Читать книгу Journey to the West - Wu Cheng'en - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

(1) THE RECORD OF THE WESTERN REGIONS

THE JOURNEY TO THE WEST is based on a true story of a Buddhist monk, Xuanzang, and his pilgrimage to India to acquire the “true scriptures.” Buddhism had entered China from India during the Han dynasty, mainly as the religion of foreign merchants. It spread amongst the Chinese population after the fall of the Han, during the so-called Period of Division, when China was in a constant state of chaos, war, and misery. “I teach suffering,” said the Buddha, “and how to escape it.” This was very different message from the statecraft of Han Confucianism or the mixture of mysticism, magic, and local religion Taoism had become, and one which found a deep response in the anarchy China had disintegrated into at that time.

Xuanzang’s youth coincided with the reunification of China under the short-lived Sui dynasty. He was a precocious child, and received a scholarship (to use the modern idiom) to study in the Pure Land Monastery. When the Sui collapsed in 618, Xuanzang fled to Chang’an, where the new Tang dynasty had been proclaimed. He moved on to Chengdu in remote Sichuan where hundreds of monks had taken refuge. He later travelled throughout the country, learning from the local monks whatever he could about their understanding of Buddhism. He discovered they differed greatly amongst themselves, and came to realise the confusion and limitations on Chinese Buddhism due to a lack of authoritative, canonical texts. The Buddhist scriptures in China had been translated at different times and places, by translators of different levels of ability and understanding of Buddhist doctrines, even translations of translations of translations through the various languages of India and Central Asia. Xuanzang could see that beyond the confusion there was great Truth, but that that Truth could only be found in the original and genuine scriptures of Buddhism. That would entail going to India to get them. He had predecessors: the monk Faxian had visited India between 399 and 414, and had left a record of his travels. Xuanzang was already aware of the various schools of Indian Buddhism, and was particularly interested in acquiring the Sanskrit text of the yoga sastra, which taught that “the outside does not exist, but the inside does. All things are mental activities only.” That was the basis of the Consciousness Only School of Buddhism, founded in China by Xuanzang. Metaphysical and abstract, it did not become a popular school, but its influence persists. One of the major Chinese philosophers of the twentieth century, Xiong Shili, attempted a fusion of the precepts of this school with Confucianism, and this has influenced several generations of students of Chinese philosophy. On the popular level, anyone who has taken a course in meditation (of any variety) over the past few decades would have heard something along the same lines.

Xuanzang was 28 when he started on his pilgrimage to India. It was a pilgrimage with a purpose, altruistic and not personal: to bring the “true scriptures” to China for the salvation of lost souls. He spent sixteen years away, travelling from what is now Xi’an through Gansu, and from there through the oasis cities around the Taklamakan desert, into Central Asia, then through what is now Afghanistan to India. After his return to China he wrote a detailed geographical description of the lands he had passed through, with notes on the peoples, their languages and beliefs. This book is called Record of the Western Regions, in Chinese Xiyuji. The Chinese title of The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures is Xiyouji, a deliberate and direct reference to Xuanzang’s records of his travels. In the early twentieth century the Record of the Western Regions became a guidebook to many of the “foreign devils on the silk road.” Sir Aurel Stein was one of these, who convinced the curator of the secret library of Dunhuang that Xuanzang was his patron saint, thus persuading him to hand over large quantities of thousand year old manuscripts. Much in the way of Heinrich Schliemann with Homer in hand looking for Troy, Aurel Stein and the others relied on Xuanzang’s Record of the Western Regions as a guide, located long buried cities under the sands of the Taklamakan desert. Xuanzang, incidentally, visited Dunhuang on his way back to Xi’an—in fact he had been provided with an escort from Khotan, on the emperor’s orders. It is not known if the famous portrait in one of the caves is of Xuanzang, or another itinerant monk.

On his way to India, he passed through many kingdoms. In Turfan the king wanted to retain him to such a degree that he would not allow him to proceed, and only agreed after Xuanzang went on a hunger strike. The king was so impressed he provided him with an escort and provisions for the next part of the journey. He also wrote twenty-four letters of introduction to his fellow rulers of the small kingdoms of Central Asia through which Xuanzang would pass. They proceeded to the oasis of Kucha, another stop along the Silk Road, where the red haired, blue-eyed Tokharian ruler, a Buddhist, made him welcome. There he was able to debate with Hinayana Buddhists, who followed the “Lesser Vehicle” road to enlightenment, which was regarded as inferior by adherents of the Mahayana, or “Greater Vehicle,” which was the prevalent form of Buddhism in China. Such debates were to continue during Xuanzang’s travels, adding to his knowledge of the various schools of Buddhism within India itself.

During the seven days they spent crossing the Tianshan mountains, fourteen men, almost half their party, starved or were frozen to death. They went on to the camp of Yehu, the khan of the eastern Turks, where the letters of introduction from the king of Turfan were helpful. This khan also suggested that Xuanzang go no further, but eventually provided him with a Chinese speaking guide, who accompanied him as far as modern Afghanistan. He passed through Bamiyan, where he described the huge statues carved into the cliff, the same statues which were blown up by the Taliban only a few years ago. He then went to Tashkent and Samarkand, then on to Bactria, near Persia. The local ruler was Tardu, the eldest son of Yehu and the brother in law of the King of Turfan. Tardu’s wife had died, and he had married her younger sister, who immediately poisoned him. She and her lover then usurped the throne. It was here Xuanzang met Dharmasimha, who had studied Buddhism in India, and later Prajnakara, a monk from an area near Kashmir. Xuanzang was coming more and more into the Indian cultural sphere, but he yet had to physically cross the Hindukush into India itself.

