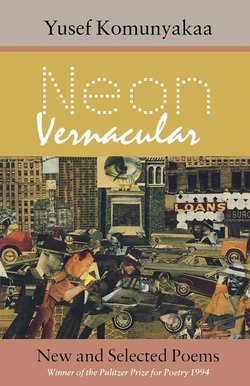

Читать книгу Neon Vernacular - Yusef Komunyakaa - Страница 8

ОглавлениеFog Galleon

Horse-headed clouds, flags

& pennants tied to black

Smokestacks in swamp mist.

From the quick green calm

Some nocturnal bird calls

Ship ahoy, ship ahoy!

I press against the taxicab

Window. I’m back here, interfaced

With a dead phosphorescence;

The whole town smells

Like the world’s oldest anger.

Scabrous residue hunkers down under

Sulfur & dioxide, waiting

For sunrise, like cargo

On a phantom ship outside Gaul.

Cool glass against my cheek

Pulls me from the black schooner

On a timeless sea—everything

Dwarfed beneath the papermill

Lights blinking behind the cloudy

Commerce of wheels, of chemicals

That turn workers into pulp

When they fall into vats

Of steamy serenity.

At the Screen Door

Just before sunlight

Burns off morning fog.

Is it her, will she know

What I’ve seen & done,

How my boots leave little grave-stone

Shapes in the wet dirt,

That I’m no longer light

On my feet, there’s a rock

In my belly? It weighs

As much as the story

Paul told me, moving ahead

Like it knows my heart.

Is this the same story

That sent him to a padded cell?

After all the men he’d killed in Korea

& on his first tour in Vietnam,

Someone tracked him down.

The Spec 4 he ordered

Into a tunnel in Cu Chi

Now waited for him behind

The screen door, a sunset

In his eyes, a dead man

Wearing his teenage son’s face.

The scream that leaped

Out of Paul’s mouth

Wasn’t his, not this decorated

Hero. The figure standing there

Wasn’t his son. Who is it

Waiting for me, a tall shadow

Unlit in the doorway, no more

Than an outline of the past?

I drop the duffle bag

& run before I know it,

Running toward her, the only one

I couldn’t have surprised,

Who’d be here at daybreak

Watching a new day stumble

Through a whiplash of grass

Like a man drunk on the rage

Of being alive.

Moonshine

Drunken laughter escapes

Behind the fence woven

With honeysuckle, up to where

I stand. Daddy’s running-buddy,

Carson, is beside him. In the time

It takes to turn & watch a woman

Tiptoe & pull a sheer blouse off

The clothesline, to see her sun-lit

Dress ride up peasant legs

Like the last image of mercy, three

Are drinking from the Mason jar.

That’s the oak we planted

The day before I left town,

As if father & son

Needed staking down to earth.

If anything could now plumb

Distance, that tree comes close,

Recounting lost friends

As they turn into mist.

The woman stands in a kitchen

Folding a man’s trousers—

Her chin tucked to hold

The cuffs straight.

I’m lonely as those storytellers

In my father’s backyard

I shall join soon. Alone

As they are, tilting back heads

To let the burning ease down.

The names of women melt

In their mouths like hot mints,

As if we didn’t know Old Man Pagget’s

Stoopdown is doctored with

Slivers of Red Devil Lye.

Salt

Lisa, Leona, Loretta?

She’s sipping a milkshake

In Woolworths, dressed in

Chiffon & fat pearls.

She looks up at me,

Grabs her purse

& pulls at the hem

Of her skirt. I want to say

I’m just here to buy

A box of Epsom salt

For my grandmama’s feet.

Lena, Lois? I feel her

Strain to not see me.

Lines are now etched

At the corners of her thin,

Pale mouth. Does she know

I know her grandfather

Rode a white horse

Through Poplas Quarters

Searching for black women,

How he killed Indians

& stole land with bribes

& fake deeds? I remember

She was seven & I was five

When she ran up to me like a cat

With a gypsy moth in its mouth

& we played doctor & house

Under the low branches of a raintree

Encircled with red rhododendrons.

