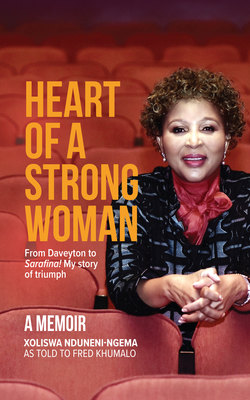

Читать книгу Heart of a Strong Woman - Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеShell-shocked

I was not there to witness the excitement of the wedding ceremony. Even though I was in Johannesburg that day, almost 600 kilometres from the action, I was singed by the fire that was burning down there in Durban. I knew that what happened in that church was to change my life forever. It had to change because the man getting married, Mbongeni Ngema, was at that time still my lawfully wedded husband. I was the mystery woman whose name got tongues wagging and tempers rising. I was, and still am, Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema. I was not about to let Mbongeni get away with it just like that. I wanted him to be accountable. If he wanted to marry another woman, fine, but he had to do it the proper way. That was why I stopped that wedding. I was not being melodramatic or attention-seeking. I had to fight.

But of course, that is not how you start a story. First of all, it has to be clear that this book is not only about my marriage to Mbongeni Ngema. It is also about the birth and triumph of Sarafina!, the production we birthed together; the production that changed the face of South African theatre; the production that gave impetus to the careers of many artists – actors and musicians – who will continue to be reference points in cultural production in this country. This book is about how theatre can actually make a people.

However, in telling the story of Sarafina! it’s inevitable that the narrative includes the personal. Had I not met Mbongeni Ngema, Sarafina! probably wouldn’t have happened. Or it wouldn’t have taken the character it did at the end. Because Mbongeni and I fed into each other. He was, and still is, a great artist; but every artist needs a muse. I was that muse. But also more. I was the person looking at the finances. I was the one acting as mother, sociologist, sister and teacher to members of the cast who came to us at ages as young as fifteen – staying with us for months, years, before they went back to see their biological parents. So, you can already see that ours was not a conventional approach to theatre. We looked after the actors and actresses beyond the lights and glamour of the stage. Which is to say, at the core of this book is the confluence of our artistic and personal lives; how one fed the other, how they bled into each other. Art cannot happen in a vacuum. Art is a human endeavour. Or rather it is an attempt to probe the meaning of life, what it means to be human. All of this informed my decision to start this story with a human drama, one that has remained embedded in the minds of many and which gets invoked whenever and wherever my name gets mentioned.

But to answer the question ‘Who is this Xoliswa?’, we have to go back to the past, to the township of Daveyton, on the East Rand, where I was born in July 1962.

Daveyton, like most black townships in South Africa, was created as a labour reservoir to serve white people in neighbouring towns such as Benoni and Boksburg. In the case of Daveyton, the black people who settled there came from all corners of the country – and beyond – looking for work in the City of Gold and its environs. The mines in Benoni and surrounding areas on the East Rand were the impetus for this migration. Once the towns had been established around the mines, other kinds of industries, textiles, for example, soon mushroomed. While the men worked on the mines, the women served the factories. Many women also worked as domestic servants for white families.

Like so many others, my parents came to Johannesburg lured by promises and hopes of work and an easier life. My father came from the Ciskei, ku Qoboqobo near Alice, and my mother from Graaff-Reinet, both in the Eastern Cape. After moving around different parts of the Greater Johannesburg area, they settled in Daveyton, where I was born on 21 July 1962. My parents were what we would call working class, in that my father was a labourer and my mother a domestic worker and, later on, factory workers. We were no different from the bulk of our neighbours.

Like many townships, Daveyton had sections segregated along tribal lines, in keeping with the grander scheme of apartheid whose motto was ‘separate development’. Naturally, I grew up in the Xhosa section of the township. It’s tragic what the apartheid architects did. As a result of those divisions, a measure of resentment for those outside our tribal circle set in. It was not uncommon for a person to be beaten brutally – sometimes killed – for having strayed into the ‘wrong’ section.

However, with increased politicisation, the racial stratification backfired on the apartheid architects as our people soon realised how interdependent they were. The Bhaca and Zulu people were generally highly regarded when it came to manual work, fixing things, and their skills came in handy across tribal lines.

