Читать книгу The Facts Behind the Helsinki Roccamatios - Yann Martel - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI hadn’t known Paul for very long. We met in the fall of 1986 at Ellis University, in Roetown, just east of Toronto. I had taken time off and worked and travelled to India: I was twenty-three and in my last year. Paul had just turned nineteen and was entering first year. At the beginning of the year at Ellis, some senior students introduce the first-years to the university. There are no pranks or anything like that; the seniors are there to be helpful. They’re called “amigos” and the first-years “amigees”, which shows you how much Spanish they speak in Roetown. I was an amigo and most of my amigees struck me as cheerful, eager and young—very young. But right away I liked Paul’s laidback, intelligent curiosity and his sceptical turn of mind. The two of us clicked and we started hanging out together. Because I was older and I had done more things, I usually spoke with the authority of a wise guru, and Paul listened like a young disciple—except when he raised an eyebrow and said something that threw my pompousness right into my face. Then we laughed and broke from these roles and it was plain what we were: really good friends.

Then, hardly into second term, Paul fell ill. Already at Christmas he had had a fever, and since February he had been carrying around a dry, hacking cough he couldn’t get rid of. Initially, he—we—thought nothing of it. The cold, the dryness of the air—it was something to do with that.

Slowly things got worse. Now I recall signs that I didn’t think twice about at the time. Meals left unfinished. A complaint once of diarrhoea. A lack of energy that went beyond phlegmatic temperament. One day we were climbing the stairs to the library, hardly twenty-five steps, and when we reached the top, we stopped. I remember realizing that the only reason we had stopped was because Paul was out of breath and wanted to rest. And he seemed to be losing weight. It was hard to tell, what with the heavy winter sweaters and all, but I was certain that his frame had been stockier earlier in the year. When it became clear that something was wrong, we talked about it—nearly casually, you must understand—and I played doctor and said, “Let’s see … breathlessness, cough, weight loss, fatigue. Paul, you have pneumonia.” I was joking, of course; what do I know? But that’s in fact what he had. It’s called Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, PCP to intimates. In mid-February Paul went to Toronto to see his family doctor.

Nine months later he was dead.

AIDS. He announced it to me over the phone in a detached voice. He had been gone nearly two weeks. He had just got back from the hospital, he told me. I reeled. My first thoughts were for myself. Had he ever cut himself in my presence? If so, what had happened? Had I ever drunk from his glass? Shared his food? I tried to establish if there had ever been a bridge between his system and mine. Then I thought of him. I thought of gay sex and hard drugs. But Paul wasn’t gay. He had never told me so outright, but I knew him well enough and I had never detected the least ambivalence. I likewise couldn’t imagine him a heroin addict. In any case, that wasn’t it. Three years ago, when he was sixteen, he had gone to Jamaica on a Christmas holiday with his parents. They had had a car accident. Paul’s right leg had been broken and he’d lost some blood. He had received a blood transfusion at the local hospital. Six witnesses of the accident had come along to volunteer blood. Three were of the right blood group. Several phone calls and a little research turned up the fact that one of the three had died unexpectedly two years later while being treated for pneumonia. An autopsy had revealed that the man had severe toxoplasmic cerebral lesions. A suspicious combination.

I went to visit Paul that weekend at his home in wealthy Rosedale. I didn’t want to; I wanted to block the whole thing off mentally. I asked—this was my excuse—if he was sure his parents cared for a visitor. He insisted that I come. And I did. I came through. And I was right about his parents. Because what hurt most that first weekend was not Paul, but Paul’s family.

After learning how he had probably caught the virus, Paul’s father didn’t utter a syllable for the rest of that day. Early the next morning he fetched the tool kit in the basement, put his winter parka over his housecoat, stepped out onto the driveway, and proceeded to destroy the family car. Because he had been the driver when they had had the accident in Jamaica, even though it hadn’t been his fault and it had been in another car, a rental. He took a hammer and shattered all the lights and windows. He scraped and trashed the entire body. He banged nails into the tires. He siphoned the gasoline from the tank, poured it over and inside the car, and set it on fire. That’s when neighbours called the firefighters. They rushed to the scene and put the fire out. The police came, too. When he blurted out why he had done it, all of them were very understanding and the police left without charging him or anything; they only asked if he wanted to go to the hospital, which he didn’t. So that was the first thing I saw when I walked up to Paul’s large, corner-lot house: a burnt wreck of a Mercedes covered in dried foam.

