Читать книгу Still Life - Zoeë Wicomb - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I

ОглавлениеI do not think this a task that I could, or even should, take on. The responsibility is simply too heavy to shoulder; besides, the obligation is of a dubious nature. Thus I try to keep my head averted from these powdery phantoms that stir and falter in the dark. But they remain, pleading wordlessly – or so it seems.

What kind of makeshift shelter is this? Wind rattles the reeds that pass for rafters and the corroded sheets of corrugated iron lift creakily and fall, lift and fall, so that shafts of light snap at the spectral figures flailing, writhing in their am-dram poses. I resist the use of a torch, but cannot stop myself from peering inside when the light allows. Which is taken for encouragement – they are not as comatose as they once appeared to be – so that their rustling sounds rise above the wind sigh. I cannot tell how many there are, but there is no mistaking that these feverish forms are fixed on coming into being, on finding language, on making their demands on me.

One of them whispers: It is not so unusual, neither novel nor extraordinary, not so much to ask; it has been done before.

I listen in silence to their strange and various accents, to the voices growing louder, cacophonous in their clamour to be heard. The slight, bent form in the corner rocks to and fro, declaims in a dazed, rasping voice so that I catch only fragments: Poppy, or charms … one short sleep past … the round earth’s corners. Over and over, growing fainter until it fades away.

After all, says the larger, older woman, the boldest, the most insistent of the lot, we do not have to be invented, no need to think of yourself as a god, a creator. Good Christian souls, all of us, prematurely cut off but, of course, blessed with eternal life all the same, so only a small matter of giving us another chance, of allowing us our fair share of years.

She stumbles to her knees, strains forward, and if her form is wobbly, a strong, vegetal whiff of desire rises from it, a greed for life, for recovering time – those bitter years of duress, salted bondage and subjugation gone for good, finished and done with. Her palms scrape, slap against each other as she reaches for the possibilities of a new life, a new century, a world shaken up in so many ways, so much more forgiving than the unjust, punitive world of yore. This is exactly what she had dreamt of, what she craves – a fresh start, her just deserts. She will not be held back.

Looks like some kind of punishment, this eternal life bestowed by your God, I venture, but there is no uptake. They are not interested in argument; their focus is on filling out, on coming into being, and they are not above pleading.

The woman speaks as if I had not spoken. Oh, we have our different desires, as you must know, she says, but we are bound together all the same. The bond of love.

Love! I roll my eyes, squirm.

The men seem more circumspect; they too shrink visibly at the word, which keeps them quiet for a while. I ignore the young man whose hand is up like a schoolboy’s waiting for permission to speak. Bonded indeed. As if I’ve not heard that kind of talk before, the justifying cant of politicians and ordinary folk alike, even as they pursue their selfish interests.

What do I know beyond what the history books say? Does the woman think me omniscient? Her words leave me impotent, tongue-tied. Frankly, I have no idea what to do; I do not know how to proceed. I who have freely admitted failure, who have given up on the business of writing, who have comforted myself with the promise of carefree, indolent days, albeit under dark northern skies. Who would not rather watch clouds tumbling through the heavens? Slouching in a deck chair with a woollen rug (from childhood, the dun tartan of overnight train journeys) over her knees, cherishing the slivers of stingy sunlight? For fighting slow time, there is a garden in which to hoe, to shake earth free from the roots of weeds, and watch worms writhe into the humus. I would rather drum my fingers and wait for forget-me-nots to spread into a blue haze and tulip spears to unfold their slow promise of red, and battle with indomitable slugs.

Why should I return to the fray and struggle with the stories of these creatures? Why invite judgment of my abilities? Whilst these figures imagine a new era of millennial harmony, it is I who will have to rise to unexpected challenges and fend off the slurs reserved for upstarts of my ilk.

I note that the young man, giving up, has dropped his supplicating arm, but no such luck with the woman. Come, come, she breathes, prodding a finger at her breastbone, Mary here, Mary Prince.

As if I don’t know her name. Her voice grows stronger as she remonstrates: Get over yourself. It’s not about you at all. So very little we ask of you, nothing more than allowing us to be, setting us free. She shakes her head as I grimace at the word. You don’t like my language? the way I speak? Well, that’s nothing new to me; I’m used to my island’s tropical tongue being mocked. But look, you’re free to improvise, to correct, and use your own fancy words. Here we are, emaciated, and …

Whilst she falters, the young man slips in: In the words of another poet, dusted to mildew.

Oh shush, Mary says impatiently, and rudely points at me. It is you, oh yes, there is no question, it is you who have sought us out, peered at us through the cracks. Look, there is room for you to dress us up or down, but we want out, we’ve had enough of being trapped in this derelict pondok of history.

She stretches her arms up, slowly, testing as it were their materiality, their flexibility, then rises to one knee, placing a foot on the ground. Nothing can hold us back now, she declares. Think of us as ready-mades, and that is an advantage not to be sniffed at. So there you are: a shoulder to the writing wheel, a pen filled with black ink, and Bob’s your uncle.

Unbelievable. Where does the woman, barely risen from dust and mildew, get her confidence? Clearly, she is one to be watched, one not past elbowing the others out of the way and taking over. If only she knew that I could house them in little more than another pondok – of another order, yes, but the house of fiction within my means, with its rusted tin roof, may be no less leaky.

The older man, the pale, slight poet rocking to and fro, should know better, should know that having a ready-made subject does not guarantee a work.

If they are my responsibility, I have no idea how to proceed. If I stamp my feet in frustration, insist that I will not be bullied by phantoms, it is also the case that my idyll of battling with garden slugs and nursing tulips slain by vernal gusts grows dimmer by the second. Foolish, foolish me. I should have crept away, not have peeped, listened in, or spoken. Before I can say humpty-dumpty I find myself tied to this desk, a Procrustean bed, with no more than a bag of sweets for comfort. Beside me a mound of wrappers grows. No question of kidding myself that an epiphany will rise out of the crackle of cellophane and foil; rather, an unsightly crop of spots has appeared across my forehead. Sweet Jesus, am I to be propelled backwards, awkward and pimply, into adolescence? Whilst these my subjects bully and bluster their way out of history?

Let me start with the poet in the corner, muttering about poppies and charms, he of the eternally boyish looks and slight frame, a pair of crutches tucked neatly under his arm as he rises to his knees. Pure trouble, even as he averts his eyes in modesty, so that I push back my chair and grope for the stash of fortifying chocolate sweeties in the drawer.