Over and above the commercial aspects of people’s relationships, culture became a catalyst for a conversation which defied the imposed tribal boundaries. One of the most famous musicians from Daveyton was Victor Ndlazilwana. The multi-instrumentalist and singer came from our section of the township. He was Xhosa. I must admit that I was too young to have been au fait with the kind of music he played, but I knew he was highly regarded not only in the township but all over the country because his music was played on radio. It also helped that his daughter Nomvula was my classmate at Ntsikana Primary School. Even at the age of thirteen, she was already playing in her father’s band, which travelled all over the country. I have seen a picture of her playing the piano to excited crowds in the United States, at the tender age of thirteen.

Although Ndlazilwana was, as I have said, of Xhosa stock, in his musical journey he inevitably worked with people from across the tribal divide. As a result, in his band the famous Jazz Ministers he had the likes of trumpeter Johnny Mekoa, who was Sotho speaking, Boy Ngwenya, who was Zulu, and so on. Apart from formal bands like the Jazz Ministers, the township thrummed to the sounds of music from different parts of the South African cultural melting pot. This was especially so over the weekend. You’d be on your way to church and you’d come across a group of Zulu men, sometimes dressed in the complete traditional regalia of amabheshu and imbadada, and they would suddenly be dancing for your own personal pleasure. Somewhere down the road Basotho men in their ubiquitous blankets and conical hats would be shimmying to the music of the concertina.

Music was a way of life. It was central to black life. Funerals could not be conducted without there being music at the centre. Weddings, traditional feasts and ordinary parties offered people an outlet for the frustrations born of their bleak daily existence – frustrations which they channelled through music. Even the chain gangs who fixed our roads did everything to the thud and beat of music. You would see them lined up on the side of the road, their picks and shovels making love to the stubborn earth. With every thrust of a sharpened pick into the ground they would grunt rhythmically: ‘Abelungu oswayini! Basincish’itiye basibize ngoJim.’ (Whites are swine; they deny us tea, and call us Jim.) The white overseer would be standing not far from these men, smoking his pipe or drinking something from his flask, oblivious to what was being said about him and his fellow whites.

Music. Everywhere you went there was music. When I began to be conversant with the different musical traditions I couldn’t help noticing that the name of Ndlazilwana was mentioned constantly; and wherever he was mentioned, the name of King Kong, a musical stage play, was also mentioned. Ndlazilwana had been part of the cast of King Kong that travelled to the United Kingdom in 1959. However, unlike most members of the cast – including Hugh Masekela, Miriam Makeba and Jonas Gwangwa – who stayed on in the UK after the production ended, Ndlazilwana came back to South Africa. He immediately got busy setting up new bands, resuscitating the African-jazz tradition in South Africa.

While the King Kong cast were busy wowing audiences in the UK in 1959 up to 1960, after which many of them started their own individual careers – some of them became legends – back home the music never stopped. But more importantly, a local man, who, ironically, had helped discover many musicians while he worked for Gallo Africa as a talent scout, was busy carving himself a career as a writer of musicals in the tradition of King Kong. That man’s name was Gibson Kente. By 1971, when I around nine years old, Kente had become such an influence in local theatre that everyone who was interested in acting sought him out. Those who thought they were playwrights were producing what were then called ‘sketches’, which, as would later be discovered, were actually what we would today call cut-and-paste jobs of Kente’s productions.

Very young as I was, my parents allowed me to join the local drama society. They were generally protective, and dismissive of those who thought they could make a living through the arts. ‘I don’t mind when you sing over the weekend, or at church, but don’t tell me you think singing or acting in those stupid sketches is a real job’ was how my mother would respond whenever any of us children excitedly announced that we wanted to get involved in the arts. The only reason my parents allowed me to join the dramatic society was because my brother had joined; it was something he did over the weekend.

The dramatic society grew very fast. In no time at all it was staging productions at the local community hall, attracting huge paying crowds. My brother was hired as a doorman – he collected gate takings. Even though they still hadn’t featured me in any of the productions, I had become an appurtenance, an inevitable presence at the performances. I watched grown-up actors and actresses, and aped their movements and recited their lines. I also sang. In the Gibson Kente tradition you cannot act if you can’t sing. I assigned myself parts which I rehearsed religiously. I made it a point that the director and also my brother, who was close to the director, could see I had the resources. So, eventually, this ten-year-old was given a part.

On the day of the performance the Tsakene Hall in Brakpan was packed. Together with the other cast members, I sat backstage while the director tried to get the excited crowd to quieten down so that the performance could begin. Finally, he succeeded and the first act started – a group which exploded into a music and dance act. Then came my scene. I was gently guided towards the stage. I emerged from behind the curtain, ready for my moment. But when I saw the sea of faces, and heard the whispers, and smelled the sweat of the crowd, I froze. All of a sudden I didn’t know what I was doing there. Tears started falling down my face. I think I heard some people giggling; others went Shhhhhh! I ran backstage without uttering a word. The director tried to cajole me into going back to deliver my lines. No, nothing doing!

