Читать книгу Turtle Planet - Yun Rou - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWhy I Wrote This Book

Decades before I became a Daoist monk, I was born a seeker, always feeling as if I was staring at the surface of the pond, never willing to commit to a conventional life path for fear of missing out on what is really important. I’ve always sensed that we are creatures of time more than of space, and when it comes to time, we waste far too much of it. I believe we should question authority and doubt whether what we are told is true. I am wary of narratives that serve states or corporations and suspect the agendas that create those narratives.

One of those narratives that I find most disturbing tells us that animals are dumb and insensate, don’t feel pleasure or pain, and that they, and the rest of Planet Earth, are here to serve us, sacrifice for us, and do our bidding. Decades of direct experience—floating eyeball to eyeball with a one-hundred-foot blue whale, dancing with the exquisitely deadly western Australian taipan snake, cuddling a hairless dog, teaching an African Grey parrot to talk, feeding a piranha, motorcycling with a California condor flying not far off the top of my helmet—tells me that this is a pernicious lie. In fact, I very much believe, as aboriginal people have for millennia, that there is a whole universe of animal experience and consciousness that stands separate and apart from human experience and consciousness. Western science is waking up to this reality, too. Even as we continue to torture them, butcher them, and drive them to extinction, more studies show that even animals with brains quite different from our own demonstrate consciousness, feel emotions, and possess intelligence.

Included in the standard narrative that denies this fact is a hierarchy of life, from low to high, bad to good, with human beings at the top. Given how much better other animals behave than we do—we corner the market on torture, trafficking, genocide, and other equally charming behaviors—this hierarchy is as ironically twisted as a molecule of DNA. It is also a relatively recent conceit. Rock paintings, oral traditions, and archeological evidence tell us that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic pastoralists respected other living creatures more than modern humans do, giving them their ceremonial and religious due even when eating them or harnessing them as organic machines. It is only as we violent monkeys have expanded in population and slaughtered more and more of our fellow creatures to satisfy our appetites that we have formalized the distinctions between humans and other animals, even drawing upon the science of evolution to justify the maltreatment of other species of sentient beings, and, of course, different races of humans as well.

If we were honest about this hierarchy—which like our gods exists only between our ears—we would upend it and place ourselves at the bottom. Had we done so in centuries past, Genghis Khan’s generals would not have been able to train their foot soldiers to butcher innocent men, women, and children by convincing them that their victims were subhuman, and Adolf Hitler’s commanders would not have portrayed Jews as rats so as to urge their underlings to acts of shocking and irredeemable cruelty. Again, it is this false hierarchy that has allowed us all to silence our conscience in the face of factory farming and to dispense with our moral compass in the face of the wholesale rape of one beautiful, natural community after another.

Better than switching around the rungs of the ladder, I say let’s dispense with the ladder altogether. Hierarchies require judgments and judgments require distinctions, all things that Daoism, the religion in which I am a monk, regards with trepidation. Indeed, the major works of the Daoist canon all proscribe categorizations of all kinds, teaching that the minute we begin separating things one from the other, we separate them from ourselves, and that such a separation is the precise cause of the existential angst that so plagues modern culture. Only by constantly reminding ourselves that we are part of a coherent and indivisible whole, a continuum that runs from less than quarks to beyond galaxies, can we see the universe clearly and regain our sense of wonder.

The idea that we should do the right thing because doing so will benefit us has always offended me. I think it constitutes settling for a low moral level and that it sells people short. I don’t believe that rampant narcissism is our fate, and I bridle at the idea that the only way to drive people to a higher moral position is to frame it as enlightened self-interest. I believe that deep down we all care about each other and the world, even though it may not always appear that way. Accordingly, I am loath to add “what’s-in-it-for-me” material to this book. Nonetheless, the planet is careening toward total ecological collapse. If we wish to preserve the natural world as we know it, we must discard the idea that we are any better or worse than other animals, indeed that we are in any meaningful way different from them. We must stop deriding the term anthropomorphic (attributing familiar, human qualities and characteristics to animals) and face the fact that like us, animals feel pain and pleasure, bond to each other, hold the concepts of self and kin, and possess a will to live.

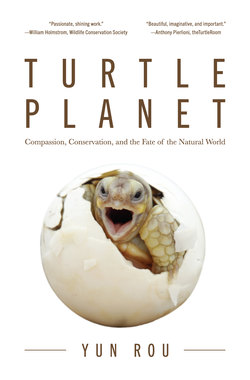

One way to effect this change is to become more sensitive and aware to the behavior of animals. Another way is to give them voice. In this book, I have done the latter for a familiar group of animals not only sorely suffering from human adventures on Earth, but also long regarded as voiceless. That group of animals is turtles. In choosing them for this literary adventure, I am hoping both to shine a light on the full spectrum of life and our own place in it, and to stimulate a global compassionate awakening.