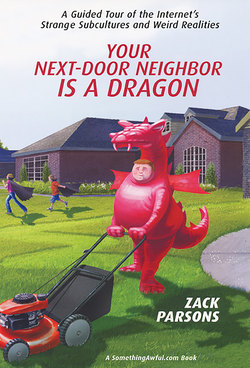

Читать книгу Your Next-Door Neighbor Is a Dragon: - Zack Parsons - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE The Matrix Retarded

ОглавлениеHe’s intelligent, but an under-achiever; alienated from his parents; has few friends. Classic case for recruitment by the Soviets.

—FBI Agent Nigan, War Games

The Internet is a slippery creature that defies description and metaphor.

Sure, the physical Internet can be defined. It can be described as routers and fiber optic lines, megabytes and gigabytes, bleeps and also bloops. That sort of description is too literal. By those rules you could claim a human is a bunch of meat and organs, but then a bucket filled with meat and organs also qualifies as human.

It is the nature, the elusive essence, of the Internet that cannot be easily categorized. What the Internet means.

Thousands of people with intellects vastly superior to mine have tried to describe the Internet. These are people with real college degrees, not the sort you buy for $49.99 from a “university” in a former Soviet state. Their degrees didn’t arrive in an envelope that smelled like salted fish and prominently featured a spelling of “master’s” that included a “k” and no vowels.

Ted Stevens, the disgraced Republican Senator from Alaska, had a bachelor’s degree in political science from UCLA. That is an undergraduate degree and probably around ten IQ points on me. The brutal Darwinism of Alaskan politics ensures no fools ever hold office in that state. Yet, even a man as robustly intellectual as Senator Stevens once infamously warned of the Internet, “It’s not a truck. It’s a series of tubes.”

Thanks?

William Gibson, one of my heroes, described the futuristic Internet of Neuromancer as a “consensual hallucination” consisting of “lines of light ranged in the nospace of the mind.” Gibson’s neon-drenched cyberpunk prose always appealed to me, but that description of the Internet sounds like a bad ride on some spinning playground equipment after huffing glue.

Gibson managed to come up with an extravagant and psychedelic version of dumb. For practical purposes the cyberspace portions of Neuromancer might as well have been a technical manual on how to send an e-mail written by Ted Stevens during a peyote-fueled vision quest. They definitely don’t get anyone any closer to understanding the reality of the Internet.

The Internet is so slippery in large part because it is vast and ever-changing. Gibson might have come closest on the third try in Neuromancer when he referred to cyberspace as something of “unthinkable complexity.”

Another nerd hero, racist horror author H. P. Lovecraft, used this technique frequently. When something was “too scary” or “too otherworldly” he would come right out and admit, “This monster is too scary and otherworldly for me to describe.” Lovecraft was dealing in impossible angles and colors from outer space.

When a writer attempts to cover the topic of the Internet, he or she is dealing with an imaginary world distributed across millions of computers and created simultaneously by hundreds of millions of people. That sounds like some impossible angles or colors from outer space to me.

Anyone who volunteers themselves as an authority on the subject of the Internet is an asshole. Don’t listen to a word they say.

The Internet is too broad; there are too many people filling it up with crap and too many rocks to turn over to ever hope to present a comprehensive picture. Descriptions become obsolescent almost immediately. There are too many tribes, cultures, subcultures, groups, and subgroups to catalog.

Nothing is more cringe-worthy for a frequent Internet user than to see their corner of the Internet described by someone from the outside. Internet subcultures can seem impenetrable to outsiders. They are esoteric, by chance or design, and their denizens communicate using culture-specific jargon and inside references that leave inquisitive outsiders baffled.

When I set out to write this book, I wanted to limit myself to subcultures I had familiarized myself with over nearly a decade of writing for Something Awful. For most of that period our Awful Link of the Day has singled out strange subcultures and weird websites for ridicule. We cruelly mocked everyone from furries yiffing in hotel rooms to miscarriage moms building photo shrines for the bloody corpses of their unborn babies.

It was a rough game we played, maybe even slightly evil, but it was a good sort of evil. Like torturing a terrorist for the location of a bomb or killing a sweet little baby kitten by giving it too many kissy-wissies. That sort of evil.