We could pull back the leaves

& see grandmama ironing

At their wide window. Once

Her mother moved so close

To the yardman we thought they’d kiss.

What the children of housekeepers

& handymen knew was enough

To stop biological clocks,

& it’s hard now not to walk over

& mention how her grandmother

Killed her idiot son

& salted him down

In a wooden barrel.

Note to ebook edition readers: This poem is presented first as an illustration to show the poet’s intended arrangement of the text, then as the text of the complete left column and the complete right column.

Changes; or, Reveries at a Window Overlooking a Country Road, with Two Women Talking Blues in the Kitchen

Left column

Joe, Gus, Sham …

Even George Edward

Done gone. Done

Gone to Jesus, honey.

Doncha mean the devil,

Mary? Those Johnson boys

Were only sweet talkers

& long, tall bootleggers.

Child, now you can count

The men we usedta know

On one hand. They done

Dropped like mayflies—

Cancer, heart trouble,

Blood pressure, sugar,

You name it, Eva Mae.

Amen. Tell the truth,

Girl. I don’t know.

Maybe the world’s heavy

On their shoulders. Maybe

Too much bed hopping

& skirt chasing

Caught up with them.

God don’t like ugly.

Look at my grandson

In there, just dragged in

From God only knows where,

He high tails it home

Inbetween women troubles.

He’s nice as a new piece

Of silk. It’s a wonder

Women don’t stick to him

Like white on rice.

It’s a fast world

Out there, honey.

They go all kinda ways.

Just buried John Henry

With that old guitar

Cradled in his arms.

Over on Fourth Street

Singing ’bout hell hounds

When he dropped dead.

You heard ’bout Jack

Right? He just tilted over

In prayer meeting.

The good & the bad go

Into the same song.

How’s Hattie? She

Still uppity & half

Trying to be white?

The man went off to war

& got one of his legs

Shot off & she wanted

To divorce him for that.

Crazy as a bessy bug.

Jack wasn’t cold

In his grave before

She done up & gave all

The insurance money

To some young pigeon

Who never hit a lick

At work in his life.

He cleaned her out & left

With Donna Faye’s girl.

Honey, hush. You don’t

Say. Her sister,

Charlene, was silly

Too. Jump into bed

With anything that wore

Pants. White, black,

Chinese, crazy, or old.

Some woman in Chicago

hooked a blade into her.

Remember? Now don’t say

You done forgot Charlene.

Her face a little blurred

But she coming back now.

Loud & clear. With those

Real big, sad, gray eyes.

A natural-born hellraiser,

& loose as persimmon pie.

You said it, honey.

Miss High Yellow.

I heard she’s the reason

Frank shot down Otis Lee

Like a dog in The Blue

Moon. She was a blood-

Sucker. I hate to say this,

But she had Arthur

On a short leash too.

Your Arthur, Mary.

She was only a girl

When Arthur closed his eyes.

Thirteen at the most.

She was doing what women do

Even then. I saw them

With my own two eyes,

& promised God Almighty

I wouldn’t mention it.

But it don’t hurt

To mention it now, not

After all these years.

Right column

Heat lightning jumpstarts the slow

afternoon & a syncopated rainfall

peppers the tinroof like Philly Joe

Jones’ brushes reaching for a dusky

backbeat across the high hat. Rhythm

like cells multiplying … language &

notes made flesh. Accents & stresses,

almost sexual. Pleasure’s knot; to wrestle

the mind down to unrelenting white space,

to fill each room with spring’s contagious

changes. Words & music. “Ruby, My Dear”

turned down on the cassette player,

pulsates underneath rustic voices

waltzing out the kitchen—my grandmama

& an old friend of hers from childhood

talking B-flat blues. Time & space,

painful notes, the whole thing wrung

out of silence. Changes. Caesuras.

Nina Simone’s downhome cry echoes

theirs—Mister Backlash, Mister Backlash—

as a southern breeze herds wild, blood-

red roses along the barbed-wire fence.