When he crossed the Kabul River he was closer to places and events associated with the life of the Buddha. Buddhism was already in decline in India when Xuanzang visited, and many of the famous monasteries, once teeming with monks, were deserted and in ruins. He visited Sravasti, the site of the Great Hall where Buddha preached, Kapalivastu, where he was born and Kusinagara, where he died and was cremated. In one of the most moving passages in the book, when Xuanzang first approaches the bodhi tree, under which the Buddha had attained enlightenment, he threw himself face down and wept, wondering what sin he must have committed in a previous life to be born in Tang China and not in India during the lifetime of the Buddha himself.

For eight or nine days he could not bring himself to leave the holy tree, until some monks came from Nalanda monastery, India’s most prestigious place of Buddhist learning, to escort him there. The entire community of ten thousand monks came to greet him. He traveled throughout India, to Bengal and Orissa, and almost to Ceylon, but political turmoil there made it imprudent to visit. At one stage he was captured by pirates intending to sacrifice him, but a cyclone swept through the forest and the pirates were so scared they released him. Towards the end of his time in India, Xuanzang met the great Buddhist King Harsha, and explained his mission. Soon after this Harsha sent a delegation to Chang’an, thus establishing what we would now call diplomatic relations with China. Indian monks also urged Xuanzang to stay with them: India was the home of the Buddha, and China was such an unenlightened place it would be unlikely to attain Buddhahood there. Xuanzang explained that was precisely the point of his mission, and he made plans to return to China. During all this time in India, throughout his travels, he had been collecting scriptures and statues. It was now time to pack them up and return to China. He made elaborate preparations, and set off through terrain as difficult and dangerous as the way there. When he was crossing the mile-wide Indus River (on an elephant), his books and statues were thrown into the water by a sudden storm, and several were lost. Xuanzang had to send back to India for replacements before proceeding. His party consisted of seven monks, twenty porters, ten asses, four horses, and an elephant. He eventually arrived in Kashghar, and then Khotan, which he noted was famous for its jade market. At this point his fame had grown to the extent that the Tang emperor instructed the King of Khotan to provide an escort for Xuanzang and his group to Dunhuang, and from there to Chang’an. A vast crowd welcomed him home. Emperor Taizong met him personally, and asked him to write a detailed geographical description of the seventy or more kingdoms through which he traveled. The Record of the Western Regions was completed in 646. Until his death the pilgrim retranslated existing works, and translated previously unknown scriptures. He died not long after completing his translation of the long and complex Diamond Sutra. His best known translation in the modern world is the Heart Sutra, recited daily by millions of believers, and readily available in any modern Chinatown shop selling Buddhist statues and other religious items.

Increased interest in Buddhism, the Silk Road, and growing global awareness has made Xuanzang a significant figure in world history in the twenty-first century. Historically, he can also be considered an extremely influential figure: through him Buddhism, which was to die out in India, was translated to China, and a collection of confused and disconnected ideas which Buddhism was threatening to become was transformed into a profound and complex philosophical and psychological system. From China Buddhism spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Most of the philosophical schools of Tang Buddhism did not survive the fall of the Tang, one of the great watersheds in Chinese history. What did survive was the Pure Land School, which saw the aim of life as reincarnation in the Pure Land, where one could enjoy the blessings and avoid the sufferings of life on earth. This was to become the basis of popular Buddhism throughout China, and from there into the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia and beyond. The other school to survive was Chan, which did not rely on scriptures, but on meditation to reach enlightenment in a flash of inspiration. This was restricted to a few monasteries in China, particularly the Shaolin monastery, which combined Chan Buddhism with martial arts. Recent interest in Chinese martial arts and innumerable movies about fighting monks have attracted a certain interest in Chan Buddhism itself in recent years. Historically it flourished in Japan under the name of Zen, and it was introduced to western readers through the writings of Daisetsu Suzuki. The other schools are mainly of interest to historians and philosophers.

The most popular and enduring book which has kept the memory of Xuanzang alive for more than a millennium has been one that would have amazed the real Xuanzang. He has become one of the major figures in a novel, translated into the languages of the modern world and modified according to the tastes of the modern world, the other main characters of which were a monkey and a pig. But knowing about transformations and reincarnations, he might well have been quietly pleased that his mission to bring the true scriptures to the world outside India might still be continuing in a new form.

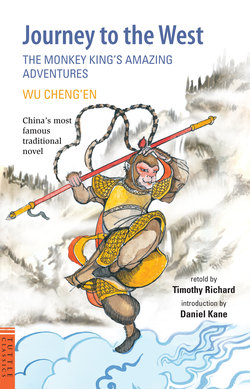

(2) THE JOURNEY TO THE WEST

The novel is a fictionalized account of the legends that had grown up around Xuanzang’s travels. The Record of the Western Regions and The Life of Xuanzang, a biography of Xuanzang written by a disciple, Huili, were full of stories of strange kingdoms with even stranger customs, attacks from robbers and pirates, mountains, ravines, wild animals, and dangers of all types. Even demons and devils are mentioned. Stories about Xuanzang were told by itinerant storytellers in the market places, mixed with various local folk tales and other traditions. Modified history was the stock in trade of the storytellers, other famous stories deriving from the complex history of China during the Three Kingdoms, after the fall of the Han, or the adventures of a group of outlaws living on a mountain during the Song dynasty. Historical details were not important to the storytellers, but the stories were fleshed out with all sorts of fictional embellishments to attract the interest of the listener, or later the reader. Each “round” would end on a dramatic note, with the words “If you want to know what happened next, you must listen to the next chapter.” So the next chapter would start with a brief synopsis of the story so far, before continuing it. This is the origin of the “episodic novel,” the usual form of traditional Chinese novels.

