Читать книгу Contours of White Ethnicity - Yiorgos Anagnostou - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Why White Ethnicity? Why Ethnic Pasts?

[T]he search or struggle for a sense of ethnic identity is a (re-)invention and discovery of a vision, both ethical and future-oriented. Whereas the search for coherence is grounded in a connection to the past, the meaning abstracted from that past, an important criterion of coherence, is an ethic workable for the future.

—Michael Fischer, “Ethnicity and the Post-modern Arts of Memory”

As more of us anthropologists from the borderlands go “home” to study “our own communities,” we will probably see increasing elisions of boundaries between ethnography and “minority discourse,” in which writing ethnography becomes another way of writing our own identities and communities.

—Dorinne Kondo, “The Narrative Production of ‘Home,’ Community, and Political Identity in Asian American Theater”

IN THIS WORK I explore the social category of “white ethnicity” in the United States. A classification that emerged and gained currency during the civil rights era, white ethnicity refers to hyphenated populations that trace their origins to Europe but also to countries and areas in relative proximity to it. This ascription incorporates both ethnic and racialized dimensions, attaching to these populations both cultural attributes and inescapable racialized overtones. It indicates, therefore, how white ethnics are placed in multiple, yet interrelated, systems of difference within the nation. On the one hand, groups such as Armenian Americans, Greek Americans, Jewish Americans, Irish Americans, Italian Americans, and Polish Americans are recognized as distinctly ethnic, claiming unique cultures, histories, and religions. The Americanization of these populations, on the other hand, has entailed a specific kind of assimilation, their eventual incorporation into whiteness. It is this racialization that marks these groups in counterdistinction to “nonwhite” racial minorities. Therefore, the ethnoracial label “white ethnic” simultaneously accomplishes two distinct classificatory functions. On the one hand, the racialized ascription places these collectives within the boundaries of whiteness, pointing to their current entrenchment as white in the national imagination. On the other hand, the ethnic marker attaches a cultural hue that differentiates these populations from unmarked whiteness. It is often thought that white ethnics possess culture, in contrast to the cultureless whiteness of the general population. Racially denigrated and classified as nonwhite in the past, people now designated “white ethnics” define themselves against the backdrop of complex social and political struggles over assimilation and cultural preservation, and histories of brutal symbolic and physical violence over their racial and ethnic place in American society.

In this book I analyze the ways in which one specific group of white ethnics, Greek Americans, represent themselves, undertaking this task from a specific vantage point: I examine how their past is made to matter in the present. I probe, in other words, the enduring relevance of ethnic pasts for the contemporary social imagination. Specifically, I investigate how practices and values associated with the past and glossed as “tradition,” “folklore,” “heritage,” “custom,” or “immigrant culture” are endowed with significance today. I analyze how various pasts are used to create identities and communities and to imagine the future of ethnicity. I identify specific texts and practices where such pasts are produced, and I investigate their social and political valence. I ask why and how selective pasts are retained, reworked, dismantled, discarded, or contested in the making of ethnicity. I illuminate the visions of social life that these engagements with the past endorse and what all of this tells us about present-day white ethnicity.

My aim here is to provide an analysis of how these pasts are produced and by whom, of what interests they advance and for whom. I am interested, that is, in the poetics and politics of white ethnic pasts. In this analysis, I wish to initiate a critical discussion that investigates academic and popular understandings of ethnic whiteness. I frame this category as a contested, heterogeneous cultural field whose complexity and relevance for social life has been downplayed, even maligned, in larger debates about diversity. I argue that bringing the past into the present to produce usable ethnic pasts illuminates dimensions of white ethnicity that discussions on American pluralism cannot afford to ignore.1

I strive to focus attention on the notion that ethnic pasts are always plural—not singular or monolithic—and inform the present in ways that are not always clearly discernible. Such perspective demands a bold critical intervention. I intervene in dominant academic and popular representations of ethnicity that tend to erase this diversity and, in the process, take a step toward mapping how multiple pasts give texture to the contours of the field of ethnic whiteness in the United States.

My project emerges from and participates in a number of intersecting academic conversations in anthropology, cultural studies, ethnic and racial studies, folklore, modern Greek studies, sociology, and women’s studies. One common thread in these discussions involves the cultural politics framing the social production of the past. As a domain made rather than found, the past generates passionate struggles over its meaning. Ownership of the past is an important power relation, one grounded in the ability of particular social groups to establish those versions of historical truth that serve their own interests. One must therefore pay attention to the political and social implications associated with questions about who narrates the past and who is excluded—and for what purpose. These are but a few of the important issues discussed by the current burgeoning academic interest in cultural memory, tradition, heritage, and historical consciousness. The stakes in the way in which critical scholarship engages with these questions are high. The construction of usable pasts today guides how ethnicity is imagined tomorrow. Ethnic memory, as Michael Fischer (1986) puts it, is “or ought to be, future, not past, oriented” (201). Or, in the words of Raymond Williams (1977), those traditions selected to “ratify the present” powerfully “indicate directions for the future” (116).2

In this introduction, I explore through various paths the significance of the past for white ethnicity. One such path leads to a recent debate over the depiction of early twentieth-century immigrants and illuminates the point that what could count as a past is a contested, problematic site within an ethnic collective. In revisiting this dispute, I bring to the fore a concept often forgotten in popular thought about ethnicity, namely that a white ethnic group is never a uniform, homogeneous entity. But because this heterogeneity is often contained, I pursue a discussion of how dominant narratives of American multiculturalism manage the boundaries of ethnic diversity. Having established white ethnicity as a terrain of contested meanings about the past, I continue exploring its constructions, this time focusing on how this category is discussed in the academy. This mapping helps me situate my own contribution to the debates. I identify the specific terrain of my analysis—Greek America—discuss my methodology—critical readings of what I call “popular ethnography”—and acknowledge my politics of knowledge—an interventionist critical scholarship that emanates from a minor academic field, modern Greek studies.

Who Are the White Ethnics?

One of my aims is to destabilize the understanding of white ethnicity as a uniform category. I do not, of course, neglect the racial privileges enjoyed collectively by white ethnics, and I closely analyze the dominant narratives that seek to fix the meaning of a group as a homogeneous collective. But I am also interested in mapping pluralities, marginalized perspectives, and the struggles over which pasts count as meaningful in the present. As a way of entering the complexity of this terrain, I trace here a specific contour of this struggle as it was expressed in the conflict over ethnic self-representation in a highly visible cultural institution, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum.

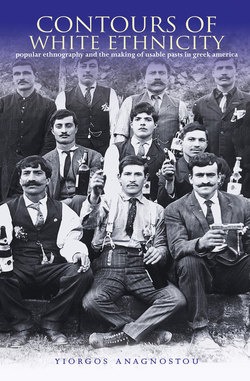

In her cultural history of Greek America, An Amulet of Greek Earth: Generations of Immigrant Folk Culture (2002), historian, folklorist, and fiction writer Helen Papanikolas features an archival photograph whose exhibit in the Ellis Island Immigration Museum stirred heated controversy. Posing for the camera is a group of immaculately dressed male immigrants in Utah in 1911. They are coal miners from the island of Crete. Gazing defiantly at the photographer, they conspicuously display their prized possessions: elegant suits, brand-new guns, and bottles of alcoholic beverage. Destined for consumption by relatives, or possibly prospective brides in the ancestral homeland, the snapshot captures a particular moment in the complex encounter between the immigrants and American modernity. In relation to the economy of labor, the photograph exemplifies a specific kind of performance. The laborers have meticulously scrubbed off those markers that scar their working-class bodies. The experience of dangerous, low-paying, dirty, and physically taxing labor associated with mining and railroad construction is rendered invisible. The body politic of labor is bracketed off for the sake of a photographic inscription that flaunts material possessions, showcases well-being, communicates vitality, and advertises economic progress. Paradoxically, as the men sport American modernity, they simultaneously declare their defiance to it. The brandishing of guns and alcohol stands as a potent symbol of competitive Cretan masculinity, proclaiming that local culture remains central to immigrant identity. In one crucial aspect, modernity does not compromise the past but enhances it. Surely, the signs of prosperity in the New World legitimize the immigrants’ break from the agricultural past, specifically their subjection of the self to migrant labor under conditions of industrial capitalism. At the same time, this material success amplifies the defiant male performance of enduring transnational continuities, a posture destined for domestic visual consumption.