I favour the dark variety, at least seventy per cent cocoa solids, ones filled with keen, candied ginger, sharp enough to kick-start things. It is also, if not mainly, for the lovely silver and gold foil wrappings – the luxurious treasures of a child of the bundu – that I buy them at all. Perhaps I ought to drop the actual sweet straight into the bin, given that I eat only out of the habit of husbanding resources, of waste-not-want-not frugality. But as far as achievements go, that would not be so staggering, so why deprive myself? It is the wrapper that brings lasting joy and makes the mouth water. The extra, outer cover of cellophane is for delaying gratification; for holding up to the light, for seeing the world momentarily through pink, blue or green before scrunching it up. Then the quarry: silver or gold foil, metallic paper I hold down with the left thumb, firmly rub with the right index finger until the rectangle is returned to an original, pristine state. Ta-dah! Voilà! Ecco! There! Now the perfectly smooth foil can be folded meticulously into a solid strip, a band to be wrapped around my finger like a wedding ring. When I tire of touching of smoothing of tightening of stroking, the band drops on to my desk where it leisurely lets go, uncoils somewhat, but holds on to the memory of having once been a perfect circle. There! The rings settle into the intimacy of a growing pile on my left, may even hook into each other. Call it procrastination, but it does no harm; in my book this counts as an achievement, could be the precursor to who knows what.

I ignore the hm-hm of Mary clearing her throat, her scornful hiss of Sugar!, ignore the impatient shuffles and mutters of the others. Being a dab hand at foil rings is of no interest to them. Better than sitting on my hands, I reckon, for it is a start of sorts. Look, I am at my desk, once more like the child learning to form her letters, filling her page with wobbly ABCS. And here is material proof of my presence: strips of curved foil each bearing the shape of a band, a ring, something accomplished with my hands. Perhaps I should start by filling a page with his name, the poet’s, which would be to name the project. Then wait for the letters to stir, in the manner of the mound on my desk, coils of silver foil easing their shoulders, unfurling their sugary history.

The woman stirs. My history is one of salt, she hisses; as for sugar plantations … I wave her into silence with new, gingered strength, but she leans forward, elbow comfortably on her raised knee. Just start at the beginning, she pleads, no need for anything fancy. Our stories are connected, so I’ll fill in the gaps.

A history, then, of our man the poet, who binds together these phantom creatures and in whose interest they have gathered here. ‘His story’, as we feminists of the 1970s called it, scorning etymology, dismissing the history of the word, and not caring about being thought ignorant of Latin. Years before that, when the nineteenth century was new, our young poet, the punctilious scholar busily copying documents in Edinburgh’s Old General Register House, would have bristled with irritation at such sloppy ways, but och see, if he can’t mellow over the centuries what would be the point of living on and on and on? Even if it is only in what he still fondly thinks of as the colony, whereas in his beloved Scotland he has long since been forgotten. (In truth, he never made much of a mark even when he lived there; or rather, such mark as he had made in Blackwood’s’ treacherous literary circles is best forgotten.) His story it may be, but all will be thrown up in the air as others throw in their tuppenny’s worth, as events arrive in who knows which way, out of order, not unlike my shiny sweet wrappers hooking up higgledy-piggledy with others, and how should I presume the wherewithal to straighten things out?

Strange, thinking of him now as my subject. (How a queen must clutch her throat and shudder at the thought of subjects, even as she goes on to tilt her head, and wave, and pat her pearls and smile graciously, regally, at those very entities.) Be gracious, I upbraid myself, sans pearls. So I salute my subject, the poet with weak lungs, and tilt my head at the keyboard. Now, to lunge into his story, the story of a dead white man. Of which there are so very many, quite enough really, and there’s the rub, but Mary, ever the meddler, interrupts in a voice grown stronger that that can be dealt with later; indeed, that the man would agree to deal with the problem himself. He wants out as much as I do, she says confidently. Then louder, proudly: He is, has always been, the Father of South African poetry.

I note the twitch as he raises his head, holds it as if listening for an air to creep upon the waters of time. And I have to lean in to hear as he rasps, But … not … known … in Scotland.

Oh yes, unmistakably the voice of one who has never wanted for ambition, who became even more fired up once he came to believe in a brave new world free of slavery. No need to fret, Mary soothes, addressing the man, helping him up. We’re here for you. Over her shoulder she says, Together we’ll turn the story into a devil-may-care whistling of women, and she winks at me. Which I find only mildly encouraging.

History/His story: anachronistic it may be, and now mellowed, but all the same, the poet senses a way out in the insertion of that superfluous ‘s’ in hisstory. He is not ungrateful. Mary and the young man have kindly, heroically taken on the project of restoring him to the wider world, by which he means Great Britain, but where after all would they have been without him? Indebted, they are his, have in a sense, in their different ways, been made by him, and it is his story, one of which he has every reason to be proud, so there must be a way of wading boldly through the centuries to arrive at it, shape it and present it to the world.

A memorable start it was too. No schoolboy could forget the auspicious year of his birth. Even there on the Scottish Borders, on the banks of the Tweed, all the way across the Cheviots, the tenor of his life was set by the whiff of liberty, equality, fraternity that drifted over from Europe, settling like a fine mist around his cradle. Seventeen eighty-nine, the year of revolution, a year in which to foresee the end of slavery and fine-tune the limited enlightenment of his land, usher it into the bright light of liberty for all. History, his story, made, then unmade and now to be remade, and he sees that in this woman’s reluctant hands it will become inseparable from theirs, the stories of the other ghostly figures in whose making he had had a hand; and thus, with these allies by his side, a story to be packaged anew, cast in yet another light.

Inseparable for sure, Mary interjects in a voice grown firm. She hauls the young man from the shadows into which he has retreated and presents him, as if for inspection, whilst she speechifies as if I’m not there. We, in our love and gratitude, have founded this project and assigned to this available writer the task of restoring Mr P, a great poet and humanitarian, Father of South African Poetry, to the wider world. Holding her collaborator firmly by the hand she asks if 1789 is not also the year of Sara Baartman’s birth. Like Mr P, her remains, too, have been taken home to the Eastern Cape. Should there not be room in their project for that unfortunate South African woman, rudely displayed on European stages? She no doubt would want to account for herself.

But the young man shakes his head firmly. Mr P, he says, would certainly have rescued poor Saartjie in London, clothed her, yes, but she came later, once he was dead. Besides, she has no need of us. Back home she has been remade in many forms, fought over, tossed hither and thither, clothed and unclothed as in a French farce. What that unfortunate woman needs more than anything is to be left alone, to rest in her warm Eastern Cape grave – although he imagines that she’d rather be wrapped in Parisian couture than her new shroud of native kudu skin. But he holds up a cautionary hand: No further dust-ups; we have quite enough on our plate. Rather, the young man fancies, 1789 was the year of the infant Mr P sopping on the issues of emancipation posed by the great Jeremy Bentham: The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?

