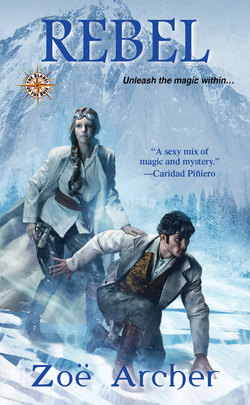

Читать книгу Rebel: - Zoe Archer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1 Encounters at the Trading Post

ОглавлениеThe Northwest Territory, 1875

The two men tumbled over the muddy ground, trading punches and kicks. A sloppy fight, made all the more clumsy by a surfeit of cheap whiskey and punctuated by grunts and curses. Nobody knew what the men were fighting about, least of all the men themselves. It didn’t matter. They just wanted to punch each other.

They rolled across the soggy earth, gathering a few interested onlookers. Bets of money, beaver pelts, and tobacco were placed. Odds were six to one that Three-Tooth Jim would make pemmican of Gravy Dan.

No one counted on the lawyer.

Jim and Dan, throwing elbows and snarling, careened right into the path of Nathan Lesperance, actually rolling across his boots as the attorney crossed the yard surrounding the trading post. Lesperance calmly reached down, picked up Three-Tooth Jim, and, with a composed, disinterested expression, slammed his own fist into the big trapper’s jaw. By the time Jim hit the ground, Lesperance had already performed the same service for Gravy Dan. In seconds, both trappers lay together in the mud, completely unconscious.

Lesperance sent a quick, flinty look toward the onlookers. The men—hardened mountain dwellers, miners, trappers, and Indians who had seen and survived the worst man and nature could dole out—all scurried away to other buildings surrounding the trading post.

Sergeant Williamson of the Northwest Mounted Police looked down at the insensate bodies of the trappers. “That wasn’t necessary, Mr. Lesperance,” he said with a shake of his head. Two young Mounties, Corporals Hastings and Mackenzie, hurried forward to drag the trappers away to the makeshift jail. “My men could have seen to the disturbance. Without resorting to fisticuffs.”

“My way’s faster,” said Lesperance.

“But you’re an attorney,” Williamson pointed out.

“I’m not your typical lawyer,” said Lesperance, dry.

On that, the sergeant had to agree. For one thing, most lawyers resembled prosperous bankers, their soft stomachs gently filling out their waistcoats, hands soft and manicured, a look of self-satisfaction in their fleshy, middle-aged faces. Nathan Lesperance looked hard as granite, hale, barely thirty, and more suited for a tough life in the wilderness than arguing the finer points of law in court or from behind a desk.

Williamson said, “I’ve never met a Native attorney before.”

Lesperance’s gaze was black as chipped obsidian, his words just as sharp. “I was taken from my tribe when I was a child and raised in a government school.”

“And you studied law there? And learned how to throw a mean left hook?”

“Yes, to both.”

“You must have a few stories to tell.”

A brief smile tilted the corner of Lesperance’s mouth, momentarily softening the precise planes of his face. “More than a few. I’ll tell you about the time I took on three miners making trouble in town—the only gold they found came out of their own fillings. But later, over a drink.” His smile faded. “I came here all the way from Victoria, so first let’s get this business taken care of.”

No Native had ever talked to Williamson this way. For one thing, Lesperance spoke flawless English, better, even, than most of the Mounties at the post. And there was no deference or hesitancy in Lesperance. In his words and eyes was a tacit challenge. Williamson had no desire to take up that challenge, lest he wind up lying in the mud, unconscious. And that seemed the least of what Lesperance seemed capable of. He wasn’t an especially big man, but no one could doubt his strength, judging by the way he filled out the shoulders of his heavy tweed jacket and by the facers he’d landed on both Jim and Dan.