The medieval Chinese mind took it for granted that the area to the west, beyond China’s borders, was full of demons, monsters, and barbarians of every type. The earliest written version of these stories about Xuanzang himself is The Tale of the Search for the True Scriptures of Sanzang of the Great Tang Dynasty, and dates from the Southern Song, but a fragment about the Tang emperor going to hell was discovered in the Dunhuang secret library. In the Southern Song version the Monkey is already Xuanzang’s chief disciple, and their encounters involve gods, demons, and bizarre kingdoms. These stories, and others, continued to accrue and develop in various forms, mixed with local folklore and popular religion, and were collected and edited in their present form in the late Ming. The entire book is very long, and the plots and sub-plots, with their myriads of demons and other strange creatures, make very demanding reading. At much the same time abridgements were produced, about a quarter of the length of the original. During the Qing the book was usually read in abridged form, and one such edition formed the basis of the present translation.

On one level The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures is an adventure story, and a very funny one. On another level it is an allegory in which the pilgrimage to India is a simile for the individual seeking enlightenment. On the first level, the monkey, the pig, the monk, and the sand spirit, and the innumerable demons and monsters, are characters in an adventure. On the second, they are personifications of our own inner spirits and demons: the pure, idealistic monk trying to achieve spiritual awareness, trying to keep the impetuous monkey, the lazy and lustful pig, and the mournful but reliable sand spirit under control, while all the time being confronted with internal and external demons which must be conquered to continue the way forward. One yet another level for the specialist the book presents an extraordinary range of religious folklore, both Taoist and Buddhist. There is much discussion about how much of the book is Buddhist, how much Taoist: even how much, if any, Confucianism is in it. Xuanzang was a committed Buddhist, of course, but the general theme of the book seems to be san jiao wei yi “the three religions are really one.” Each deserves to be treated equally: which as far as the Monkey is concerned, is to be treated with equal irreverence. As we shall see, Timothy Richard also saw Christian themes in the novel, an interpretation shared with no one else.

Before the story proper begins, there is a long section which has nothing to do with the monk or his mission, but deals with the exploits of the Stone Monkey, who has learnt an amazing range of skills, including the seventy-two transformations and the secret of immortality, and who claims the title of Great Sage, the Equal of Heaven. His major characteristics are his cheekiness and guts: afraid of no one, irreverent towards everyone, including the Jade Emperor of the Taoists and even Buddha himself, whom he derides as “a perfect fool” until he learns better. He causes havoc in heaven, and eventually the Jade Emperor calls on Buddha’s help. He is then trapped under a mountain for five hundred years.

The introduction is followed by the story of how Guanyin, known throughout the Western world as the Goddess of Mercy, is instructed by Buddha himself to bring the scriptures to save lost souls to China, which in the novel is portrayed as being in desperate need of such guidance (reflecting, by the way, the attitude of the Indian monks to China in The Record of Western Regions). Guanyin gives this task to the monk Xuanzang, and provides him with three protectors, a monkey, a pig, and a sand spirit. Here we learn that the monk had a past life, in which he was the Golden Cicada, a favorite disciple of Buddha, who failed to pay attention during a sermon and was punished by being reincarnated in China. His disciples are not ordinary monkeys or pigs either: they had all formerly been spirits with official positions in the Celestial Palace of the Jade Emperor, but for various reasons offended their rulers and were sent to earth as punishment. Part-human, part-something-else, they seek to regain their previous status, and agreed to help Xuanzang as an atonement for their sins. The monk undertakes this mission for a variety of reasons. One, of course, is to bring enlightenment to the lost souls of China. Another reason is also to fulfill a vow made by Emperor Taizong, who has seen Hell and ransomed himself out on condition that he would establish a Society for the Salvation of Lost Souls. This provides a secular, as well as spiritual, justification for the trials for the journey.

The last three chapters of the novel describe Xuanzang’s entry into Paradise and his return to earth to bring the holy scriptures to China, after which he attains Buddhahood. Between the introductory section and the final conclusion there are 86 chapters. In each of these, the pilgrims are confronted with various demons and monsters, fight with them, defeat them, and continue the journey. Many of the stories extend over several chapters. The geography of The Record of Western Regions is real, including modern Xinjiang, Afghanistan, and India; the geography of the novel is a series of kingdoms of barbarians with strange customs, suspicious temples, and monasteries where danger usually lurks, or mountains and ravines inhabited by demons who live on human flesh. These are usually anxious to eat Xuanzang himself, as his holiness would confer immortality. The demons, too, have previous lives: they are usually animal spirits in semi-human form. Apart from the demons, there are formidable physical trials: raging rivers, burning mountains, a kingdom ruled by amazons, the land of spider spirits and so on. After a pilgrimage said to have taken fourteen years, they arrive at the half-real, half-legendary destination of Vulture Peak, where Xuanzang meets Buddha, and explains his mission. Buddha is gracious but a bit condescending; he tells his assistants to provide the Chinese travelers with some sutras, but they cheat them, giving them blank sheets of paper. The last chapter describes the return journey to China (flying with celestial messengers, not on foot as in the real story) and a final trial, where they almost lose the scriptures in the fictionalized version of the crossing of the Indus. Here the elephant becomes a tortoise, and the river separating India from China becomes the demarcation line between the Land of Bliss in Paradise and the land of unenlightened souls on earth. They stay on earth only for long enough to deliver the scriptures to the Tang emperor, after which they are returned to Paradise and their just rewards.