Mary stamps her foot. Well, I certainly can and always could do all of those, so let’s not bother with questions so clearly directed at animals.

Mary may have appointed herself as chief agent, but with all the clamouring for a place in his story he, the poet, the subject of this narrative, will have to keep an eye on her. Keenly as he remembers the unfortunate natives of the Cape Colony, his story cannot accommodate all the abused of those unenlightened times. Now, to proceed. There may be confusion over who has chosen whom, but he is happy to submit to the eeny-meeny-miny-mo of being a subject. Being in the lady writer’s hands, he must wait for her to name him. An author with a good track record, a man of steady outputs, of sound reputation and at least a whiff of celebrity, would have been preferable, but beggars cannot choose. For all her dithering, they will have to make do, for at least she is familiar with the terrain. If only she were younger, more energetic, less hesitant – although it may be the mark of the times rather than of her age, race, sex. No choice then but to keep faith, to believe that she’ll manage. Besides, the indomitable Mary will be there to keep an eye on things.

He fears there’ll be some fanciful feminising, but is in no position to quibble. What will this female author make of him? Of the great cause of liberty? and of the question of slavery that centuries ago he had identified as a poisoned bowl which taints with leprosy the White Man’s soul and his civilizing mission? Above all, will she do justice to his poetry? He cannot expect passion to rise out of her prose, but he will settle for kindness, for tolerance of what has cruelly been dubbed the familiar trot of his iambic tetrameters. Justice and kindness are all he requires. And, of course, for the schoolchildren of the Cheviots to recognise his verse, recognise him as the champion of freedom. He notes that the lady writer’s brow furrows suspiciously, uncertainly. Perhaps justice and kindness cannot always be coaxed into partnership, so he may have to settle for kindness. Is it for her too an act of faith, as her hands hover over the new-fangled keyboard? Och, how she dithers, how she tries his patience; nevertheless, there is no hiding from her. She suspects him of dissembling, that kindness, justice, tolerance are not all that he requires, that he wants the attention of Edinburgh and London. Her frowning asks if it is not enough to be the Father of South African poetry. Well, no, and it is not so much to ask: he wants to be more than a colonial poet, wants to be known for God’s sake, in England and Scotland. (Our man has never cared about Wales and Ireland, Mary whispers.) He must try to think in contemporary terms, but why had Scotland cut him down? Persona non grata for defending natives at the Cape Colony and slaves in the West Indies, understandable perhaps in the bad old times when enrichment from the colonies was the order of the day, but it smarts to have been dismissed as a mere rhymster, a man with a bee in his bunnet and an axe to grind. No doubt he was too innovative, ahead of his time, combining as he did the roles of poet and activist when it was perhaps expected of him to choose between the two. Now, in another century, time has taken the sting from the bee, and the axe could surely be buried. Might a new generation of Scots living in comfort and security, and with their social consciences now keenly honed, not make allowances for both? Might weapons not be laid down with the birth of a new society and room made for the rehabilitation of a colonial struggle poet? Can his roots on the Scottish Borders not now be acknowledged? Has he not made history? He has in any case written many a poem celebrating that land itself, quite free of social comment, surely acceptable to these moderns?

He has in mind a genteel dinner table in Auld Reekie’s New Town, under ornately moulded ceilings, with starched napery and gleaming Caithness crystal – and not for auld lang syne. How splendid and dignified that would be, with dear Margaret by his side. Except, modest Margaret in sensible shoes would not want a resurrection of that kind, would frown upon the fanciness. He will have to hold his own in this new world. With the shadow of Mr Hyde scuttling through dark, dank passageways and Hogg’s demons prancing in silhouette on Arthur’s seat – midst all that doubling – could there not be a place for the neglected poet at such a twenty-first century literary table? Oh he’d even be prepared to put up with doing the honours at Burns Night, much as he deplored in the past the man’s folksy language, or his willingness to seek his fortune in Jamaica, willing, for heaven’s sake, to manage slaves on a sugar plantation. Perhaps it is best not to judge. That was after all a couple of years before the Revolution. And is it not often the task of the poet, as indeed it was in his own case, to travel to the very spring of abomination, if only to discover for himself the workings of injustice, and subsequently take on the fight for righteousness? Fortunately the man’s poetry and his abominable freemasons had saved the day, so that young Rabbie Burns, spared the journey to Jamaica and the ignominious life of a slaver, is highly revered at home. So why not he? This then is the grand project devised by Mary and the dear boy, his loyal protégés: the colonial poet brought home – on the wings of his verse against oppression.

Strictly speaking, on the wings of the woman writer’s prose. (She has perversely dismissed his polite term, lady writer.) If he frets about what she’ll do, how she will proceed, and from which angle, he is also resigned to the fact that it cannot be purely his story, not with all the others clamouring for being, clamouring for control. Whatever happens, some unknown beast will necessarily come yawning and blinking out of the attempt, but he is ready, is game for it, as they say. Invariably there will be a-slipping and a-sliding between third and first persons, elastic conjugations, role-switching perhaps between male and female, subject and author – this century it would seem is without limits – so all he can hope for is that the multi-faced monster will be of friendly mien, free at least of malice. He has had quite enough of neck-wrenching, of having turned first this cheek then that to the men of the master classes, be they political or literary. Practised in forbearance, and having survived so many constructions in the colony, both in life and in death – well, if this turns out to be yet another pooh-poohing, would that a final death follow. But thanks to the faithful protégés who have taken up the cudgels he is ready to give it a go, even in this baffling new world. The question, however, arises: what then is his role? The slipperiness of being a subject; for instance, will he as a white man be expected to step aside? What to do about this talk of a dead white man that he does not understand? He has prided himself on his dealings with all manner of men, but had never before come across the category of white man. He is somewhat tickled that a woman of her kind – ‘of colour’, as they say – has taken on the task (how the world has changed) and, of course, the idea of vengefulness cannot entirely be ruled out. Will he have to gird his loins for the new and unexpected ways in which to be dwarfed? Och, faith, he admonishes himself, the doubting Thomas must be cast out. Perhaps they could come to some kind of agreement, a contract of sorts.