“Of course, Mr. Lesperance,” the sergeant said quickly. He tugged on the red wool tunic of his uniform. “Please follow me. The Mounties keep a small garrison here. We have our own office, which serves as our mess, too, and a dormitory.” He gestured toward two of the low structures clustered around the main building of the trading post. Both the Mountie and the attorney began to walk. They passed fur trappers, clusters of Indian men and women, some white men in well-cut coats who could only be representatives for the Hudson’s Bay Company, here to buy furs, and horses and dogs. The Indians stared at Lesperance as he walked, no doubt just as amazed as Williamson to see a Native with his hair cut short, like a white man, and wearing entirely European-style clothing. Lesperance didn’t even walk as a Native might, with soft, careful steps. Instead, Williamson had to lengthen his stride to match Lesperance’s. “We do appreciate you traveling so far.”

“You could have just sent Douglas Prescott’s belongings to Victoria,” Lesperance said. “His next of kin agreed to it.”

“The Northwest Mounted Police take their responsibilities very seriously,” Williamson replied gravely. “We were created only last year to enforce law and order out here in the wilderness.”

“I thought it was to fight the whiskey trade.”

Williamson flushed at Lesperance’s blunt words. “That, too.” He cleared his throat. “I think you’ll find that Mrs. Bramfield also wants to conclude this Prescott business as soon as possible.”

“Bramfield. The woman who found Prescott.”

“The same.”

“And then her husband brought Prescott’s belongings to the fort.”

“Oh, no. Only she came to report Prescott’s death. She lives over a day’s ride from this trading post in a cabin by herself.”

This stopped Lesperance. He frowned at Williamson as the sergeant stumbled to a halt. “Alone?”

“Entirely alone.”

“Sounds dangerous.”

“It is,” agreed the sergeant. Lesperance resumed walking, so Williamson followed, saying, “But the locals say Astrid Bramfield has been on her own ever since she came to the Northwest Territory four years ago. She must know how to take care of herself. She even buried Prescott on her own, then brought his belongings to the Bow River Fort.”

“Maybe Mrs. Bramfield killed Prescott,” Lesperance suggested.

Williamson shook his head. “She’s a tough woman, but no killer. If murder was her aim, she didn’t need to bring Prescott’s possessions to the fort.”

“She may have kept some for herself.” Lesperance’s direct, forthright way of speaking reminded Williamson of his superiors at nearby Fort Macleod. He wasn’t certain whether the Mounted Police took Natives into their ranks, but Lesperance would have made an excellent Mountie—straightforward and determined.

“No, her honesty is impossible to deny, yet she refused to go back to the fort when it came time to meet you. This trading post was as far as she would come, and only then with quite a bit of reluctance.”

“A recluse.”

“Indeed. Even the Indians call her Hunter Shadow Woman. But you’ll find that these parts are full of peculiar characters. Here we are, our office-cum-mess. Right now it’s an office.”

They had reached one of the small log buildings that huddled near the trading post. It was barely more than a shack, a testament to the trading post’s rough surroundings. Out in the Northwest Territory, people made do with what they had. Over two thousand miles of prairie, mountains, and lakes stood between the Territory and the civilization of Toronto or Quebec. Sergeant Williamson stopped in the doorway and looked apologetic. “She’s inside. Please give me a moment to speak with her alone. Then we’ll have you and Mrs. Bramfield sign some papers and Prescott’s belongings will be released to you.”

Nathan gave a clipped nod and turned away when the sergeant went into the building. He heard voices within, the sergeant’s and a woman’s, and something, some rich quality in the timbre of her voice, sent immediate awareness tightening the surface of his skin. Something inside of him sharpened, like a knife being turned to the light. With a frown, he stepped farther away from the building and breathed in deep, looking around, assessing.

The trading post and the buildings that surrounded it were situated at the base of wooded foothills, and just beyond rose the jagged, snowcapped peaks of the Rocky Mountains. Even from a distance, such impassive, raw mountains awed, becoming godlike as they stretched toward the heavens. No shelter, only rock and sky. A cold wind blew down from the mountains, swirling in dusty clouds around the trading post yard. A man’s life would be a fragile thing out in those mountains, even more tenuous than within the isolated woods surrounding the post. Hard not to feel small and temporary when faced with beautiful, pitiless wilderness.