Jack was a hard-working corporate lawyer. When Paul introduced me to him, he grinned, shook my hand hard and said, “Good to meet you!” Then he didn’t seem to have anything else to say. His face was red. Paul’s mother, Mary, was in their bedroom. I had met her at the beginning of the university year. As a young woman she had earned an M.A. in anthropology from McGill, she had been a highly ranked amateur tennis player, and she had travelled. Now she worked part-time for a human rights organization. Paul was proud of his mother and got along with her very well. She was a smart, energetic woman. But here she was, lying awake on the bed in a foetal position, looking like a wrinkled balloon, all the taut vitality drained out of her. Paul stood next to the bed and just said, “My mother.” She barely reacted. I didn’t know what to do. Paul’s sister, Jennifer, a graduate student in sociology at the University of Toronto, was the most visibly distraught. Her eyes were red, her face was puffy—she looked terrible. I don’t mean to be funny, but even George H., the family Labrador, was grief-stricken. He had squeezed himself under the living-room sofa, wouldn’t budge, and whined all the time.

The verdict had come on Wednesday morning, and since then (it was Friday) none of them, George H. included, had eaten a morsel of food. Paul’s father and mother hadn’t gone to work, and Jennifer hadn’t gone to school. They slept, when they slept, wherever they happened to be. One morning I found Paul’s father sleeping on the living-room floor, fully dressed and wrapped in the Persian rug, a hand reaching for the dog beneath the sofa. Except for frenzied bursts of phone conversation, the house was quiet.

In the middle of it all was Paul, who wasn’t reacting. At a funeral where the family members are broken with pain and grief, he was the funeral director going about with professional calm and dull sympathy. Only on the third day of my stay did he start to react. But death couldn’t make itself understood. Paul knew that something awful was happening to him, but he couldn’t grasp it. Death was beyond him. It was a theoretical abstraction. He spoke of his condition as if it were news from a foreign country. He said, “I’m going to die,” the way he might say, “There was a ferry disaster in Bangladesh.”

I had meant to stay just the weekend—there was school—but I ended up staying ten days. I did a lot of housecleaning and cooking during that time. The family didn’t notice much, but that was all right. Paul helped me, and he liked that because it gave him something to do. We had the car towed away, we replaced a phone that Paul’s father had destroyed, we cleaned the house spotlessly from top to bottom, we gave George H. a bath (George H. because Paul really liked The Beatles and when he was a kid he liked to say to himself when he was walking the dog, “At this very moment, unbeknown to anyone, absolutely incognito, Beatle Paul and Beatle George are walking the streets of Toronto,” and he would dream about what it would be like to sing “Help!” in Shea Stadium), and we went food shopping and nudged the family into eating. I say “we” and “Paul helped”—what I mean is that I did everything while he sat in a chair nearby. Drugs called dapsone and trimethoprim were overcoming Paul’s pneumonia, but he was still weak and out of breath. He moved about like an old man, slowly and conscious of every exertion.

It took the family a while to break out of its shock. During the course of Paul’s illness I noticed three states they would go through. In the first, common at home, when the pain was too close, they would pull away and each do their thing: Paul’s father would destroy something sturdy, like a table or an appliance, Paul’s mother would lie on her bed in a daze, Jennifer would cry in her bedroom, and George H. would hide under the sofa and whine. In the second, at the hospital often, they would rally around Paul, and they would talk and sob and encourage each other and laugh and whisper. Finally, in the third, they would display what I suppose you could call normal behaviour, an ability to get through the day as if death didn’t exist, a composed, somewhat numb face of courage that, because it was required every single day, became both heroic and ordinary. The family went through these states over the course of several months, or in an hour.

I don’t want to talk about what AIDS does to a body. Imagine it very bad—and then make it worse (you can’t imagine the degradation). Look up in the dictionary the word “flesh”—such a plump word—and then look up the word “melt”.

That’s not the worst of it, anyway. The worst of it is the resistance put up, the I’m-not-going-to-die virus. It’s the one that affects the most people because it attacks the living, the ones who surround and love the dying. That virus infected me early on. I remember the day precisely. Paul was in the hospital. He was eating his supper, his whole supper, till the plate was clean and shiny, though he wasn’t at all hungry. I watched him as he chased down every last pea with his fork and as he consciously chewed every mouthful before swallowing. It will help my body fight. Every little bit counts—that’s what he was thinking. It was written all over his face, all over his body, all over the walls. I wanted to scream, “Forget the fucking peas, Paul. You’re going to die! DIE!” Except that the words “death” and “dying”, and their various derivatives and synonyms, were now tacitly forbidden from our talk. So I just sat there, my face emptied of any expression, anger roiling me up inside. My condition got much worse every time I saw Paul shave. All he had were a few downy whiskers on his chin; he just wasn’t the hairy type. Still, he began to shave every day. Every day he lathered up his face with a mountain of shaving cream and scraped it off with a disposable razor. It’s an image that has become engraved in my memory: a vacillatingly healthy Paul dressed in a hospital gown standing in front of a mirror, turning his head this way and that, pulling his skin here and there, meticulously doing something that was utterly, utterly useless.