There’s something in this house, maybe

those two voices & Satchmo’s gold horn,

refracting time & making the Harlem

Renaissance live inside my head.

I can hear Hughes like a river

of fingers over Willie “The Lion” Smith’s

piano, & some naked spiritual releases

a shadow in a reverie of robes & crosses.

Oriflamme & Judgment Day … undulant waves

bring in cries from Sharpeville & Soweto,

dragging up moans from shark-infested

seas as a blood moon rises. A shock

of sunlight breaks the mood & I hear

my father’s voice growing young again,

as he says, “The devil’s beating

his wife”: One side of the road’s rainy

& the other side’s sunny. Imagination—

driftwood from a spring flood, stockpiled

by Furies. Changes. Pinetop’s boogiewoogie

keys stack against each other like syllables

in tongue-tripped elegies for Lady Day

& Duke. Don’t try to make any sense

out of this; just let it take you

like Pres’s tenor & keep you human.

Voices of school girls rush & surge

through the windows, returning

with the late March wind; the same need

pushing my pen across the page.

Their dresses lyrical against the day’s

sharp edges. Dark harmonies. Bright

as lamentations behind a spasm band

from New Orleans. A throng of boys

are throwing at a bloodhound barking

near a blaze of witch hazel at the corner

of the fence. Mister Backlash.

I close my eyes & feel castanetted

fingers on the spine, slow as Monk’s

“Mysterioso”; a man can hurt for years

before words flow into a pattern

so woman-smooth, soft as a pine-scented

breeze off the river Lethe. Satori-blue

changes. Syntax. Each naked string

tied to eternity—the backbone

strung like a bass. Magnolia

blossoms fall in the thick tremble

of Mingus’s “Love Chant”; extended bars

natural as birds in trees & on powerlines

singing between the cuts—Yardbird

in the soul & soil. Boplicity

takes me to Django’s gypsy guitar

& Dunbar’s “broken tongue,” beyond

god-headed jive of the apocalypse,

& back to the old sorrow songs

where boisterous flowers still nod on their

half-broken stems. The deep rosewood

of the piano says, “Holler

if it feels good.” Perfect tension.

The mainspring of notes & extended

possibility—what falls on either side

of a word—the beat between & underneath.

Organic, cellular space. Each riff & word

a part of the whole. A groove. New changes

created. “In the Land of Obladee”

burns out the bell with flatted fifths,

a matrix of blood & language

improvised on a bebop heart

that could stop any moment

on a dime, before going back

to Hughes at the Five Spot.

Twelve bars. Coltrane leafs through

the voluminous air for some note

to save us from ourselves.

The limbo & bridge of a solo …

trying to get beyond the tragedy

of always knowing what the right hand

will do … ready to let life play me

like Candido’s drum.

Work

I won’t look at her.

My body’s been one

Solid motion from sunrise,

Leaning into the lawnmower’s

Roar through pine needles

& crabgrass. Tiger-colored

Bumblebees nudge pale blossoms

Till they sway like silent bells

Calling. But I won’t look.

Her husband’s outside Oxford,

Mississippi, bidding on miles

Of timber. I wonder if he’s buying

Faulkner’s ghost, if he might run

Into Colonel Sartoris

Along some dusty road.

Their teenage daughter & son sped off

An hour ago in a red Corvette

For the tennis courts,

& the cook, Roberta,

Only works a half day

Saturdays. This antebellum house

Looms behind oak & pine

Like a secret, as quail

Flash through branches.

I won’t look at her. Nude

On a hammock among elephant ears

& ferns, a pitcher of lemonade

Sweating like our skin.

Afternoon burns on the pool

Till everything’s blue,

Till I hear Johnny Mathis

Beside her like a whisper.

I work all the quick hooks

Of light, the same unbroken

Rhythm my father taught me

Years ago: Always give

A man a good day’s labor.

I won’t look. The engine

Pulls me like a dare.