(3) DRAMATIS PERSONAE

The only characters who appear regularly throughout the book are the monk, the monkey and the pig. The horse, a former dragon who has also fallen from grace, is sometimes considered a fourth disciple but rarely appears. His job is less to defend the Master than to carry him to India, and carry the scriptures back to China. The various demons they meet along the way are dealt with and usually not mentioned again, though there are occasionally some references to earlier adventures. There are also a number of supernatural actors of both Buddhist and Taoist persuasion who get involved in both celestial and earthly matters from time to time. These are:

(1) The Jade Emperor: a Taoist deity, he lives in the Celestial Palace. He is served by a bureaucracy rather like an earthly one, but his ministers are various spirits, stars, and planets.

(2) The Queen of Heaven, the queen of the female immortals. Another inhabitant of the Celestial Palace. Her garden contained the peach of immortality, which bloomed only once in three thousand years. She could confer immortality on her guests at her peach banquets.

(3) The Ancient of Days, an unusual and memorable name for the Patriarch, a disciple of Buddha, but in the novel seems to be in the Taoist camp. A sort of adviser and ambassador at large.

(4) The Minister of Venus and the Minister of Jupiter: personifications of the spirits of these planets. Their role is rather like the ministers in a Chinese traditional bureaucracy.

(5) Yama, the King of Hell; Judge Cui, the Chief Judge of Hell, the Ten Judges of Hell; Guardian King Li and his sons Nezha and Mucha, various Messengers and other servants: other officials in the nether world of folk religion where the doctrines and spirits of Buddhism and Taoism become very blurred.

(6) The Buddha. In the novel he was many names: The Incarnate Model, the Ideal, the Buddha to Come, the Cosmic Buddha, Maitreya, Tatagatha, and many others. The historical Buddha was a real person, referred to in the novel as Shakyamuni. Buddha appears early in the novel to help the Taoist Jade Emperor suppress the Monkey, and reminds him of his rather insignificant place in the grand scheme of things: when the Monkey thinks he can jump as far as the end of the universe, he finds he has not left the palm of the Buddha. This is the theme of one of the most common bronze curios available in the flea markets of modern Beijing. Buddha appears from time to time, but mainly at the end of the novel, where he presents the true scriptures to the monk for the salvation of lost souls in the Middle Kingdom in the East.

(7) Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. Her Chinese name means “She who hears the sounds of misery of the world.” In some ways the architect of the whole enterprise: Guanyin seeks permission from Buddha to bring enlightenment to the people of the East, which coincides with the vow of the Chinese emperor to found a society for the salvation of lost souls. Whenever in trouble he cannot manage, the Monkey appeals to Guanyin, who comes to the rescue. It is in Guanyin’s interests that the mission succeeds, despite finding the tactics of the Monkey and the others a bit distasteful from time to time.

(8) Ananda and Kasyapa: the major disciples of the Buddha, presented in an unflattering light in this novel. They expect to be paid for the scriptures Xuanzang has sacrificed so much to obtain for the benefit of others, and when Monkey threatens to make a fuss, give them scrolls of “wordless sutras”—plain paper. The pilgrims only discover this when they have left, and eventually Buddha’s disciples supply them with written scriptures, on the grounds that their level of enlightenment was not enough to enable them to understand the wordless ones.

(9) The Emperor Taizong. Apart from the monk, the only human and historically real character in the book. The second emperor of the Tang, he is widely considered the greatest emperor in Chinese history. When Xuanzang set off on his journey, there was a ban on all travel to the interior because of the general military chaos of the time, but when Xuanzang returned in 645 his fame had come before him, and he was warmly welcomed by Taizong, in both the novel and in historical fact. Incidentally, the Big Wild Goose Pagoda that we can now visit in Xi’an is not the pagoda built for Xuanzang, in which he translated the scriptures into Chinese. This was made of mud and clay, and decayed within fifty years. The present structure was rebuilt by Empress Wu Zetian (625-705), and has been partially destroyed and repaired several times.

(10) The real Xuanzang is described in his biography written by Huili. The fictional Tang monk is true to the ideals of abstinence, vegetarianism, and refusal to take life, so Guanyin provides him with three powerful disciples who look after the messier side of life for him. In the novel he is typically attacked, either by demons who want to eat him or women who want to seduce him. He cannot defend himself: that is what the disciples are there for. But he is continuously frustrated at the lack of seriousness and dedication of the disciples: the Monkey is violent and rebellious, and quits several times; the Pig is lazy and always in search of food or pretty women. These altercations between the Monk, the Pig, and the Monkey also provide much of the material of the novel that is not dealing with external threats, but internal ones. Xuanzang has a clear and unwavering sense of mission, which provides the novel with a unifying theme.