That was the end of my acting career, over before it started. It didn’t end my love of the theatre, though, and it was the director himself who saw a new role for me. ‘Xoli, you’re smart,’ he said, ‘and quick with figures. Maybe you should take over from your brother in managing the box office.’ And so I became the money person for the dramatic society. As a doorwoman, I was strict: no money, no entrance, no discount. Unbeknown to me, I was laying the foundations for a highly successful career as a manager in the theatrical world.

*

Over the years I have watched hundreds of theatrical productions locally and internationally. Some of them have been excellent, others mildly successful, while the bulk were trashy. It takes a lot to write and produce a play. It takes even more work and guts if you get into the industry with very little training, and absolutely no money, and still hope to pull off a successful production.

Towards the end of 1974 something happened in the theatrical world which I think had a slight bearing on a decision by my parents to remove me from my school in Daveyton. That year, Gibson Kente staged a play called I Believe. In the production, Zwelitsha (played by Peter Sepuma) is a rebellious youth leader, constantly fighting the main security cop (played by Darlington Michaels). Zweli has a vision of a violent confrontation between young people and forces of government. The play ends tragically. I guess you can already tell where this is going. Yes, Kente foresaw the student revolution of 16 June 1976. In 1975, the language of tuition of most subjects was changed to Afrikaans, and this caused the 1976 riots.

At the beginning of the 1976 school year my parents took me to Nzimankulu in Queenstown and enrolled me at a junior secondary school there. Although later I would realise that the move to the Transkei was a blessing in disguise, the transition from urban Daveyton to Nzimankulu was a shock and I missed home terribly.

On 16 June 1976 I was at Park Station in Johannesburg, having travelled home from Queenstown for the mid-year holidays. The station was swarming with soldiers and policemen. I couldn’t understand why. But the next day, 17 June, I understood. Daveyton, along with the rest of the East Rand, erupted into violence. There were running battles between township youths and the police. It would go on for quite a while, people dying left, right and centre; children disappearing, some of them fleeing into exile, others dying in police custody and their bodies simply vanishing into thin air. Of course, I did not know all of this at that time; it was something that one would learn about at a later stage – through newspaper reports, word-of-mouth accounts and, much later, books that put the story of 16 June 1976 into its proper context.

At any rate, I stayed in Daveyton for three weeks after the explosion of violence, and then went back to the calm and tranquillity of Transkei. The painful irony was that while many parts of black South Africa were in flames, the homeland of Transkei was loud with song and celebration. Under the leadership of Paramount Chief Kaiser Daliwonga Mathanzima, Transkei had been granted independence from Pretoria. People who lived in Transkei, who, a few weeks before, were fully fledged South African citizens, were suddenly told they no longer belonged to South Africa. They now belonged to the Republic of Transkei, a self-governing state with its own national anthem, its own radio station, its own flag, and its own passport – incwadi yokundwendwela. In other words, if you were travelling from Transkei to South Africa, you needed to produce this passport which proved that you were a citizen of the Republic of South Africa. To make a bizarre scenario even more laughable, the Republic of Transkei even had its own embassy in South Africa.

In preparing this book, I went back and read some of the reviews of Gibson Kente’s many productions and the impact they had on people of my generation. In my search, I was pleasantly surprised to find a biography called Bra Gib: Father of South Africa’s Township Theatre, written by Rolf Solberg. In the book, there’s a reproduction of an interview with Kente, in which he is giving context to his arguably most prophetic play, I Believe: ‘I was saying I believe that if the government can take note of the attitude of the youth, of the simmering impatience of the youth, the anger of the youth – if they can act now we might save ourselves a lot of hardships in the future. And for that play I was called “the Prophet” because of what happened later on – there were these strikes and the kids, and 16th [June 1976] and all that, you know, and they said, “Gibson Kente said it would happen!”’

This was what appealed to me about Kente’s work; about theatre and its role not only in entertaining crowds but in contributing towards nation-building conversations. Even as a kid I thought I wanted to be part of that conversation. Just how I would do this was not at all clear in my mind, but I continued to frequent the theatre. When 1976 finally happened people couldn’t help saying, ‘Wow, Gibson Kente saw this first!’ We simply could not believe the accuracy of his vision. But of course, the extent of the violence, the bloodbath the country became was far more nightmarish than Kente’s play. Mind you, by 1976 Kente had done other productions, including Beyond a Song and Too Late.