I hoped that evil experience with the Awful Link of the Day would prepare me for writing this book.

As usual, I was wrong.

Zee Chamber of Horrors

If I were forced at katana-point to offer my best attempt at a metaphor for the Internet I would have to reach for the Bible. I realize that makes me an asshole by my own rules, but trust me on this, Bible metaphors add tons of literary credibility. The Iliad was nothing but a big Jesus metaphor.

I just hope Super God doesn’t find out I’m using Regular Bible. He’s very sensitive about that sort of thing (super apostasy), but he really needs to chill out. Super Bible isn’t all that different from Regular Bible. The Psalms are written in Klingon and Super God might have gone a little overboard devoting nine Commandments to booty. Other than those two examples, and David grinding Mecha Goliath on a skateboard, and the part where Moses unleashes a plague of “dudes getting pounded by horse dicks” on Pharaoh, and Super Jesus exploding instead of being crucified, it’s all basically the same stuff.

Keeping in mind that all Internet metaphors are stillborn failures, I think that Regular Bible’s parable of that damnable apple from Genesis is about as close as you’re going to get. Snake Devil tempted Eve by telling her when she took a bite of the forbidden fruit of Knowledge her eyes would be opened and “you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” That ruined the good times for Adam and Eve in a hurry, but they knew a lot more than they did before.

Like the apple, the Internet gives each of us access to wondrous and limitless knowledge. But, the revelation of the Internet is that we discovered our vice was also limitless. Our egos and super-egos were joined by our raging ids, unleashed on a seedy world of our creation.

Adam and Eve felt shame and found the need to tie some leaves to their junk. Our forbidden fruit evidently made us shameless and gave us the knowledge to use a camera to show our junk to strangers.

This model didn’t seem so bad when the Internet first began and the knowledge was a whole lot less limitless. A bunch of nerds posting to Usenet and bulletin boards about Star Trek and boobs and Dungeons & Dragons didn’t cause society to collapse into anarchy. It was easy to see how the pros outweighed the cons.

Nerds, the perpetual outsiders and fringe characters, established themselves as the de facto rulers of the Internet. For nearly twenty years their superiority was unchallenged, but as their virtual kingdom spread it attracted new audiences and new enthusiasts. The number of Internet users grew slowly at first, but with the creation of the Web and Internet browsers those numbers began to grow exponentially.

Millions of newcomers were learning that they could establish a new identity on the Internet. Without a body to get in the way, they could literally become whoever they wanted, and as the Internet spread these identities grew in importance. Without geographic constraints like-minded individuals were able to seek out one another around the world. This allowed subcultures to flourish.

These tribes began to form on the Internet almost from the beginning, and many of the subcultures discussed in this book predate the creation of the Web. It was the Web that drove these subcultures to prominence. It made them accessible and appealing to millions. Furries and otherkin were among the first, but stranger subcultures fragmented from the originals or appeared from nothing, and narrower interests found audiences.

If you’re going to write a book that deals with questions of identity and tribalism on the Internet, sooner or later you probably need to talk to an expert.

I was three months into the process of writing the book. I had amassed a collection of websites, saved forum posts and IM conversations. I had talked to some old friends in Arizona, erotic puppeteers, conspiracy theorists, End Times believers, and various and sundry other odd individuals.

I was preparing to embark on my journey to meet with and interview as many of these characters I had come in contact with as possible. I could feel the wind at my back and the book project was developing a real sense of momentum, but I still felt a lingering doubt. It was as if there was something missing. I needed a clearer sense of direction.

It took me a few days, but I decided what I needed was the spark of insight that I could not create myself. I needed someone with a professional’s perspective. Before I learned who my weirdos were firsthand, I needed to talk to someone who knew how the Internet shapes identity and community.

With a little help from the University of Chicago humanities department, I contacted Anders Zimmerman, a graduate researcher of “cyberspace anthropology” who claimed to be working as “part of the University of Chicago.” He referred to his specific field of study as, “Inner Self Manifestation.”

Most of Anders Zimmerman’s published research involved the use of a sort of sensory immersion technique. In papers he referred to it as “The Chamber,” but its exact purpose was confusing to me and his research was light on the specifics. All I knew was that he was searching for the same sort of truth about identity that was at the core of my book.