These my subjects do not know of the actual contract, the one that Belinda alludes to with ever so delicate a smile. After that first book – which in retrospect seemed almost soothing to write compared with the terror that now besets me, the terror of expectations – I am quite simply paralysed. My agent, Belinda Montague, honey blonde, absurdly young, painfully, fashionably thin, beautifully shod, and one who slides unnervingly between being chirpy and matter-of-fact, sends by Royal Mail old-fashioned arty postcards, which is to say something from the Impressionists, knowing that I pretend not to read her emails. She avoids the word I, and always ends with: So-o-o looking forward to the typescript. Do send first chapters. Happy to read and advise.

Nowadays I barely check the picture, and after a cursory scan, toss the card into the recycle bin. For some months Belinda has been pretending that I do not mean what I say. Of course you won’t give up on the novel, she states. A carefree signature it was and now the contract holds, no matter what I decide. By way of encouraging me to do the right thing, she warns that I’d have to return the generous advance for the two-book deal. She does not mind my not replying. Predictably, the invitations to meet never include the legendary literary lunch. Does that institution no longer exist?

Belinda is committed to the genre of life-writing, a term she finds more appropriate than memoir. You have such rich experiences, just get them down on the page, she says. Aim for the artless. And try not to be arch; it’s not nice.

I, who have been incapable of beating out as much as a word, am not above taking advice. Belinda is right about my abominable tendency to be arch, and rather than fret about the word nice I should pay heed, for she may well turn out to be the one to save me from this motley group of phantoms.

Belinda may not have in mind my day as a supply teacher in a comprehensive school – how else am I supposed to live? – but my fingers fly across the keyboard as I imagine a recording of the morning’s experience, one that, as she recommends, is simply to be transferred to the screen. Easier to start with the end, when after a morning of colourful abuse from teenagers, I nipped into the head teacher’s office to announce that I’d had enough and was walking out in spite of my promise to stay until half-term. (See then, dear Belinda, how practised I am in breaking contracts. I’ll have to find a new way of keeping the wolf from the door.) The event meticulously recast into the third person, there are nevertheless a couple of persistent ‘I’s that still have to be replaced. In no time at all I also knock off a beginning to the piece, recount the day as accurately as possible. If I’ve achieved the desired artlessness, there is nothing to be done about its failure as a short story.

Belinda’s reply comes within two days, in tiny, spidery writing on a picture postcard of mud-coloured Gauguin girls: Absolutely bloody marvellous. Don’t even mention a wolf at the door – it’s a brilliant story, just waiting to be developed. Perhaps turn into first person and then a little toning down? We NEED novels of this kind. See, you were made for better things than teaching ignorant teenagers. Why not come up to London for lunch and we’ll go through your plan. Can’t wait. Xxx

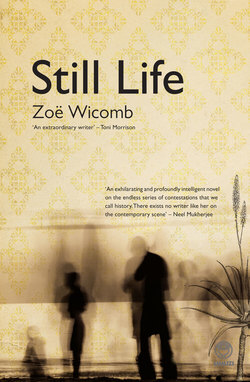

Her first X is always capitalised. So finally, the fabled literary lunch, the invitation to drop by, as if Scotland were a stone’s throw away and the journey indeed up to London. Mind you, no mention of the train fare. The word ‘plan’ makes me snigger. If only I had one, or even believed in the efficacy of having a plan. And if I were to have such a thing, it certainly would have nothing to do with uncouth kids in a classroom. I happen to believe in education and therefore cannot promote stories of failure. What can Belinda possibly mean by a novel when I’ve sent her what must pass for a short story? I have told her, admittedly over a year ago, explained in detail that the next novel was to be about the Father of South African poetry, Defender of a Free Press, Arch-enemy of the Cape Governor, Lord Charles Somerset, and as an Abolitionist, an enemy of all slavers: Thomas Pringle.

There, I’ve written his name – THOMAS PRINGLE – which surely has broken the spell.

But first a few more words about Belinda. Which may or may not be a delaying tactic: there is, as far as I can see, no reliable way of telling. Belinda is a feminist who believes in the category of women’s writing, which is to say women’s lives; believes in its value. She is not actually an editor. Belinda is an agent who believes her role to include that of editing, by which she means helping an author to shape a narrative. She demonstrates what she is after, what is required, by editing a page or ten – ever so lightly, she promises. She does not care for semicolons, and irony persistently ducks out of her ken. She has questioned me on unreliable characters and even insisted on the removal of what she calls an inconsistency.

Irony, I explain, but oh no, too obscure; readers would not get what you call irony, she insists. In other words, I am in her hands, although not in the way she imagines. But all things considered, including her slight frame, they are strong, supportive hands and I am indeed sorry to let her down in this way, especially since I’ve turned out to be her discovery. A puzzling term used by more than one reviewer, puzzling since I had, like anyone else, simply sent my first manuscript to Belinda, whom I had found in the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook. It was well after I signed up with her that she declared her belief that a novel should be a happy collaboration between writer, agent and editor. Vigilance therefore is the name of the game: there is no question of letting her loose on an unfinished manuscript.

A thumbnail sketch: Belinda is well dressed, usually in reliable linen, ever so lightly made up and often in fabulous red shoes; she speaks chummily (that’s when she slides down in her chair and waggles an exquisitely shod foot) about all women needing just a touch of eyeliner, a mere stain of lipstick. Then she crosses her lovely legs and puts her palms together thoughtfully. I know that she is preparing an assault when her fingertips are brought to rest ever so lightly on her top lip whilst staring fixedly ahead. (‘Ever so lightly’ is a favourite phrase of hers, her signature aesthetic; it is also a contagious term.) I fear that Belinda has too clear an idea of what women like myself ought to write. I fear that she believes readers to expect a true story, that she will have nothing other than could be read as Real Life; she has the capacity to turn my most fantastical tale into such a story, believes in the power, the necessity, of the authentic first person. Once, when we chatted about eating habits and dress sizes, she referred to my weight problems as a child. I have never been fat, I said, and she smiled knowingly, as if she had caught me out, as if I had forgotten a confession made in writing. Is that, I wonder, what drives me to the non-real, the magical? Even when my subjects are historical figures? And why do I now tease her with this nonsense about my day as a supply teacher? A shame about the lunch, but I do not want to see her in person. I shamelessly promise in writing to pursue the redemptive comprehensive-school novel, an updated, female version of To Sir, with Love, and Belinda, appeased, promises that we’ll have lunch next time, over the next chapter.