A document of regional and gender pride in the past, the snapshot has sparked contemporary controversy. Its meaning has become contested. An obstinate artifact of a bygone immigrant era, the image currently appears in a variety of places (including the cover of this book). Readers of literature may be familiar with it from the novel Days of Vengeance, whose author, Harry Mark Petrakis, “[admired] the photo so much that he used it” to illustrate the cover (Georgakas 2003a, 46).3 Through this literary venue, the photograph has gained prominence as a document of Greek immigrant social history. Yet its display in the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in New Jersey—credited to Papanikolas’s curatorial decision—has stirred fanatical intraethnic dissent. Ever sensitive to the politics of cultural representation, some Greek Americans approach the photograph as a site of memory that is better forgotten than nationally commemorated. A New York–based lobbying group has “for years” been pressing the museum “to get the photo taken down and replaced with a wedding or some other conventional scene. They feel the photo is defamatory to the Greek image and not at all representative of ethnic values” (ibid.). The specific objection, as reported by Nick Smart (2005), is that it makes Greek America “‘look like a Greek Mafia,’ violent and intemperate” (119), a criticism that invokes the museum’s exhibition politics: the museum “makes no reference to the immigrant underworld of Sicilian mafiosi and Jewish prostitutes” (Lowenthal 1996, 160). The dissenters’ tactics have been aggressive and have included personal harassment. Commenting on this discord, Zeese Papanikolas (2003) offers the following testimony about his mother’s experience: “For years, wherever … [she] spoke and read on the East Coast she was shadowed by a Greek American woman who expressed her outrage at this horrible view of Greek immigrants with guns in their hands like mafiosi, and who insisted that my mother have the photograph removed” (13).

In a symbolically loaded commemorative monument such as the immigration museum—which “has become a status symbol” for families descended from immigrants who arrived in the United States through Ellis Island (Welz 2000, 67)—the lay public takes it upon itself to legislate the exhibition of the immigrant past. Vigilant in the politics of representation, it reacts against a portrayal that may blur the distinction between the Greek Americans, often construed as model ethnics, and the Italian American underworld, an image that has been partially responsible for turning the Italians into the “symbolic villains in the American imagination” (Novak 1971, 3).4 If “any historical narrative is a particular bundle of silences” (Trouillot 1995, 27), here is an attempt at silencing the production of Greek American history at “the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives)” (26).

What is at stake when a photograph of working-class men who flaunt their newfound success—and who advertise, one might say, the magnanimity and freedoms of America by hiding the signs of labor exploitation—stirs passions as an improper sign of the past? We witness here the mapping of the past as a terrain of contested meanings. White ethnicity, a social category to which Greek America is commonly assigned by social discourses, unmistakably slips away here from its alleged cultural superficiality into an array of contested issues ranging from institutional representation to collective memory, authority, conflict, and agency. The friction over exhibiting the past directs ethnicity into the fray of heated cultural politics. It foregrounds the notion that the manner in which the past is made known to the public is not harmonious but is shaped at the intersection of competing views of identity in the present. Helen Papanikolas’s commitment to historical documentation and her authority to represent Greek America clash with the ideology of the model ethnic, the desire to construe an idealized positive image of ethnicity.5 Furthermore, how the past is made meaningful illuminates the kinds of identity that are desired today. As Jonathan Friedman (1994) observes, “the past is always practiced in the present, not because the past imposes itself but because subjects in the present fashion the past in the practice of their social identity” (141).

Who are the white ethnics here? Individuals committed to the realist representation of the past, or those determined to silence aspects of the historical record? Those who invest in exhibiting the past, or those who threaten to censor it? The public controversy over the proper display of immigrant ancestors reveals that there can be no single answer to these questions. By no means a transparent social category, white ethnicity is a construct of social practices and narratives that compete over the significance of the past in defining contemporary identity and the ways in which this identity is portrayed in the public. Of course, the idea of ethnicity as “invented, imagined, administered, and manufactured” (Bendix and Roodenburg 2000, xi) is a truism in critical scholarship, antagonizing the popular—and even sometimes academic—view of ethnicity as biologically innate and therefore immutable. Consequently, the critical responsibility becomes to investigate how pasts are made to matter in the production of ethnic meanings today: who produces usable ethnic pasts, how, and for what purposes?

In the remainder of this introduction, my task is to probe the production of usable pasts as a process crucial for identity making but also as an instrument for containing difference. I discuss this dual function in relation to white ethnicity, pointing out how the immigrant past is deployed as a resource not only to construct identity but also to sustain racial hierarchies. The discussion moves on to identify the analytical focus of my work—namely Greek America—the textual corpus that enables this analysis—popular ethnography—and my methodological locus—a metaethnography of the politics and poetics of these ethnographic texts. In the process, I map the broad contours, past and present, of Greek American popular ethnography and its relation to professional anthropology. The conclusion lays open my politics of interpretation, outlining the aims of my interventionist scholarship.

The Significance of the Past: Making Difference and Similarity

The past has emerged as a crucial social and political resource in the making of contemporary ethnicities. Ethnic pasts are politically charged because they are invariably deployed to legitimize collective belonging. Claims to identity, cultural ownership, and in the case of nationalism, territory, all build on arguments about common ancestry, heritage, tradition, and indigeneity.6 Status and prestige hinge on the possession of glorious pasts. The controversy over the right to own the Elgin Marbles—a legacy that is both Greek and global (Lowenthal 1996, 244)—for instance, rests on a logic that equates the past with biology, “heritage with lineage” (200). From the Greek perspective, if one wishes to appreciate this global heritage, one should do so in terms dictated by those who claim a pedigree from the classical past: visit Athens, not the British Museum, where they are currently exhibited. Possession of a past anchors claims to identity. Even in the most visible cases of constructed panethnicity in the United States, that is, when distinct ethnic identities submerge themselves in politically and socially expedient collectivities, the past continues to mark cultural specificity. Such was the case during the inaugural festivities of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004 at the Smithsonian Institution. In celebrating the establishment of this panethnic museum, commemorative events stressed a history of European-inflicted persecution and loss shared by all native people in the Americas; at the same time, the narrative of cultural perseverance necessitated the highly visible performance and exhibit of an astounding native cultural heterogeneity. Dances, music, dress, and crafts differentiated the Aztecs from the Cherokees and Potawatomis; the Otomis (central Mexico) from the Chippewas (Lac du Flambeau band, Lake Superior Chippewa in Wisconsin); and the Cheyenne River Lakota Akicitas (South Dakota) from the Seminoles (Florida), to mention a few. Rather than eclipsing specificity, the celebration of a common pan-Indian history brought it to the fore. Discourses on and performances of ethnic pasts bring about a dazzling proliferation of identities; their particularizing function counters the homogenizing processes of globalization.