Scent of honeysuckle

Sings black sap through mystery,

Taboo, law, creed, what kills

A fire that is its own heart

Burning open the mouth.

But I won’t look

At the insinuation of buds

Tipped with cinnabar.

I’m here, as if I never left,

Stopped in this garden,

Drawn to some Lotus-eater. Pollen

Explodes, but I only smell

Gasoline & oil on my hands,

& can’t say why there’s this bed

Of crushed narcissus

As if gods wrestled here.

Praising Dark Places

If an old board laid out in a field

Or backyard for a week,

I’d lift it up with a finger,

A tip of a stick.

Once I found a scorpion

Crimson as a hibernating crawfish

As if a rainbow edged underneath;

Centipedes & unnameable

Insects sank into loam

With a flutter. My first lesson:

Beauty can bite. I wanted

To touch scarlet pincers—

Warriors that never zapped

Their own kind, crowded into

A city cut off from the penalty

Of sunlight. The whole rotting

Determinism just an inch beneath

The soil. Into the darkness

Of opposites, like those racial

Fears of the night, I am drawn again,

To conception & birth. Roots of ivy

& farkleberry can hold a board down

To the ground. In this cellular dirt

& calligraphy of excrement,

Light is a god-headed

Law & weapon.

A Good Memory

1 Wild Fruit

I came to a bounty of black lustre

One July afternoon, & didn’t

Call my brothers. A silence

Coaxed me up into oak branches

Woodpeckers had weakened.

But they held there, braced

By a hundred years of vines

Strong & thick

Enough to hang a man.

The pulpy, sweet musk

Exploded in my mouth

As each indigo skin collapsed.

Muscadines hung in clusters,

& I forgot about jellybeans,

Honeycomb, & chocolate kisses.

I could almost walk on air

The first time I couldn’t get enough

Of something, & in that embrace

Of branches I learned the first

Secret I could keep.

2 Meat

Folk magic hoodooed us

Till the varmints didn’t taste bitter

Or wild. We boys & girls

Knew how to cut away musk glands

Behind their legs. Good

With knives, we believed

We weren’t poor. A raccoon

Would stand on its hind legs

& fight off dogs. Rabbits

Learned how to make hunters

Shoot at spiders when headlighting.

A squirrel played trickster

On the low branches

Till we were our own targets.

We garnished the animal’s

Spirit with red pepper

& basil as it cooked

With a halo of herbs

& sweet potatoes. Served

On chipped, hand-me-down

Willow-patterned plates.

We weren’t poor.

If we didn’t say

Grace, we were slapped

At the table. Sometimes

We weighed the bullet

In our hands, tossing it left

To right, wondering if it was

Worth more than the kill.

3 Breaking Ground

I told Mister Washington

You couldn’t find a white man

With his name. But after forty years

At the tung oil mill, coughing up old dust,

He only talked butter beans & okra.

He moved like a sand crab.

Born half-broken, he’d say

If I didn’t have this bad leg

I’d break ground to kingdom come.

He only stood erect behind

The plow, grunting against

The blade’s slow cut.

Sometimes he’d just rock

Back & forth, in one place,

Hardly moving an inch

Till the dirt gave away

& he stumbled a foot forward,

Humming “Amazing Grace.”

Like good & evil woven

Into each other, rutabagas

& Irish potatoes came out

Worm-eaten. His snow peas

Melted on tender stems,

Impersonating failure.

To prove that earth can heal,

He’d throw his body

Against the plow each day, pushing

Like a small man entering a big woman.

4 Soft Touch

Men came to her back door & knocked.

Food was the password. When switch engines

Stopped & boxcars changed tracks

To the sawmill, they came like Gypsies,

A red bandanna knotted at the throat,

A harmonica in the hip pocket of overalls

Thin as washed-out sky. They brought rotgut

Drought years, following some clear-cut

Sign or icon in the ambiguous

Green that led to her back porch

Like The Black Snake Blues.

