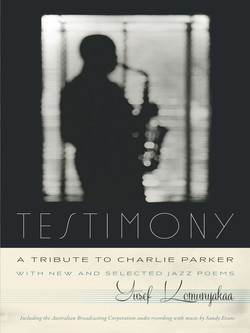

Читать книгу Testimony, A Tribute to Charlie Parker - Yusef Komunyakaa - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

Sascha Feinstein

In 1997, the same year Yusef Komunyakaa completed “Testimony,” his libretto for Charlie Parker, he flew to Chicago to perform live with a jazz sextet led by multi-reed instrumentalist John Tchicai and bassist Fred Hopkins. Released the following year on the CD Love Notes from the Madhouse, the session would go so well that Tchicai later gushed, “There might have been angels among us.” The group opened with the poem “Ode to a Drum,” the first few words a cappella, Komunyakaa’s tone like rum-soaked chocolate: “Gazelle, I killed you / for your skin’s exquisite / touch.”

Incremental accompaniment—drums at first, then bass—allowed the group members to introduce themselves. But Komunyakaa’s first words, just a grace note over two lines, also provide an introduction for the jazz poems collected here. The physicality of jazz—touching drum skins, plucking strings, pressing lips onto mouthpieces—matters a great deal to Komunyakaa, but to an even greater extent, so do the multiple implications of imagery. In this particular case, the slaughtered gazelle evokes so much complexity inherent to the instrument: sacrifice, beauty, sensuality, sound. Once touched, the nature of this skin becomes as elemental as its voice, in keeping with the heartbeat of this book’s opening poem, “Rhythm Method”: “oh yes / is a confirmation the skin / sings to hands.”

Other jazz poems by Komunyakaa expand on this imagery of body and soul. Skin provides mystery, as seen in “No-Good Blues” (“this secret song from the soil / left hidden under my skin”) and “Gerry’s Jazz” (“each secret / is buried beneath the skin”). In “February in Sydney,” a related allusion speaks to tragic realities of abuse: “A loneliness / lingers like a silver needle / under my black skin”—an image that prefigures the refrain in “Tenebrae” (“You try to beat loneliness / out of a drum”). In “Twilight Seduction,” the reference evokes sexuality and touch: “The drum / can never be a woman, / even if her name’s whispered / across skin.” And such references and experiences are never exclusive; in these poems and most others, Komunyakaa has mastered the art of braiding emotional extremes.

That ability has been evident from the start of his prestigious career. Consider, for example, poems reprinted from his first full-length collection, Copacetic—the “senseless beauty” in “Elegy for Thelonious” (similar, of course, to Monk’s tune “Ugly Beauty”), or the echo of “hard love” in “Copacetic Mingus.” Any blues artist will tell you that the most significant details in sung lyrics—the time of day, a train whistle from the hills, the flight and sound of a mockingbird—inhabit the duality of the blues, which is to say, not one meaning or another but a fusion of opposites. Joy married to longing. Departure as a form of arrival. Independence a mirror image for isolation. To categorize emotions is to betray our humanity—and every poem by Komunyakaa denies such simplicity.

The title “February in Sydney,” for example, conjures duality because of Australia’s seasonal inversion to the Northern hemisphere—summer for winter—and given that geographical displacement, the speaker in that poem naturally turns to jazz expatriates, starting with Dexter Gordon and drifting to Bud Powell, Lester “Prez” Young, Ben Webster, and Coleman Hawkins. But that displacement also speaks to the alienation of African Americans in America, an “old anger” that rekindles a memory of racism. Although the speaker tries to separate emotional and moral extremes (“I try thinking something good, / letting the precious bad / settle to the salty bottom”), jazz itself emerges as a more truthful union of the two: sound as loneliness and triumph, art as pain and epiphany.

The very first section of “Testimony” also plays upon this theme. Speaking of Parker’s formative years, Komunyakaa writes, “Maybe that’s when he first / played laughter & crying / at the same time.” By Section III, “Yardbird, he’d blow pain & glitter,” and by VI, “Charlie could be two places at once.” Again, Komunyakaa celebrates the emotional complexity of human experience by fusing opposites. Setting the poem to music, therefore, required equal expansiveness in thought and sound. In the past, Komunyakaa’s poetry has been performed to many styles of music, from contemporary classical to southern blues, but no individual poem of his has created a greater challenge for a composer.