I botched my academic year. I was skipping lectures and seminars constantly and I couldn’t write any essays. In fact, I couldn’t even read anymore; I would stare for hours at the same paragraph of Kant or Heidegger, trying to understand what it was saying, trying to focus, without any success. At the same time, I developed a loathing for my country. Canada reeked of insipidity, comfort and insularity. Canadians were up to their necks in materialism and above the neck it was all American television. Nowhere could I see idealism or rigour. There was nothing but deadening mediocrity. Canada’s policy on Central America, on Native issues, on the environment, on Reagan’s America, on everything, made my stomach turn. There was nothing about this country that I liked, nothing. I couldn’t wait to escape.

One day in a philosophy seminar—that was my major—I was doing a presentation on Hegel’s philosophy of history. The professor, an intelligent and considerate man, interrupted me and asked me to elucidate a point he hadn’t understood. I fell silent. I looked about the cosy, book-filled office where we were sitting. I remember that moment of silence very clearly because it was precisely then, rising through my confusion with unstoppable force, that I boiled over with anger and cynicism. I screamed, I got up, I projected the hefty Hegel book through the closed window, and I stormed out of the office, slamming the door as hard as I could and kicking in one of its nicely sculptured panels for good measure.

I tried to withdraw from Ellis, but I missed the deadline. I appealed and appeared in front of a committee, the Committee on Undergraduate Standings and Petitions, CUSP they call it. My grounds for withdrawing were Paul, but when the chairman of CUSP prodded me and asked me in a glib little voice what exactly I meant by “emotional distress”, I looked at him and I decided that Paul’s agony wasn’t an orange I was going to peel and quarter and present to him. This time, however, I didn’t make a scene. I just said, “I’ve changed my mind. I would like to withdraw my petition. Thank you for your attention,” and I walked out.

As a result I failed my year. But I didn’t care and I don’t care. I hung around Roetown, a nice place to hang around.

But what I really want to tell you about, the purpose of this story, is the Roccamatio family of Helsinki. That’s not Paul’s family; his last name was Atsee. Nor is it my family.

You see, Paul spent months in the hospital. When his condition was stable he came home, but mostly I remember him at the hospital. The course of his illnesses, tests and treatments became the course of his life. Against my will I became familiar with words like azidothymidine, alpha interferon, domipramine, nitrazepam. (When you’re with people who are really sick, you discover what an illusion science can be.) I visited Paul. I was making the trip to Toronto to see him once or twice during the week, and often on weekends too, and I was calling him every day. When I was there, if he was strong enough, we would go for a walk or see a movie or a play. Mostly, though, we just sat around. But when you’re between four walls and neither of you wants to watch television anymore, and the papers have been read and you’re sick of playing cards, chess, Scrabble and Trivial Pursuit, and you can’t always be talking about it and its progress, you run out of ways to whittle away the time. Which was fine. Neither Paul nor I minded just sitting there, listening to music, lost in our own thoughts.

Except that I started feeling we should do something with that time. I don’t mean put on togas and ruminate philosophically about life, death, God and the meaning of it all. We had done that in first term, before we even knew he was sick. That’s the staple of undergraduate life, isn’t it? What else is there to talk about when you’ve stayed up all night till sunrise? Or when you’ve just read Descartes or Berkeley or T.S. Eliot for the first time? And anyway, Paul was nineteen. What are you at nineteen? You’re a blank page. You’re all hopes and dreams and uncertainties. You’re all future and little philosophy. What I meant was that between the two of us we had to do something constructive, something that would make something out of nothing, sense out of nonsense, something that would go beyond talking about life, death, God and the meaning of it all and actually be those things.

I gave it a good thinking. I had plenty of time to think: in the spring I got a job as a gardener for the city of Roetown. I spent my days tending flowerbeds, clipping shrubbery and mowing lawns, work that kept my hands busy but left my mind free.

The idea came to me one day as I was pushing a gas mower across an endless expanse of municipal lawn, my ears muffled by industrial ear protectors. Two words stopped me dead in my tracks: Boccaccio’s Decameron. I had read a beaten-up copy of the Italian classic when I was in India. Such a simple idea: an isolated villa outside of Florence; the world dying of the Black Death; ten people gathered together hoping to survive; telling each other stories to pass the time.

That was it. The transformative wizardry of the imagination. Boccaccio had done it in the fourteenth century, we would do it in the twentieth: we would tell each other stories. But we would be the sick this time, not the world, and we wouldn’t be fleeing it, either. On the contrary: with our stories we would be remembering the world, re-creating it, embracing it. Yes, to meet as storytellers to embrace the world—there, that was how Paul and I would destroy void.

The more I thought about it, the more I liked it. Paul and I would create a story about a family, a large family, to allow diverse yet related stories, to ensure continuity and development. The family would be Canadian and the setting would be contemporary, to make the historical and cultural references easy. But I would have to be a firm guide and not let the stories slide into mere autobiography. And I would have to be well prepared so that I could carry the story all by myself when Paul was too weak or depressed. I would also have to convince him that he had no choice, that this storytelling wasn’t a game or something on the same level as watching a movie or talking about politics. He would have to see that everything besides the story was useless, even his desperate existential thoughts that did nothing but frighten him. Only the imaginary must count.

