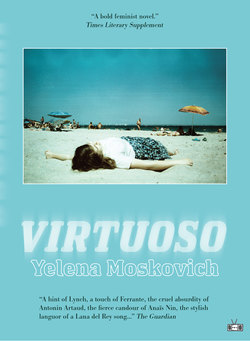

Читать книгу Virtuoso - Yelena Valer'evna Moskovich - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe new girl

Milena’s family moved out, and in came a new one. A bird-eyed mamka in a heavy fox-fur coat, a stubble-faced papka with a hernia-type stride, and a little raven-girl.

*

It was almost December. I was six and the new girl was six too. I saw her in the courtyard from my window, holding her winter hat in a small mittened fist, the top of her head sleek with dark hair. She turned to look at the buildings and I saw her left eye was slightly puffed up, and below it a streak of violet-blue. Then she looked up, straight at my window. Her pupils pointed into mine.

New Year and my birthday came around and a couple of the families in the building celebrated together as usual, except that year, the new one was invited too. All of us children knew each other except for the little raven-girl, so we all just stood around and stared at her, and she crouched against the wall and leaned her spine into the light socket, glaring back at us. Slavek’s mamka said, “What’s the matter with you all standing like stones? Go play.” She meant inside, it was a holiday, she wasn’t kicking us out into the courtyard. Plus it was snowing. Anyway, the adults quickly forgot about us and got drunk and opened and closed the window to smoke or coat the tops of their glasses of liquor with snowflakes. Since the Communist takeover in 1948, the Czechoslovak people had grown less and less interested in politics or having opinions about anything bigger than their neighborhood or family. They planned their countryside summer holidays, they drank, they bickered, they recited poetry, they went to bed.

Some of the kids snuck in sips. Slavek was already getting drunk, and his little cheeks flushed as he ran around his father’s legs, saying, “Papka, Papka, show us the knife!” It was the famed knife, with a thin snake coiled on the metal handle, that Slavek’s father’s father had apparently killed a Nazi soldier with—slicing him right across the throat below the Adam’s apple—but Slavek’s father just used it to shear a chicken’s skin in the kitchen sink or sharpen the ends of electrical wires. “Not now,” Slavek’s papka said and he pushed the boy out of the way. Slavek twirled a bit, then played swords with my brother, then vomited by the couch. After the women cleaned it up, his father put a hand on his son’s shoulder, knelt down and said, “Now, Slavek, if you drink the booze, you gotta keep it down.”

Slavek pouted, then murmured, “I’m sorry I yacked, Papka …”

*

The raven-girl and I stayed still like stones and stared at each other until the countdown began. Ten … Nine … Eight … All the adults were hurriedly refilling their glasses. Three … Two … But suddenly the raven-girl sprung away from the wall and ran and threw her limbs out greedily and sang a loveable song in a nasty voice. Her mamka tried to pull her down by her wrists, but the girl kept springing back up until her mamka gave her a sharp smack to the back of the head and her sleek black hair whisked up. The girl stopped, touched her skull with her palms, then grew very quiet.

Her mamka excused her right away and told everyone not to mind it too much—her little girl was prone to these fits of stagecraft and this was precisely why they called her the Malá Narcis, because she’s a Little Narcissus who can’t get enough of herself from time to time. The other kids started laughing with their mouths closed, the sound bursting out like spit. The adults turned the music up and began to dance, now that it was a new year, and the raven-girl looked around, then crawled under a chair. She sat there, watching everyone’s calves. It was a couple of minutes past midnight and I was officially seven years old. I went over to her, crouching down in such a way as to try not to mess up my dress in case my mamka was watching, and crawled under the table to sit near her. She looked over at me. I sucked my lips in, then let them go. “Hey,” I said. Then we both looked at everyone’s calves. I saw my mamka’s knee slide past her daddy’s trouser leg. I saw his sock showing as he took a step back to the beat, the hem of his gray suit trousers lowered because of his long legs. I saw her mamka’s white heel cross over and her tanish-colored stocking crease behind the knee. “I’m Zorka,” I heard next to me. When I looked over at her, she was picking her nose.

*

Zorka. She had eyebrows like her name.

*

Aeque pars ligni curvi ac recti valet igni. Crooked logs make straight fires.