(11) Sun Wukong. Originally called the Stone Monkey, he becomes the Monkey King, the Seeker of Secrets, the Pilgrim, and Sun Wukong, “Aware of Emptiness.” Born of a rock, he established himself as Monkey King by showing his courage in entering the Waterfall Cave at the Flower and Fruit Mountain, where no other monkey dared to go. After some time he became restless and went in search of adventure. He caused so much trouble in Heaven that the Four Heavenly Kings and Nezha, the son of Guardian King Li, leading an army of a hundred thousand celestial soldiers, tried to defeat him, without success. Fearless and irreverent of everybody, he upset many Taoist and Buddhist deities, so the Jade Emperor sought the help of Buddha. He was imprisoned under a mountain for five hundred years, and only rescued when Xuanzang came by him on his pilgrimage and accepted him as a disciple. The meeting was really arranged by Guanyin, of course. He is always depicted with his staff, named “As You Like It,” which was originally a pillar supporting the Palace of the Dragon King. This staff, together with his devouring of the peaches of immortality and his ordeal in the eight trigram furnace, which gave him a steel hard body and fiery golden eyes, makes Sun Wukong pretty much invincible. He can only be controlled by a cap of spikes placed around his head by Guanyin, which he cannot remove by himself. The mantra that can tighten the spikes around his head is about the only thing Monkey is scared of, and is Xuanzang’s final resort to try to bring his obstreperous disciple to heel.

(12) Zhu Bajie, also known as Zhu the Pig, or Zhu Wuneng “Aware of Ability.” He is usually called Zhu Bajie, the “Eight Prohibitions,” a name given him by Guanyin to remind him of his Buddhist vows, so much in contrast with his natural inclinations. Richard translated the term as the Eight Commandments. Once an immortal who was a commander of 100,000 soldiers of the River of Heaven, he drank too much and attempted to flirt with Chang’e, the moon goddess (or “the fairies”, as Richard translates), resulting in his banishment into the mortal world. He was supposed to be reborn as a human, but ended up in the womb of a sow, and he was born half-man half-pig. In the original Chinese novel, he is often called daizi, meaning “idiot.” His weapon is the “nine-tooth iron rake.” He and the Monkey seem to be constantly engaged in a sort of game of one-upmanship, and this rivalry provides some of the funniest scenes in the novel.

(13) Sha the Monk, or Sha Wujing “Awakened to Purity.” He was exiled to the mortal world and made to look like a monster because he accidentally smashed a crystal goblet at a heavenly banquet. He lives in the River of Quicksand, where he terrorizes travelers trying to cross the river, and occasionally eats them. This is the reason he is often depicted with a necklace of skulls, as in the Japanese television series. He is also persuaded to join the pilgrimage. Like Monkey, who knows 72 transformations, and the Pig, who knows 36, he knows 18. His weapon is the Crescent Moon Shovel, and he is usually depicted with it. Compared with the others he is well behaved, obedient, and reliable, but a bit morose and prone to worrying. At the end of the journey he is made an arhat in Paradise, while the Pig is made Official Altar Cleanser, meaning he gets to eat the offerings on every Buddhist altar throughout the country. It is hard to imagine a more perfect image of Paradise for the Pig than that.

(14) The bodhisattvas were enlightened souls who chose to forego Extinction in order to remain in the world of mortals to use their understanding and wisdom to help other people along the road to enlightenment. The most famous were Avalokitesvara, the Indian prototype of the Chinese Guanyin, and Manjusri, in Chinese Wenshu. Samantabhadra, in Chinese Puxian Pusa, also plays a role in the novel. Pusa is the Chinese form of bodhisattva. The arhats, in Chinese luohan, are disciples of the Buddha who have already attained enlightenment. They have no role to play, but are often mentioned in the context of the inhabitants of the Buddhist Paradise. There are also a variety of messengers, which Richard calls angels, or occasionally seraphim and cherubim, who have minor roles. Other spirits have delightful names such as The Divine Kinsman and the Barefoot Taoist. Demons are sometimes fallen angels or spirits, or in the allegorical sense, the more evil aspects of human nature.

(4) RICHARD’S TRANSLATION

The first English translations of the Record of Western Regions and Huili’s Biography of Xuanzang were by Samuel Beal, Records of the Western World, London, 1906, and The Life of Hiuen-tsang, London 1911. Timothy Richard published his translation of The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures in 1913. His title and subtitle shows his understanding of the book: “ A Journey to Heaven, being a Chinese Epic and Allegory dealing with the Origin of the Universe, The Evolution of Monkey to Man, The Evolution of Man to the Immortal, and Revealing the Religion, Science, and Magic, which moulded the Life of the Central Ages of Central Asia, and which underlie the Civilization of the Far East to this Day. By Ch’iu Chang-ch’un. A.D. 1208-1288 Born 67 years before Dante.”

One can scarcely believe this is the same book that Arthur Waley called Monkey, or the basis of the TV series Monkey Magic and the many other adaptations since. But it is, and it is important to understand why. Confucian China, like Victorian England, was a rather moralistic society. Confucian scholars considered novels frivolous, but like their Victorian counterparts, were not adverse to a bit of nonsense every now and then. Nevertheless, all literature, even the most frivolous, had to contain a moral message. This was the intellectual environment Richard was living in.