But even as heritage and tradition communicate distinctiveness, they have also turned into venues that, paradoxically, spread global uniformity.7 Ostensibly staged to showcase ethnic particularity, heritage sites such as the genre of the ethnic festival in the United States, a commodified performance of urban ethnic tourism, tend to homogenize the global experience of ethnicity. The rhetoric of difference often produces a flattening uniformity as to what merits display and preservation. A brief survey of ethnic spectacles in the United States illustrates the unfailing predictability of what counts as a valued past in the multicultural agora. Can there be an American ethnicity without food, dances, music, costumes, or personal research into roots and family genealogy that offers recourse into an ethnic past? Polka and kalamatianos may differ in style and symbolically differentiate the Poles from the Greeks on the dancing stage, yet both function as indispensable markers of respective ethnic identities. Cultural commodification reduces ethnicities to selectively predictable expressions, applying a hue of aesthetic diversity and exoticism over routinely enacted uniformity. Belly dancers in Cairo, Istanbul, and Athens; Zorba-dance in Crete and ethnic festivals in Columbus, Ohio. Sameness is showcased as an emblem of ethnic distinctiveness for the benefit of international and domestic tourism. As the past is commodified, cultural standardization contains diversity; increasingly, local heritage circulates across national borders in a prepackaged uniformity.

Worldwide homogeneity now extends to the realm of values and ethics, a phenomenon contributing to what Michael Herzfeld (2004) calls the “global hierarchy of value” (2). Globalization in this formulation entails “the hidden presence of a logic that has seeped in everywhere but is everywhere disguised as difference, heritage, local tradition” (ibid.). Adopted globally by states, elites, and the bourgeoisie, a set of values “such as efficiency, fair play, civility, civil society, human rights, transparency, cooperation and tolerance” is normalized via an “increasingly homogeneous language of culture and ethics” (ibid.). As Bonnie Urciuoli (1998) argues, the cultural definition of the model ethnic American citizen resonates with this universalizing process. Immigrant and ethnic traditions are given premium value insofar as they contribute to what is seen as the moral betterment and socioeconomic mobility of ethnic subjects (178). “‘Family solidarity,’ ‘work ethic,’ ‘belief in education,’” she writes, “provide the moral wherewithal” that meets the culturally entrenched requirements of Americanization: in the age of multiculturalism, immigrants are classified as desirable Americans-in-the-making, and racial minorities are ethnicized on the basis of middle-class criteria, achievement, and progress. Those attributes serve as a powerful instrument of social control, given that the “worth of one’s ethnicity hang[s] in the balance: good Italian-American or low-class Sicilian? Hardworking African-American or undesirable black?” (179). Morally upright, family-centered, and successful Greek American or lazy, morally corrupt Greek immigrant (Karpathakis 1994)? Such a model, Urciuoli comments, sanctions specific forms of “acceptable difference” (1998, 178), “mak[ing] it easy to imagine that, despite categories of difference, the same embracing social truths must hold for everyone” (179).8 As American society celebrates the diversity of ethnic identities—“it has become almost a civic duty to have an ethnicity as well as to appreciate that of others,” writes Robert Wood (1998, 230)—the past is contained, and the centrifugal tendencies associated with the proliferation of specificities is managed.

The ideology of the model American ethnic sustains racial and ethnic hierarchies based on what anthropologist Micaela di Leonardo (1998) calls an ethnic report card: the positive valuation and public flaunting of those traits that are seen as leading to mobility. Such a “report card mentality,” di Leonardo writes, explains class divisions in terms of “proper and improper ethnic/racial family and economic behavior rather than by the differential incorporation of immigrant and resident populations in American capitalism’s evolving class structure” (94). The explanation of prosperity merely in terms of ethnic propensity for entrepreneurship or for hard work, for instance, denies the function of economic policies to sustain stagnation or bring about downward mobility. In this instance, ethnicity works as a mystifying process, allowing ubiquitous political and economic policies responsible for the plight of the poor to escape interrogation. In di Leonardo’s evocative phrase, it allows material processes responsible for poverty “to be hidden in plain sight” (22). In doing so, it sustains a deeply entrenched American ideology regarding the ability (and responsibility) of ethnics to pull themselves up by their own cultural bootstraps.

Culturalist explanations of mobility serve the interests of dominant classes. As Raymond Williams (1977) argues, the selective consolidation of the past into a single aspect “passed off as ‘the tradition,’ ‘the significant past’” (115–16), entails an interpretive process “within a particular hegemony” (115) in which a whole range of diverse meanings and practices is neglected, discarded, muted, or marginalized. Here, dominant traditions regulate the present; in fact, they become an essential “aspect of contemporary social and cultural organization, in the interest of the dominance of a specific class” (116). This is why every time middle-class white ethnics publicly wave their report card as an explanation of their success, scholars working on race-based poverty see in it a weapon of antiminority politics. Therefore, to write about usable white ethnic pasts means to find oneself at the center of a politicized debate that connects the past with racial and class hierarchies in the present.

The twin functions of the past as a resource for organizing ethnic identity and as a venue of containment and domination require the observer to focus on the enabling power of the past to sustain meaningful lives without losing sight of it as an “actively shaping force” (Williams 1977, 115) of hegemony that excludes alternative practices and meanings. This standpoint brings into sharp relief the notion of ethnicity as a contested field of meaning, not a uniformly shared culture or a bounded homogeneous community. I am interested here in exploring the tension between hegemonic renderings of the past and alternative cultural practices, a juxtaposition that advances the conceptualization of ethnicity beyond its present regulation as celebratory and acceptable difference. Here I am in full agreement with anthropologist Michael Fischer (1986), who frames ethnicity as an “ethical (celestial) vision that might serve to renew the self and ethnic group as well as contribute to a richer, powerfully dynamic pluralist society” (197). But the view of the past as a future-oriented ethical resource must be supplemented with a concern for cultural politics. This is to say that I wish to examine the material and political interests served in the name of the past. Specifically, I situate any claim on the past—invariably glossed as a time-honored tradition, a legacy of a work ethic, a heritage of entrepreneurial acumen, or a cultural trait of perseverance—within historically specific political economies that sustain class-, gender-, and race-based inequalities.

The present cannot be seen apart from its pasts. The regulation of ethnicity as acceptable difference in the present invites investigation of the historical processes that brought about the hegemony of white ethnicity in the first place. Now selected as celebrated signs of inclusion to the multicultural polity, the pasts of white ethnics have undergone a dramatic social and semiotic shift in relation to their transnational histories. American modernity has historically treated Old World expressive culture with suspicion, ambivalence, contempt, outright hostility, or a cautious acceptance often supplemented by strategies of containment. Immigrant customs have been objects of intersecting discourses that have constructed immigrants as primitives, exotics, savages, and inferior folk irreducibly unfit for American citizenship. Powerful racial hierarchies and relations of domination were sustained on the basis of representing immigrant cultures as embodiments of an inferior way of life. A host of immigrant activities, such as political activism directed toward social and racial justice, were excluded from American modernity. This particular immigrant engagement with social issues was fiercely persecuted and demonized as unpatriotic. What is more, bilingualism was seen as anathema and a menace to the nation. Even today’s reclaimed ethnic cuisine and dancing were at some point subjected to scorn, ridicule, and even disgust. The present celebratory packaging of the past often forgets these histories of oppression and intimidation. The glorification of selective aspects of the past is wrapped in a bundle of silences.