Home. Of a sort. His mother’s grandmother had come from these mountains, journeying all the way to Vancouver Island and taking a husband from one of the local fishing tribes. The few times Nathan had seen his mother, she would tell him stories of the mountains, legends of magical creatures and elemental spirits that lived within each spruce and aspen, but the teachers at his school always said such tales were at best only ridiculous and at worst idolatrous. He paid neither his mother nor the teachers any mind. He had his own path to follow.

He’d lived almost entirely in Fort Victoria, a bastion of Britishness on the west coast of a fledgling territory. Not once had he traveled the hundreds of arduous miles to see his great-grandmother’s ancestral home. He had never wanted to. The mountains were the past, and he moved forward. His business, his needs, kept him elsewhere. Until now.

No one at the firm where Nathan worked wanted to make the journey to some hardscrabble trading post out in the middle of rough country. Someone had to go. Douglas Prescott had been a valuable client, and remained so even after he abandoned his family to find adventure as a trapper. Poor sod had found more than adventure. He’d found death. And somebody from Steedman and Beall must go out and claim his belongings. A trip to the Northwest Territory meant weeks of grueling travel through unmapped terrain. And then turn around and do it all over again to get home.

In the silence that greeted Mr. Steedman’s announcement, Nathan had stepped forward to claim the task. Somebody muttered, “Of course, Lesperance. He’s just the contrary bastard to do it.”

So he’d gone, and thought of nothing in his long journey but returning and throwing down the packet of Prescott’s belongings on Steedman’s desk as everyone gaped. Yes, he was a savage, as they said he was behind his back, but it had taken a savage to get the job done. He liked nothing better than defying expectations.

But as he stared out at the pearl gray sky, stretching above the harsh, magnificent mountains and deep green forests, Nathan couldn’t shake the oddest sensation of being drawn toward the mountains and wilderness, invisible hands reaching out to him. Come to us, the woods seem to call. We are waiting.

“Mr. Lesperance?”

Nathan almost snarled in surprise as Sergeant Williamson appeared at his shoulder.

“Sorry,” the sergeant gulped. “I called your name several times, but you didn’t hear me. Mrs. Bramfield is waiting.”

Shaking his head at his imagination, Nathan followed Williamson into the low building. It took a moment for his eyes to adjust to the changing light. Small windows cut into the west-facing wall allowed watery sunlight to wash into the single room. A heavy, crude table and several chairs composed the room’s sole furnishings. Primitive as it was, there were homes in Victoria equally simple, especially belonging to the Indians and Chinese laborers. Once his vision cleared, Nathan barely noticed any of this. His attention was claimed entirely by the woman standing on the other side of the table.

From Sergeant Williamson’s description of Astrid Bramfield, Nathan had expected a much older woman, someone well on the other side of middle age, with the rough features and sturdy build of a female living alone in the wilderness. Beauty, youth, and femininity could not survive out here. He’d met fresh-faced girls going out to live pioneering lives with their husbands, only to return a few years later, haggard, weathered women with girlhood left long behind. Mrs. Bramfield would likely be much the same.

Yet Astrid Bramfield took his few preconceptions and obliterated them. She was much younger than he’d believed, closer to his own age of twenty-eight. She wore men’s clothing—a heavy coat, jacket, shirt, and slim trousers tucked into worn boots. The hilt of a stag-handled knife peered above the top of her boot. Despite the coat’s bulk, her figure revealed itself to be an elegant collection of curves, her waist narrow, the flare of her hips tapering down into long legs. A gun belt hugged her hips, a revolver holstered and ready for use. Her hair, the color of wheat in high summer, had been pulled back into a long braid, revealing a face of pristine, solemn loveliness. The golden freckles playfully dotting the bridge of her nose contrasted sharply with her gray eyes.