To Richard, the moral message of The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures was clearly that of the pilgrim struggling against internal and external demons towards enlightenment. Richard was a Baptist missionary, born in 1845 and first assigned to Yantai, in Shandong. He became the editor of the Wanguo Gongbao, known in English as A Review of the Times, a reformist journal founded by the American Methodist missionary Young J. Allen. Its subject matter ranged from discussions on the politics of Western nation states to the virtues and advantages of Christianity. It attracted a wide and influential Chinese readership throughout its thirty-nine year run from 1868 to 1907. The Qing reformer Kang Youwei said of the publication: “I owe my conversion to reform chiefly on the writings of two missionaries, the Rev. Timothy Richard and the Rev. Dr. Young J. Allen.” Kang Youwei and his student Liang Qichao are generally regarded as the most important reformers in late Qing China. Richard was a prolific writer and translator, and one of the most influential missionaries of his day, often ranked with and compared to Hudson Taylor, the founder of the China Inland Mission.

Although a committed Christian missionary, Richard was fundamentally an internationalist, and fervently believed in the cause of modernization. He did not share the general view of the missionaries that Christianity was the only revealed Truth from God; rather, he argued, Christianity and the major Chinese religions, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, had much in common. Some of these communalities were superficial, like vestments and rituals; others were deeper, including the urge to seek spiritual enlightenment and the belief in a Higher Power, known by different names in different religions, but essentially the same. Richard did not insist that converts burn their tablets to their ancestors: one could be a good Christian and show respect to ones’ ancestors, with the appropriate rites, without any conflict. This showed an attitude similar to that of Matteo Ricci in the Ming, but differed from most of the missionaries of his day.

The Wanguo Gongbao was extremely influential amongst the Chinese educated classes, and Richard mixed with high officials easily. Clearly he knew Chinese very well, and was well versed in Chinese literature and history, which would have made him even more respected by the Chinese literati. Despite the anti-Christian Boxer Rebellion, during which many thousands of Christians had been murdered, he believed that the Chinese educated classes were not fundamentally opposed to the West, or to scientific progress, or to Christianity itself. So he must have been delighted to discover The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures. Many of its themes resonated with his own intuitions: the Three Religions are One, and respect is due to all of them. To this Richard offered his own insight: moreover, many of the characteristics of the Chinese religions, Mahayana Buddhism in particular, are shared with Christianity. Richard thought he had discovered the connection in The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures. The other issue Richard was passionate about was that scientific thought was not foreign to the Chinese tradition; was that there was a tradition of scientific knowledge in China, and the evidence was in The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures.

Richard’s attitudes are reflected in both his translation and in his notes. He often translates the Jade Emperor as God, the Taoist Celestial Palace and the Buddhist Paradise as Heaven and Maitreya, the Buddha-to-Come, as the Messiah. Messengers are angels, Taoist immortals and Buddhist bodhisattvas are all saints, and the Buddhist/Taoist paradise is populated with such Old Testament figures as cherubim and seraphim. That the Jade Emperor in his Celestial Palace could see what was going on below proved to Richard that “the telescope was invented by Galileo only in 1609 AD, therefore the Chinese must have had some kind of telescope before we in Europe had it.” When the Monkey is showing off his knowledge of Buddhist metaphysics and getting it all garbled, he says “the fundamental laws are like the aiding forces of God passing between heaven and earth without interruption, traversing 18,000 li in one flash.” To which Richard added a note: “The speed of electricity anticipated.”

The last chapter of Richard’s translation even has the Buddha berating Xuanzang for not believing in the “true religion,” which Richard claims was Nestorianism, a variety of Christianity that flourished during the Tang. And among the many Buddhas and bodhisattvas in the final litany, Richard managed to insert a reference to Mahomet of the Great Sea, to the Messiah and to Brahma the Creator. The reference to the Messiah is Richard’s translation of Maitreya, the Buddha-to-Come; the reference to Brahma is his translation of the Narayana Buddha. How Richard got “Mohammed of the Great Sea” out of Chingjing dahai zhong pusa, “The Bodhisattvas of the Ocean of Purity” is a bit of a mystery. He may have misunderstood chingjing “pure and clean” as qingzhen “pure and true,” the Chinese term for Islam. People see things the way they want to see them, and Richard’s fundamental approach was that he wanted to see references to God, Jesus, the Messiah, and even Mahomet and Brahma, whether they were there or not.

This was not entirely fantasy. The Nestorian Stele was a Tang Chinese stele discovered in 1625, which proved the existence of Christian communities in Chang’an during the Tang dynasty, and revealed that the church had initially received recognition by the Tang Emperor Taizong in 635. Taizong, of course, was the emperor who welcomed Xuanzang back to China and had the Big Wild Goose Pagoda built to house his scriptures. But any connection between Nestorian teachings and The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures has never been made by anyone else.

All of this strikes the modern reader as bizarre. Richard’s claims that he had discovered that Mahayana Buddhism was somehow much the same as Nestorian Christianity and that the author of The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures was a closet Christian, attracted a good deal of criticism from less eccentric missionaries, in particular Bishop Moule. Richard later translated Ashvagosha’s Dacheng Qixinlun (The Mahayana Tradition on the Awakening of the Faith), further exploring his theories that Mahayana Buddhism was consonant with Christian teaching, and that recognition of this would lead to more rapid evangelization of the millions of Buddhists in China. Despite much public criticism, he persisted in this line of thought till the end of his life. His open approach to religious matters led to unexpected results. Kang Youwei, who acknowledged Richard’s influence on his thinking, dedicated himself in the later years of his life to the writing of The Book of Grand Unity, which curiously reflected many of Richard’s ideas: a world ruled by one central government, and the improvement of humanity through the spread of modern technology.