But the imaginary doesn’t spring from nothing. If our story was to have any stamina, any breadth and depth, if it was to avoid both literal reality and irrelevant fantasy, it would need a structure, a guideline of sorts, some curb along which we blind could tap our white canes. I racked my brains trying to find just such a structure. We needed something firm yet loose, that would both restrict us and inspire us.

I hit upon it while picking weeds: we would use the history of the twentieth century. Not that the story would start in 1901 and progress up to 1986—that wouldn’t be much of a blueprint. Rather, the twentieth century would be our mould; we would use one event from each year as a metaphorical guideline. It would be a story in eighty-six episodes, each episode echoing one event from one year of the unfolding century.

To have figured out what to make of my time with Paul electrified me. I was bursting with ideas. Nothing struck me as more worthwhile than making the trip from Roetown to Toronto—commuting, imagine; that dull, work-related chore—to invent stories with Paul.

I explained it to him carefully. It was at the hospital. He was undergoing tests.

“I don’t get it,” he said. “What do you mean by ‘metaphorical guideline’? And when does the story take place?”

“Nowadays. The family exists right now. And the historical events we choose will be a parallel, something to guide us in making up our stories about the family. Like Homer’s Odyssey was a parallel for Joyce when he was writing Ulysses.”

“I’ve never read Ulysses.”

“That doesn’t matter. The point is, the novel takes place in Dublin on a single day in 1904, but it’s named after an ancient Greek epic. Joyce used the ten years’ wandering of Ulysses after the Trojan War as a parallel for his story in Dublin. His story is a metaphorical transformation of the Odyssey.”

“Why don’t we just read the book aloud since I’ve never read it?”

“Because we don’t want to be spectators, Paul.”

“Oh.”

“To start with, we have to decide where the family lives.”

He was looking at me blankly. He was sceptical and tired—but I insisted. I even got a touch annoyed. I didn’t use any of the D words, but they were in the air. His face crumpled and he started to cry. I apologized immediately. Yes, we would read Ulysses aloud, what a good idea. And then—why not?—War and Peace.

I had left his room, was stepping into the elevator, when a long shout exploded in the corridor.

“Helsinkiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii!”

I smiled. You see, Paul and I were on the same wavelength. We were young, and the young can be radical. We’re not encrusted with habits and traditions. If we catch ourselves in time, we can start all over. So the story would take place in Helsinki, the capital of Finland. A good choice. A faraway city where neither of us had been would be much easier for our fancy to play with than one that was right in front of our eyes. I returned to Paul’s room. His face was still red from shouting.

I asked him about the name of the family. He pouted his lips and narrowed his eyes and thought for a moment. Then he expelled a sound: “Roccamatio”. What? “The Roccamatios—Rok-kah-MAH-tee-ohs.” I wasn’t keen on that one. Not very realistic. Something more Nordic-sounding might be better, no? But Paul insisted: the Roccamatios—Rok-kah-MAH-tee-ohs, he repeated—were a Finnish family of Italian extraction. So be it. The Helsinki Roccamatios were located and baptized. Their story was waiting to be told. We agreed on the rules: I would be the judge of what was fictionally acceptable; transparent autobiography was forbidden. The story would take place nowadays, the mid-1980s. Each episode would be related in one sitting and would resemble one event from a consecutive year of the twentieth century. We would alternate in telling the story; I would have the odd years, Paul would have the even years. We discussed what we knew about Helsinki and agreed on the following: one, it had a population of one million inhabitants; two, it was the capital of Finland in every way—political, commercial, industrial, cultural, etc.; three, it was an important port; four, it had a small but fractious Swedish-speaking minority; and five, Russia always weighed heavily on the mood of the nation. Finally, we agreed that the Roccamatios would be a secret between the two of us.

We decided that after a period of reflection and research, I would start with the first episode. I brought Paul a pen, some paper and a three-volume work called A History of the 20th Century. His father set a small bookcase with wheels beside his bed and filled it with all thirty-two volumes of the 15th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Now understand that you’re not going to hear the story of the Helsinki Roccamatios. Certain intimacies shouldn’t be made public. They should be known to exist, that’s all. The telling of the story of the Roccamatios was difficult, especially as the years went by. We started brave and strong, arguing all the time and interrupting each other constantly, surprising ourselves with our cleverness and originality, laughing a whole lot—but it’s so tiring to re-create the world when you’re not at the peak of health. Paul wouldn’t be so much unwilling—he would still object or redirect me with a word or a scowl—as unable. Even listening became tiring.

The story of the Helsinki Roccamatios was often whispered. And it wasn’t whispered to you. Of these AIDS years, all I have kept—outside my head—is this record:

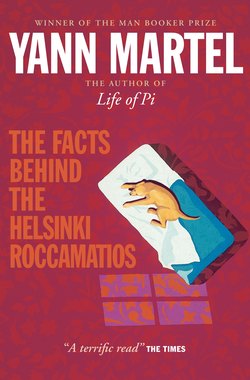

The Facts behind the Helsinki Roccamatios

1901—After a reign of sixty-four years, Queen Victoria dies. Her reign has witnessed a period of incredible industrial expansion and increasing material prosperity. In its own blinkered and delusional way, the Victorian age has been the happiest of all—an age of stability, order, wealth, enlightenment and hope. Science and technology are new and triumphant, and Utopia seems at hand.