Perhaps I should give it a whirl; perhaps it will be less difficult to beat out a true story, although I will have to be on guard. Being a supply teacher for five weeks at St Mungo’s Hill Comprehensive School is not the whole story; hidden in it is another that has nothing to do with the ebullient racism of teenagers from the council estate fondly known as Muggers’ Hill, one that cannot be injected with redemptive elements. It is the story about Annie that may try to intrude; a story infused with shame that cannot be exorcised through writing, one that needs to be forgotten.

To Miss, with Love, I cackle wryly to myself – a matter of getting a move on. I really would hate to lose Belinda. Where would I find another agent? Who would put up with my dilly-dallying, shilly-shallying ways? Who would have a ditherer like me? I can after all not be discovered a second time. And there is the real possibility that Belinda will tire of jollying me along, will run out of encouraging words.

The slight poet, looking over my shoulder, feels his pectorals expand. Thomas Pringle. He has been named. Which, in this dismal state of affairs, must count as progress, he supposes. The stuff about Belinda and being a schoolmistress is an unhelpful digression and also a painful reminder of Harington House, although this lady writer’s Scottish Comprehensive School for the unruly lower orders is, of course, not to be compared with the 1820s Academy for Young Gentlemen that he established in Cape Town. But such nonsense will hopefully run its course. Now for a course of action, and for a while at least the others will have to step aside. Let him imagine for a moment that in this making he is she, she is he, that together they form a fleet set of hands that learn to fly in unison over the keyboard, pounding new life into the dormant material. It is a matter of pride: he refuses to remain a wraith, a spectral figure with hissing lungs. Unbelievable that he should have no choice but to wait in limbo for this woman to pull the strings at her will.

(I, on the other hand, reject the role of puppeteer; that is not it at all, I protest. I imagine him standing behind me, barely a silhouette, with hands resting on my shoulders, the masseur prodding and kneading with gentle reminders, with meaningful pressure on the taut muscles of my mutinous flesh. My fingers, despite the exercise of folding silver wrappers, are stiff and arthritic. As befits a ghost he is, after all, the one who commands, Remember me, and I, the shirker, will hesitate. See how he snatches at the least opportunity, his vanity irrepressible. See how he nurses a fond idea of coming into being at the Edinburgh Festival, bowing to applause, then stepping out of the Book Festival’s gloomy yurt into the gentle light of the modern, affluent Paris of the North.)

Would that the great John Fairbairn were restored to be his interlocutor, to tell of the heady days when together they brought civilisation to the beautiful, benighted Cape with the very first South African Journal and their fiery editorials in the Commercial Advertiser. Were it not for his untimely death, cruelly cut down after a mere forty-six years, he, Thomas, would have written his own Life and avoided this dependency on a woman. An account by Fairbairn would have been the next best thing. Fairbairn would have wrought the truth from the documents, the records and copious notes produced over the years for that very purpose, but och, his dear friend ever was a busy man who, with the many demands of the colony, could not always get round to things. And now, what a merry-go-round, having to start from scratch, and that with a strange woman whose reluctance is palpable. For a man of his stature it is hard to countenance that on this limen of the living he, Thomas Pringle, is being lined up for scrutiny.

Anyone with a South African education knows his story, or ought to know. But it may help to rehearse with objectivity the bare bones of that history and clarify his relationship with Mary and the young man, Hinza. Many a dictation has found its own momentum in the mind of the scribe, so this woman writer may well run with it, find her own voice, as they say.

He clears his throat, nods at her, and she dutifully scribbles as he dictates the sketch in the third person:

Born on the Borders, the poet Thomas Pringle was educated in Thurso and thereafter at Edinburgh University. In that city he led a distinguished literary life, befriended by the luminaries of the time. The extended Pringle family suffered difficulties, and assisted passages offered by the Colonial Office spurred him in 1820 to lead a party of Scots emigrants to the Cape Province. Once the family was settled as farmers in the Eastern Cape, Thomas and his wife Margaret went to Cape Town where with his bosom friend, John Fairbairn, he championed freedom of the press, started an academy for young gentlemen, and developed the National Library. Thomas keenly felt for the oppressed indigenous peoples. Their cause, he believed, would also be served through poetry that exposed their plight, but his progressive views fell foul of the autocratic governor, Lord Charles Somerset, whose persecution drove him out of the colony to London, where he alerted the world to the true nature of slavery at the Cape and exposed the conditions of the benighted native peoples of that land. The native boy, Hinza Marossi, whom he had rescued, was given permission to accompany the Pringles to London, but sadly he did not survive the inclement climate. As secretary for the Anti-Slavery Society, Thomas signed the Abolition Act in August 1833; he had earlier facilitated the writing of The History of Mary Prince, the first female slave narrative published in England, for which he was roundly reviled. He died in 1834 whilst preparing for his return to the Cape, but his reputation as the Father of South African Poetry endures.

This, in short, is the story that needs to be fleshed out. The time has come to challenge nineteenth-century class bias and pernicious Toryism, all of which were responsible for thwarting Pringle’s ambitions and keeping him out of the annals of history.

(I do, of course, know this much, but knowing also of the ambiguities, uncertainties, the alleged duplicities and repackaging of that life, I am not keen to meddle and offer judgement. No doubt there will be apologetics and smokescreens, let alone the residual beliefs of the times, for which I do not have the stomach. For the moment, however, I must listen without interruption to the voice, into which has crept an unmistakable whine.)

Cut down in my prime, Pringle complains, there was no time to convert our people to humanitarianism and the ways of Christian compassion for the natives. Certainly there was not enough time to hone my poetic skills. So short a life, so little achieved; nevertheless, there is enough to remember with pride: an admiring letter from none other than the great Coleridge himself, commending ‘the most perfect lyric poem in our language’; the support of Scott, Sir Walter no less, and also of James Hogg the Ettrick Shepherd whose death is lamented by the great Wordsworth; and my very own signature on the Act of the Emancipation of Slaves, a signature that my dearest Margaret held to her lips. But what did my countrymen across the border care? Not a fig. Rather, they would have me pilloried for my very commitment to freedom. I remember every vituperative word, the slanders are etched in my mind, and really I was powerless against the influential MacQueen of The Glasgow Courier, who called me a liar and advised that I be taken by the neck and with a good rattan or a Mauritius oxwhip be lashed through the streets of London. All for exposing the illegal slave trade in Mauritius. And such calumny published in Blackwood’s, the very journal established and once edited by me! Can anyone blame me for wanting to return to the world and recover my reputation in my beloved Scotland? In this new era, I would surely be guaranteed a hearing.