In view of the struggles over the place of the immigrant past in the present, it would be erroneous to treat the past as a known, fixed entity waiting to be retrieved at a moment’s notice. It would be false to approach it as a resource that merely awaits discovery by disinterested researchers: the past is a domain made rather than naturally found. What we recognize as the past comes about as a process of exclusions, displacements, and forced forgetting. It entails, in other words, an ideological construct. Attention to how the past is defined in specific social and temporal contexts enables the identification of continuities and discontinuities, but also helps recover those practices and meanings of the past that have been erased from public memory in the present. In this examination, we must take into account the strategies, interests, and investments that motivated the production of specific usable pasts. For if we take seriously the notion of the past as a dynamic and historically contingent process, we should agree with Vladimir Propp (1984) that our inquiry should center on “what happens to old folklore under new historical conditions and trace the appearance of new formations” (11). For my purposes, the inquiry into the ways in which the past is appropriated under new conditions must exhibit a strong historical component. The principal task becomes to explain why certain pasts are privileged, why some pasts resonate better than others with present conditions, and why certain pasts are relegated to the margins.

“Who Are the White Ethnics”? Whiteness, Racial Hierarchies, and Ethnic Identity

To frame my topic in relation to whiteness, might seem counterintuitive. An obvious alternative strategy is to privilege the cultural component of ethnicity at the expense of its relation to systems that organize difference in racialized terms. One might even suggest that the examination of ethnicity as culture cancels a claim to whiteness because of the normative understanding of whiteness as an invisible domain devoid of culture (Frankenberg 1993). As Pamela Perry (2001) shows, white identity is construed as a culturally empty category associated with the explicit refusal to seek “ties or allegiances to European ancestry and culture, [and having] no ‘traditions.’” To the white high school populations that she studied, “only ‘ethnic’ people had such ties to the past” (58). For these youth, ethnic traditions were not merely meaningless but undesirable as well. In fact, this construction sustains powerful hierarchies that rest on the implicit duality between whiteness as “good, controlled, rational, and cultureless, and otherness … [as] bad, out of control, irrational, and cultural” (85). “It connotes a relationship of power between those who ‘have’ culture (and are, thus, irrational and inferior) and those who claim not to (and are, thus, rational and superior)” (86).

But this should not lead to the erroneous assumption that an ethnic location necessarily distances one from whiteness. Hyphenated ethnic identities are not merely cultural signifiers; as I noted in the opening of this introduction, they are deeply entrenched in racialized categories. Popular classifications confer upon Italian Americans, Irish Americans, Polish Americans, Greek Americans, and Jewish Americans a specific racialized status because “the second part of the compound [in these identities] … always emphasize[s] whiteness” (Trouillot 1995, 133). It is precisely the incorporation of these groups into whiteness that affords them a contextual self-manipulability of identity. One could self-identify as a Greek in one context and as a white American in another.

As the scholarly project of whiteness studies has demonstrated, the whiteness of the ethnics can no longer remain unexamined, an invisible norm that evades critical scrutiny. Making its operation visible becomes a first-order analytical priority in order to reveal how it confers privilege and to disrupt its reproduction of relations of inequality. As a category historically associated with systems of domination, the whiteness component of ethnicity must be examined in order to identify practices and social discourses that contribute to its making.9

A thread within whiteness studies explains the historical transformation of the so-called new immigrants of the 1900s—a category that classified southeastern Europeans and a host of other collectives such as Syrians and Armenians as nonwhite—into the celebrated middle-class white ethnics of the 2000s. It becomes crucial for its practitioners to demonstrate how this reconfiguration in racial meaning gradually endowed white ethnics with those social privileges that were denied to people of color: entry to unions, the ability to secure loans, the right to live in certain neighborhoods, and eventually high rates of intermarriage with members of the dominant population. In a society in which complex political and social developments led to the redrawing of the boundaries of whiteness to accommodate the formerly despised immigrants, privileges accrued to those who most closely approximated its cultural, physical, and aesthetic standards.10 But the political import of whiteness studies lies in their capacity to link white ethnic empowerment with race-specific inequalities. As a center of racial and cultural normativity, whiteness does not merely represent the standard against which other categories of people were measured and evaluated. In addition, it stands for “an oppressive ideological construct that promoted in the past and maintains in the present social inequalities” (Newitz and Wray 1997, 3); as such, it is constituted by practices that consent to racial domination. Nobel laureate (1993) and distinguished professor Toni Morrison (1994a) speaks about these practices as “race talk,” the “most enduring and efficient rite of passage into American culture”: “The explicit insertion into everyday life of racial signs and symbols that have no meaning other than pressing African Americans to the lowest level of the racial hierarchy” (98). Consenting to race talk means embracing whiteness. The failure to challenge “negative appraisals of the native-born black populations” (ibid.) was the single most important variable that opened the immigrant path of opportunity. In his autobiography, labor historian Dan Georgakas (2006) affirms this position, showing how it was immigrants’ fear of stigmatization and retribution by white society—not inherent racism—that led to their passive consent to whiteness:

[I] ask[ed] my father why his bar was racially segregated. I knew he had no personal animus toward blacks, so I wanted to know why blacks were not welcomed at his bar. He replied that The Sportsman’s Bar, like all the worker bars on Jefferson Avenue, was already segregated when he arrived in the city. Greek bar owners, even if they had wanted to do so, were in no position to challenge the color line. The result would have been empty stools and tables at the least, more likely broken windows, smashed heads, and possibly worse. (263)

Whiteness studies have been effective in showing that race talk permeates social discourse even when not making explicit references to race or racism. The notion of model ethnicity, for instance, stigmatizes African Americans and works against their political interests, such as affirmative action, though it abstains from directly mentioning race. By explaining mobility on the basis of cultural values, it masks institutional practices that historically have limited or taken away opportunities from racial minorities. Anthropologist Karen Brodkin (1998) makes this point forcefully in regard to Jewish whiteness: “The construction of Jewishness as a model minority is part of a larger American racial discourse in which whiteness, to understand itself, depends upon an invented and contrasting blackness as its evil (and sometimes enviable) twin” (151). Giving “rise to a new, cultural way of discussing race” (145), ethnic pluralism eschews the burning issue of the role played by the political economy of race in structuring hierarchies. Similarly, avoiding consideration of how white ethnics commonly disassociate themselves from whiteness and instead privilege their ethnic identities fails to interrogate how white ethnics are still immersed in white privilege. As Annalee Newitz and Matt Wray (1997) make clear, “[m]aking whiteness visible to whites—exposing the discourses, the social and cultural practices, and the material conditions that cloak whiteness and hide its dominating effect—is a necessary part of any anti-racist project” (3–4).11

The “white ethnic community, since the late 1970s, is no longer a hot topic for academic papers and popular cultural accounts,” stated one of its most authoritative interpreters in the 1990s (di Leonardo 1994, 181). Its “transformed construction … remains ‘on hold.’ … [It] stands backstage, ready to reenter stage left or right on cue” (ibid.). Of course, white ethnics still possess academic cachet within whiteness studies, in which they are analyzed in terms of their historical incorporation into whiteness, as I earlier pointed out. A thread in this scholarship rightly interrogates those social structures that treated European immigrants and their descendants preferentially, while it criticizes the historical complicity of assimilated ethnics in the oppression of racial minorities. It calls attention to the political implications of early immigrant discrimination as a means of white ethnic participation in the discourse of racial victimization. Asserting “that no single group has a monopoly on being a victim” (Gallagher 1996, 349) carries political valence, as it contests race-based affirmative action policies. Construed in this manner, white ethnicity and its expressive cultures are out of vogue in departments of ethnic and racial studies presently preoccupied with alterity oppression, minority status, and marginality. But the construction of white ethnicity has been gaining momentum in popular culture, representing the intensification of an ongoing trend in numerous venues engaging with ethnicity, such as narrative and documentary film, standup comedy, television series, autobiography, fiction, ethnography, and history. No longer on hold, this production of white ethnicity has attracted increasing scholarly interest, particularly in the context of ethnic revival and roots (Jacobson 2006).

