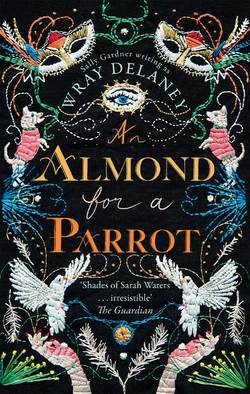

Читать книгу An Almond for a Parrot: the gripping and decadent historical page turner - Wray Delaney, Wray Delaney - Страница 13

ОглавлениеChapter Seven

Hodgepodge of All Sorts of Meat

Take an earthen pot, well scalded, and put into it four pounds of the loin of mutton, two pounds of filleted veal, one partridge, two large onions, two heads of cloves, one carrot and a quart of water; put a paste made of flour and water round the cover to keep in the steam; place this pot within another somewhat larger, and fill up the vacancies between the two pots with water; let them simmer or stew for seven or eight hours, taking care to supply the outer pot with boiling water so that the meat in the inner pot may be constantly stewing; when done, sift the broth through a sieve, let it settle, and then sift a second time through a napkin; serve the meat and the broth together in a terrine.

My other tutor, Mr Smollett, was an earthbound weasel of a man whose nose caused him no end of trouble, as did his pious beliefs, all being equally irksome. He arrived every morning clutching a prayer book to his pinched-in body. No doubt, as a boy, he had been told how tall a man should grow and when finding himself beyond the mark, felt obliged to shrink the difference into his shoulders.

He seemed to be only concerned with the vices that were to be discovered at the theatre and the coffee house, so that as well as being pinched in body, he was pinched in mind. By degrees it became clear to me that Mr Smollett was nothing more than a hypocrite, for, behind all his condemnation of the city of sin, I could tell the level of excitement the subject brought him to by the dribbles that fell from the end of his troublesome nose.

After a while I could read fluently. Books I liked, but I was bored with all that dull Mr Smollett had to say and I wasn’t paying much heed when one day he announced he was going to talk on the cause of all evil in the world. I think this may have been brought about by my exceedingly low-cut bodice. Mrs Truegood had told the dressmaker to accentuate my natural assets and the effect of my assets on Mr Smollett resulted in a lecture on the electrical influence of the female root on the male root. For the first time Mr Smollett had my undivided attention.

‘I will endeavour to explain,’ he said, ‘but I am sure it is beyond your comprehension.’ Seeing that his speech wasn’t received with the usual posy of yawns he carried on. ‘The male root can grow to between seven and twelve inches long. The top is carnation in colour, softer than a petal to touch. At the base there are two globes, bound to the stem of the root. The outside of the bags is wrinkly and covered with a kind of down, much resembling the hair on a beard of corn.’ He paused, then with his chest puffed out, said, ‘But as soon as this magnificent root is under the influence of the female root, it rises itself to become as stiff as a poker and remains so until the electrical fire is spent, which is known by a plentiful eruption of glutinous matter.’

‘What about the female… root?’ I asked.

Sweat salted his forehead and his cheeks went claret. He took out his kerchief and blew his nose so hard that his wig became somewhat lopsided.

‘The mouth and the whole appearance of the female root is often covered with a bushy kind of hair,’ he said, his eyes never leaving my assets. ‘It is a broad root within which a hole is perforated. The hole contracts or dilates like the mouth of a purse. To look at it you would never imagine that you could put anything into it at all, let alone a male root. But upon travail, it will dilate so much as to receive a rolling pin.’

After this pretty speech, Mr Smollett suddenly excused himself from the chamber. He came back adjusting his breeches, somewhat calmer.

I hoped he might talk further on the matter. He didn’t, though henceforth his attitude towards me became more familiar. He would insist that I sat on his lap while I read to him. That way, he said, it would be easier for us both to see the words. Being a good girl I did as I was told. I could feel the root of him go poker hard. I didn’t find it without interest and would have been more engaged if its owner hadn’t repulsed me quite as much Mr Smollett did.

There had been many sea changes in the house since my father had remarried, and he grew to doubt that he was still the captain of his ship. Mrs Truegood insisted that new linen mattresses were bought and the old, moth-worn, flea-ridden mattresses be burned. My father almost choked at the very notion, but one look from my stepmother shipwrecked any complaints he might have harboured. She also stated that wives and husbands who slept in separate beds had healthier nerves and stronger spirits than those who slept together. My father roared like bedlam and fell to swearing, but all for naught. His new wife remained unmoved and, deaf to his pleas, ordered a drink be made for him of sage, rosemary and sarsaparilla, which she said was good for a troubled temperament.

So it was that Mrs Truegood kept to her own set of rooms and my father reluctantly to his, and never the two did meet so it seemed to me, for I would have heard the floorboards creak and I never did.

My lessons with Mr Smollett continued and my curiosity – nay, I will call it hunger – to know more about roots would have led me into ruin if Mercy hadn’t taken it upon herself to save me.

I had slept so long with Cook, and was so used to her snores and farts and the smell of the sheets, that I found my new bed a little cold and was delighted when Mercy asked me to share hers. She said it was too wide, and Hope had her own bedchamber as she was to be married and consequently needed time alone.

The first night, I found her half undressed while her maid folded her clothes. Mercy’s bedchamber smelled of oranges and had a bookcase full of novels. She was not in the least bit shy to be seen half naked. She had next to no bubbies at all on her boyish figure.

‘I sleep on the right,’ she said, ‘with a pistol under my pillow.’ I must have looked truly alarmed, for she burst out laughing. ‘No, no, of course I don’t, you noodle.’