These comments are by no means meant to belittle Timothy Richard. Along with Hudson Taylor, he is regarded as one of the most influential and prolific missionaries of the non-conformist Christian tradition in China. Richard was closely involved with famine relief in North China as early as the 1870s. During the Boxer Rebellion (1900) some two hundred missionaries and their families were massacred in Shanxi. When the question of reparations was raised, the Prime Minister, Li Hongzhang, asked Richard for his advice. Richard suggested an indemnity of $500,000 be spent on establishing the Taiyuan University College (later Taiyuan University, now Taiyuan University of Technology). Richard was its Chancellor and Moir Duncan its first Principal. The Chinese government also instructed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to consult with Richard and the Catholic Bishop of Peking on the improvement of relations between the government and the missionaries. Both men were awarded the title of First Grade Officials of the Qing Empire.

Though essentially forgotten because the things he found important and the intricacies of the political situation in China in which he was involved are now history, and rather obscure history at that, that does not diminish his status in the eyes of specialists in the history of the Christian missions in China. His heart was in the right place. It may well be that his translation of The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures might well be the work for which he is most remembered so many decades after his death.

(5) LATER TRANSLATIONS AND ADAPTATIONS

Times change, and the missionary zeal of the nineteenth century missionaries is very foreign to the moder n reader, just as the preoccupations of late Qing China are foreign to modern Chinese. When the book was written, or compiled, novels were not taken particularly seriously. The question of authorship was not important. It was regularly ascribed to Qiu Changchun, a Taoist in the entourage of Chenghis Khan, who had also written a book with a similar title about his travels in Central Asia. Qing commentators stressed that the book had a “deeper meaning” than an adventure story about a monkey and a pig, a view reflected in Richard’s introduction: “Those who read the adventures in the book without seeing the moral purpose of each miss the chief purpose of the book. Those who may be disposed to criticize the imperfect character of the converted pilgrims, must remember that their character is in the process of being perfected by the varied discipline of life.”

The twentieth century saw the fall of imperial China and the disintegration of traditional culture. The New Thought Movement, following the May Fourth Movement of 1919, had a number of issues on its agenda, one of which was the creation of a new literary language based on the spoken language, rather than the language of the classics two thousand years earlier. Another important issue, in the words of its main spokesman, Hu Shi, was “the re-evaluation of all values.” And so The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures becomes one of the central texts of the vernacular language movement, because it was indeed written in vernacular Chinese, and was indeed popular. Literary scholars came to the conclusion that its compiler was one Wu Cheng’en, and Wu’s name is routinely given as its author. Modern specialists feel the evidence for this attribution is too weak: in Anthony Yu’s full and scholarly translation of the novel, the name of the author is simply omitted. As part of the rationalism of the New Culture Movement, the “hidden message” of the book was re-examined and found to be irrelevant, or non-existent. So Hu Shi, in his Preface to Arthur Waley’s translation, wrote, “Freed from all kinds of allegorical interpretations by Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucianist commentators… Monkey is simply a book of good humor, profound nonsense, good-natured satire, and delightful entertainment.” That is an early twentieth century assessment, and has influenced the way succeeding generations have read the story.

The original book is very long. William Jenner’s complete translation runs to 1410 pages; Arthur Waley’s translation has 314 pages. The first seven chapters of the novel deal with the Monkey’s adventures in heaven, before he becomes a disciple of Xuanzang. These contain many of the most famous stories in the book, and both Richard and Waley include them. The next chapters, with the exception of a sort of interlude in which the disciples are recruited by Guanyin to escort Xuanzang to India, are mainly concerned with their travels, encounters with various demons and other strange inhabitants of the western regions. In the last chapter Xuanzang reaches Vulture Peak, brings the sacred scriptures to China, and returns to Paradise, where he too attains Buddhahood.

The central part of the book covers the adventures of the pilgrims; each translator makes his own choice of adventures to include. Richard chose to translate the first seven chapters, the last three chapters and the chapter on hell in some detail. Waley translated about one third of the book, mainly about the Monkey, but not neglecting the Buddhist aspect of the novel. He translated most of the dialogue, but not the poetry, which, as he said “does not go well into English.” Richard included all the chapters, as did the Chinese abridgements from which he was working. He translated the poetry but the dialogue and much of the descriptive passages were shortened and simplified. Some were summarised so drastically they become incoherent: they are little more than “monkey meets demon, monkey fights demon, monkey defeats demon.” In his translations of the poetry, Richard conveys a sort of profundity within abstruseness which contributes to the particular charm of this translation. The last two chapters, the Shedding of the Mortal Body and The Mission Achieved, are the summary and real meaning of the whole book to Richard, which are very moving. The novel ends with a litany of the Names of the Buddha and in homage of all the other bodhisattvas and arhats of heaven.

The earlier stage versions of various stories in the book in local opera form were incorporated into the much more elaborate and elite Peking Opera repertoire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. These also made the Monkey the central character. The role of Monkey was played by many famous actors, included the father and son Yang Yuelou (1844-1889) and Yang Xiaolou (1878-1938); and later by Li Shaochun, Li Wanchun, and Ye Shenzhang. During the late 1930s and early 1940s The Monkey King was so popular in Beijing that it was performed in several theatres simultaneously. The image of the Monkey they created is now very famous: standing on one leg, the other crossed over his knee, his hand covering his eyes as he peers into the darkness looking for demons, his eyes twitching nervously, holding his staff, and of course his chatter and his acrobatics.