On another academic front, it was sociology, notably the work of Herbert Gans (1979), that launched white ethnicity to the forefront of research as “symbolic ethnicity,” a situational deployment of “easily expressed and felt” cultural symbols (9). Ethnicity was seen as a choice, a fleeting attachment, a nostalgic return to the immigrant past. It was discussed as a matter of sorting through the closet of one’s ancestral memorabilia, family traditions, and the available stock of ethnic manifestations to choose those aspects that most suited an individual’s needs. Symbolic ethnicity subsequently received its most systematic examination and exposition by Mary Waters (1990), and, embraced by prominent sociologists of ethnicity in the United States, most notably Richard Alba (1990), it became a powerful interpretive tool to explicate identity among middle-class, assimilated white ethnics.

The academic success of thinking of ethnicity as choice is due, in no small measure, to the capacity of its practitioners to tap into and authoritatively interpret an enduring social phenomenon: the persistence of ethnic identification among the highly assimilated descendants of European immigrants in America in the post–civil rights era. Symbolic ethnicity effectively addressed a pressing sociological question, namely why ethnicity persisted among middle-class white suburbanites. The answer privileged the notion of ethnicity as an individual’s voluntary connection with selective aspects of ethnic culture—professional organizations, parades, and festivals—that suited the need for personal fulfillment through temporary ethnic belonging. Such largely unforced belonging counteracted alienation, and its ephemeral nature freed individuals from the traditional experience of ethnicity as an all-encompassing obligation. This conceptualization marked a fundamental shift in understanding the form and function of ethnicity. It signaled a drastic departure from the classic understanding of ethnicity as a force that determines an individual’s biography (occupation, selection of spouse, place of residence, behavior). Practitioners of symbolic ethnicity reversed this model, assigning to the individual the power to exploit ethnicity, now seen as a cultural resource that could be manipulated almost at will. White ethnics, then, embodied a historical transformation in the way ethnicity was experienced and practiced. Unlike their grandparents, who followed the dictates of ancestral ways, they were endowed with the agency to script their own ethnic repertoires. Having no need of ethnicity for purposes of adaptation, generations of assimilated ethnics expressed their identities in ways quite different from those used by previous generations, this time in readily available and contextually activated ethnic symbols. Ethnicity “takes on an expressive rather than instrumental function in people’s lives,” Gans (1979, 9) suggested, framing symbolic ethnicity as a matter of enjoyment and leisure, a set of “easy and intermittent ways of expressing” identity (8). Ethnicity entailed manipulation of culture for the purposes of temporary belonging to a collective and of connecting—most often nostalgically—with the immigrant past. Individual choice was emphasized, and the significance of ethnic structures in the making of identities was severely downplayed.

Powerful academic narratives invite scholars and the wider public to think of white ethnics in terms of a polarized duality. On the one hand, these populations are known as previously stigmatized entities that eventually were granted access to whiteness; subsequently, the question of how these populations utilized white privilege to become complicit in the subordination and exclusion of nonwhites becomes of paramount importance. On the other hand, white ethnics are represented as the apotheosis of ethnic celebrationism, parading their distinct hyphenated ethnicities in public and treasuring them privately, albeit in a fleeting, superficial manner. While neither of these accounts is incorrect, one is confronted with an urgent question: is that all there is? If we uniformly hold white ethnics hostage to the notion of oppressive whites or, alternatively, treat them as innocuous ethnic caricatures, we simplify a heterogeneous constituency and neutralize its progressive politics. For, although assimilated into whiteness to a large degree, segments of these populations have not ceased to contest racial oppression or to create culturally textured worlds.12 White ethnics creatively explore their past, define their values, perform their culture, contest or reproduce whiteness, and seek connections with ancestral homelands. Still, academic writings often represent them as lacking enduring cultural moorings; they are increasingly dismissed as superficial and trivial and are relegated to the sphere of leisure and consumption. The complex web of embodied practices that organize individual action is ignored, not because of inconsequentiality in an individual’s life but because of the lack of an adequate model to accommodate their complexity and relevance.

It becomes imperative, then, to undertake a critical project that takes into account multiple facets of white ethnicity and to address their social implications in the present through an explicit politics of knowledge. This includes the interrogation of academic work that culturally caricatures and imposes an unfounded homogeneity on white ethnicity. Long overdue is a critical study of texts and practices that engages with often-cited academic topoi of white ethnicity: identity as choice, cultural superficiality, panethnicity, assimilation, and antiminority politics. Such a critical venture must undoubtedly contest white ethnic constellations that, under various guises and emerging configurations, have a negative effect on vulnerable collectives. It must expose and criticize white ethnic narratives that explicitly or implicitly contribute to the devaluation and domination of racial minorities. But such a scholarly project should not conveniently forget to identify instances in which those who have been already inscribed as whites interrogate the category from within and imagine alternative social futures for themselves and others.

White Ethnicity through the Lens of Popular Ethnography

In this work, I explore white ethnicity in a specific site of cultural production, popular ethnography. I closely analyze texts and practices whose authors, all nonacademics, deploy idioms and build on methodologies associated with the academic discourses of anthropology and folklore. For their data collection these authors depend on ethnographic methods of documentation: participant observation and interviewing. Drawing material from autoethnography and family biography is common. The authors invariably refer to and engage with anthropological and social science concepts, some in vogue, others outdated: folklore, tribe, native, ethnicity, diaspora, and heritage, for example. Their analytical concerns resonate with the ethnographic interest in local culture, transnational ties, personal testimony, and identity politics. Though interdisciplinary in scope, the body of works that I consider exhibits the ethnographic imagination to translate social realities—in this case ethnic, immigrant, or preimmigrant pasts—in terms meaningful in the present.13

None of the authors whose work I analyze are professional anthropologists or folklorists, though some style themselves ethnic historians-cum-lay-folklorists and are recognized as such in academic and professional circles. Others situate themselves as feminists, or pilgrim ethnographers. They initiate oral history projects, publish essays on immigrant folklore, curate exhibits of material culture, or even undertake fieldwork and write popularly and academically acclaimed ethnographies. Their work reaches wide-ranging audiences—both the lay public and scholars—through a wide variety of publishing venues and genres of writing—journal articles, monographs, popular essays, academic and popular books, documentaries, and museum exhibits.14

Its accessibility to wide audiences makes popular ethnography of particular analytical importance. The extensive circulation of popular accounts is in no small measure due to the saturation of the public sphere with ethnic commodities targeting niche audiences, a process that I discuss in chapter 2. Public sites of multiculturalism—including ethnic festivals or parades, children’s entertainment, museum exhibits, television programs, films, documentaries, the ethnic studies section in bookstores, as well as ethnic studies programs in universities—bring ethnicity into national consciousness. Ethnic marketers and producers are in a position to reach consumers of ethnic products in the “sacred” space of middle-class life, the entertainment center. Under these conditions, popular ethnographies become key texts through which the public encounters and acquires knowledge about ethnic and immigrant Others. They also work as venues through which audiences may reflect on practices, ideas, and images of ethnicity and race. As Anna Karpathakis and Victor Roudometof (2004, 279) report, Helen Papanikolas’s family biography Emily-George shapes how Greek immigrants in New York City explain ethnic mobility and race-based socioeconomic stratification. In the “age of ethnography” (Lambropoulos 1997, 199), market forces and the ideology of multiculturalism intersect to intensify the valence of popular ethnography about ethnicity in the American public sphere. Therefore, popular ethnographies urgently demand scholarly attention precisely because of their capacity to bring ethnicity deep into the cultural fabric of the nation.