Those eyes. They burned him and would leave an afterimage branded into his mind. Never had Nathan seen such eyes, the hue of clouds just before a storm. It wasn’t their color so much as the depth of feeling he saw within them that seared him. Haunted, hunted. A feral creature, trapped within the body of a striking woman. That creature called to him, even more than the wilderness outside. A kinship there. Something dark inside of him stirred and awakened as he gazed into her eyes.

An animal within himself. He’d always felt it, fought it down every day. White men thought Indians were animals. He would prove them wrong, even if it meant brutally tethering a part of himself. But that hidden beast recognized her, saw its like within her. And demanded.

He felt his senses sharpen almost painfully, becoming aware of everything in the room—the fly buzzing in one corner, the sap smell of the wooden table. Most of all, her.

She stared at him with equal fascination, her hands spread upon the table as though leaning toward him without thought. Her breath came faster, her ripe pink lips slightly parted. He heard each intake and exhalation, saw the widening of her pupils within those storm eyes of hers.

A deep, barely audible growl rose in the back of Nathan’s throat as he started toward her.

The sound seemed to rouse them both from a trance. Nathan forced himself to take a step back, cursing himself. Hell. He wasn’t truly a damn animal.

Astrid Bramfield curled her hands into themselves and glanced away. The next time Nathan saw her eyes, they had become as remote and cold as a glacier.

“Mrs. Bramfield,” Sergeant Williamson said, entirely unaware of what had just transpired, “this is Nathan Lesperance. He is an attorney from the firm that represents Douglas Prescott.”

She gave Nathan a clipped nod but said nothing. He returned the nod, wary of her silence. Some white women found his presence to be an affront, the savage aping the dress and manners of a superior race; others thought him dangerously intriguing, like a pet wolf. How did Astrid Bramfield see him? And why did he care?

Despite her reserve, something charged and alive paced between them in the small room. They continued to regard each other across the table.

“Why don’t we sit?” the sergeant offered.

“I’ll stand,” Mrs. Bramfield said. Her voice was sensuous and low, unexpectedly cultured. She was English. That wasn’t entirely surprising. Canada was full of Britons, both English and Scottish. Why Astrid Bramfield’s Englishness, out of everything, should surprise Nathan, he had no idea, but the thought of a well-bred Englishwoman living the life of a solitary mountain man caught him off guard. He wondered what had driven her to seek isolation in this untamed corner of the world. At some point, there had to be a Mr. Bramfield.

The sergeant shifted uncomfortably on his feet. “Very well.” He gestured toward a small wooden box on the table. “Would you be so kind as to confirm that the items in that box are the same you found on Mr. Prescott’s body?”

Mrs. Bramfield opened the box and, as she did so, Nathan noticed her hands. At one time, they might have been a lady’s hands, slim and white. Now they were still slim, but they looked far more capable and used to hard work than any other lady’s hands. His vision, still sharper than he could ever remember, noted the calluses that thickened the skin of her fingers and lined her palms. For some reason, he found the sight arousing. A plain wedding band gleamed on her left hand.

One by one, she took items out of the box and laid them onto the table. A pocket watch. A battered book. Packets of letters. Nothing of real value. Nathan ground his teeth together. For this he had traveled hundreds of miles? Damn overzealous Mounties, taking their new responsibilities as peacekeepers too seriously. But then he watched Astrid Bramfield as she removed the dead man’s belongings from their container, and couldn’t feel that this journey had been entirely worthless.

“Yes,” she said after examining everything in the box. “These are the same items. Nothing is missing.”

“Very good.” The sergeant handed her several pieces of paper, as well as a pen and bottle of ink. “If you’ll just sign these affidavits, we can release the items into Mr. Lesperance’s custody.”

Wordlessly, she bent over the papers and signed them. The only sound in the small building was the pen’s nib scratching over the paper. As she wrote, Nathan saw that, in the pale sunlight, a few glints of silver threaded through her golden hair. But her skin was unlined and smooth. Something had marked her, changed her, and he wanted to know what.