I begin with an ending, with the death of Sandro Roccamatio, the patriarch of the family. It is dramatic, and it allows me to introduce the family members, who are all at the funeral.

1902—Under the forceful leadership of Clifford Sifton, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s Minister of the Interior, the settlement of Canada’s west is in full swing. Sifton sends out millions of pamphlets in dozens of languages and strings a net of agents across northern and central Europe. Ships that have just dumped their Canadian wheat on the Old Continent bring home the catch. In less than a decade the population of the Prairies increases by a million inhabitants and wheat production jumps fivefold. Laurier proclaims to the booming country, “The twentieth Century belongs to Canada.”

1903—Orville and Wilbur Wright fly at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina. Their powered machine, “Flyer 1” (now popularly called “Kitty Hawk”), stays in the air for twelve seconds on its first flight, fifty-nine seconds on its fourth and last.

1904—As a direct result of the Dreyfus affair, Prime Minister Emile Combes of France introduces a bill for the complete separation of Church and State. The bill guarantees complete liberty of conscience, removes the State from having any say in the appointment of ecclesiastics or in the payment of their salaries, and severs all other connections between Church and State.

A routine to our storytelling has already developed. It’s nearly a ceremony. First, and always first, we shake hands every time we meet, like the Europeans. Paul takes pleasure in this, I can tell. If there’s a need, we deal with health and therapy. Then we small-talk, usually about politics since we’re both diligent newspaper readers. Finally, after a short pause to collect ourselves, we get on with the Roccamatios.

1905—The German monthly Annalen der Physik publishes papers by Albert Einstein, a twenty-six-year-old German Jew who works as an examiner in a patent office in Bern, Switzerland. The Special Theory of Relativity is born. There is energy everywhere. E = mc2, as Einstein puts it.

1906—Tommy Burns defeats Marvin Hart to become the first (and only) Canadian to win the world heavyweight boxing championship. Burns defends his title eleven times in three years, notably knocking out the Irish champion Jem Roche in 1 minute and 28 seconds, the shortest heavyweight title defence ever.

Paul is nearly well. He is plagued by minor ills—night sweating here, diarrhoea there—and a lack of energy, but it’s nothing unmanageable. He is at home, and as he has never been sick a day in his life until now, the routine of illness has an exotic appeal. He is started on a program of azidothymidine (AZT) and multivitamins, and he visits the hospital every week, sometimes staying overnight. He likes the hospital. The omnipotent men and women in white, their scientific jargon, the innumerable tests, the impeccable cleanliness of the place—they exhaust and reassure him. His mood is good.

We make plans. We speak of travel. I have travelled some, Paul less, mostly with his family, and we both see travel as essential to growth, as a state of being, as a metaphor for inner journeying. Disdaining the well-worn path, we hardly speak of Europe. We are magi, not tourists. After touching on Iceland, Portugal, Bulgaria and Poland, our star leads us to other lands, to Turkey and Yemen, to Mexico and Peru and Bolivia, to South Africa and the Philippines, to India and Nepal.

1907—A new strain of wheat, Marquis, is sent out to Indian Head, Saskatchewan, for testing. It is the result of an exhaustive scientific selection process, the credit for which goes to Charles Edwards Saunders, cerealist at the Ottawa Experimental Farm. The new strain’s response to Saskatchewan conditions is phenomenal. It is resistant to heavy winds and to disease, and it produces high yields that make excellent flour. Most importantly it matures early, thus avoiding the damage of frost and greatly extending the areas of Alberta and Saskatchewan where wheat can be grown. By 1920, Marquis will make up ninety per cent of prairie spring wheat, helping make Canada one of the great breadbaskets of the world.

If I’m not distracted by my job or by thoughts of food, transportation and the like, I think of the Roccamatios. They are my mind’s natural focus. I have to find historical events. Then I have to think of plot and parallel, of the way in which my story will resemble the historical event, whether in an obvious way or a subtle way, for one symbolic moment (at the beginning or at the end?) or all along. These thoughts pester me, challenge me, make me go on. I am hardly aware of my workaday life.

1908—Ernest Thompson Seton, author, naturalist and artist, organizes the Boy Scouts of Canada. The aim of the organization, like that of the Girl Guides founded two years later, is to foster good citizenship, decent behaviour, love of nature, and skill in various outdoor activities. The Scouts follow a moral code and are encouraged to perform a daily good deed. They go camping, swimming, sailing and hiking. They undertake community service projects. Their motto is “Be Prepared”, and they shake hands with the left hand.