In the broadest terms, my work examines how popular ethnography produces accounts about ethnicity in relation to immigrant pasts. I engage with this production and circulation by asking how popular ethnography intersects with the transnational and intranational movement of people, values, and ideas. I am interested in analyzing how nonprofessional ethnographers map the specific political and social geographies where cultures take root or become rerouted, are dismantled, reworked, or revived at given historical moments and under identifiable relations of power. In other words, how does popular ethnography produce ideas and traditions that have traveled across space and through time—specifically across transnational fields, through generations, within immigrant collectivities, or in the psychic and social worlds of individuals—and beyond the boundaries of ethnicity in conversation with dominant discourses, all in identifiable historical moments.

Popular Ethnography and Professional Anthropology: Flows and Circulations

Popular ethnographies are venues through which American ethnics imbue the past with value and make or unmake whiteness; they therefore lend themselves to addressing the central question of this book, namely the manner in which the production of usable pasts illuminates contours of white ethnicity. To investigate this process, I turn to a social space widely perceived as white ethnic, Greek America. A complex, variegated terrain, Greek America resists a single definition. Since its formative years, arguably in the early twentieth-century mass labor migration, Greek America has built upon a variety of pasts for different purposes. At various times, institutions or individuals have appropriated the past to accommodate both progressive working-class politics and middle-class conformism; radicalism as well as political conservatism; pioneering, boundary-crossing gender activism along with gender oppression; model ethnic success together with social failure; advocacy on behalf of minority interests alongside practices of antiminority politics; dense transnational connections with preimmigration regions of origin and Greece as well as patterns of reorientation away from the ancestral homeland.

Popular ethnography is a convenient point of entry into Greek America. The cultural archive facilitates inquiry because individuals variously connected to it have long been taking the interpretation of ethnicity into their own hands. They translate the current fascination with memory, roots, identity, and personal testimony into a rich ethnographic record. These authors regularly enjoy participation in mainstream institutions and access to academic knowledge. They exploit folklore methods to collect and analyze oral histories, to script and produce nationally circulated documentaries, to curate exhibits, and to write their own ethnographies based on long-term participant observation. Educated and attuned to the cultural politics of ethnic representation, nonprofessional ethnographers of Greek America have created a corpus of ethnographic texts—sometimes uncomplicated, often highly sophisticated, and invariably ideologically charged. The majority of these ethnographers have capitalized on the enabling conditions of multiculturalism. Their work has been supported by ethnic, national, and commercial institutions: festivals, academic and popular presses, universities, state cultural organizations, preservationist societies, community organizations, museums, and public television are among the institutional spaces that contribute to and even finance their production.

By way of introducing the complex ethnographic terrain of Greek America, I offer here the broadest possible historical survey of cross-fertilization between professional and popular ethnographies. In 1911, Henry Pratt Fairchild, a Yale-trained anthropologist, relied on social Darwinism and cultural evolutionism to deny Greek immigrants an immediate place in American modernity. His findings were confronted in the early 1920s by a self-reflexive popular anthropology generated by a Greek immigrant elite (see Anagnostou 2004a). Professional folklorist Richard Dorson (1977) argued that folk beliefs survived among Greek Americans during the nascency of multiculturalism in the mid-1950s. In contrast, popular folklorist Helen Papanikolas (1984) reached the opposite conclusion; she declared the total disappearance of Greek immigrant folk culture in post–World War II America. Feminist popular ethnographer Constance Callinicos (1990) drew on anthropological studies of gender in Greece and Greek America, including the work of noted professional ethnographer Ernest Friedl, to subvert ethnic patriarchy and reclaim tradition for Greek American women. In the process, Callinicos’s politics of transgression reproduced the evolutionist assumptions of Fairchild’s colonialist anthropology. More recently, in 2003, popular ethnographer Michael Kalafatas, an admissions officer at Brandeis University, conducted fieldwork on his ancestral island of Symi in order to examine the political economy of the sponge-diving tradition in Greece and in Greek communities in the United States and Australia. Well versed in the anthropology of Greece—carrying into the field, so to speak, Michael Herzfeld’s Poetics of Manhood (1985) and David Sutton’s Memories Cast in Stones (1998)—he advanced an allegorical reading of sponge diving.

Usable pasts are often produced through collaboration between—or juxtaposition of—professional and popular ethnographers. Anna Caraveli for instance, well known for her work on ritual laments in Greece, collaborated with professional and nonprofessional folklorists to bring to fruition “Scattered in Foreign Lands: A Greek Village in Baltimore” (1985), an exhibit on the transnational circulation of tradition. The now defunct periodical Laografia: A Journal of the International Greek Folklore Society regularly published articles on Greek folklore by both professional and popular ethnographers. Ethnographers have contested one another’s interpretations, as well. For example, professional historian Theodore Saloutos (1956) conducted a popular ethnography among repatriated immigrants, traveling throughout Greece to collect oral accounts about the experience of repatriation between 1908 and 1924. A respected scholar in the American academy, Saloutos identified but never resolved the methodological challenge of establishing the reliability of the information he collected. Dully noting the partiality of the data, he nevertheless showed no hesitation in drawing authoritative conclusions about the negative consequences of what he saw as underdevelopment in the lives of the repatriated immigrants. Yet he abstained from claiming to a total truth, “trust[ing] that future scholars” would build on his findings and “adduce new information to provide the fuller story” of the repatriated immigrants (xv). Almost half a century later, professional anthropologist Penelope Papailias (2005) cast an entirely different methodological net through the archive of immigrant repatriation to reach a conclusion contrary to that of Saloutos. In her ethnography on the poetics of historical production in Greece, she analyzed the writing, circulation, and reception of a diary written in 1951 by a certain Yiorgos Yiannis Ilias Mandas, an immigrant who ultimately returned to Greece in 1922 after a painful working-class experience in the United States. In her analysis of this account, written by a subject who might well have served as the historian’s informant, Papailias questioned Saloutos’s underdevelopment thesis. The professional historian-cum-popular ethnographer had posited underdevelopment in Greece as the source of alienation and disenchantment among repatriated immigrants. In contrast, the professional anthropologist pointed to the contingencies of history, specifically the German occupation and the Greek Civil War, as the causal factors disrupting the socially and politically meaningful life of a repatriated immigrant.

The more closely one examines the ways in which popular ethnography intersects with professional anthropology, the richer the implications about their convergences and divergences become. Take, for instance, a specific textual example, Papanikolas’s (2002) reading of Herzfeld’s (1986a) analysis of Greek folklore as a national institution. Here one witnesses how a nationalist reading of Greek identity overdetermines the popular ethnographer’s reading of the professional anthropologist, whose analysis she closely follows and generously quotes:

“Folklore studies” in other countries “played an important part” in forming a national identity “before statehood,” but “the Greek scholars were unusual in having folklore studies virtually forced on them by events” [Herzfeld (1986a, 12)]…. The Greek folklorists were intent on showing that classical Greek civilization was the foundation of European culture and that contemporary Greek culture was directly descended from ancient Greece. They set out to prove Greeks were European, not Asiatic as was commonly believed. (47)

Such a reading comes close to recognizing Herzfeld’s main thesis, namely that folklorists work ideologically and that the folk are a social construct rather than the embodiment of a national essence. But, in fact, Papanikolas reads the professional anthropologist’s analysis literally, as an objective datum that validates the idea of a racially inherent national character. This is made clear once we juxtapose Herzfeld’s point about the folkloristic construction of Greek individualism with Papanikolas’s interpretation of it:

Stressing the ethnic purity of the Greeks, she [folklorist Dora d’Istria] argued that this was revealed in a unique combination of heroism and, as the quoted passages show, individualism. (Herzfeld 1986a, 59)

The remarkable folklorist Dora d’Istria, a Romanian princess of Albanian origin, said the ethnic purity of the Greeks was “revealed in a unique combination of heroism … and individualism” (Herzfeld 1986[a], 59). (Papanikolas 2002, 49)