“Please countersign the documents, Mr. Lesperance,” Williamson said when Mrs. Bramfield was done.

Nathan reached for the pen to take it from her. Doing so, his fingers grazed hers. A brush fire spread from his fingertips through his whole body at the brief contact. She drew in a shaking, startled breath. The pen fell to the table, scattering droplets of ink like dark blood across the papers.

Sergeant Williamson darted forward, quickly blotting the ink with a handkerchief. “Not to worry, not to worry,” he said with a nervous laugh. “If you like, I can have Corporal Mackenzie, our clerk, draw up some new affidavits.”

“No need,” Nathan said. At the sound of his voice, Astrid Bramfield pressed her lips together until they formed a tight line. She suddenly paced over to where a Hudson Bay blanket was tacked to the wall as a gesture toward décor, and became deeply engrossed in studying the woven pattern.

Nathan could practically see her vibrating with tension. She wore it all around her like armor. He knew she didn’t want to be at the trading post, but there seemed to be more to her sense of unease. He was unsettling her. Well, now they were even.

Intrigued, Nathan signed the documents, noting that Mrs. Bramfield’s handwriting was both feminine and bold. Astrid Anderson Bramfield. He found himself touching her name, little caring that the ink smudged on the paper and stained his fingertips. Nathan had the urge to inhale deeply over the affidavits, as if he could draw her scent up from the paper. He shook himself. What the hell had gotten into him? He must be tired. He’d been riding hard for weeks, and it had been nearly two months since he’d been with a woman. That was the only explanation that made any sense.

Once the papers were all signed, Sergeant Williamson examined them. “Everything looks to be in order. The Northwest Mounted Police will be happy to release Mr. Prescott’s belongings into your care, Mr. Lesperance.”

“Am I finished here?” Mrs. Bramfield said before Nathan could answer the sergeant.

Williamson blinked. “I believe so.”

“Good.” She picked up a broad-brimmed, low-crowned hat and set it on her head. Without another word, she strode from the building, but not before stepping around Nathan as one might edge past a chained beast. Then she was gone.

For a moment, Nathan and Williamson stared at each other. A second later, Nathan was out the door and in pursuit.

He caught up with her near the corral. She was already shouldering a pack and a rifle with practiced ease, taking the muddy ground in long, quick strides. Nathan didn’t miss the way most of the men’s eyes followed her. Women were rare sights out in the wild, and trouser-clad, handsome women even more rare. Yet he had the feeling that even if the trading post yard was full of pretty women in pants, Astrid Bramfield would stand out like a star at dawn.

“Douglas Prescott’s family appreciates you giving him a decent burial,” Nathan said, easily keeping pace. “They want to give you a reward.”

She shot him a hard look but didn’t slow. “I don’t want anything.”

“I’m sure you don’t,” he murmured.

They reached the corral, and she walked briskly toward a bay mare. She threw the Indian boy watching her horse a coin. The boy said something to her in his language, glancing at Nathan, and she answered sharply. The boy scampered off.

“What did he say?” Nathan asked.

“He wanted to know what tribe you come from,” she said. “I said I didn’t know.” Without asking for any assistance, she hooked her boot into the stirrup and mounted her horse in a single, fluid movement. She tugged on some heavy rawhide gloves before taking up the reins.

“Cowichan,” he said. “Government people took me when I was small. Raised me in a school. I never knew the people of my tribe.”

Something in his tone had her looking down at him. Their eyes caught and held, and he felt it again, drawing tight between them, a heat and awareness that had a profound resonance. “I’m sorry,” she said. Her simple words held more real sympathy than anything anyone else had ever said to him.

“You could have kept Prescott’s things for yourself,” he said, gazing up at her. “People die out here all the time, and no one ever knows.”

“Those who love him would know,” she said, her words like soft fire on his flesh. “And it was for them I took Prescott’s belongings to the Mounties. They would want something of his to help them remember.”