Yes, my time has come, he declaims, the time to gather stones together in the land that will embrace the poet and activist and allow me to belong to more than one country. Poetry has ever dissolved boundaries. If that makes me a vain man, so be it. In the words of Ecclesiastes, all is vanity, a striving after the wind, and nothing to be gained under the sun, yet I have seen with my own eyes all the oppressions practised under the sun, and have spoken out. If only there had been time left to roam the Eastern Cape and learn to sing in clearer voice of the koppies and vleis, the gold and violet sunsets, the stark thorn trees silhouetted in evening light, the honeyed mimosa. Pringle’s voice grows peevish: A longer life, and I would have managed to forge a suitable voice for the African veld. How churlish that I now should be reviled for resorting to English literary conventions, when there had simply not been time to attune the ear to the trill of the bokmakierie or the roar of lions! He beats his hollow chest – I am above all a poet – wheezes, and collapses into a coughing fit.

Mary stumbles, reaches over with nursing arms to pat his back and enfold him. No one, she consoles, pursing her full lips, no one under the sun escapes vanity; every one of us strives after the wind, and that, God’s own truth, is the end of it. So let’s get the project off the ground, get Mr P’s Life written, and as a matter of urgency fix up a contract with the writer. She, Mary, has after all in the past come a cropper in that respect. Uncivil perhaps to mention it now to one who has been her benefactor, who arranged for her history to be told, and she does of course not apportion blame, but a contract then might well have ensured that her own story be accurately written down.

Pringle withdraws from her embrace and clears his throat to continue. If only he’d been spared for a decade or two to see things through. A few years back at the Cape to keep an eye on the letter of the law, wipe out the persistence of slavery in its various guises, for sadly their fellow Europeans could not be trusted. With the Whigs in power, he and Fairbairn would have turned the colony into a beacon of truth and light with which to instil compassion and humanitarian values in the hearts of white men. Besides, as Fairbairn pointed out, to civilise and convert the natives into friendly customers would have been more profitable than to exterminate or reduce them to slavery.

Hinza, shaking his head, staggers to his feet, makes as if to speak, but Mary roughly pushes him back, gesturing vigorously, so that he sighs, slides down with his head in his hands and mutters, All astride the wind. None of which appears to be registered by the poet, who continues after yet another clearing of the throat.

Once Abolition was achieved, he would have returned to the Cape and settled for an appointment as resident magistrate in the new district on the Cafferland border, or even a modest post at the Kat River Mission, Dr Philip’s haven for Hottentots. In that heat and clear air his lungs would have healed, and allowed him to plan the next phase of moral and intellectual development for natives. But even the Whigs denied him, could not countenance him as Magistrate. Such are politicians: nothing is to be expected on the grounds of merit; his humble origins never to be forgotten, in spite of all his achievements. No, that office was kept for applicants of another caste, in spite of his high connections. And then, God’s inscrutable will – even with a ticket in his hand, the coffers packed, the sails of the Sherburne all but set as a fair wind swept east-north-east – to strike him down. Cruelly cut off when there was still so much to do.

And now this opportunity: a chance to resist fate and make known his life’s work. Let it not be forgotten that he had resisted injustice all his life. Had he not taken on the arrogance of the Cape governor, Lord Somerset and his Reign of Terror? Or the Scottish Tories? (slavers really, for those who benefit from slavery are no less than that). Besides, he has been made and remade so many times, in a hayrick of words heaped upon each other, the tattered old stories raked over, heaped in both glory and scorn, his precious verse laid out for scrutiny. The time has come to take control. There have been no concessions, none for a man on crutches, a man with poor lungs, and for that he feels gratitude of sorts. He has long since forgiven the malice of his own people, but it should be known that they were mistaken in overlooking him. He, Thomas Pringle, is yet a man of the Cheviots and the Eildon hills. Oh, for a ramble along Linton Loch in the rising light of February, the wind keen and the rain fresh, and there by the brae … there stands Nanny Potts, her hands on her hips, dear Pottsie waiting, scolding – the gypsies will come and take you away if you don’t eat your kale … the alphabet again, in best copperplate this time … do stop teasing your wee brother, or the gypsies … dear Nanny Potts … and the Paps of Eildon veiled in the rain …

Mary Prince is shaken by Mr P’s retreat into a childhood of which she knows nothing. She must focus, gather herself, remember the times in London when he stood firm for freedom. It is not easy to enter the wavering world of the past, but enter it she must. Mary rocks to and fro, hums a hallelujah, then mutters to herself in a low, throaty voice:

All night this house tosses on a dark sea, sways like a ship on fluid foundations. A black house, or one that turns black as night falls, as we lay ourselves down to rest. Women in the attic room and men in the parlour below, black as the kind night itself. We are bundled in bedrolls, arranged top to tail in rows. Not a slave ship at all, I say over and over. No, peaceful, benign, were it not for the past that presses its demons upon us in the dark, clamps its claws around our throats so that the women around me gargle their terror, scream, thrash wildly, strangling themselves in their bedclothes. How often I have to light a candle and soothe or scold them into silence. Heavens above, what namby-pamby sugar lumps these young women are; they would melt in the softest of English rain.

Cut out the feartie, as Mr P often says to me. Straighten those backbones, I scold. How on earth have you lot managed to escape from your masters? I am in charge. I give them no more than an hour to gather themselves. There is no sense in endless kindness, because mark you me, I say sternly, freedom is not for namby-pambies. Your bodies may have been abused and broken, may also be practised in recovery, but your minds have not been exercised in the ways that a new kind of living will demand of you. Now freed, do not imagine that you should rest on your oars, or go about banking on others. You will have to act of your own accord, make decisions, choices, and it takes strength to do so. No bed of roses, this kind of freedom, so cast the demons out once and for all. Have we not always found solace in the night when under kind black skies we sank, exhausted, into the oblivion of sleep? Besides, you know that here we are all protected. Safe in the house of Pringle.

The women weep; they moan about flames of hell. What I would not do for a decent night’s sleep! To hasten their recovery, to exorcise the demons – God will forgive me – I rush about the room with a lit candle in each hand and thrust the flickering flames up into dark corners. I mutter in a low, growling, voodoo voice the mumbo-jumbo that Mam chanted, even as she urged us to embrace blue-eyed God and the Christ-child Jesus. But I cannot keep it up; I see again, hear again Mammy’s deranged jabbering as she arrives on the boat to rake the salt at Turk’s Island, raving, and not as much as recognising me, her own honeychild. The candles have, thank God, been blown out in the rushing about, and I say, See, the light has gobbled up the demons. I press my hands over my ears and swallow the sound of Mam’s mad shrieks. No point in dwelling over the bitterness of that deeper past.