The school I attended in the Transkei was an old, run-down boarding school in the village called Qoqodala. It wasn’t what I had expected when the words ‘boarding school’ were first mentioned. I had grown up in a township, where we had running water, a toilet just outside the main house. Schools, shops and even a library were all within walking distance. Also in the neighbourhood that I grew up in, I was surrounded by relatives and friends I’d known from since I was born. Daveyton was home. It was a safe, comfortable place where I felt I belonged. All of a sudden, I was in the Transkei, hundreds of kilometres away. In the village we did not have running water and the river, or stream rather, from which we fetched our water was not clean. You had to sift out the tadpoles before you drank it or used it for cooking. I was not used to that. There was also a shortage of food. When it was available, the food was of a poor quality. The bread we ate always smelled of paraffin. We wondered why – until we discovered that the van that transported food also carried lots of paraffin drums, for the school and neighbouring homesteads. As the lorry rattled along the rutted dirt roads from the town to the village, paraffin would spill out of the drums, soaking our bread. It was horrible.

I wrote numerous letters home, complaining about this sorry state of affairs. Because of the poor quality of water, my body broke out in sores. I had fainting spells and endless nightmares. One of the nightmares, I soon realised, harked back to an incident from my early childhood.

I must have been around four or five years old because we still lived in our house on Shongwe Street, in the Xhosa section of Daveyton, when this incident happened. The family had a cat, but I personally had a very close relationship with this animal. I used to feed it, talk to it and pet it. One day I woke up and realised that the cat had not appeared in the bedroom I slept in as was the norm. I went through all the rooms in the house, calling out the cat’s name. No cat. Finally, I decided to go and look outside. I went around the yard, checking under trees. Finally, I found the cat. It was alive. But its eyes had been gouged out. I screamed and screamed. And I think I fainted. Someone had to kill the poor cat. Now, years later, at the age of thirteen, I was in a strange place called Nzimankulu being haunted by nightmares involving my cat. The fainting spells became more frequent. It was later established that I had actually had a nervous breakdown. I was very unhappy and unhealthy in Nzimankulu, and I said as much in the letters I dispatched on a regular basis to my parents back in Daveyton.

My parents sympathised with me. But they had sent me to the Transkei to protect me from what was about to happen. They didn’t say it in so many words, but my parents had, through intuition perhaps, heeded Kente’s message that something horrible was about to happen in Soweto and other black townships in what was then called the Transvaal (Gauteng province today). It was through radio that I followed the tragedy of 1976 and its aftermath. Then, when the embers of 1976 had long faded, something else happened that would change my life forever.

*

A custom that is religiously observed among Zulus is called ‘ukweshela’. Ukweshela is the process whereby a Zulu man encounters a complete stranger and professes his love for her; and he asks the stranger to reciprocate. I know it exists in many parts of Africa, under different names. I know you are wondering how can you profess love to a stranger. Well, the people in Europe call it ‘love at first sight’. Italians, according to Mario Puzo in The Godfather, have another term for it – the ‘lightning strike’. This is because when this thing strikes you, this bolt of realisation that you have these feelings for a person, it hits you with such force that you can’t help but do something about it. You see now, the African man is not a brute by stopping a woman in the street and proceeding to profess undying love to her. The African man is in tune with the mores of civilisation!

At any rate, to continue with the story …

By 1979 I had transferred from that horrible, horrible boarding school in Nzimankulu to St John’s College in Mthatha, Transkei. St John’s College was a real boarding school as I’d imagined it. In fact, it surpassed my expectations. The dormitories were splendid and the entire school equipped with modern amenities. The school attracted children from all over the country, the offspring of the crème de la crème of black society, some of whose parents were academics with multiple degrees, top businessmen, and high-ranking officials in the newly independent homeland of Transkei.