When I spoke to Anders on the phone he sounded very excitable and very German, an over-caffeinated Freud. The mention of my book project immediately piqued his curiosity.

“Ooh, a buch, ja? I have zee reimagining chamber,” he said. “Come to meine shtudio und we can do some experiments.”

“What sort of experiments?” I asked.

“Ve re-imagine you,” he said, and then added, “In zee chamber.”

I was a bit hesitant to subject myself to “zee chamber,” a hesitancy that only re-hesitated when my taxi arrived outside a carpet outlet store in Chicago’s Hermosa neighborhood.

There are worse neighborhoods than Hermosa in Chicago, neighborhoods with more violent crimes, but this was the sort of area where some really horrible and weird shit might go down. It was the sort of area where a beloved grandma gets decapitated by a scythe or a city bus making its late-night rounds stops to pick up passengers only to find three skeletons sitting at one of the bus stops. Hermosa is the sort of neighborhood where you’re walking along and you find a baby laying on the sidewalk and you pick it up and it has your face.

The eerie desolation was nerve-wracking, but it was broad daylight. Anders’s “shtudio” was located adjacent to the carpet outlet, behind an unmarked green security door. There was an intercom next to the door with three buttons. A small placard beside the top button read SCIENC, and the other two placards were scratched out. Someone had hastily scrawled a penis and testicles in black marker across the front of the intercom.

I pressed the top button. Nothing. I pressed it again and longer.

“JA! Ja! Okay, vas?” Anders’s voice blasted from the over-amped speaker.

I leaned down to the speaker and loudly said, “I’m here to see Anders Zimmerman.”

“Ja! Shit, you don’t have to shout.”

The door buzzed and I hurried inside. It took a moment for my eyes to adjust to the dim lighting. The expansive ground floor was dusty and smelled of machine oils. Large presses or lathes of some sort were covered by plastic tarps. The overhead fluorescent lights and most of the windows were high and painted over. Thin beams of light were breaking through the crackling paint and in their shafts I’m pretty sure I could see asbestos particles.

A heavy door opened and closed somewhere far away inside the building. There was a loud click followed by a buzz as one by one the fluorescent lights switched on.

“Gutentag, Herr Parsons,” said Anders from very near to me.

I jumped, realizing the anthropologist had closed to within a few feet of me while I was staring up at the lights like a rube. He was a little shorter than me, a little older, but he had a youthful head of spiked blond hair that was thinning a little bit on top.

His facial features seemed drawn by gravity to his chin, which left a lot of empty real estate above his gray eyes and horn-rimmed glasses. He was dressed like a member of the merchant marine. He was a nightmare vision from a J. Crew catalog in a worn cable-knit turtleneck, ridiculous white canvas pants, and a pair of decaying army boots he had apparently inherited from a combat veteran.

“Hello,” I said, and shook his hand. “This is an interesting place you’ve got.”

Anders was given pause by my clicking handshake. He glanced at my gloved hand, a gift from Doctor Lian, before his internal monologue changed the subject. He surveyed the room as if just noticing it.

“Ooh, ja. This is old machine shop, leased very cheaply as long as I keep the machines. This is okay because zee chamber is in zee basement.”

Anders directed me toward another security door, this one in better repair and marked with three-dimensional chrome letters that spelled OFFI. I reluctantly followed him to the door, picturing zee basement as a rat’s maze of claustrophobic passages choked with rusty, steaming pipes and pressure gauges with needles vibrating in the red.

I calmed my nerves by reminding myself that I had braved the Twilight Zone episode that was Hermosa. I didn’t see a stray bunch of red balloons floating purposefully down the street. I didn’t have my face melted off by a pigeon. Hermosa was a way worse scene than some stupid creepy basement in a factory.

Fortunately, zee chamber in zee basement was nothing like I had imagined. We descended a perfectly normal enclosed staircase and passed through a door into an open and well-lit space. It looked more like an artist’s loft than a dank industrial basement.