They paid with yellow pencils

For crackling bread, molasses, & hunks

Of fatback. Sometimes grits & double-yolk

Eggs. Collard greens & okra. Louisianne

Coffee & chicory steamed in heavy white cups.

They sat on the swing & ate from blue

Flowered plates. Good-evil men who

Ran from something or to someone,

A thirty-year headstart on the Chicago hawk

That overtook them at Castle Rock.

She watched each one disappear over the trestle,

As if he’d turn suddenly & be her lost brother

Buddy, with bouquets of yellow pencils

In Mason jars on the kitchen windowsill.

5 Shotguns

The day after Christmas

Blackbirds lifted like a shadow

Of an oak, slow leaves

Returning to bare branches.

We followed them, a hundred

Small premeditated murders

Clustered in us like happiness.

We had the scent of girls

On our hands & in our mouths,

Moving like jackrabbits from one

Dream to the next. Brandnew

Barrels shone against the day

& stole wintery light

From trees. In the time it took

To run home & grab Daddy’s gun,

The other wing-footed boys

Stumbled from the woods.

Johnny Lee was all I heard,

A siren in the flesh,

The name of a fallen friend

In their wild throats. Only Joe

Stayed to lift Johnny’s head

Out of the ditch, rocking back

& forth. The first thing I did

Was to toss the shotgun

Into a winterberry thicket,

& didn’t know I was running

To guide the paramedics into

The dirt-green hush. We sat

In a wordless huddle outside

The operating room, till a red light

Over the door began pulsing

Like a broken vein in a skull.

6 Cousins

Figs. Plums. Stolen

Red apples were sour

When weighed against your body

In the kitchen doorway

Where late July

Shone through your flowered dress

Worn thin by a hundred washings.

Like colors & strength

Boiled out of cloth,

Some deep & tall scent

Made the daylilies cower.

Where did the wordless

Moans come from in twilit

Rooms between hunger

& panic? Those years

We fought aside each other’s hands.

Sap pulled a song

From the red-throated robin,

Drove bloodhounds mad

At the edge of a cornfield,

Split the bud down to hot colors.

I began reading you Yeats

& Dunbar, hoping for a potion

To draw the worm out of the heart.

Naked, unable or afraid,

We pulled each other back

Into our clothes.

7 Immigrants

Lured by the cobalt

Stare of blast furnaces,

They talked to the dead

& unborn. Their demons

& gods came with black rhinoceros powder

In ivory boxes with secret

Latches that opened only

Behind unlit dreams.

They came as Guissipie, Misako,

& Goldberg, their muscles tuned

To the rhythm of meathooks & washboards.

Some wore raw silk,

A vertigo of color

Under sombrous coats,

& carried weatherbeaten toys.

They touched their hair

& grinned into locked faces

Of nightriders at the A & P.

Some darker than us, we taught them

About Colored water fountains & toilets

Before they traded sisters

& daughters for weak smiles

At the fish market & icehouse.

Gypsies among pines at nightfall

With guitars & cheap wine,

Sunsets orange as Django’s

Cellophane bouquets. War

Brides spoke a few words of English,

The soil of distant lands

Still under their fingernails.

Ashes within urns. The Japanese plum

Fruitless in our moonlight.

Footprints & nightmares covered

With snow, we were way stations

Between sweatshops & heaven.

Worry beads. Talismans.

Passacaglia. Some followed

Railroads into our green clouds,

Searching for friends & sleepwalkers,

But stayed till we were them

& they were us, grafted in soil

Older than Jamestown & Osceola.

They lived in back rooms

Of stores in The Hollow,

Separated by alleyways

Leading to our back doors,

The air tasting of garlic.

Mister Cheng pointed to a mojo

High John the Conqueror & said

Ginseng. Sometimes zoot-suited

Apparitions left us talking

Pidgin Tagalog & Spanish.