The two quotes are brought to bear on two divergent understandings of folklore. For Michael Herzfeld, the writings of Dora d’Istria drew selectively upon nationalist folklore and misconstrued indigenous cultural categories to present the Greek folk as unadulterated heirs of the ancient Greeks. Such a construction made d’Istria—whose work on Greek folklore gained her “Hellenic nationality by a special decree of Parliament” (55)—the ideological kin of nineteenth-century Greek nationalist folklorists. For these scholars, discovering expressions of individualism among the folk meant that this trait, which was seen as the defining attribute of Homeric heroes, had persevered as an essential element of the Greek race and, therefore, as pure national character, in spite of foreign occupations. Individualism functioned as a mirror of racial continuity that reflected the Hellenicity of the peasants (laos). Moreover, its relative abundance or lack established proximity or distance from a prized, authentic European connection. Hence Greek folklorists established a hierarchical scale of Balkan individualisms, in which the Greeks were accorded the crown of its most genuine, pure form. Because Greek individualism signaled identification with ancient Hellas, and Hellas, in turn, was “the cultural exemplar of Europe” (5), the survival of individualism underscored the Hellenic origins of European civilization. “If Greece had been the fons et origo of all Europe,” Herzfeld (1986a) writes, “then Greek folklore would enshrine the quintessence of the European spirit” (55).

In contrast to the social constructivists, Papanikolas (2002) reads Herzfeld’s quote of d’Istria as a literalist would, as evidence that Greeks are in fact individualists “to the depths of their being” (49). Ironically, an analysis that aims to expose the constructedness of national character is relied upon as evidence that substantiates that character. In this instance, the nineteenth-century folklorists become the ideological ancestors of a twentieth-century popular folklorist in Greek America. In this model, the immigrant folk are natural heirs of undiluted Hellenic culture. The identity of Greek Americans as staunch individualists, an ideological claim in Greek America that I will discuss in chapter 2, is sustained.

This close reading of a specific juncture of popular ethnography and professional anthropology gives shape to a crucial contour of white ethnicity: the power of the immigrant past to constitute ethnicity. Instead of vanishing with the dissolution of the folk Gemeinschaft, as Papanikolas has elsewhere argued (see Anagnostou 2008a), ethnicity continues to exercise a powerful grip beyond the immigrant cohort, well into the second generation. In fact, in this instance, social discourse, namely nationalism, determines an ethnic reading of anthropological scholarship. Furthermore, the popular ethnographer approaches ethnicity in the same way that a nineteenth-century Greek nationalist folklorist would approach the nation, but with one crucial difference: if early Greek folklorists produced an idealized image of the folk for the purposes of nation building, Papanikolas faced a different predicament. As we will see in chapter 3, her narratives on folkness and the degree of her connection with the vernacular were mediated by her own social proximity to ethnic traditions, which induced her to draw rigid boundaries between herself and aspects of the immigrant culture. At the same time, as I will show, her experience created an ambivalent location of identification with and disassociation from the folk, furnishing the background of a popular ethnographer’s particular investment in the making of usable pasts.

Popular Ethnography and Ethnic Roots

The quest for ethnic roots in the ancestral homeland produces yet another nexus of popular ethnography, this time in the transnational plane of Greece, America, and Greek America. In surveying the accounts of “ethnic travelers” born outside Greece—Theodore Saloutos, a social scientist; Daphne Athas, a fiction and travel writer; and Elias Kulukundis, a writer—Yiorgos Kalogeras (1998, 703) identifies a profound identity crisis that defines the encounter with the preimmigration homeland in the 1960s. This anxiety arises when the returning ethnic subject experiences the site of travel as both familiar and alien, as both known and foreign. The discourse positing Greece as the origin of the West frames the cultural literacy of the ethnic travelers. What is more, their ethnic descent qualifies them to claim the ancestral culture as authentically their own. But the actual encounter generates the crisis. Everyday social realities are alien and alienating. They pollute the Western image of Greece, accentuating the distance between the ideal and the real. The travelers have arrived too late to partake in the genius of Greece and so suffer “the anxiety of belatedness” (705). Repatriation, therefore, foregrounds a crisis of identity; it triggers a reflective process about cross-cultural connection and the representation of otherness. Greeks through filiation and Americans through affiliation, the ethnic travelers negotiate the disorienting experience of Greece as a familiar alterity largely through the lenses of ahistoricity and Orientalism. The cultural distance between Greece as a literary and an ethnographic topos is understood hierarchically. The United States is seen as the pinnacle of progress and cultural completion, whereas Greece is seen as corrupt and irredeemable, generating contempt in the observers. Greece’s own distinct modernity is not recognized by the returnees and is therefore denied. The resolution of the crisis lies in the narrative identification of the travelers with the source of affiliation, with dominant narratives about what it means to be an American. The reinvention of identity, as Kalogeras argues, “implements neither the masking of a Greek American nor the expression of a displaced American identity; it simply consolidates their sociopolitical ‘reinscription’ in US culture” (721). “It should come, then, as no surprise,” he writes, “that ethnic writers so often … perceive that their political and cultural empowerment lies in their ties to the US, rather than in other spaces, even if they are designated as pre-American mother/fatherlands” (722). But still, the quest for roots yields alternative representations of peasant life in Greece. Visiting the ancestral village in the hope of discovering clues that could explain his grandfather’s life, James Chressanthis (1982) created a popular ethnographic documentary on the experience of those who never followed their immigrant relatives to the United States. The documentary’s stark realism records the annual cycle of economic activities as well as poverty, hardship, ritual, expressive culture, and narratives about loss and separation. But unlike the ambivalent ethnic travelers, the popular ethnographer turns into an admiring witness of human beings struggling to sustain meaningful lives amid adversity. It is more this focus on the present than the effort to retrieve fragments from the past that guides the concluding humanistic message, namely the praise of the village’s human vitality.

From this broad outline, Greek America emerges as a social field crisscrossed with transnational and intranational flows of people and knowledge, one replete with contradictions, competing interpretations of ethnicity, and intellectual affinities but also with significant disjunctures. This circulation relates to all sorts of all sorts of movements: the traffic of anthropological methodologies and knowledge between the academy and the public sphere; fieldwork and the international circulation of ethnographic texts; the appropriation of the politics of feminism for the purpose of representing gender and ethnicity; American multiculturalism and the quest for ethnic roots; preimmigration traditions animated through the work of ethnics-turned-ethnographers; and the work of scholars who translate academic concepts to ethnic constituencies. Though largely produced in the United States, this cultural archive has been the result of dense transnational permutations and the permeability of boundaries between specialized professional knowledge and generalized popular interpretation. This traffic of meaning has produced a true interpretive polyphony. At any one time, Greek immigrants have been variously represented as outside the boundaries of whiteness but also at the center of it; as vanishing but also enduring folk; as successful but also failed white ethnics; and as politically invested but also apolitical subjects. The ethnographic richness of the field of Greek America makes the reading of popular ethnography a fruitful point of analytical departure.