I had not envisioned the Roccamatios so ambitiously. Marriages, the runaway daughter, the bitter but liberating divorce, childbirth, entrepreneurial success, romance, community leadership—they are a dynamic family. Paul and I go about them briskly. I meant for us to alternate years, but so far they have been more of a co-operative invention.

But there are clouds on the horizon. The year 1909 is mine. I see trial and error in the story I make of it. Paul sees trial and fraud. It’s the first time we quibble. And I’m troubled by his story for 1910.

1909—Commander Robert E. Peary, on his third attempt, claims to reach the North Pole. Though generally accepted, the claim is questioned by many because of the inadequacy of his observations and the incredible timetable of travelling he has submitted.

1910—Japan, increasingly militaristic and determined to expand its power and influence, annexes Korea and begins to exploit the country’s people and resources entirely for its own benefit. Koreans are denied freedom of speech, of assembly and association, even of going to school in their own language.

I launch the Roccamatios into the hurly-burly of Helsinki municipal politics!

1911—A federal election is called in Canada. The dominant issue of the campaign is reciprocity, an agreement to lower tariffs between Canada and the United States. Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier favours reciprocity. Conservative Opposition leader Robert Borden does not. Eastern Canadian manufacturers cry that such an economic accord will be the first step in a political takeover. Certain statements by influential Americans—“I hope to see the day when the American flag will float over every square foot of the British North American possessions, clear to the North Pole,” says Champ Clark, Speaker of the House of Representatives—seem to justify those fears. Laurier and his Liberals go down to a resounding defeat and Borden becomes prime minister.

Paul’s moods are changing. I think he’s starting to realize what he’s in for. Initially his pills and injections were a source of delight. Here comes health, they signalled to him. You’ll beat this. But health eludes him, and he’s angry about it. He still takes his medicines religiously, but they taste bitter now, not sweet. In 1912, the Minimum Wage law is passed in England; Roald Amundsen reaches the South Pole; a beautiful bust of Queen Nefertiti is discovered in Egypt by German archaeologists; Edgar Rice Burroughs publishes his first Tarzan stories; Marcel Duchamp shows his Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. But Paul will have none of these. His story, about a mugging, is plain, simple and brutal.

1912—After a siege of five hours in Choisy-le-Roy, a suburb of Paris, anarchist Jules Joseph Bonnot is killed. Bonnot and his gang, la bande à Bonnot as they are known, have been terrorizing French society with the jaunty unconcern with which they shoot tellers, guards, passers-by, policemen, dwellers and drivers during their bare-faced bank robberies, break-ins and car thefts. In the final attack on his holdout, the authorities deploy against a solitary Bonnot three artillery regiments and five police brigades, and they use guns, heavy machine guns and dynamite. Bonnot is found, still alive, wrapped in a mattress. He is finished off. There are more than thirty thousand spectators at the siege.

Lasting optimism has one essential ally: reason. Any optimism that is unreasonable is bound to be dashed by reality, leading to even more unhappiness. Optimism, therefore, must always be illuminated by the gentle, purging light of reason and be unshakeably grounded in sanity of mind, so that pessimism becomes a foolish, shortsighted attitude. What this means—reasonableness being the tepid, inglorious thing it is—is that optimism can arise only from small but undeniable achievements. In 1913, I put my best foot forward.

1913—The zipper is patented.

Paul has been hospitalized. He’s having a relapse of Pneumocystis carinii. He’s put on dapsone and trimethoprim again, but this time he suffers side effects: a fever, and a rash all over his neck and chest. He’s amazingly thin; he hardly eats and his diarrhoea is intractable. He has a tube up his nose. In his story, Marco Roccamatio has a serious fall-out with his brother Orlando.

1914—In Sarajevo, for the sake of a South Slav nationalist dream, nineteen-year-old Gavrilo Princip pulls the trigger of his revolver and starts the First World War.

Austria declares war on Serbia.

Germany declares war on Russia.

Germany declares war on France.

Germany declares war on Belgium.

Great Britain (and with her Canada, India, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland) declares war on Germany.

Montenegro declares war on Austria.

Austria declares war on Russia.

Serbia declares war on Germany.

Montenegro declares war on Germany.

France declares war on Austria.

Great Britain declares war on Austria.

Japan declares war on Germany.

Japan declares war on Austria.

Austria declares war on Belgium.

Russia declares war on Turkey.

Serbia declares war on Turkey.

Great Britain declares war on Turkey.

France declares war on Turkey.

Egypt declares war on Turkey.

I tell Paul 1914 was the year the Panama Canal was opened and wouldn’t it make for a more pleasant story?

“Your history is biased,” he replies.

“So is yours,” I shoot back.

“But mine is the correct bias.”

“How do you know?”

“Because it accounts for the future.”