If I came to “Testimony” and the other poems in this book with the warmth of known memory, I listened to these recordings with the joy of surprise and the deep pleasure of new friendships. From the introductory dissection of Bird tunes to the final notes from a solo alto, the compositions performed here under the leadership of the multi-talented Sandy Evans nearly overwhelm the listener with their diversity and aesthetic vitality. Evans never parrots the sound of Charlie Parker, nor does she ever opt for easy, referential gestures; instead, her compositions speak to Parker’s breadth as a musician, as well as Komunyakaa’s poetic lines, and the effect has the weighty intensity of opera. Like the libretto itself, it capitalizes on the textures of different voices and rhythms while at the same time surging forward, never lagging.

I cannot overstate the difficulty of Evans’ accomplishment, nor would I dare attempt to summarize her layered music. Tune to tune, passage to passage, we encounter tapestries of sound that play to and off one another. Call and response. Lush melody to atonality. Scripted composition to scat. Swing, bebop, church-like grooves, R & B, samba, even modern classical—the variety here both challenges and excites our ears. And forget what you think you know: No matter how familiar you may be with the infamous telegrams that Charlie Parker sent to his wife—quoted by Komunyakaa in Section X and performed as “Pree’s Funeral Song”—when you hear the actor Michael Edward-Stevens embody the language, a part of you will break.

Such artistic and emotional surprises abound on these two recordings, and the achievement highlights an obvious counter truth: It’s easy to wreck poetry with sound, and it’s equally easy to deaden swing with stilted narratives. I braced myself, for example, for the performance of Section III (“Purple Dress”) because the gorgeous imagery in those passages resists further ornamentation; with an uninspired melodic line or an insecure performer, beauty could wither. Those lines of poetry in particular already embrace the power of synesthesia; they proclaim and demonstrate how Bird “could blow / insinuation.” But hearing his known lines sung—and sung with such sensitivity by Kristen Cornwell—transforms the stanzas into something entirely fresh and memorable, an experience in keeping with the essence of jazz.

The brief quote above reminds me of Komunyakaa’s poem titled “Insinuations,” which concludes by referencing another brilliant alto saxophonist: “We said we didn’t know why / we loved walking in the rain / ’til everything disappeared, / but knew why Eric Dolphy / pried the lids off skulls.” Indeed, many of his poems that don’t appear in this book acknowledge blues and jazz musicians, if only in passing, and no reference is more intriguing than his allusion in the justly famous “My Father’s Love Letters,” where the child of a beaten mother “sometimes wanted / To slip in a reminder, how Mary Lou / Williams’ ‘Polka Dots & Moonbeams’ / Never made the swelling go down.” (As far as I know, Williams never waxed that tune, and yet the created music—that is, the artistry of Williams as recreated by Komunyakaa—seems exactly right for that poem.) Nor do mere allusions, of course, represent the full influence of jazz; if we’re to discuss the musicality of Komunyakaa’s verse, then references must give way to his own achievements in rhythm and harmony, spotlit by the ecstatic finale of “Blue Light Lounge Sutra”:

the need gotta be basic

animal need to see

& know the terror

we are made of honey

cause if you wanna dance

this boogie be ready

to let the devil use your head

for a drum.

The poem “Twilight Seduction” informs us of the “wishbone” connecting Komunyakaa to Duke Ellington—a common birth date—yet they share so much more. Just as Ellington’s creative drive seemed inexhaustible, so does Komunyakaa’s expansive and expanding outpouring of literature speak to his urgent devotion to the craft. Ellington created many works that were “beyond category,” and the same can be said of Komunyakaa. (His piece “Buddy’s Monologue,” for example, appears in The Jazz Fiction Anthology, but one could argue that it’s a lengthy prose poem or, even more forcefully, that it’s a vignette meant for the stage. In this collection, consider the innumerable ways of experiencing his poem “Changes; or, Reveries at a Window Overlooking a Country Road, with Two Women Talking Blues in the Kitchen.”) No serious historical discussion about jazz can avoid the artistry of Duke Ellington, or Charlie Parker for that matter, and no serious discussion about the poetry of our time can ignore the artistry of Yusef Komunyakaa. As made obvious by these marvelous jazz poems—a captivating cross-section that bisects his poetry through just one of so many possible vectors—his cultural contributions are indispensable.