Academically, I triumphed. My health improved. My love for the theatre had not diminished and I joined the school’s drama society. I’d long realised that I would never be an actress, but I knew I could be a useful cog in the big wheel of theatre. I became the drama society’s treasurer and I was also charged with the responsibility of organising theatrical performances. Whenever there was a play in town, I was one of the first to know. I would then approach the authorities for school trips to be organised to local halls. There were no theatres. It was in this context then, when I saw banners advertising the arrival of Gibson Kente’s show Mama and the Load, that my schoolmates and I went to the boarding mistress to ask for permission to go and see the play. It was being performed at one of the local halls. Permission was given. We watched the show and enjoyed it, happy to be reunited with ‘home’ – Johannesburg. There’s a gem of a memory that stands out about Mama and the Load. Mary Twala, Somizi Mhlongo’s mother, was in the play. Somizi was maybe three years old. He was mostly backstage, but tjatjarag as he was even back then, he would slip beneath the curtain and make an appearance on stage before being whisked backstage as if this was all part of the act.

After the show there was what young people would today call an after-party. We had been smart to ask for weekend passes, otherwise we would have been in trouble with the authorities at school. At seventeen I was still very young and naive. I was shocked at what I was seeing – members of the Kente cast, both young men and women, were drinking heavily and smoking. One of the actors, Mbongeni Ngema, was making moves on me. Meanwhile, Ngema’s friend, Percy Mtwa, was interested in my older sister, Mpumi. So Mbongeni started ‘shelling’ me. I was not rude to him, but I gently told him I was still too young and not interested in this jolling thing he was proposing. The night ended uneventfully. We went back to Ngangelizwe township, where my sister was staying.

At the end of the year, my sister Mpumi and I asked for permission from our parents not to come home early for the December holidays. They were okay with that, mainly because the political situation was still dicey. Children our age were being detained for this or the other reason. Mpumi and I then visited Grahamstown. It so happened that Mama and the Load was on in Grahamstown at around the same time! So, off we went to the show. Again, we loved it. After the show Percy Mtwa, the guy who had made moves on my sister a few months earlier, started shelling me! And, I kid you not, Mbongeni Ngema, who had expressed undying love to me a few short months before, was singing his poetry to my friend Ntuthu. Smiling and playing along, we listened to them.

In 1980 I was in matric, my final year. Mpumi had left school. I now had no big sister to look after me or, more precisely, no big sister to worry about. I was on my own. Free and independent. It was during my year-end break that I visited home in Daveyton. I was walking down the street one Saturday afternoon when I bumped into him again. Yes, Mbongeni Ngema was walking down my street! Using his charming smile and words, he stopped and asked to have a word me. When he saw that I was in no hurry to abandon him on that street, he started shelling me: if you agree to be mine, I’ll buy you an aeroplane and a train and the whole ocean, if you want … You know the exaggeration of the Zulu men when they are shelling.

It soon dawned on me that the bugger didn’t even recognise me! But it did not really surprise me. He was, after all, a star, who had women falling for him wherever he went. At any rate, I let him go on a bit with his poetry because he was such an entertainer. Having grown up in Daveyton, I was used to being shelled repeatedly by boys. It was a long-established tradition that when a man encountered a girl or a woman, he was obliged to say something complimentary to her. I am even made to believe that Zulu women of earlier generations used to take umbrage when a man passed them without saying a thing. After such an encounter the woman would go and complain to her friends or sisters: ‘Girls, what do you think is wrong with me? Just tell me. Am I too ugly, or is my dress sense a turn-off to men? I mean, here I am walking down the street, and not a single man stops me to say a word or two to me; to engage in verbal sparring with me. What is wrong with me? My dear God! I am like umgodi onganukwa nja!’ A hole which even the dogs shun. Umgodi onganukwa nja. Men, like dogs, are always sniffing at women who are passing by; like dogs sniffing at upturned dustbins and nondescript holes on the side of the road. If a man does not sniff at a woman who is passing by, then there must be something wrong with that woman. Umgodi onganukwa nja. When I first heard that expression, I laughed myself silly, although I shouldn’t have. I can bet you my bitcoin collection the whole concept of umgodi was not dreamed up by some poor woman who felt unloved. It smacks of patriarchy. My sense is that it would have been coined by a man – someone’s father, brother, uncle – whose main aim was to reinforce the notion that women cannot exist independently. They need men for validation. Therefore, if men do not ‘sniff you up’, so to speak, there must be something wrong with you. You are incomplete.

This kind of psychology, if that’s the right word, should have prepared me for what I was to encounter as I entered into womanhood. A phase where I got reminded time and again that without a man, I was not complete. I could not do some things without the approval of a man. I had to keep quiet when a man did something, even if it did not make me happy. He was, after all, a man. He called the shots. I had never heard of the word ‘patriarchy’, nor had I read feminist theory – but I knew I was not the kind of woman who would keep mum or look the other way while a man did things that might at some stage impinge on her own life.