We showed them fishing holes

& guitar licks. Wax pompadours

Bristled like rooster combs,

But we couldn’t stop loving them

Even after they sold us

Rotting fruit & meat,

With fingers pressed down

On the scales. We weren’t

Afraid of the cantor’s snow wolf

Shadowplayed along the wall

Embedded in shards of glass.

Some came numbered. Geyn

Tzum schvartzn yor. Echoes

Drifted up the Mississippi,

Linking us to Sacco, Vanzetti,

& Leo Frank. Sometimes they stole

Our Leadbelly & Bessie Smith,

& headed for L.A. & The Bronx,

As we watched poppies bloom

Out of season, from a needle

& a hundred sanguine threads.

8 A Trailer at the Edge of a Forest

A throng of boys whispered

About the man & his daughters,

How he’d take your five dollars

At the door. With a bull terrier

At his feet, he’d look on. Fifteen

& sixteen, Beatrice & Lysistrata

Were medicinal. Mirrors on the ceiling.

Posters of a black Jesus on a cross. Owls

& ravens could make a boy run out of his shoes.

Country & Western filtered through wisteria.

But I only found dead grass & tire tracks,

As if a monolith had stood there

A lifetime. They said the girls left quick

As katydids flickering against windowpanes.

9 White Port & Lemon Juice

At fifteen I’d buy bottles

& hide them inside a drainpipe

Behind the school

Before Friday-night football.

Nothing was as much fun

As shouldering a guard

To the ground on the snap,

& we could only be destroyed

By another boy’s speed

On the twenty-yard line.

Up the middle on two, Joe.

Eddie Earl, you hit that damn

Right tackle, & don’t let those

Cheerleaders take your eyes off

The ball. We knew the plays

But little about biology

& what we remembered about French

Was a flicker of blue lace

When the teacher crossed her legs.

Our City of Lights

Glowed when they darkened

The field at halftime

& a hundred freejack girls

Marched with red & green penlights

Fastened to their white boots

As the brass band played

“It Don’t Mean A Thing.”

They stepped so high.

The air tasted like jasmine.

We’d shower & rub

Ben-Gay into our muscles

Till the charley horses

Left. Girls would wait

Among the lustrous furniture

Of shadows, ready to

Sip white port & lemon juice.

Music from the school dance

Pulsed through our bodies

As we leaned against the brick wall:

Ernie K-Doe, Frogman

Henry, The Dixie Cups, & Little Richard.

Like echo chambers,

We’d du-wop song after song

& hold the girls in rough arms,

Not knowing they didn’t want to be

Embraced with the strength

We used against fullbacks

& tight ends on the fifty.

Sometimes they rub against us,

Preludes to failed flesh,

Trying to kiss defeat

From our eyes. The fire

Wouldn’t catch. We tried

To dodge the harvest moon

That grew red through trees,

In our Central High gold-

&-blue jackets, with perfect

Cleat marks on the skin.

10 The Woman Who Loved Yellow

Mud puppies at Grand Isle,

English on cue balls, the war

Somewhere in Southeast Asia—

That’s what we talked about

For hours. She wore a yellow blouse

& skin-tight hiphuggers,

& would read my palm

At the kitchen table: Your lifeline

Goes from here to here. Someday you’ll fall

In love & swear you’ve been hoodooed.

Mama Mary would look at us

Out of the corner of an eye,

Or frame our faces in a pot lid

She polished over & over. After she crossed

The road, I’d throw a baseball

Till my arms grew sore,

Floating toward flirtatious silhouettes.

A few days home, her truck-driver

Husband would blast a tree of mockingbirds

With his shotgun, & then take off

For Motor City or Eldorado.

She’d stand at our back door

Like a dress falling open. Sometimes

We’d go fishing at the millpond;

I kept away the snakes.

We baited hooks with crickets.

A forked willow branch

Held two bamboo poles

As we unhooked the sky. Breasts

& earlobes, every fingerprinted

Curve. When we rose, goldenrod

Left our tangled outline on the grass.

Birds on a Powerline

Mama Mary’s counting them

Again. Eleven black. A single

Red one like a drop of blood