She spoke plainly, almost without affect, but he heard it just the same, the raw hurt that throbbed just beneath the surface. She’d shown him a small piece of her heart, and he recognized it as a gift.

Looking into her eyes, into the stern beauty of her face, he dove through the surfaces of words and gestures to the woman beneath. Wounded within, a fierce need to protect herself. And beneath even that, a heart that burned white-hot, blazing its way through the world.

He understood just then that Astrid Bramfield spoke to him like a man, not a barely tamed savage or object of curiosity. The only woman to have ever truly done so. Even the Native women he knew could never place him, since he was neither entirely absorbed into the white world nor fully Indian. But this guarded woman saw him as he was, without judgment.

He placed a hand on the reins of her horse. “Don’t leave.” He truly didn’t want her to go. Nathan had a feeling that once Astrid Bramfield left this dingy little trading post, she would disappear into the wilderness and he would never see her again. The thought pained him, even though he’d met her just minutes before.

“I can’t stay.”

“Have a meal with me,” he pressed. He struggled not to seize her, pull her down from the saddle, and drag her to some shadowed corner. He clenched his jaw, fighting the urge. He was civilized, damn it, not the savage everyone thought him to be. But the compulsion was strong, growing stronger the more he thought about her leaving. He switched tactics. “It’s already growing dark. Could be dangerous.”

She said with no pride, “The dark doesn’t frighten me.”

“Not much does.”

Her jaw tightened and a flash of something—pain, regret—sparked in her eyes before she tugged the reins from his grasp. She wheeled her horse around, forcing him to step back.

“Good-bye, Mr. Lesperance,” she said. Then she set her heels to her horse, and the animal surged forward, out of the corral. It cantered across the rough trail leading away from the trading post, taking her with it. Nathan battled the urge to grab a horse and follow. Instead, he turned and walked toward where Sergeant Williamson stood holding the box of Prescott’s things, deliberately not glancing back to try to get a final glimpse of Astrid Bramfield before she vanished. His inner beast snarled at him.

His senses were still unusually keen. Scents, sights, and sounds inundated him until he felt almost dizzy from them. The minerals in the mud. The horses’ snorting and pawing, rattling their tack. A man’s laugh, harsh and quick. And, more than ever, the persistent pull winding down from the mountains like a green surge, drawing him toward their rocky heights and shadowed gullies.

“What do you know about her?” Nathan demanded of the sergeant without preamble.

Williamson seemed more accustomed to the way Nathan spoke. He hardly blinked as he said, “Very little. She comes to the post a few times a year. Never stays overnight.”

“Tell me about her husband.”

“All anyone knows is that she’s a widow.” The sergeant shrugged. “Honestly, Mr. Lesperance, she spoke as much to you in the past fifteen minutes as she has to anyone in four years. Interested in paying court?” Williamson sounded both amused and appalled by the idea that a Native, even one as civilized as Nathan, would consider wooing a white woman. White men took Native wives, especially out in the wilderness, though few genuinely married them in the eyes of God and the law. It almost never happened the other way around, with an Indian man taking a white wife. If he’d been inclined toward marriage, which he wasn’t, Nathan’s choices would have been slim. Still, he didn’t like to be reminded of yet another way he lived on the fringes of society. The idea that a woman like Astrid Bramfield could never be his particularly stuck in his craw.

“I’m leaving tomorrow,” Nathan growled.

“Your guide won’t be willing to leave again so soon,” Williamson said in surprise.

“I’ll find another.” Everything about this place set Nathan on edge, unbalanced him. Victoria wasn’t anything more than a decent-sized town, its ranks swelling periodically when gold was discovered nearby, so it wasn’t wilderness itself that troubled Nathan. What unsettled him, roused the animal within, was this wilderness. And Astrid Bramfield.

“There’s no shortage of men who’d oblige,” the sergeant said, “if the price is good.”