At any rate, that day when I encountered Mbongeni for the third time, I allowed him to continue spouting his poetry, painting this beautiful world that he wanted to share with me. When he was done, I simply said to him, ‘Uyazi ukuthi usungishela okwesibili!’

With not an iota of embarrassment at being told he was shelling me for the second time, he simply said, ‘Sorry, when I shelled you for the first time I was probably drunk. Remember I was a heavy drinker then. I have mended my ways. I have stopped drinking.’

And indeed, as I was to discover, he had stopped drinking. He had also converted to Islam. It did look like he had turned over a new leaf. In due course, once I’d forgiven his bumbling ways of shelling me endlessly, I gave him a chance. Our romance began. He was good to be around. He made me laugh. The laughter made me feel happy, at ease in his presence. He respected me. He loved me. Although I had no experience in the business of falling in love, I thought what I felt for him was love. It did not matter that he was so poor that he had only two pairs of pants (with patches galore) and maybe two or three shirts. He was always neat. It also took me a long time to discover that he did not have a place of his own.

Having come from rural Zululand to join Gibson Kente’s cast, he had stayed at the playwright’s house while he performed in Mama and the Load. The play was on the road when Mbongeni and Percy Mtwa broke away from Kente and took a chance at carving their own niche in the theatrical industry. When I finally ‘gave him the crown’, as we say in the township, Mbongeni was busy rehearsing the play that would become Woza Albert! The two of them stayed at Percy’s brother’s house not far from my parents’ house in Daveyton.

The more I got to know Mbongeni, the more I realised just how different he was from me. My sister Mpumi tried her best to drive a wedge between the two of us. After all, her own relationship with Percy Mtwa had collapsed.

‘These men are just players, Xoli,’ she said. ‘I’m older than you and far more experienced in these matters. Did you see what Percy did to me? The relationship did not go anywhere. And you, being the young, ignorant and naive girl that you are, your day of disappointment is coming. I am asking you to walk away from him while it’s still early. The higher you go in this relationship the harder you will fall.’

My persistence with the relationship with Mbongeni Ngema turned Mpumi against me. We stayed in the same house, yet hardly spoke to each other. It was such a painful experience. I loved and respected Mpumi. She had in the past been my role model. No, I am actually lying. She was to me a sister, a friend, an intellectual sparring partner and a mother. That’s right.

From the time we were small, and I’d just started school, at our home she played the role of mother. My parents would leave home for work at around 5 am. Sometimes, by the time they left for work my mother would have made breakfast, which we would eat before we went to school and the younger children were sent to their place of care. But other times, my mother would leave in a hurry, without having made breakfast. It therefore fell on Mpumi, as the elder sister, to feed me and my younger brothers, wash us and dress us appropriately (if it was winter, she had to make sure we were dressed warmly; if it was summer, we had to wear shorts; etcetera). Having washed and fed us, she would lock the house and walk with me to school, and the younger kids would be dropped at their place of care, Gogo MaMbhele’s house. All of this at the age of nine or ten. She couldn’t have been older than that when I first noticed her performing these chores every weekday.

One day stands out in my mind. In the morning she fed us as usual and got us dressed. Because it had rained hard the previous night, the streets were muddy. The streets in Daveyton were not tarred then. So, in order to protect our two younger siblings, who must have been around three years and five years respectively, Mpumi put them in their twin-cab pram. The pram only came out on special occasions. With the streets so muddy, it only made sense that Mpumi should drive our two younger siblings in a pram. At any rate she locked the house. We got out of the yard, onto the street. Thanks to the rain the previous evening, the roads weren’t as dusty as usual, but there were puddles everywhere and dozens of treacherous potholes into which an unwary foot could sink, with disastrous results.