It was almost the exact opposite of dank. It bordered on pleasant and warm. It was definitely clean. We were standing on cherry parquet flooring. There was a drafting table and stool and two Apple computers sitting atop two black Ikea desks. The desks were so new there were a few assembly stickers visible as we walked past.

The lighting was warm and sufficient, provided by a mixture of overhead lamps in brushed metal fixtures and standing lamps that seemed chosen to go along with a whimsical set of purple couches. I think I even heard soft music playing. Distant strains of Feist.

“Not vat you expected, ja?” Anders laughed, detecting my surprise. “Come, I show you zee chamber.”

The chamber was a separate room that resembled a racquetball court. It had three white walls, a white ceiling with starkly bright recessed lighting, and a one-way glass back wall and door. In the center of the room was a chair that looked like an ergonomic dentist’s chair. It was black and articulated, with a foot rest and padded armrests. It looked creepy, but also very comfortable. Good lumbar support.

I pressed my palms against the glass to get a better look and I realized that the white walls were not walls at all. They were made from floor-to-ceiling strips of a faintly iridescent white fabric stretched taught over a metal framework.

“What are the walls?” I asked.

“Ooh, you vill see.” Anders had taken a seat behind one of the Apple computers. “Come sit down. Vee must talk before you go into zee chamber.”

“I’m not going to sit down in there and end up on a beach talking to my space dad, am I?” I asked as I took a seat.

“No, of course not,” Anders said with complete seriousness.

He had somehow missed my insanely clever reference to the movie Contact. My opinion of him was plummeting.

“Before ve begin I must know vie you have come here to see zee chamber,” Anders said. “Vat do you vant to learn from me?”

“I want to learn why people become who they become on the Internet,” I replied.

Anders nodded.

“I want to know if the online personality is distinct from the person in the real world,” I continued. “Whether they create an idealized self or whether their environment shapes—”

“Ooh, ja, this is the key!” Anders interrupted. “Nature verzez zee nurturing. Do zee lonely become strange from seeking a sense of belonging or is it like-minded individuals they seek? Forget zee uzzer questions. Zee real question is when zee man is given a choice of identity does eet spring from zem or from zee surroundings?”

“Attraction versus actualization?” I asked.

“Ja, something link that. Und why do you think zee chamber can help you answer your questions?”

I wasn’t really sure how to answer. I wasn’t even sure about zee chamber’s intended purpose. I needed a starting point for my journey through the Internet’s subcultures and since I wasn’t going to be offering any insight I thought I could hijack some from a real expert. My search for an Internet sociologist, psychologist, or anthropologist in my area had eventually brought me to Anders Zimmerman’s fairly obscure work.

“I don’t know,” I finally said. “You claimed to be working on a diagnostic tool and I thought I could subject myself to it.”

“Nein,” Anders replied. “Not diagnosis. Experimentation. I am not a medical doctor, I am a researcher. I am observer. I do not treat.”

“So you tell me. How does the chamber work?”

“Ooh.” Anders stood. “You vant to find out, ja? First, some rules for you, Herr Parsons.”

He settled himself uncomfortably against the corner of his desk. I winced at the awkward pose. It looked as if it could lead to toilet problems.

“First and most important, zis is not a toy. Zee chamber is a complex scientific instrument and it is not an amusement. Not a joke. You said your book is funny, ja?”

“Oh, don’t worry.” I held up my hands. “My book won’t be funny at all. That’s just what the publisher thinks.”

“Ja, vell, no jokes. A joke could produce zee false result,” he scolded. “Und no getting up. Once vee start you must continue to zee end.”

“Why is that?”

“Zis is a complex process und once I start there is no shtopping. I see concern on your face, Herr Parsons. Do not fret, there is no danger to you. If you follow meine instructions nothing vill go wrong.”

Being told “there is no danger” and “nothing will go wrong” by a guy who sounds suspiciously like an Igor from a low-budget Frankenstein remake is not really reassuring. However, other than the slightly creepy chair the chamber did not look all that scary.

“Anything else?” I asked.

“Ja, you are not epileptic, richtig?”

“Nope,” I said.

“Zen vee are ready, Herr Parsons.”

Anders led me to the glass door and held it open. There was a slight pressure change when the opening door broke the seal. I could see the fabric covering the walls sway almost imperceptibly.

