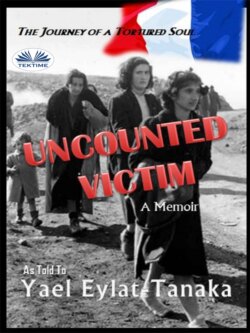

Uncounted Victim

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Yael Eylat-Tanaka. Uncounted Victim

A Memoir. As told to

Copyright © 2016, by Yael Eylat-Tanaka. All Right Reserved

Foreword

Prologue

Chapter 1. Childhood

Chapter 2. Germany Invades France

Chapter 3. Hope Can Be A Traitor

Chapter 4. Rounding Up The Jews

Chapter 5. Crossing Into Switzerland

Chapter 6. In Hiding

Chapter 7. Liberation

Chapter 8. Palestine

Chapter 9. A Shout Heard Around The World

Chapter 10 “Tarzan”

Chapter 11. Guard Duty

Chapter 12. Heartbreak

Chapter 13. Mother And Daughter

Chapter 14 “Civilian” Life

Chapter 15. Brotherly Love

Chapter 16. Moshe Dayan

Chapter 17. Of More Recent Vintage

Epilogue

A Letter To My Mother

About The Author

Отрывок из книги

The Journey of a Tortured Soul

Yael Eylat-Tanaka

.....

There were so few Jews in Valence before World War II that there was no temple or synagogue in the city. One year, however, my parents decided to conduct services in our apartment during the High Holy Days. Since a quorum of ten men is necessary to conduct the prayers, barely that number of Jewish men was found in Valence and invited to our home. My parents moved most of the furniture out of the dining room and covered the armoire with a white sheet. A Torah had been brought in from one of the temples in Lyon and placed in that makeshift Ark. The women sat in the other rooms and looked on from the doorways as the men prayed in the “sanctuary.” I vaguely remember an incident during those Holy Days when one of the men sat in the sanctuary during services and crossed his legs, putting one foot atop the opposite knee. This created quite a stir among the other men who reproached him for his lack of respect in this “holy” place. I mention this as an instance of how sacred Judaism was to my family in spite of my father’s modern attitude and edict that the children not be given any particular religious education.

That year, since we were going to have a “temple” in our home, along with many guests, my mother had my aunt, Allegra, sew a new silk dress for me. It was light blue and the skirt finely pleated. The fittings at my aunt’s house and my joy at having to wear such a delightful new dress during the Holy Days knew no bounds! Sadly, I had disobeyed my parents or gotten into some mischief the week before the festival, and I was punished where it really hurt: my vanity. I was forbidden to wear my new dress which hung ready and gorgeous for all to see on the hanger, but not on me! And I never did wear it, for I suddenly outgrew it and the dress became much too small. This disappointment marked me quite deeply, for I realized that I must have been not only a handful for my parents, but certainly quite vain. I can still hear my mother’s friends commenting what a beautiful little girl she had, and Maman trying to curb what evidently had gone to my head. My best friend had a mirror in which I admired my long curls, to my father’s despair, to the point that he vowed to cut off all my hair while I slept if I did not stop gazing into that mirror! I cannot believe that he meant it, even though I believed him then.

.....