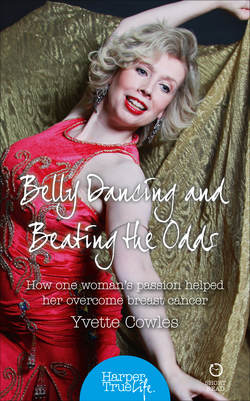

Читать книгу Belly Dancing and Beating the Odds: How one woman’s passion helped her overcome breast cancer - Yvette Cowles - Страница 8

Chapter 2 Cancer – Round One!

ОглавлениеI was leading a charmed life – and then in 1996 my luck ran out. While I was showering one day, I felt a lump. I went to the local Well Woman clinic and they thought it was a fibroadenoma, commonly known as a ‘breast mouse’. The doctor assured me that there was no real cause for concern, but given that my mother had had breast cancer, she referred me to the Royal Marsden Hospital to be checked out anyway. At that time the Breast Diagnostic Unit was housed in a portacabin.

‘Has it been here long?’ I asked the receptionist.

‘Twenty-five years,’ she replied.

I had the breast biopsy and blood tests, but again nobody seemed very concerned. And then, I received a call from one of the nurses, asking me to come back as there had been a mix-up with the tests and they needed to re-do them. My boyfriend offered to come with me but in the circumstances I couldn’t see the point. It was only a few tests. When I went back and was shown into the consulting room, I took off my top and waited for the consultant to appear. He looked puzzled when he came into the room.

‘Why have you got undressed?’

‘Because you’re re-doing the tests, aren’t you?’ He looked rather awkward.

‘We really don’t need to. We already know the results. And I’m afraid you have DCIS, or ductal carcinoma in situ. It’s the earliest possible form of breast cancer.’

I could barely register what he was saying. I had genuinely believed the nurse, but it had merely been a ruse to get me back without causing me undue alarm. Cancer. The very word made me shudder. And I’d supported my mother through breast cancer four years before and was only too aware of what she’d been through. But she had been 60 and I was only 31. The consultant went on to say that, although DCIS isn’t a life-threatening condition, if left untreated it may develop the ability to spread into the surrounding tissue and become an invasive breast cancer. For that reason I would need a lumpectomy and then, once the cells had been examined, we would discuss further options such as radiotherapy and hormone treatment.

After the appointment I called my mother, my boyfriend and a couple of close friends. I thought that by telling them it would feel more real, but I was still numbed by the news. That evening I was due to drive up with a colleague to a sales conference in Market Bosworth. In spite of my mother’s misgivings, I decided to go. I had to keep busy and not have too much time to think. Ironically though, one of the titles being presented was a book on breast cancer. During the presentation the editor reeled off a handful of statistics. ‘One in nine women will get breast cancer in their lifetime’ was one; ‘80 per cent of women who develop breast cancer are over 50’ was another.

I was devastated. ‘Why me, and why so young?’ I asked myself. I didn’t know anyone my age with cancer. Besides, I just didn’t have time to be ill. I had loads of deadlines coming up at work, not to mention a dance show and classes to prepare for. A few days after being diagnosed, I went to see the surgeon at the Royal Marsden Hospital, who told me that I would have to come in for surgery the following week. My boyfriend looked on in horror as I told the surgeon in no uncertain terms that it would be impossible as my assistant was going to be on holiday. The surgeon shook his head, ignored my protests and I was admitted a few days later.

I was really anxious about being disfigured. Before the operation, the surgeon marked the area to be removed with a black marker pen. It looked like a sizeable chunk to me. ‘Do you really need to take away that much?’ I asked him. Apparently they did. I came back from surgery heavily bandaged up and the nurses were sensitive to my concerns, only removing them when I felt ready to see the scars. There was a noticeable dent but it wasn’t so bad; I had prepared myself for worse.

It was a small ward and my fellow patients were lovely. They were different ages and at different stages of their treatment, but we all supported each other. I also had an endless stream of visitors, including my belly dance buddies. They transformed my drab little cubicle into a sequined boudoir and bought a flurry of much-needed fun and colour. Their antics really cheered me up – not to mention the rest of the ward. My close friend and dance partner, Margaret, even turned up one day carrying a huge black bin-liner, with a pink plastic arm protruding from it. With great glee she removed an inflatable man – complete with a strategically placed banana and a pair of her three-year-old’s underpants. We nicknamed him Dick Rogers and he became the ward mascot, moving from one bed to another as they became vacant during the course of the week. In fact, by the time I left, the nurses had become so attached to him that I thought it only fair to leave him in their capable hands.

During my operation the surgeons had removed some lymph nodes under my arm, to see if the cancer had spread. Thankfully, they were all clear. We then had to decide on the course of follow-up treatment. Because the cancer had been at such an early stage, there were several options open to me: radiotherapy, tamoxifen – an anti-oestrogen drug – both of the above, or neither. I opted for both, as I wanted to give myself the best possible chance of ensuring that the cancer didn’t come back.

Radiotherapy was a daily business. The treatment itself lasted only a few minutes but the whole procedure could take ages if you had to wait, or if, as happened sometimes, the equipment broke down. I was lucky that I worked in Hammersmith and could commute to work afterwards. It was fine at first, but I did get progressively more tired as the course went on. But my manager and the rest of the team were very supportive. I even managed the odd dance class, although I just went through the paces and had to be careful with my arm.

I was just grateful that the cancer had been caught at a very early stage and that I’d got away without a mastectomy and chemotherapy. I was also immensely relieved that I was being treated at the Royal Marsden. I knew I was in safe hands there, and getting the best care that the NHS could provide. And I supplemented all the medical treatment with a course in acupuncture and some spiritual healing. I felt tired and rather fragile, but listening to Arabic music and choreographing new dances in my head, plus the support and camaraderie that I got from my students and fellow dancers, really got me through a difficult time and made me determined to get better so I could perform again.

Just as importantly, the dancing helped me reconnect with my body. Like a number of women I’ve spoken to, I couldn’t help feeling that my body had let me down. How dare it do this to me! My complex about my weight, my generous bottom and other perceived defaults, was now compounded by concerns about the big dent in my breast and the ugly scar in my armpit. But allowing myself to enjoy the flowing and sensuous movements made me feel better about myself; it was a relief to know that I could still feel womanly.

Once I’d been through the treatment, I tried to put the whole cancer episode behind me. I was still taking tamoxifen, but other than that, I just needed to attend regular check-ups and have an annual mammogram. The consultant said that there was a 25–40 per cent chance of the cancer coming back, but I preferred to ignore those statistics. Back then there wasn’t a great deal of support for younger women with breast cancer and my circumstances were different from those of the older women I’d met. Rather than dwell on what I saw as an unfortunate ‘blip’, I wanted to move on and get on with my life. Up to that point, I’d felt invincible; no matter how much I punished my body, it always bounced back. I had to hope that this time would be no different.