“Take off your shoe, but not your sock, und have a seat on zee…seat,” Anders instructed.

He watched me untie and remove my shoes and then I stepped into the room. Anders followed me in and walked me to the seat. Every movement, everything that should have made a sound, was muffled and deadened by the acoustics of the room.

I sat down in the black reclining chair. It was difficult to settle into properly, but with a little help from Anders I found the right position. At that point it became very comfortable, so comfortable I might have been tempted to nap were the room not so bright. Anders hydraulically adjusted the seat using a foot pedal on the floor and then adjusted the back so that I was facing forward and slightly up.

“Zee chair will turn slowly,” he said. “Zis, accompanied wiz everything sometimes make a person sick.”

He pressed a tightly folded paper bag into my hand.

“If you feel zee sickness, use zis,” he said.

I nodded.

“Remember, do not get up during zee process,” he said, and I replied in the affirmative.

Anders gave me one last check, adjusted the chair’s height again very slightly, and then stepped back.

“Okay, gut, you are ready,” Anders pronounced. “I will give you instructions over zee speakers. If I ask you a question you must answer immediately; do not hesitate. Hesitating can contaminate the response. Inshtinct is zee key.”

“I’ve got it,” I said, and gave him two thumbs up.

Anders walked out of zee chamber, sealing the glass door and leaving me alone with the bright whiteness. There was a mechanical thump overhead and the lights within the chamber suddenly switched off.

Faint techno music began to play from three sides. I did not recognize it, but it was driving and repetitive. It was the sort of moronically pounding music that might play over the sound system at a car show as models in bikinis posed next to an ergonomic green Frisbee on wheels. It was hypnotic twenty-first-century Jock Jams.

The music began to increase in volume, and I realized there were also speakers built into the headrest of the chair and a booming subwoofer pressed against the small of my back. The drum and bass was beginning to vibrate my insides. The sensation wasn’t entirely unpleasant. Yet.

Digital constellations of colors burst across the walls in synchronization with the music. Red and green showers of pixels exploded with each drum hit. Smaller eruptions of blue and yellow exploded into being with machine gun rapidity and tracked in glowing strips that crisscrossed from one wall to the next.

The room had become a mathematical visualization of the music, hypnotic and a little overwhelming, like the bars on a giant, psychedelic equalizer.

I presumed the effect was achieved by using some sort of projectors concealed behind the fabric and framework of the chamber’s three walls. Even knowing this, it was still impressive and a little disorienting.

The chair began to shake. For a moment I thought it was the subwoofer blasting into my spine, but as my view of the procedural fireworks began to shift I realized the chair was rotating. It swiveled on the hydraulic lift until the dark glass of the windows was on my left side, then it rotated back in the opposite direction until the glass wall was on my right.

“You vill listen to my voice,” Anders boomed from the speakers as if I had a choice. “You are entering zee Matrix.”

On cue the visualizations shifted to the green alphanumeric waterfalls popularized by Zee Matrix.

“You leave your body behind und your consciousness flows into zee digital realm. You are not any longer constrained by zee physical body. You can now be whoever it is you choose. Vatever you vant.”

The green letters and numbers faded away and were replaced by a dynamic collage of faces. They appeared to be clipped from family photos and class pictures. Most were anonymous, but I recognized Anders among the faces. And there was President George W. Bush. And…Shannon Tweed. And was that her again in a red wig?

“Now it is time to discover who you are and who you will be, Mr. Parsons!”

Anders’s delivery was overwrought and almost gleeful. He was plainly enjoying his role as the disembodied voice of the Wizard of Oz.

“The new you will begin to take shape from your unconscious and your consciousness. Your instincts will guide you. Are you ready?”

I waited for a moment to be sure he wanted a response and then I answered, “Yes!”

“Good. You are now immersed in zee stream of zee sensory data. You are beginning your journey of discovery. Look at zee images you see before you…”

The screens faded to black.

“…as each appears, speak aloud zee first word zat comes into your head. Do not hesitate. Do not think about your answer.”

What might have been simple association was complicated by the audio that began to play along with the images. As the first image appeared—a photograph of a white cat rubbing its face against the corner of a coffee table—words began to bubble out of the speakers on the chair’s headrest.