The distance from home to my school was only about a kilometre and a half, but for a seven-year-old girl that was still a long way to walk unsupervised by an older person. Mpumi was all I had. I walked alongside her as she pushed the twin-cab pram. My siblings were happy to be in their ‘moto!’ The idea was to first drop the smaller kids at Gogo MaMbhele’s, after which Mpumi and I would proceed to our own school. When we came across a car, Mpumi had to steer the pram onto the side of the road. The car passed. Then she tried to push the pram back onto the road, which was smoother, but the pram was now stuck in the mud. She tried to push. The pram wouldn’t budge. I added my own seven-year-old hands and together we pushed. Nothing doing. The pram wouldn’t move. My younger siblings in the pram did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. They thought we were playing a game. They were giggling, as kids would do. We were going to be late for school, Mpumi said under her breath. She suggested I carry on walking on my own. Once she got the pram going, she would drop the kids at Gogo MaMbhele’s, then catch up with me. I decided to stay with her. We tried pushing again. Still no luck. People were passing by. In their haste to get to work or school they did not pause to look at us, to consider what we were up to. Maybe they thought we were playing. Nor did we stop any of the passing adults to come and help us. At any rate, after a long while two men who were passing by paused long enough to realise that we needed help. They easily and quickly pulled the pram from the mud and set it back onto safe ground. When one of the men offered to take us to Gogo MaMbhele’s, my sister reassured him that it was not very far. We would manage. We did manage. But by the time we got to school, we were splattered in mud. It was not funny.

Then there was another time when Mpumi was supposed to miss school and stay at home because there was a crisis at home. The neighbourhood woman who looked after yet another one of our siblings, who was too small, was not available. Mpumi decided she was not going to miss school. So what did she do? Dressed in her uniform, she tied the little kid to her back as old women do. Then she walked to school. The teachers rushed to her, asking, ‘Why have you brought this child to school?’

She explained her predicament: she could have stayed home and looked after the baby, but then she would have missed out on school. One of the teachers suddenly remembered that that day was prize-giving day, or some such. Mpumi knew she was going to be on the list of prize winners. No snotty-nosed sibling was going to stand between her and her special day. You can readily see that the whole notion of child-headed households did not come with the advent of AIDS, which robbed children of their parents, leaving kids to fend for themselves. In many working-class neighbourhoods in South Africa – especially in the black community, although it was also a reality in the coloured community – child-headed families existed long before social scientists even dreamed up the concept that would dominate social discourse in later years.

Anyway, my sister Mpumi had every right to be angry when I defied her and started having a relationship with Mbongeni. She was more like a mother to me. She knew me better than my mother knew me. She had protected me from many storms in life – in the township when we were growing up, and in the Transkei when we were in boarding school. It was through her that I first met Mbongeni when the Gibson Kente cast came to Mthatha. Now I was defying her.

I will not lie to you, my reader: there were moments of doubt; moments when I thought my sister was telling the truth. I recalled that this man I was head over heels in love with had proposed to me twice before – each time mistaking me for a girl he’d never met. He was a player, indeed! But my inner voice said he had changed. Hadn’t he, after all, stopped drinking and smoking? Hadn’t he converted to Islam, which made him more focused and single-minded in what he wanted in life?

Apart from the fact that he was a smooth-talking player, another reality I couldn’t run away from was that the two of us were an odd couple, with almost nothing in common. He was Zulu, I was Xhosa. He was deeply rural, and I, on the other hand, was a city girl through and through. Until I went to boarding school in Transkei in 1976, I had never been to a place where they collected water from the river, where they used wet cow dung to polish their floors, where womenfolk crawled on all fours whenever they had to serve food to their menfolk. Mbongeni came from a polygamous family – his father had two wives – and in the compound in which he’d lived as a young man, he’d told me, he’d shared food and sleeping quarters with countless aunts and their offspring. I came from a close-knit family – one mother, one father and seven siblings. When my father came to the Transvaal as a young man, he’d cut ties with members of his extended family. As a result, we hardly knew our relatives. We would see them at extremely important family gatherings such as funerals and other traditional feasts, but that was all.

As if that were not enough, it occurred to me that I was far more educated than Mbongeni; I had finished matric at an exclusive boarding school and he hadn’t even finished high school. That did not stop him from being egotistical, patriarchal and talkative. Initially I thought that in his display of over-confidence he was compensating for his lack of schooling, but in due course I realised that, though he valued education, he did not feel inadequate in my presence. In fact, he wanted to embrace my academic achievements and draw inspiration from them. A voracious reader, he would sit me down and share with me writings by authors I’d never heard of. Everyone from Frantz Fanon to Peter Brook to Jerzy Grotowski.