Nathan had money in abundance, not only provided by the firm, but his own pocket. “They’ll be satisfied with my terms.”

“You can find good trail guides at the saloon.” Williamson grimaced. “It isn’t so much a saloon as it is a cramped room where they serve whiskey. Legal whiskey, of course,” he added quickly.

“Of course,” Nathan replied, dry. “Keep hold of Prescott’s belongings for a little while longer. I don’t want some drunk trapper getting curious.”

“You can handle yourself in a fight,” Williamson said.

“Getting another man’s blood on my clothes is a damned nuisance.”

After Williamson nodded, Nathan set off for the so-called saloon. He wanted to secure his return journey as soon as possible. He needed to get back to the cold, moist air of Vancouver Island. This mountain atmosphere played havoc with his senses, luring the beast inside of him with siren songs of wild freedom. He didn’t care what that damned animal wanted—he would leave here and leave her.

An hour later, Nathan had drunk some of the most throat-shredding whiskey he’d ever tasted and found himself a guide who went by the name Uncle Ned. Nathan doubted anybody would willingly claim Ned as a relative, given the guide’s preference for wolverine pelts as outerwear, complete with heads, but Ned’s skill as a guide weren’t in doubt. Even Williamson said that Nathan had made a good choice in Uncle Ned.

When Nathan emerged from the saloon, dusk had crept further over the trading post and its outbuildings. The men had grown more raucous with the approach of darkness. And there was considerable commotion surrounding a group of riders who had entered the yard around the post while Nathan had been securing a guide. One of the men had a hooded peregrine falcon perched on his glove. Not only were the riders all equipped with prime horseflesh, but also their gear was top of the line. Saddles, guns, packs. All of it excellent quality. As Nathan walked past the riders, he noted their equipment was English, likely purchased from one of London’s most esteemed outfitters. He’d seen a few examples pass through Victoria and could recognize the manufacturers.

“You,” snapped one of the men to Nathan. Like Astrid Bramfield, this man had a genteel English accent, but none of her melodiousness. He glanced around the trading post with undisguised disgust. “You guide us? Big money. Buy lots of firewater.” The man, tall and fair, jingled a pouch of coins at his waist.

“I’m not from these parts,” Nathan answered, his voice flat. “But I’d be happy to lead you straight to hell.”

The man gaped at Nathan. As he stood there in astonishment, his companion with the falcon approached.

“This Indian giving you trouble, Staunton?”

Before either Nathan or the man called Staunton spoke, the falcon let out a sudden, piercing shriek. Nathan’s sensitive hearing turned the sound to an excruciating screech, and he fought the urge to wince. Both Englishmen stared at the bird, amazed, as it continued to cry and flap its wings, struggling against its jesses as if it meant to swoop at Nathan. The men traded looks with each other, and their other two companions also took keen notice.

As did the rest of the inhabitants of the trading post. The falcon persisted in its noise, drawing the attention of everyone, including Mounties and Natives, who gawked as though Nathan and the bird were part of the same traveling carnival.

Nathan wanted to grab the bird and tear it apart. Instead, he made himself stride away. He didn’t know what had disturbed the falcon, but he wasn’t much interested in finding out. If he stayed near the Englishmen any longer, he’d wind up punching them as he had the two drunk trappers earlier, only with less delicacy. He heard the Englishmen murmuring to each other as the bird’s cries died down. With his hearing so sharp, he could have learned what the men were saying, but he didn’t care. They reminded him of some of the elite families on Victoria, touring the schools for Natives and praising the little red children for being so eager to adopt white ways. But when the red children grew up and presumed to take a place in society beside them, then they were less full of praise and more condemning. Let the Natives become carpenters or cannery workers. Respected, affluent citizens? Government officials or attorneys? No.

Nathan had spent his life challenging people like that, but his vehicle was the law. From the inside out, he’d smash apart the edifices of their prejudice, and the victory would be all the sweeter because they’d put the hammer into his hands.