As the cat fully resolved on each of the walls I heard a steady stream of contradictory words and phrases.

“Gold,” said a computer-generated woman.

“Pickles,” said a computer-generated man.

“Red. Red. Woman. King. Zero. Champion. Guitar,” the voices babbled in my ears, switching sides and overlapping.

“Answer quickly!” Anders shouted over the main speakers.

“Cat!” I answered.

“Pumpkin. Pigeon. Book. Crease,” the voices continued, my auditory focus shifting through several bands of spoken words emerging from the speakers.

A new photograph faded in on the screens. An image of a gleaming samurai sword held in a clenched fist.

“Finger,” said the woman’s voice.

“Finger!” I blurted.

The image of the sword dissolved into a photograph of a basket full of apples.

“Crane. Shoe. Hiccup. Porridge,” the voices babbled.

“Fruit basket!” I shouted, but I had to think for a moment and resist the urge to simply parrot the words being spoken directly into my ear.

The experience would be alien to most people outside of the former Soviet Union and parts of Cambodia. Maybe a few captured American spies were subjected to something like this by the KGB, but the average person has never been led into an empty room, sat in a dentist’s chair, and asked to yell out responses to images while techno music and random words blasted in their ears.

The closest common experience might be attempting to count to a high number and being confused or losing your place when you hear other numbers. That was the sort of maddening mental failure I endured for much of the exercise. It was a constant struggle for my brain to react to the images independently of my ears. I got the hang of it after several pictures, but as it progressed I realized my defense mechanism was simply naming what I was seeing in the photo.

“Very good,” Anders announced, even though I was feeling stressed out by the exercise. “Take a moment to regain zee composure. Listen to zee music und relax. Vee vill continue to zee next phase once you tell me you are ready.”

The digital fireworks returned and the music grew a bit louder. The chair continued to swivel from side to side. I had to admit, the sensory overload was becoming slightly nauseating.

I fought through the ache in the pit of my stomach and announced my readiness.

“Excellent. You are doing vell, Mr. Parsons.”

The music softened a bit as the screens once again faded to black.

“Now vee vill be reversing things a bit,” Anders said. “I am going to ask you a series of questions. You vill see images on zee screens, but you are to respond only to my questions. Zer is no right or een-correct answer to zees questions. Answer however you like and recall your goal is to manifest your inner self.”

“Are you ready?” he asked.

“Ja!” I replied.

“Vee begin…now!”

Images began to flash rapid-fire across the screens. It was an accelerated version of the earlier collage of faces, but covering a much broader spectrum of subjects. It was an onslaught.

Mundane images, violent images, strange images, and pornographic images exploded in complete disharmony across three walls of the chamber. One moment a black-and-white photograph of a ranch house appeared and a moment later it was covered by a photograph of genital herpes from a medical textbook. A moment later the herpes disappeared behind an image of kids cheering on a roller coaster.

I reeled from the imagery. I was being deluged with disorienting optical static even more intrusive than the words being shouted in my ears during the first exercise.

“Vat is your favorite color?”

The Taj Mahal at sunset. A gauzy glamour photo of three children with Down syndrome standing in front of a Christmas tree.

“Vermilion!” I shouted.

“Name your best quality,” Anders instructed.

A stone arrowhead. A fat woman’s cleavage. An F-117 Stealth Fighter parked at an air show. The world was spinning. An insane whirling kaleidoscope of colors and pictures.

“My punctuality!” I shouted.

“Vat is your greatest flaw?” Anders asked.

A recreational Jeep stuck in a ditch. A baseball pitching machine. Dolphins leaping out of the water in unison. I could no longer tell what was actually being projected on the screen and what shapes my brain was creating out of the rippling, turning bands of color.

“Ahhh fuck I hate…late women,” I answered.

A tombstone. A collectible motorcycle. Question after question. Bile crept into my throat. My legs shook involuntarily.

I tried closing my eyes, but an unseen camera in the room betrayed my tactic. Anders warned me to keep my eyes open and chided me about joking with my answers.

A rabbit chewing on a wood chip. A woman nude except for a headband. My friend from childhood?