Considering the fact that I’d been the one who’d spent three years at the prestigious St John’s College, where I’d just finished high school the previous year (1980), I should have been the one leading him to fresh and deep wells of intellectual thought and stimulation – yet Mbongeni, with his flimsy and incomplete high school education, obtained from a poor Bantu Education school, was leading the charge. He was one of the few people in Daveyton who visited the library to read books for leisure; the library was generally frequented by students who needed the peace and quiet of the place so they could study or do their homework. On Saturdays, Mbongeni and I would walk hand in hand – another unusual scene in our neighbourhood – all the way to the library. At the library he would check out a book, and we would go and sit out on the lawn, and he would read to me. It was a very unusual romance. I was impressed and awed by his capacity to absorb information like a sponge and, in turn, impart it generously and gently to whoever cared to listen. He spoke about everything, from politics to theatre, from music to religion. He was such a breath of fresh air at a time and place where boys, when chatting up girls, would talk about parties, fashion, booze and fast cars.

But his favourite subject, obviously, was theatre. Over and over again, he would tell me a story about one or other theatre luminary who was making waves on Broadway. ‘I think one day I’ll get to Broadway.’ He would always wrap up his talk with those words, wistfully looking into the distance.

Dreaming about Broadway was not going to put bread on the table or help him buy new clothes, which he sorely needed. Meantime he and Percy were working hard at the Market Theatre, where they were rehearsing that Woza Albert! play of theirs. Wait a minute, at that time the play was still called Our Father Who Art in Heaven. To an eighteen-year-old township girl whose experience of theatre was limited to Gibson Kente plays, Woza Albert! sounded very strange. A play featuring only two people? No music, no band, no dancers? Fearing that I would betray my ignorance, I kept my reservations to myself. Much as Mbongeni had swept me up in a wave of excitement over this play, I did have my doubts.

I was not the only one to have doubts. Percy’s older brother, at whose house Percy and Mbongeni were squatting while they were rehearsing Woza Albert!, suddenly got tired of the two men. ‘Why can’t you go and find work like your age mates?’ he complained. ‘Out of my house!’

Having been kicked out of the house, the two were suddenly homeless. They sponged off whomever they encountered at the Federated Union of Black Artists (Fuba), where they’d managed to secure rehearsal space for the play. My parents and my sister sighed in relief at the sudden disappearance of the man, hoping that he was finally out of my life. Little did they know that whenever Mbongeni had some cash, he would take a taxi and come visiting in the township. Otherwise he would phone me, choosing a time when he knew I was likely to be by myself. Or I would give him the number of a public phone. We always had a plan.

It was while he was still rehearsing at Fuba that he met a fellow Natalian who organised accommodation for him in Pimville. The landlady was a kindly woman called Ignatia. She shared her standard four-roomed house with about nineteen children – mostly orphans – who slept on sofas, or in Ignatia’s bed. Mbongeni couldn’t stop talking about Aunt Ignatia’s generosity and selflessness. He was surprised that in the dog-eat-dog world of Soweto there was such a giving soul. With her permission, he got Percy to come and stay at the house in Pimville too. The house might have been very overcrowded, but it was well kept. Aunt Ignatia had trained the children well and they cleaned up after themselves.

Rehearsals of the play continued. Mbongeni and Percy had initially planned on a large cast, but because they had no money whatsoever they couldn’t convince any actors to join them for rehearsals; so, the two of them rehearsed, playing multiple roles. The training they had acquired at Gibson Kente’s company served them well. They were fit, energetic and highly focused. One person could play five, six characters with relative ease. They sang and danced well. It was in the middle of their frenetic rehearsal programme that they learned that the Market Theatre, which had become the mecca of black theatrical activity, was looking for actors. They auditioned. They didn’t get the parts. However, forever bursting with confidence – they were Gibson Kente’s boys, after all! – they told Mannie Manim, who was managing director at the Market, about their own play. It took a few months before Manim was ready to see their effort. Though the script rambled, the bristling energy at the core of their performance bowled Manim over. Later, he paired them with one of the illustrious directors of that time, Barney Simon. Initially reluctant to work with them – for political reasons he believed they were better off working with a black director – Simon finally and very reluctantly started rehearsals with Percy and Mbongeni.

Word soon travelled in the close-knit Market Theatre community that these two young men who had worked with Gibson Kente were rehearsing a new production to be directed by the great Barney Simon. The buzz attracted a colourful personality – let’s call him Bra Vusi – who made his money ‘liberating cars’ and ‘repossessing the wealth from banks’. Essentially a good soul with a shady profession, Bra Vusi ingratiated himself with Percy and Mbongeni. He gave them a generous allowance so they could buy themselves decent food, and some clothes. Mbongeni could now, with a smile, contribute a little to Aunt Ignatia’s household budget.

Mbongeni’s life was about to change. Big time. And along with it, my own life was about to change in ways I’d never imagined.