I can’t understand it. I have read of people who have AIDS who live for years. Yet week by week Paul is getting thinner and weaker. He is receiving treatments, yes, but they don’t seem to be doing much, except for his pneumonia. Anyway, he doesn’t seem to have any particular illness, just a wasting away. I ask a doctor about it, nearly complain about it. He’s standing in a doorway. He listens to my litany silently—he’s a big, unshaven man and his eyes are red—and then he doesn’t say anything and finally he says in a low, measured voice, “We’re—doing—our—best.”

It’s my turn. I must be careful. I refuse to invoke the war. I would like the extension of suffrage to women in Denmark. But a story of reconciliation would not please Paul. I consider the publication of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. It’s too dark. I must neither give in to Paul, nor ignore him. I must steer between total abstraction and grim reality. I don’t know what to do. I go for the ambiguous.

1915—Alfred Wegener, a German meteorologist and geophysicist, publishes The Origin of Continents and Oceans, in which he gives the classic expression of the controversial theory of continental drift. Wegener postulates that a mother landmass, which he names Pangaea, broke up some 250 million years ago, the pieces drifting apart at the rate of roughly an inch a year, thus producing the continents of today.

“An inch a year?” Paul smiles. He likes my story, too. But he won’t be stopped.

1916—Germany declares war on Portugal.

Austria declares war on Portugal.

Romania declares war on Austria.

Italy declares war on Germany.

Germany declares war on Romania.

Turkey declares war on Romania.

Bulgaria declares war on Romania.

More tests. Paul has something called cytomegalovirus, which may account for his diarrhoea and his general weakness. It’s a highly disseminating infection, could affect his eyes, lungs, liver, gastrointestinal tract, spinal cord or brain. There’s nothing to be done. No effective therapy exists. Paul is speechlessly depressed. I give in to him.

1917—The United States declares war on Germany.

Panama declares war on Germany.

Cuba declares war on Germany.

Greece declares war on Austria, Bulgaria, Germany and Turkey.

Siam declares war on Germany and Austria.

Liberia declares war on Germany.

China declares war on Germany and Austria.

Brazil declares war on Germany.

The United States declares war on Austria.

Panama declares war on Austria.

Cuba declares war on Austria.

For 1918 Paul wants to use further declarations of war—Haiti and Honduras declared war on Germany, he informs me—but for the first time I use my power of veto and declare these fictionally unacceptable. Nor do I accept the publication of Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West, in which Spengler argues that civilizations are like natural organisms, with life cycles implying birth, bloom and decay, and that Western civilization has entered the last, inevitable stage of decay. Enough is enough, I tell Paul. There is hope. The sun still shines. Paul is angry, but he is tired and he submits. I think he was expecting my censure, for he surprises me with a curious event and a fully prepared story.

1918—After an extensive study of globular clusters—immense, densely packed groups of stars—Harlow Shapley determines that the centre of the Milky Way Galaxy, our galaxy, is in the Sagittarius constellation and that our solar system lies about two thirds of the way from this centre, some thirty thousand light years away.

“Isn’t it grand,” I say.

“Aren’t we lonely,” he replies.

His story—of Orlando, of alcoholism—is ugly.

1919—Walter Gropius becomes head of the Bauhaus, a school of art, design and architecture in Weimar, Germany. Under his leadership, the teachers at Bauhaus break with the past. They emphasize geometrical forms, smooth surfaces, regular outlines, primary colours and modern materials. Just as importantly, they take to mass-manufacturing techniques, making their functional, aesthetically pleasing objects affordable to everyone. Never before have objects of daily life looked so good to so many.

“This AZT is exhausting,” says Paul. He is anemic because of it and receives blood transfusions regularly.

In 1920, I forbid the publication of Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, in which Freud posits an underlying, destructive drive, Thanatos, the death instinct, which seeks to end life’s inevitable tensions by ending life itself. Paul changes historical events while keeping the same Roccamatio story.

1920—Dada triumphs. Born in Zurich during the depths of the First World War and spread by a merry, desperate band of writers and artists, including Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp, Jean Arp, Richard Hulsenbeck, Raoul Hausmann, Kurt Schwitters, Francis Picabia, George Grosz and many others, Dadaism seeks the demolition of all the values of art, society and civilization.

Paul tells me over the phone that he’s developing Kaposi’s sarcoma. He has purple, blue lesions on his feet and ankles. Not many, but they are there. The doctors have zeroed in on them. He will be put on alpha interferon and undergo radiation therapy. Paul’s voice is shaky. But we agree, we strongly agree, with what the doctors have said, that radiation therapy has been found to be successful against localized Kaposi’s sarcoma, and he’s only got it on his skin, in fact, only on his feet, and it doesn’t hurt, and at least his lungs are fine. I promise to come by the hospital.

Paul is quiet. He is in his usual, favourite position: lying on his back against a fastidiously constructed pyramid of three pillows.

1921—Frederick Banting and Charles Best discover insulin, the glucose-metabolizing hormone secreted by the pancreas. It is immediately and spectacularly effective as a therapy for diabetes. The lives of millions are saved.

I have just started my story when Paul interrupts me.