She kissed me on the cheek and said she was pleased to have my company. In the nights that followed we often talked, or she would read to me. Before she blew out the candle she would turn and kiss me goodnight.

No one had ever shown such tenderness to me before and, for reasons I couldn’t fathom, with each of her kisses not so much an ache but more a curious itch began to trouble me. I lay in the dark and wished my body wasn’t such a riddle to me. One night everything changed.

I remember waking from a nightmare. I dreamed that a man whose face I couldn’t see was trying to push me into a chamber. He threw the door open and inside were three women, tied by their hair to three metal rings that hung from the ceiling. I pulled away from him and I found myself falling down an endless stairwell.

I must have shouted out in my sleep for I woke to find the candle alight and Mercy looking down at me.

‘It’s all right,’ she said and kissed me gently on the lips. ‘It’s a nightmare, nothing more.’

She put her arms round me and held me to her, rocking me. I found myself returning her kisses and with each peck the ache became stronger until I was desperate for relief from it. Mercy asked if I felt calmer and all I could do was nod. She blew out the candle, turned over, and promptly fell to sleep. I lay wide awake, certain I must be ill for the surely the ache shouldn’t have returned at Mercy’s kiss. A terrible thought occurred to me that I was truly sick and there was no cure. I stared into the darkness, sobbing, as lost as midnight. Mercy stirred once more and asked sleepily what was wrong.

‘Mercy, I think I have a fever,’ I blurted out.

‘Oh, no, my dear,’ said Mercy, hurriedly relighting the candle. ‘What is the matter?’

‘I have a terrible ache!’

‘Where?’ Mercy asked.

I couldn’t tell her, I was too embarrassed.

‘Where?’ she asked again.

‘In between my legs.’

‘Show me,’ she said.

I bunched up my nightdress so it was above my waist and pointed to my Venus mound.

Mercy fell back on the pillows in a fit of giggles. ‘My dear Tully. That is quality, so it is.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘When did this ache of yours start?’ she said, struggling to compose her face.

With eyes half closed and pulling my nightgown up further so that it hid my face, I made her promise not to whisper a word to any soul as to what I was about to tell her.

‘It started with the gentleman visitor.’

‘Oh sweet Lord. What gentleman?’ said Mercy.

I peeled back the nightgown from my eyes, for her voice had lost all its humour. I told her how the gentleman had found me as naked as the day I was born and how he had kissed me and how his fingers had the effect of making my body flame.

‘I thought it must be love. It seemed the only rational reason for the ache. But when you kissed me just now on the lips the same ache came back, so you see I think I must be ill.’

Mercy tried to stifle a laugh.

‘It’s not amusing,’ I said.

‘You are a noodle,’ she said. ‘You’re not ill. You’re as healthy as any other full-blooded female. Perhaps more so than others.’ She pulled the nightgown from my burning cheeks. ‘Shall I show you the remedy for your ache?’

‘Is there one?’ I asked.

‘Yes,’ she said and kissed me, her tongue sweeter by far than that of the gentleman in the blue chamber, and her fingers more gentle. My whole body ignited on the point of bursting into flame. Her mouth by degrees – and such delicious degrees – found their way to my globes and stayed there while her hands progressed further down in between my legs, which she gently parted. Her finger then went into my wet purse and found the spot of all my ache, a hard pearl which she attended to with such care that I thought I might go wild if there wasn’t some release. My whole body started quaking and I felt I could endure it no more when, to my utter surprise, there was an explosion followed by the most exquisite sensation and the ache burst into a thousand fragments of joy. I let out a cry as a flood of warmth and glory filled me, and all was peaceful.

Without thinking or even considering the right and the wrong of what had taken place, I put my arms round Mercy and kissed her.

‘That,’ she said, stroking my hair, ‘is the remedy for your ache.’

I woke to find that I was curled up in Mercy’s arms and that she too was naked. She had a flat stomach and her Venus mound was covered in a lush bush of black foliage. Waking, she looked at me and kissed me and asked how my ache was.

I smiled. ‘Better. But still there.’

‘So is mine,’ said Mercy.

She opened her legs and, taking my hand, guided it down to the spot and kissed me with such longing that I felt my ache return with a vengeance. Afterwards, I told Mercy what Mr Smollett had said about the root of all evil. She said she had never heard anything quite so silly, and was a far better tutor in every way than dull Mr Smollett. Shortly after this, Mr Smollett and his root vegetable came to a pretty pass, which proved to be a good thing for I would have been obliged to use force to deter him if it had gone any further.

Like the boot boy, he suddenly declared his undying love for me.

‘Mistress Truegood,’ he said, ‘I am on fire.’ And he took hold of my hand and placed it firmly on his vegetable patch.

I said nothing but decided that come feathers and dust this would be the last lesson I had with Mr Smollet.

‘You want to see the root of all evil,’ he cried. ‘I know you do. You want to feel the passion that cannot be denied.’

And before I could say that due to Mercy I was now in a much better position to wait a while, he had quite undone himself to reveal a rather disappointing upright carrot.

‘Mistress Truegood, touch me,’ he pleaded.

‘No thank you,’ I said, ‘I would rather not.’

‘Please,’ he said, grabbing hold of his small root. ‘Put me out of my misery.’

The door to the chamber burst open.

‘Happily, sir,’ came the stern voice of Mrs Truegood.

I watched fascinated as the carrot shrivelled and became only good for compost.

‘You will leave this instant,’ said my stepmother.

And to my delight, Mr Smollet and the root of all his evils did just that.

But having seen my tutor’s shrivelled vegetable made me realise that there was something missing from Mercy’s lovemaking, something I longed to experience: not Mr Smollett’s root of all evil, more a man who possessed a true pole of pleasure.