funniest and most tasteful joke while standing in the lobby of a Zaha Hadid museum.

If only they looked around. Business was done in places like the Way Inn, or in giant sheds like the MetaCentre. Properly homogenised environments, purged of real character like an operating theatre is rid of germs. Clean, uncorrupt. That’s where deals are struck – in the Grey Labyrinth. And that’s where I headed, because I had business to attend to.

The Grey Labyrinth took up the rear third of the centre’s main hall. This space was set aside for meetings, negotiations and deal-making, subdivided into dozens of small rooms where people could talk in private. It was the opposite of the visual overload of the fair, a complex of grey fabric-covered partitions with no decoration and few signs. All sounds were muffled by the acoustic panels. The little numbered cubicles were the most basic space possible for business – a phone line, a conference table topped with a hard white composite material, some office chairs. Sometimes they included a potted plant, or adverts for the sponsor company that had supplied the furnishings. Mass-produced bubbles of space, available by the half-hour, where visitors video-conferenced with their home office or did handshake deals. They loved to talk about the handshake, about eye contact, about the chairman’s Mont Blanc on a paper contract – these anatomical cues you could only get from meeting face to face. They wanted primal authenticity, something that could be simulated but could never be equalled. But it all took place in a completely synthetic environment – four noise-deadening, view-screening modular panels, a table, some chairs, a phone line. Or, nowadays, a well-filled wifi bath in place of the latter.

I had booked cubicle M-A2-54 for 10.30 a.m. It was empty when I arrived, four unoccupied office chairs around a small round table. A blank whiteboard on a grey board wall. No preparation was needed for the meeting and I sat quietly, drumming my fingers on the hard surface of the table, listening to the muted sounds that carried over the partitions.

The prospect was seven minutes late, but I didn’t let my irritation show when he arrived, and greeted him with the warm smile and firm handshake I know his kind admire.

‘Neil Double. Pleasure to meet you.’ False – I am indifferent about the experience. Foolish to place so much faith in a currency that is so easily counterfeited.

‘Tom Graham. Likewise.’ Graham was an inch or two shorter than me but much more substantial – a man who had been built for rugby but, in his forties, was letting that muscle turn to butter in the rugby club bar. His thick neck was red under the collar of his Thomas Pink shirt. Curly black hair, sprinkled with grey, over the confident features of a moderately successful man. We sat opposite each other.

‘So, Tom, why are you here?’

He jutted his bottom lip out and made a display of considering the question.

‘A friend told me about your service, and I wanted to find out more about it.’

Word of mouth, of course – we don’t advertise.

‘I meant,’ I said, ‘why are you here at the conference? Aren’t there places you would rather be? Back at the office, getting things done? At home with your family?’

‘Aha,’ Tom said. ‘I see where you’re going.’

‘Conferences and trade fairs are hugely costly,’ I said. ‘Tickets can cost more than £200, and on top of that you’ve got travel and hotel expenses, and up to a week of your valuable time. And for what? When businesses have to watch every penny, is that really an appropriate use of your resources?’

‘They can be very useful.’

‘Absolutely. But can you honestly say you enjoy them? The flights, the buses, the queues, the crowds, the bad food, the dull hotels?’

Tom didn’t answer. His expression was curious – not interested so much as appraising. I had an unsettling feeling that I had seen him before.

I continued. ‘What if there was a way of getting the useful parts of a conference – the vitamins, the nutritious tidbits of information that justify the whole experience – and stripping out all the bloat and the boredom?’

‘Is there?’

‘Yes. That’s what my company does.’

I am a conference surrogate. I go to these conferences and trade fairs so you don’t have to. You can stay snug at home or in the office and when the conference is over you’ll get a tailored report from me containing everything of value you might have derived from three days in a hinterland hotel. What these people crave is insight, the fresh or illuminating perspective. Adam’s research had shown that people only needed to gather one original insight per day to feel a conference had been worthwhile. These insights were small beer, such as ‘printer companies make their money selling ink, not printers’ or ‘praise in public, criticise in private’. But if Graham got back from a three-day conference with three or four of those ready to trot out in meetings, he’d feel the time had been well spent. That might sound like a very small return on investment, and it is, but these are the same people who will happily gnaw through cubic metres of airport-bookshop management tome in order to glean the three rules of this and seven secrets of that. Above those eye-catching brain sparkles, a handful of tips, trends and rumours is all that sticks in the memory from these events, and they can get that from my report, plus any specific information they request. Want to know what a particular company is launching this year? Easy. Want a couple of colourful anecdotes that will give others the impression you were at the event? Done. Just want to be reassured that you didn’t miss anything? My speciality.