“In 1921, Albert Camus died in a car crash.”

He doesn’t say anything more. I continue until he interrupts me a second time.

“In 1921, Albert Camus died in a car crash.”

“Paul, he didn’t. Camus died in 1960.”

“No, Albert Camus died in a car crash in 1921. He was a passenger in a Facel-Vega. Never heard of it, have you? It was a small series, French copy of a Chrysler, not very road-tested. Camus and some friends were returning—”

“Paul, what are you doing?”

“They were returning to Paris from the Lubéron, where Camus had bought a beautiful white house with his Nobel money. The road was—”

“Okay, that’s enough.”

“The road was straight and dry and empty. Along the road were trees. Suddenly—an axle that broke? a wheel that blocked?—for no reason, the car—”

“You’re not following the rules, Paul. You’re chea—”

“THE CAR SLID and hit a tree. Camus was killed instantly—”

“In 1921, Banting and Best discover insulin, the glu—”

“In 1921, Camus was killed instantly—”

“The glucose-metabolizing hormone—”

“By a tree—”

“By a hormone—”

“In 1921, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and it killed—”

“Ha! In 1921, Banting and Best—”

“In 1921, the bomb was dropped and it killed—”

“It is spectacularly effective as—”

“It killed—”

“Is spectacularly effective—”

“It ki—”

“Is effective.”

“It—”

“So, so effective.”

He’s tiring. I can sense he will submit in a moment.

“IT WAS DROPPED AND IT KILLED CAMUS!”

He shrieks this in a tone of voice that chills me and shuts me up instantly. He’s glaring at me, wild-eyed. I’m thinking, What have you done, you idiot? when he lunges for me. I’m startled and pull back, but he’s going to fall to the floor, so I catch him. I’m amazed at how light he feels. He punches me twice in the face, but he’s so weak it doesn’t hurt. He begins to sob.

“It’s all right, Paul, it’s all right. I’m sorry,” I tell him softly. “It’s all right. I’m sorry. Take it easy. Listen, I’ve got something better. In 1921, they didn’t discover insulin. In 1921, Sacco and Vanzetti were sentenced to death. Sacco and Vanzetti, Paul, Sacco and Vanzetti, Sacco and Vanzetti.”

His tears are flooding his face and dripping onto my arms. I lift him and push him back onto the bed.

“Sacco and Vanzetti, Paul, Sacco and Vanzetti. It’s all right. I’m sorry. Sacco and Vanzetti, Sacco and Vanzetti, Sacco and Vanzetti.”

I get a wet facecloth and wipe my arms and gently wipe his face. I comb his hair with my fingers.

“It’s all right, Paul. Sacco and Vanzetti, Sacco and Vanzetti, Sacco and Vanzetti, Sacco and Vanzetti.”

I improvise a grim story. Sometimes our stories are short on plot, but by means of details left unexplained, by means of fertile ambiguities, they nonetheless resonate in the way of a painting, static but rich. But here it’s not at all like that. There is little plot and little meaning. The story just stumbles along, unbelievable, unexplainable. Loretta Roccamatio drowns herself.

1921—Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, both poor Italian immigrants and anarchists, are found guilty and sentenced to death for two murders committed during a robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts. In spite of flaws in the evidence, irregularities at their trial, accusations that the judge and jury were prejudiced against their political beliefs and social status, evidence that pointed to a known criminal gang, in spite of worldwide protests and appeals for clemency, Sacco and Vanzetti will be executed in 1927.

Paul is put on anti-depressants—amitriptyline at first, then domipramine. It will take about two weeks before they become effective. In the meantime he is kept under close surveillance, especially at night, when he sleeps only in fits. The clinical psychologist comes by nearly every afternoon. I call Paul up to six times a day.

1922—Benito Mussolini, at the age of thirty-nine, becomes the youngest prime minister in Italian history, and the first of Europe’s twentieth-century fascist dictators.

“I can feel them in my blood. I can feel each virus as it flows up my arm, crosses my chest, goes into my heart and then shoots out to one of my legs. And I can’t do anything. I just lie here waiting, knowing it’s going to get worse,” he says.

He’s so fragile. I give in to him again.

1923—Germany is incapable of making its payments on the war reparations imposed by the Allies in the Treaty of Versailles (set at the equivalent of thirty-three billion dollars). France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr district to force compliance. The German government blocks all reparation deliveries and encourages passive resistance. The French and Belgians respond with mass arrests and an economic blockade. The German economy is devastated, and its government begins to founder. The ground is fertile for extremists.

Paul is plainly waiting for me. He’s bored. Strange how this illness, which aims to rob him of time, leaves him with so much of it on his hands.

1924—Vladimir Lenin, whose health has been precarious for the last eighteen months, dies of a stroke at the age of fifty-four. The secretary general of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, Joseph Stalin, whom Lenin had unsuccessfully tried to remove, starts an extravagant cult of the deceased leader, thus portraying himself as Lenin’s greatest defender.