Spare a thought for others, I remonstrate. Our benefactors, wrenched out of the soft, plump arms of sleep by your bloodcurdling cries – they must be tossing and turning in their beds, wondering about the wisdom of taking in strange runaways. Really, I am tired of soothing; my days of being nursemaid are well and truly over. The younger girls still snuffle around for mothers; they look at me hungrily, would nuzzle into my breasts and clutch at my skirts if I were to give them an inch. There is no point in beating about the bush, no point in delaying their recovery, their independence. I am nobody’s bloody mother, I say as brutally as I can, slapping at my dugs; there is no milky bosom, no heart here to mother anyone. So pull yourselves together, brace yourselves for this new bittersweet life of freedom. Let us not blacken this house in vain.

We do not usually have so many stray people in the house, but there has been a fire at the Friends’ Meeting House in Islington. We have our suspicions about that fire, by no means the first. There are many respectable citizens who so believe in the rights of slave owners that they’d stoop to anything. The Pringles have taken in the female runaways, packed them into this small house like the hold of a slave ship.

We must all do what we can for these poor souls, Mrs P said, looking pointedly at me. You’ll have your attic to yourself again, Mary. The Society will place them with good abolitionist families as soon as they can, but for now you are responsible for these women. She does not think me unkind, but she knows how I value this precious little space with a bed of my own and the yellow patchwork cover I have stitched myself. Along the top edge, in the centre, I have sewn a large square, admittedly out of kilter with the rest. It is the whole of Daniel’s best grey handkerchief he gave me as keepsake, visible all day long, and at night I draw it up and bury my face in its story. Now with my cot pushed right up against the wall for space, I have folded away the cover, fearful that others may touch my heart so boldly laid out.

Often I trail my fingers along the perimeter of the walls, savouring the safety of a private space. Mrs P does not, of course, have a room to herself. She spends all night with a husband, and I wonder if she does not at times wish to explore the full measure of a bed, fling out her arms and settle where she will, hum a tune to herself, or light a candle and turn the pages of the good book as and when she pleases. That would be freedom indeed, to have had enough of the comfort of another body in bed. Not that I ever desired such freedom. Even Captain Abbott, a kind enough man, who came for a good number of years to my hut, would leave well before the night was over. Not until Daniel did I have the comfort and joy of a whole night with a husband, a free man, of waking up together in the light, even though there were some who said that a marriage could not be lawful without the blessing of the English Church. Which is, of course, a piece of nonsense, given that that church does not allow the marriage of slaves. Now I will never know whether after years of marriage I would desire the freedom of a bed of my own. I will never know if Daniel thinks I ought to have taken the risk of returning, but I know in my arthritic bones that if I were to return, the Woods’ punishment for speaking of their cruelty would be to sell me off to a far-flung place; that return to the island would never be a return to Daniel. Oh, the scales have wavered between freedom and love, but it is not that I have chosen freedom over love, or chosen, as my wicked enemies have accused, licentiousness over being with one husband. Love untested over the years will remain, steadfast, unwavering; rather, I chose between freedom and bondage, freely chose that over which I had control. Daniel would certainly have been snatched from me the very moment I laid my eyes on him. I shut my ears to the rumour, no doubt broadcast by the Woods, that he has found a new woman. With freedom secured here by Mr P, love is not a risk I could allow myself to take. Or should I have risked returning?

The women fall into fitful sleep after the demons have been driven out, but the demon in my heart beats against my ribcage, so that I slip out of the house into the icy night. With Mrs P’s handed-down coat draped hastily over my nightgown I hobble as fast as I can to the Heath. St Anthony’s fire flares in my gammy left leg, but the pounding of my heart is the only remedy for driving out thought. Had I miscalculated? Misread the wavering beam of the scales? Am I indeed a wicked selfish woman unworthy of the good Moravians who married us? I stumble as fast as I can across the Heath, circle it, over and over until my lungs burn and I can run no more. Falling down against a tree trunk, I wait for my breath to return and my burning leg to cool.

I do not know what to make of my years. The categories of young and old mean nothing to me, but here in London, in my heart, I feel for the first time the thrust of Spring’s spears, the delicate, lime scent of newborn leaf that sends the blood pumping in a heady rhythm. Mrs Pringle says that I am still young, that this is my second life granted by God. In which I grow in health and strength, especially since I avoid the white stuff to which slavers are addicted. Taking neither sugar nor the demon salt has calmed my rheumatism, so that distanced from greed and desire, my blood is freshened, fizzing with health. These tongue-tricking, white substances show nothing of their histories, the grubbiness with which they come to be in the world, hence I will have no truck with them. The herbalist in Highbury agrees that abstaining will soothe my rheumatic joints, and already I feel the pain subsiding. Mrs P says that freedom and, above all, belief flush the body out and cleanse the temple of God. I am grateful to Mrs P for not ever alluding to Daniel. Unlike others, she has not questioned my decision to remain in London. I will never forget her bashful eyes when she asked me to strip off my clothes, down to my naked flesh. The fire had been stoked and the curtains drawn. I am ashamed to say, she explained, that whilst I have no doubts at all, it is expected of me to confirm that I have seen on your body the evidence of ill-treatment and cruelty inflicted by your owners. Your history, so carefully written down by Miss Strickland, is thought to be a story of fantasy. She planted her feet firmly and ran her fingers over the welts and criss-crossed scars. I know my owners by each scar, I started, but she put a finger across her lips, hush now, then called briskly for Miss Strickland to witness the welted flesh.

The shame is of course not hers. No, shame belongs unquestioningly to Mr P’s enemies, who insist that he has maliciously published a sheaf of lies that is my story, that it is false and wrong to show slavery in such a vicious light.

Mary starts with a shudder. Hallelujah, she all but shouts. Bugger the Whigs and Tories, and to hell with their magistrates. Come now, Mr P, Nanny Potts is dead as a dormouse, and we’ve to get your history written. We’ll all go to your Eastern Cape, and our writer must come along to see for herself the state of affairs. Paint the region red, so we will.

Hush now Mary, Pringle remonstrates, but he flings out his arms all the same. Now that would be recompense, to go with you and Hinza on a trip to the Kat River. He had always had that in mind for the boy who would follow in his footsteps, follow a life of Christian humanitarianism in Africa. He reaches for Mary’s hand; he hopes that she’ll have some influence with the woman writer, for who knows what Missy has in mind for her marionette? And indeed the woman shakes her head, says that a trip will have to wait, that there is groundwork to be done right there.