And if you want to meet people at the conference, be there in person, look people in the eye and press the flesh – well, we can provide that as well. I’ll go in your place. Companies use serviced office space on short lets, the exhibitors here have got models standing in for employees and they use stock photography to illustrate what they do. That pretty girl wearing the headset on the corporate website? Convex can provide the same professional service in personal-presence surrogacy. We can provide a physical, presentable avatar to represent you. Me. And I can represent dozens of clients at once for the price of one ticket and one hotel room, passing on the savings to the client.

Of course I still have to deal with the rigmarole of actual attendance, but the difference is that I love it. Permanent migration from fair to fair, conference to conference: this is the life I sought, the job I realised I had been born to do as soon as Adam explained his idea to me, at a conference, three years ago. It is not that I like conferences and trade fairs in themselves – they can be diverting, but often they are dreary. In their specifics, I can take them or leave them – indeed, I have to, when I am with machine-tools manufacturers one day and grocers the next. But I revel in their generalities – the hotels, the flights, the pervasive anonymity and the licence that comes with that. I love to float in that world, unidentified, working to my own agenda. And out of all those generalities I love hotels the most: their discretion, their solicitude, their sense of insulation and isolation. The global hotel chains are the archipelago I call home. People say that they are lonely places, but for me that simply means that they are places where only my needs are important, and that my comfort is the highest achievement our technological civilisation can aspire to. When surrounded by yammering nonentities, solitude is far from undesirable. Around me, tens of thousands are trooping through the concourses of the MetaCentre, and my cube of private space on the other side of the motorway has an obvious charm.

Tom Graham appeared to be intrigued by conference surrogacy, and asked a few detailed questions about procedures and fees, but it was hard to tell if he would become a client or not. And if he did sign up, I wouldn’t necessarily know. Discretion was fundamental to Adam’s vision for our young profession – clients’ names were strictly controlled even within the company, as a courtesy to any executives who might prefer their colleagues not know that someone was doing their homework for them. Today, for instance, I knew that clients had requested I attend two sessions, one at 11.30 and one at 2.30, but I had no idea who or why. After the second session, my time would be my own – I could slip back to the hotel for a few hours of leisure before the party in the evening.

A few hours of leisure … The thought of my peaceful room, its well-tuned lighting, its television and radio, filled me with a sense of longing, the strength of which surprised me. It was almost a yearning. Right now, I imagined, a chambermaid would be arranging the sheets and replacing the towel and shower gel I had used. Smoothing and wiping. Emptying and refilling. Arranging and removing. Making ready.

Also, a return to the hotel would give me another chance to encounter the redheaded woman – a slim chance, but it was an encounter I was ever more keen to contrive. Her continual reappearance in my thoughts was curious to me, and almost troubling – a sensation similar to being unsure if I had locked my room door after I left. Her shtick about the paintings might have been a sign that she was a miniature or two short of a minibar, but it had only increased her mystique. She was unusual – of course, that had been obvious the first time I saw her, years ago. Beautiful, too. And there was something about the rapture with which she described the potential of the motorway site, its existence at the nexus of intangible economic forces … she knew these places, she had some deeper understanding of them.

After I had said my goodbyes to Tom and left the muffled solemnity of the Grey Labyrinth, the jangling noise and distraction of the fair were unwelcome, so I fled into the conference wing to find the first session. There, I found some peace. The seats were comfortable, the lighting was dimmed for the speaker’s slides. It was straightforward stuff: business travel trends in the age of austerity. I jotted down a few of the facts and statistics that were thrown out. Tighter cashflow, fewer, shorter business trips and less risk-taking meant potential gains for the budget hotels. Michelin stars in the restaurant and the latest crosstrainers in the gym were much less important than reliable wifi, easy check-in and a quiet room. Good times for Way Inn, and for me. It was reassuring, almost restful, stuff. For some of the session, I was able to come close to drowsing, letting my eyelids become heavy and enjoying being off my feet. The end of the talk was almost a disappointment. Applause was hearty.

I was beginning to feel that a peaceful routine had been restored – a sensation that was a surprise to me, because until that point I had not realised that my routine had been disrupted. Maybe I wasn’t getting enough sleep. Maybe, instead of pursuing Rosa or the redheaded woman into the night, I should get to bed early, spend some quality time in the company of freshly laundered hotel linen.