The questions continued. It felt as if I was drowning in the sensations of the room. Sweat coursed down my temples and over my forehead. I was constricted, almost breathless.

“If you could have two of anything, vat vould you vant?”

A Brazilian football player catching a ball with his face.

“Vaginas,” I answered with a gasp. “Vaginas on my…hands.”

A T-72 tank model kit.

“What is zee name you call yourself?”

The strange way Anders phrased the question had to be intentional.

“Vaginahands?”

“Who is—”

Anders was interrupted by a ringing telephone.

“Excuse me, Herr Parsons,” he said.

The images abruptly faded to a deep gray static. A soothing ocean of nothing. The room was dark again. My pupils were so blown out I could barely make out my hands resting on the arms of the chair.

I heard a pop of audio, as if Anders had turned off the intercom. He had only switched channels. When he answered the phone, his words were broadcast through the chair’s headrest.

“Hello,” Anders answered.

“Becca, I can’t talk now,” he said in a perfectly normal Midwestern accent. “No, we can talk about this tonight. I’m with somebody.”

There was a pause as the person on the other end, presumably “Becca,” said something to Anders. I took a moment to absorb this new information. Anders Zimmerman was a fraud on at least one level. He sounded like he was from Des Moines, not Dresden.

I realized that if that asshole was faking a German accent to earn kooky science credibility, well, it had worked. But the proverbial jig was proverbially up.

“It’s not Megan,” Anders said with evident anger. “She’s gone and I haven’t—”

Becca shouted something so loud it was audible (though unintelligible) in the headrest speakers.

“No, no! No, sweetheart, it’s just some jerkoff who found me through U of C. I don’t—”

Ol’ Vaginahands had heard enough. It was a struggle to get out of the slowly rotating seat, but with a grunt of effort I flopped out on the side.

It was difficult to navigate by the stroboscopic flash of the digital collage on the wall screens and I tangled myself up on the seat’s hydraulics. I spun uncertainly and nearly fell back on my knees. At last, I was able to steady myself by looking at the distorted reflections in the glass back wall. It was much darker than the other three walls.

I shuffled my way to the back wall. With one hand resting on the glass I slowly worked my way to the door I remembered in the middle. My fingers found the latch and I opened the door with a pressurized thump and a rush of air.

Anders was still on the phone when I emerged from zee chamber. He looked up with surprise.

“Herr Parsons, I varned you not to get up!” he exclaimed, setting aside his cordless phone.

I blinked away the stars from the lights. My head was swimming with the aftereffects of the digital torture and I still wasn’t steady on my feet, but I was through with the bullshit. I was even content to leave without confronting Anders, but he stepped between me and the door to the stairwell.

“You have not yet manifested your inner self,” he said.

Anders was wrong about that. His stupid light show hadn’t answered my questions, but he had unwittingly told me exactly what I needed to hear. Thanks to his bizarre attempt to scam me, I could see Zee Retarded Matrix. I didn’t cram years of human understanding or journalism school into an hour in a computerized funhouse, but I did manifest my inner self.

I was an asshole.

I gave Anders a shove. One-handed. Not enough to knock him over, I’m not a particularly tough or strong person, but it was forceful enough to make him take a step back. He looked at me with surprise.

And let me go.

A Special Delivery

Strange as my visit was to Anders Zimmerman’s amazing Technicolor dream chamber, there was an even stranger epilogue.

About a week after I discovered my inner self, I was sitting at my desk working on an article for Something Awful. The doorbell rang and I answered to find a FedEx deliveryman. I signed for a standard FedEx shipping envelope.

I tore open the perforated tab and a single playing card spilled out into my hand. It was the ace of spades—the death card.

On the back was a message written in fine-tipped black marker.

“I see you when you’re sleeping.”

It was signed with the initial “A” printed in a circle.

I called Anders and received his voice mail. The message I left for him was, well, let’s just say it was intemperate. I promised to do things to his face that are a crime just to contemplate. I remember at the end of the call I told him I would jump up and down on him until his guts popped out of the top of his head like a tube of toothpaste.

Anders never returned the call, which was probably for the best. He wasn’t the sender of the mysterious message.

By the time I learned the true identity of the sender it was much too late.