How long he has waited for this moment of recovery, of his life’s work brought to attention, especially in his beloved Scotland. Vainglorious? No, that’s not it at all. Rather, it’s a matter of history which belongs to everyone, and in which he undoubtedly has had a humble role to play. Only, he could not have imagined his new maker to be like this, of this ilk. Och, the world has changed for sure and he must give her a chance, hope for the best. He must take this woman, who has after all agreed to tell the story, at face value. Is this not an opportunity to look afresh at those colliding worlds? Now, on this border where life and death jostle, he could stand the world on its head and cry, Hurrah, cry out loud that God is distant, but man is near! Phew! How thorny they turned out to be, those paths he trod, or rather, on his wooden crutches, flew along with the impatience of youth. Now, as he feels his hands fully shaped, feels the strength of his own fingers as they fall on her shoulders (attempting to guide her?), he believes that he could give it a whirl.

He can, of course, only hope, clutch at straws, but hope floods his being, infuses the blood that pulses in his veins. A whip crack – let’s get going! – sounds in the air. But first, there are boundaries to be set. Oh, he hopes that she will not start with that old tale about dear Nurse Potts dropping him as a three-year-old and then concealing his hip injury. The poor woman has suffered enough over that; and he certainly has never held a grudge against her; in the absence of a mother, she has come close to being one, has done her best. Besides, where has that story come from, and who knows if it is true? He may have once believed it, but the memory of a three-year-old cannot be relied on.

And pray God that she does not vulgarly pry into his marriage bed, that she spare Margaret who, like the tumbleweed that the dear woman loved to watch spinning across the barren plain, would at such intrusion somersault over and over in her grave. There has been distasteful lingering over Margaret’s lack of dowry, as if there were nothing else to say about her. Why on earth would anyone imagine that he, who had never been wealthy, would enrich himself through marriage? He could only be grateful that a woman with Margaret’s attributes had accepted him. Not that her piety did not irk, to begin with at least, but as for the ‘unfortunate marriage’, as theirs was branded, well, he could not have wished for better. A good, sensible woman, above reproach, whose unsuitability, it would seem, lay in the word ‘spinster’, as the grown men with their child-wives called her. For sure, Margaret was a good nine years older than he, but any sensible man would regard that as a blessing, and her motherly care could hardly be seen as a defect. He had much to learn from Margaret, and not only from her experience of farming that came in so handy on the foreign Cape frontier. Again he sees her dear face lifted at an angle, quizzically, lit with the beauty of reason, as she thoroughly considered his postulations, and gently led him to their flaws. Margaret, raised on a Scottish farm, devoid of airs and graces, how well and without a word of complaint she adapted to the African wilds. How appreciatively she listened to the nocturnal serenade of beasts; lulled to sleep by the roar of lions and the elephant’s trumpet, and daunted only by slithering snakes and spiders. And how eminently suitable without her dowry. He must insist on her being accurately drawn, but can that ever be the case? He fears not, thus he is prepared to fall to his knees, to beg for Margaret to be spared. No, that is not enough: he is prepared to fade back into oblivion, rather than have the dear, diffident woman’s life raked over. And so he arrives at the first clause of the contract.

Can this woman be trusted with the task, this story that is neither fish nor fowl, neither fact nor fiction? He fears that the writing machine that cuts and pastes might spawn all kinds of fanciful ideas, that the times will throw new light on things, that held up against new instruments of thought … oh, that is the risk that must be taken. For that he must gird his loins. But, all things considered, he is game for another take, a take of another kind. Call him needy, vain, and craving the attention of those who scorned him – a shabby confession it may be, though surely a justifiable sin – but he wants to be restored to his rightful place; a man of both the north and the south, a man traversing the hemispheres. Surely the desire to be known and acknowledged at home is not a vain striving after the wind.

Alas, his fickle friend Hogg and the great Sir Walter both gone – but Scotland remains the magical name that thrills to the heart like electric flame. Faith, that is what is required. Even if this lady, or rather woman writer has no understanding of frontier life, still, he will have faith. Dead white man he may be in her book, but now, dusted down, he feels himself growing stronger by the minute. If anything, his lust for living is fanned by her palpable scepticism.

Dare in commendam – he commends himself into her hands.

With his fingertips resting on my shoulders, I believe that we now have a contract of sorts. But what can that possibly mean, where the notions of truth and compassion that he demands are involved? Otherwise, he has given me carte blanche – no, I dissemble, for what choice does he have? There will inevitably be a struggle over past events and the long evening shadows that they cast over our story, his and mine. Again, I dissemble; my version will prevail, and there’s the rub.

Not only am I attracted to his inbetweenness, but there is more to unearth, there are the others spinning about his orbit, clamouring to be heard, to put in their ha’pennies’ worth. Except for the filmy figure that emerges and reveals herself as Margaret, the long-suffering wife, who has no desire to join the fray, who has been dragged in against her will, but who now, determined, on her way out, and without opening her eyes, remonstrates in a barely audible brogue, urging all to let be, to let bygones be bygones, to lay down all pens. As for Thomas’s reputation, she asks, what might that turn out to mean? A reckoning, a calculation? In this new light, the likelihood is that the books won’t balance. Pray desist, she whispers; it cannae be done. A chill breeze announces her departure.

A pity, since this tale could do with more sensible female voices. Thus I am further paralysed, no, stricken by this conflicting demand to desist. I must somehow buck up. I reach for more sweets, tear off the wrappers. My fingers try to smooth out the silver foil, but I fumble. Alas, I am unwell, unable, and must in sooth justify delay, must lie down and claim morbus sonticus.

Whilst the others keep their distance, there is no way of hiding from Mary, who eyes me and my bag of sweets with distaste. The old toff’s trick of big words, foreign words, ey? she sneers. As if I’ve not done my time in courts of law, the Court of the King’s Bench, no less. Her hands are on her hips. Look, this won’t do; this can’t be what all your learning boils down to, she carps. Is there not help to be found in a book? This is the time to act. See how Scotland is fast changing, with people now talking about the true horror of slavery, so what better time to introduce Mr P, reviled as he was then, as a new national hero? For God’s sake, pull yourself together, quit the brooding over where, when and how. Tell it as it is, she says, sounding like Belinda. Or consult a book, do something.

I may as well be sent to catch a falling star.

Mary’s impatience strikes a chord, brings home the obstacles. In Hinza’s words, we are all astride the wind. I am not up to it. Fear and cowardice, and distaste for pulling people up, for holding them to account. Who am I to judge? I cannot claim to be a woman true and fair.

Perhaps there is help to be found in a book.