But first, lunch. There were various places to eat in the MetaCentre, and like an airport or an out-of-town shopping centre – anywhere with a captive audience, in fact – they were all likely to be overpriced and uninspiring. Rejecting branded coffee shops and burger joints, I headed for the main brasserie. In less image-conscious times, this would simply be called a canteen: big, bright and loud, serving batch-prepared food from stainless-steel basins under long metres of sneezeguard. A hot, wet tray taken from a spring-loaded pile and pushed along waist-height metal rails; a can of fizzy drink from a chiller, a cube of moussaka from a slab the size of a yoga mat; green salad in a transparent plastic blister. It might sound awful, but it was fine, really, just fine. I was eating alone and had no desire to linger – there was no need for me to be delighted by exotic or subtle flavours, and any attempt to pamper me would surely have been a delay and a provocation. It was good, simple, efficient, repeatable, forgettable. For entertainment, I sorted through some of the fliers and cards I had picked up from the fair. To carry these, I had brought my own tote bag, one from a fair last year which had unusually low-key branding. In my line of work, you never run short of totes.

In the MetaCentre’s central hall, even within the perplexing grid of the fair, navigation was not too hard: giant signs suspended from the distant ceiling identified cardinal points, and if you somehow managed to really, truly lose your sense of where you were, you could simply walk towards the edge of the hall and work your way around from there. In the wings of the centre, formidable buildings in themselves, a little more spatial awareness was needed. To find the venue of the second session on my schedule for the day, I had to consult one of the information boards that stood helpfully at junctions in the miles of passage and concourse. Before me, the conference wing was sliced into its three floors, splayed out like different cuts at the butcher’s and gaily colour-coded. I began to plot my course from the brasserie to the correct auditorium: Meta South, east concourse, S3 escalators …

This locative reverie was obliterated by a hard, flat blow between my shoulder blades, delivered with enough force to knock the strap of my tote bag from my shoulder. I wheeled around, part ready to launch a retaliatory punch even as I experienced sheer unalloyed bafflement that anybody could be so assailed in a public place, in daylight. What greeted me was a wobbly smile, wrinkled linen and strands of blond hair clinging to a pink brow.

‘Afternoon, old chap. I say, I didn’t take you off guard, did I?’

‘Jesus, Maurice,’ I said. ‘What the hell do you think you’re playing at?’

Maurice put up his hands. ‘Don’t shoot, commandant!’ He chuckled, a throaty, rasping gurgle. ‘Don’t know my own strength sometimes, it’s all the working out I do.’ Comic pause. ‘Working out if it’s time for a drink!’ The chuckle became a smoker’s laugh, and he broke his hands-up pose to wave me away, as if I was being a priceless wag.

‘You startled me,’ I said, stooping to pick up my bag.

‘So what’s in store next?’ Maurice asked, leaning over me to examine the map. I became uncomfortably aware of the proximity of my head to his crotch. The crease on his trouser legs was vestigial, its full line only suggested by the short stretches of it that remained, like a Roman road. ‘You going to “Emerging Threats”?’

‘Yes,’ I said, straightening. I wanted to curse. Trapped! It would be impossible to avoid sitting next to Maurice, and there was no way to skip it: ‘Emerging Threats to the Meetings Industry’ had, after all, been requested by a client. Sitting next to Maurice meant having to put up with his fidgeting, lip-smacking and sighing, and a playlist of either witless asides or snores. It had all happened before. And afterwards he would ask what I was doing next and if I said I was going back to the hotel there was a very real risk he would think that a fine idea and decide to follow me, and we would have to wait for a bus together and sit on it together, or I would have to spend time devising an escape plan, inventing meetings and urgent phone calls … the amount of additional energy all this would consume was, it seemed to me, almost unbearable. I wanted to lock the door of my hotel room, lie on the bed and think about nothing.

‘Bit of time, then,’ Maurice said, looking at his watch. ‘I’m glad I ran into you again actually, there’s something I keep forgetting to ask you. Do you have a card?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘A card, a business card. I’m sure you gave me one ages ago but’ – he rolled his eyes in such an exaggerated fashion that his whole head involved itself in the act – ‘of course I lost it.’

For a moment I considered denying Maurice one of my cards – it would be perfectly easy to claim that I hadn’t brought enough with me that morning and had already exhausted my supply – but I decided such a course was pointless. The cards were purposely inscrutable and were intended to be given out freely without concern. Just my name, the company name, an email address, a mailing address in the West End and the URL of our equally laconic website. I gave Maurice a card. He made a show of reading it.

‘Neil Double, associate, Convex,’ Maurice recited in a deliberately grand voice. ‘Ta. What is it you do again?’

‘Business information,’ I said. I am quite good at injecting a bored note into the answer, to suggest that nothing but a world of tedium lay beyond that description.