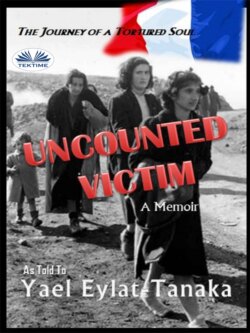

Читать книгу Uncounted Victim - Yael Eylat-Tanaka - Страница 6

Chapter 2 Germany Invades France

ОглавлениеI was 12 years old and living with my family in Bourg-les-Valence when World War II began in September of 1939. I heard the adults speaking of Neville Chamberlain, then British Prime Minister, who had gone to Germany to try and convince Hitler to be less fanatical in his politics of annexation (he had already annexed Austria and the Sunderland in Czechoslovakia. We had anticipated war after Hitler’s rise in Germany, when he finally took Danzig in Poland on September 1, 1939 (now called Gdansk). There had been international appeals and conferences to avert that catastrophe, with Neville Chamberlain returning with his slogan, “Peace in our times” by which he seemed to appease Hitler and the world. In France, we sang patriotic songs before the war challenging Hitler to come to the Maginot Line, a line of defense built along the border with Germany, but leaving the Belgian border undefended and through which the German hordes eventually invaded France. But, in the span of ten months, French forces were beaten and defeated and overrun by the German army that crossed the Maginot Line.

Whatever peace had been agreed to between France and Germany lasted just a few months, and in 1940 the French army capitulated and the German armies invaded France. The very nationalistic French media kept singing popular songs, taunting Hitler and defying him to come to the Maginot Line, a fortified bunker built between France and Germany and meant to stop the invading German armies. Instead, Hitler’s armies bypassed the front and the Maginot Line, instead crossing undefended Belgium and making their way to Paris.

One day, Rene’s best friend came to our home pale and haggard, and told us that an armistice had been asked by Maréchal Pétain and that France had lost the war. The French government had left Paris and taken refuge in Vichy, and the German forces had invaded France.

The French government retired to Vichy in the center of France under the direction of old Maréchal Pétain and Prime Minister Pierre Laval. Both of them were considered collaborators by the French population because the Vichy government was very accommodating to the occupying German army that imposed all kinds of restrictions on the French. Together with the government, two military academies, St. Cyr and Le Prytanée Militaire, left the occupied zone and installed themselves in military barracks that had been vacated by the French soldiers sent to the front. All the available food had been requisitioned by the Germans and we started having butcher shops selling horse meat which, by the way, was very tasty.

The first German orders were that every Jew in the occupied zone had to wear a yellow Star of David on their clothing. The Jews had a curfew and even though we lived in an unoccupied zone, we kept hearing that some of the French population helped the Germans arrest Jews during the night. These poor people were never heard from again.

We also learned from those who were successful in bypassing the Demarcation Line that thousands of Parisian Jews, including children, were rounded up and dropped at the Paris Velodrome d’Hiver and “forgotten” there. Those who survived the cold and exposure were taken to Auschwitz.

We lived in constant fear. We were bombarded by the allies’ planes that were trying to destroy the two French military barracks in our neighborhood, and we feared being awakened during the night to be deported, betrayed by our own compatriots.

We were hungry. Our rations included a single 200- gram piece of bread per day. Of course, we had no eggs, flour, butter, sugar or chocolate. Only horse meat was available, but that also soon disappeared from the shops, being diverted to the occupying troops.

One of the first orders imposed by the German army was a ban on any nationalistic expressions of patriotic songs or military parades in the city. The 14th of July being France’s Bastille Day, everyone was in suspense anxiously anticipating what the cadets in our city would do considering the Germans’ ban. How would they celebrate France’s Independence Day?

On the 14th of July 1940, all the cadets from St. Cyr and Le Prytanée military academies, donning their best uniforms, flaunted their disdain and paraded on the city’s boulevards where the German Commandantur had its headquarters. They sang patriotic songs, such as,

Vous avez eu l’Alsace et la Lorraine

Mais malgré tout nous resterons Français

Vous avez eu l’Alsace et la Lorraine

Mais notre coeur vous ne l’aurez jamais.

You got Alsace and Lorraine

But nevertheless we’ll remain French

You got Alsace and Lorraine

But our hearts you’ll never get.

Amazingly, there were no fearsome reprisals or punishments aside from forbidding the cadets from leaving their barracks for a month. There was great joy, as the reprisals could have been extremely severe.

Among the people who succeeded in crossing the demarcation line, one of them stands out in my mind: He was a Hungarian Jew, Mr. Spitzer, who had been living in Paris and was now trying to survive in the unoccupied zone.

He worked as a “plongeur” (dish washer) at a restaurant and used to come to our home for some companionship. In his broken French he told us that one day, as he was coming home from work, he saw his wife and children being taken away in a truck by the Germans. He knew that he was helpless and couldn’t do anything to save them. I was crying and I remember my father saying “Tu vois, tu as fait pleurer my fille.” (You see, you made my daughter cry).

His was hardly an isolated story in those days. We all feared for our lives. We all feared deportation, and worse.