This proliferation of popular ethnography contrasts with the embarrassing dearth of academic Greek American anthropology and folklore. Whereas in Greece a vital political function turned folklore into a socially and politically instrumental and autonomous academic discipline (Herzfeld 1986a), anthropological and folklore studies in Greek America have never enjoyed the visibility and prestige of their transnational counterparts in institutions of higher learning. The reasons for such marginality in the academy are complex. They include historically variable academic ideologies of what counts as a legitimate ethnographic subject, the lack of economic and cultural capital that would have enabled early immigrants to gain access to the university and to dominant cultural institutions, and the immigrants’ instrumentalist view of education as a means for socioeconomic mobility. Until very recently, this investment in producing “professional entrepreneurs” resulted in a historical reluctance to invest in education in the social sciences and the humanities (Kourvetaris 1989, 125).15 On the other hand, the abundance of popular ethnography on Greek America can be explained in relation to histories of controlling matters of ethnic self-representation. As a group of internal Others within the United States who were subjected to negative representation by the mainstream, including disparaging anthropological accounts, the first wave of early twentieth-century Greek immigrants to the United States deployed their own narratives about the place of their traditions vis-à-vis the nation’s history. Lacking access to institutions of higher learning, they relied on their own intellectual elite, who targeted mainstream and immigrant audiences to articulate at a popular level a theory about ethnic origins, culture, identity, and belonging. The fact that such cultural politics of controlling self-representation proved an effective tool for acceptance, power, material gains, and prestige may partially explain the tradition of popular ethnography currently in full swing in Greek America, a tradition boosted, as I mentioned earlier, by the current fascination with ethnic identity and roots.

Metaethnography as Critical Intervention: Managing the Ethnographic Field

A vexing issue remains. How does one manage this metaethnographic field? More precisely, what kind of politics must guide one’s metaethnographic reading of the vast multitude of texts and practices that vie for inclusion under the rubric of popular ethnography? For in an era of blurred genres (Geertz 1983), ethnic festivals, popular periodicals, ethnic and immigrant family biographies, autobiographies, folk dance performances, documentaries, and museum exhibits on ethnicity are all components of generalized ethnography. The producers of these ethnography-centered cultural products (self-proclaimed folklorists, oral-history collectors, community archivists, librarians turned ethnic preservationists, authors of immigrant narratives, documentary makers, or “folk” folklorists) are literally everywhere. Under these conditions, sorting out what to analyze and what to exclude from analysis becomes an acute methodological challenge. What are the criteria that will allow the displacement of some texts and the privileging of others? What are the politics of reading that will position a metaethnographer to negotiate responsibly this fuzzy, anarchic, and vastly complex field? Inherently ideological, contested, and infused with relations of power, this terrain requires methodological management, a strategic containment through an explicit politics of knowledge.16

I do not claim to read Greek American popular ethnographies from a position of disinterest. The “remaking of social analysis” (Rosaldo 1993) has made it epistemologically and politically impossible to claim a detached Archimedean point from which an omniscient scholar surveys the social field independent of power relations, material and ideological interests, and prior knowledge. Critical reflexivity demands the explicit recognition of the analyst’s subject position rather than a pretension to objectivity. It goes without saying that my current institutional location in a modern Greek studies program motivates my “choice” of Greek America as the focus of my analysis. Teaching and research in this academic field require that Greek-related topics become an indispensable component of my interest in producing and disseminating knowledge. The explicit recognition of this position helps me further sharpen the focus on my politics of knowledge. I draw my critical agenda from a body of scholarship that consistently reflects on the critical function and relevance of modern Greek studies, an academic field that operates at the institutional fringes of the American academy.

As Gregory Jusdanis (1991, 11) writes, “Disciplines like modern Greek, though marginalized at the university, need not be irrelevant…. Instead of bewailing their banishment to the fringe they can benefit from their ostracism by conducting a critique of the center.” Writing from such a position demarcates my critical vantage point. I interrogate hegemonic academic practices whose unexamined disciplinary assumptions or politics contain the range of available meanings associated with white ethnicity or, alternatively, promote its social and political trivialization. From this angle, I wish to intervene strategically and to confront influential scholarly trends in sociology and race studies that represent European ethnicities in terms of dissolution, closure, and disposability.17 My aim is to survey the complexity of Greek America and to select for analysis those texts that make accessible a set of meanings not otherwise available in dominant academic narratives about white ethnicities. While I do not shy away from interrogating dominant white ethnic narratives for their complicity in generating ahistorical accounts of diversity, I also showcase those usable pasts that challenge hegemonic interpretations in the sociology of ethnicity. In this respect, my work raises broad interpretive questions and redraws the conceptual boundaries in the study of white ethnicities. For instance, whereas scholars who privilege race as an analytical category project the weakening of collective ethnic identities, I illuminate usable pasts constructed to forge enduring group commitments. In addition, if symbolic ethnicity privileges choice in the making of ethnic identities, I demonstrate the importance of social discourses and history in determining identities. In my analysis, white ethnicity emerges as a heterogeneous social field constituted by agency and cultural determination, ambivalence and certainty, open-endedness and closure, private creativity and collective belonging—an uneven field marked by contested cultural boundaries and defined by alternative social meanings.

The organization of this book reflects my aim to intervene and problematize current academic discussions of white ethnicity. In chapter 1, I introduce the core analytical framework of this work. I discuss how a selective corpus of narrative and visual texts (professional folklore, an inchoate popular ethnography, a photograph, a newspaper editorial, and the writings of an intellectual) produces usable ethnic pasts, and I situate these texts in relation to history and social discourse. It is at this point that I demonstrate the pitfalls of analyzing ethnicity on the basis of texts alone and instead make a case for the utility of a discourse-centered, historical approach to ethnicity. I show, in other words, how texts intersect with history and discourse. To this end, I include an analysis of an inchoate popular ethnography, a text extracted from an interview that a professional folklorist conducted with members of an ethnic family. By reembedding this textual fragment in history and examining its relation to various social discourses, I show how this method helps interrogate scholarly and popular constructions of the folk and to enrich our understanding of the production of usable ethnic pasts.

In chapter 2, I continue to critically probe scholarly works that produce generalized meanings about ethnicity. I specifically take to task claims about the uniform decline of deep cultural commitments among white ethnics. Here, I turn on its head the common view of assimilation as cultural loss and examine assimilation—paradoxically—as production of ethnic particularity. For this purpose I analyze a documentary film as a narrative that assimilates Greek America into ethnic whiteness while simultaneously reproducing ethnicity as enduring collective obligation to a specific form of cultural affiliation.

In chapter 3, I further interrogate the notion of the dissolution of collective ethnicity and therefore complicate the proposition of entirely privatized white ethnic identities. Tracing the historical contour of gender construction in Greek America, I illuminate why and how two specific popular ethnographers produce competing versions of ethnic community and, therefore, polyphonies of collective Greek American belonging. Taken together, these constructions challenge the ideology of ethnicity as a homogeneous culture.

In chapter 4, I enter the political minefield of popular ethnography as cultural critique. I probe popular ethnographies that decidedly and unambiguously indict Greek America from within, leveling charges of racism and complicity in ideologies of whiteness. Sensitive to the significance of these internal critiques—but also vigilant as to the implications—I carefully discuss their politics and poetics, illuminating the consequences of white racial domination of vulnerable minorities. Within this context, I showcase an ethnic intellectual who advocates an antiracist politics based on social solidarity between white ethnics and racial minorities.

In chapters 5 and 6, I undertake a long-overdue critique of the ideology of white ethnic identity as choice. In chapter 5, I examine one popular ethnographer’s quest for roots, analyzing this ethnography of travel as a site of identity formation. I show how culture and history powerfully mediate if not partly determine this narrative construction of identity. In chapter 6, I continue this critical polemic through an alternative reading of the popular ethnography of travel, this time focusing on the historical routes of ethnic meanings. The analytical shift from roots to routes enables me to situate the current production of usable pasts historically and to place ethnicity in terms of cultural domination and power relations. I show that a historical approach to white ethnicity directs one away from the mystifying ideology of choice and toward a view of whiteness as a process of contextual negotiation and oppression, in which certain ethnic “options” become available or privileged (or, more precisely, are produced as options) while others are displaced, stigmatized, or even eliminated.