In 1964 the Monkey King story was transformed into two animated cartoons produced in China, both about the Monkey with no reference to the Monk. These cartoons, Monkey Causes Havoc in Heaven and Monkey Upsets the Peach Banquet, featured Monkey as a sort of Mickey Mouse figure modelled on the Peking Opera version. There have been many other cartoon versions of the Monkey King, but the popular consensus is that none have surpassed the 1964 animations. After the Cultural Revolution the most widespread depiction of the Monkey on the stage was Monkey Beats the White Bone Demon, a modern allegory on Deng Xiaoping outwitting Jiang Qing, the widow of Chairman Mao and one of the so-called Gang of Four.

Outside China, the most significant development in the Monkey myth came during the 1960s with the Japanese series Monkey Magic. This was truly weird, with a middle aged woman playing Buddha, and a beautiful young actress, Matsuko Natsume, playing the young monk. Thirty odd episodes were produced, with little reference to the original book. It was based on the original characters, of course, and brought out their characteristics very well: the monk with a mission, the restless, rebellious monkey, the easy going, gluttonous, lustful pig, and the mournful, pessimistic sand spirit. One of the many interpretations of the book is that the many arguments and disputes between these four are in fact an inner dialogue, as we all wrestle with the rebellious, restless, gluttonous, lustful, mournful, and pessimistic personal demons, all of which are somehow kept in check by the higher aspirations of the soul. Freud would have said something about id, ego, and super-ego. This can easily be read into the pseudo-mystical comments threaded through Monkey Magic. The dialogue was dubbed by the BBC in a faux Japanese accent. It became somewhat of a cult, and still has many adherents. A sad postscript is that Matsuko Natsume, who was twenty-one when the series was made, and whose character is constantly reflecting on the transitory nature of life, died of leukaemia at the age of twenty-seven.

Since then there have been musicals, children’s theatre versions, a full and serious version produced in China (which stays close to the original book), innumerable manga adaptations, video games, and a number of movies and TV series, mainly from Hong Kong. Each of these reflected the tastes of the day. If Richard’s translation reflects the general cultural milieu of the late nineteenth century, both in China and Victorian England, and if Waley’s translation reflects the taste of the urbane British reader of the thirties, we can say that the Japanese series reflects the good humored innocence of the 1960s and the various manga, TV, and film versions of the late twentieth century reflect the technology, and in many cases the taste for violence, of that time.

The latest adaptation is The Forbidden Kingdom, which comes at a time when Chinese gongfu movies have now become part of Western popular culture, thanks to the pioneering work of Bruce Lee; when Chinese movies of a mystical turn are well known because of A Touch of Zen and the like, and when traditional wuxia (knight errant) and gongfu (martial arts, with a touch of magic) stories like Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon have made this aspect of Chinese culture well known in the West. Outside the Chinese cultural sphere, The Lord of the Rings was one of the most popular works of literature of the late twentieth century, and the movie version of the early twenty-first century made it part of the consciousness of the general movie fan, whether they had read the book or not. The idea of the quest through dangerous lands full of demons and ogres, of friendly and unfriendly kingdoms, of determination, fear, courage, and the rest has become a resonant theme in Western culture. It is almost as if the traditional interpretation of The Journey to the West is reflected in the mood of the early twentieth-first century, in a new idiom.

Timothy Richard was famous in his day, but has been more or less forgotten by the currents of history. His translation, made with such hopes, may never have had much of a circulation, and was superseded by that of Arthur Waley and more recently by the full translations of Jenner and Yu. In this re-edition of Richard’s translation, some of the shorter chapters have been omitted, and many of them have been linked together in what is more or less a coherent sequence of events. Some of the more far fetched translations and comments have been excised, but the general flavor of Richard’s translation remains more or less intact. We do not know the process by which Richard made his translation, but I strongly suspect a Chinese colleague read it to him, explaining and commenting along the way, and Richard took it down quickly in English, which he later revised. It cannot really be considered a translation in the modern sense of the word. Anthony Yu, in his preface to his full and scholarly translation of The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures, comments, “Two early versions in English (Timothy Richard, A Mission to Heaven, 1913, and Helen M. Hayes, The Buddhist’s Pilgrim’s Progress, 1930) were no more than brief paraphrases and adaptations.” But few people have the time or energy to wade through 1340 pages, unless they are students of Chinese literature and use the translations as a crib to read the original.

Richard’s translation is much more than a brief paraphrase: it is a very readable version and is quite close to the original, though often in an abbreviated and summarised form. It has its quaint and quirky side, but that adds to its charm. It is an auspicious time to rescue it from oblivion and re-issue it for another lease of life. The passage of Xuanzang’s story has indeed gone through seventy-two transformations. It has acquired monkeys and pigs, has been reinterpreted in Peking Opera, in musicals, in movies, in manga, and most recently as a martial arts epic. Somewhere in this series lies the translation by Timothy Richard. Both Xuanzang and Richard would be amazed, but pleased, to see that the transformations continue while the essence remains.

Daniel Kane

Professor of Chinese at Macquarie

University, Sydney