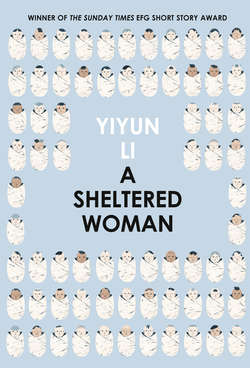

Читать книгу A Sheltered Woman - Yiyun Li - Страница 5

A Sheltered Woman

ОглавлениеThe new mother, groggy from a nap, sat at the table as though she did not grasp why she had been summoned. Perhaps she never would, Auntie Mei thought. On the place mat sat a bowl of soybean-and-pig’s-foot soup that Auntie Mei had cooked, as she had for many new mothers before this one. Many, however, was not exact. In her interviews with potential employers, Auntie Mei always gave the precise number of families she had worked for: 126 when she interviewed with her current employer, 131 babies altogether. The families’ contact information, the dates she had worked for them, their babies’ names and birthdays – these she had recorded in a palm-size notebook, which had twice fallen apart and been taped back together. Years ago, Auntie Mei had bought it at a garage sale in Moline, Illinois. She had liked the picture of flowers on the cover, purple and yellow, unmelted snow surrounding the chaste petals. She had liked the price of the notebook, too: five cents. When she handed a dime to the child with the cash box on his lap, she asked if there was another notebook she could buy, so that he would not have to give her any change; the boy looked perplexed and said no. It was greed that had made her ask, but when the memory came back – it often did when she took the notebook out of her suitcase for another interview – Auntie Mei would laugh at herself: why on earth had she wanted two notebooks, when there’s not enough life to fill one?

The mother sat still, not touching the spoon, until teardrops fell into the steaming soup.

‘Now, now,’ Auntie Mei said. She was pushing herself and the baby in a new rocking chair – back and forth, back and forth, the squeaking less noticeable than yesterday. I wonder who’s enjoying the rocking more, she said to herself: the chair, whose job is to rock until it breaks apart, or you, whose life is being rocked away? And which one of you will meet your demise first? Auntie Mei had long ago accepted that she had, despite her best intentions, become one of those people who talk to themselves when the world is not listening. At least she took care not to let the words slip out.

‘I don’t like this soup,’ said the mother, who surely had a Chinese name but had asked Auntie Mei to call her Chanel. Auntie Mei, however, called every mother Baby’s Ma, and every infant Baby. It was simple that way, one set of clients easily replaced by the next.

‘It’s not for you to like,’ Auntie Mei said. The soup had simmered all morning and had thickened to a milky white. She would never have touched it herself, but it was the best recipe for breast-feeding mothers. ‘You eat it for Baby.’

‘Why do I have to eat for him?’ Chanel said. She was skinny, though it had been only five days since the delivery.

‘Why, indeed,’ Auntie Mei said, laughing. ‘Where else do you think your milk comes from?’

‘I’m not a cow.’

I would rather you were a cow, Auntie Mei thought. But she merely threatened gently that there was always the option of formula. Auntie Mei wouldn’t mind that, but most people hired her for her expertise in taking care of newborns and breast-feeding mothers.

The young woman started to sob. Really, Auntie Mei thought, she had never seen anyone so unfit to be a mother as this little creature.

‘I think I have postpartum depression,’ Chanel said when her tears had stopped.

Some fancy term the young woman had picked up.

‘My great-grandmother hanged herself when my grandfather was three days old. People said she’d fallen under the spell of some passing ghost, but this is what I think.’ Using her iPhone as a mirror, Chanel checked her face and pressed her puffy eyelids with a finger. ‘She had postpartum depression.’

Auntie Mei stopped rocking and snuggled the infant closer. At once his head started bumping against her bosom. ‘Don’t speak nonsense,’ she said sternly.

‘I’m only explaining what postpartum depression is.’

‘Your problem is that you’re not eating. Nobody would be happy if they were in your shoes.’

‘Nobody,’ Chanel said glumly, ‘could possibly be in my shoes. Do you know what I dreamt last night?’

‘No.’

‘Take a guess.’

‘In our village, we say it’s bad luck to guess someone else’s dreams,’ Auntie Mei said. Only ghosts entered and left people’s minds freely.

‘I dreamt that I flushed Baby down the toilet.’

‘Oh. I wouldn’t have guessed that even if I’d tried.’

‘That’s the problem. Nobody knows how I feel,’ Chanel said, and started to weep again.

Auntie Mei sniffed under the child’s blanket, paying no heed to the fresh tears. ‘Baby needs a diaper change,’ she announced, knowing that, given some time, Chanel would acquiesce: a mother is a mother, even if she speaks of flushing her child down the drain.

Auntie Mei had worked as a live-in nanny for newborns and their mothers for eleven years. As a rule, she moved out of the family’s house the day a baby turned a month old, unless – though this rarely happened – she was between jobs, which was never more than a few days. Many families would have been glad to pay her extra for another week, or another month; some even offered a longer term, but Auntie Mei always declined: she worked as a first-month nanny, whose duties, toward both the mother and the infant, were different from those of a regular nanny. Once in a while, she was approached by previous employers to care for their second child. The thought of facing a child who had once been an infant in her arms led to lost sleep; she agreed only when there was no other option, and she treated the older children as though they were empty air.

Between bouts of sobbing, Chanel said she did not understand why her husband couldn’t take a few days off. The previous day he had left for Shenzhen on a business trip. ‘What right does he have to leave me alone with his son?’

Alone? Auntie Mei squinted at Baby’s eyebrows, knitted so tight that the skin in between took on a tinge of yellow. Your pa is working hard so your ma can stay home and call me nobody. The Year of the Snake, an inauspicious one to give birth in, had been slow for Auntie Mei; otherwise, she would’ve had better options. She had not liked the couple when she met them; unlike most expectant parents, they had both looked distracted, and asked few questions before offering her the position. They were about to entrust their baby to a stranger, Auntie Mei had wanted to remind them, but neither seemed worried. Perhaps they had gathered enough references? Auntie Mei did have a reputation as a gold-medal nanny. Her employers were the lucky ones, to have had a good education in China and, later, America, and to have become professionals in the Bay Area: lawyers, doctors, VCs, engineers – no matter, they still needed an experienced Chinese nanny for their American-born babies. Many families lined her up months before their babies were born.