Not now. All he cared about now was rinsing off some of the day’s grime, getting a hot meal, and having a decent night’s sleep. It had been a long day, an even longer journey, and tomorrow it would begin all over again. He’d forget about Astrid Bramfield. She seemed eager to forget him.

As Nathan headed toward the Mounties’ dormitory, a flash in the corner of his eye caught his attention. He turned, thinking he saw a woman, a redheaded woman, skulking close to the wooden wall enclosing the trading post. He saw nothing, and debated whether to investigate. Normally he would have dismissed such a suspicion. After all, anything could exist in the margins of one’s vision, even monsters and magic. But ever since he’d met Astrid Bramfield, there was no denying his senses were sharper. He started in the direction where he thought he’d seen the red-haired woman.

“Mr. Lesperance,” called Corporal Mackenzie, waving to him, “please, come and have supper with us.”

Nathan cast a look over his shoulder, where the woman had possibly been, but then cleared his head of fancies. It didn’t matter if there were passels of redheads haunting the trading post. He was leaving there soon, as soon as possible.

Mounties worked well with Natives. Without Native guides, they all would have been dead on the slow, far march from Winnipeg to the Northwest Territory. Tribes respected the Mounties for curbing the devastating border whiskey trade. So Nathan was welcomed at the Mounties’ table that night, the company consisting of him, Sergeant Williamson, and Corporals Mackenzie and Hastings. They ate a spread of roast elk, potatoes, and biscuits while telling stories of their adventures bringing order to the wild.

“Sounds damned wonderful,” Nathan admitted over his beer. “Getting results through brains and action.” More satisfying, in the short run, than what he tried to accomplish in Victoria.

“It is,” agreed Corporal Mackenzie. “It’s what we all signed on for. Being out in the field, tracking criminals, keeping the peace.” He grinned.

“Everyone saw how you put down Three-Tooth Jim and Gravy Dan,” said Corporal Hastings, a man hardly old enough to shave. “Maybe you should consider joining up. You’d be grand as a Mountie.”

Williamson and Nathan shared a look. The boy was too young and naive to realize that what he spoke of would likely never be accepted by headquarters at Fort Dufferin.

“Thanks, all the same,” Nathan said. “But I’ve got a life waiting for me in Victoria.” A life that seemed, at that moment, too tame. He already chafed against the restraints of society there, and no one, not a soul, knew about Nathan’s late-night restlessness, his compulsion to run. He was always careful.

“Just think about it,” pressed the young corporal. He yelped. “You kicked me, Mackenzie!”

Corporal Mackenzie rolled his eyes, and Sergeant Williamson hurriedly changed the subject. “What do you know about those Englishmen who arrived today, Hastings? The ones with the falcon.”

“The falcon that took an instant dislike to Mr. Lesperance,” Corporal Mackenzie added with a wry smile. Nathan scowled down at his battered enameled tin plate.

Hastings, eager to shine in the eyes of his superior, pulled out a notepad from his pocket. “A scientific expedition, all the way from London,” he read.

“Scientific,” repeated Williamson. “Botany? Zoology?”

Hastings flushed. “He wasn’t specific, sir. I tried to get more details but he gave me a lot of bluster, saying he was a very important man in England and he didn’t have time to waste on”—he cleared his throat and turned redder, matching his jacket—“‘boys in pretend uniforms.’”

All the Mounties grumbled at this.

“But they did hire three mountain men as guides,” Hastings added. “And I heard they’re heading west at first light.”

“Good work, Corporal,” Williamson said, and Hastings beamed. He turned to Nathan. “Are you sure you want to leave tomorrow, Lesperance? It’s jolly exciting around here. Always something going on.”

“I’m sure,” said Nathan, thinking once more of Astrid Bramfield’s silver eyes. A welcome distraction came when something brushed against his leg. He glanced down to see an enormous orange tabby cat twining between his boots. The cat placed its paws on his knee and chirped. Nathan stroked the cat’s head and was rewarded with a series of purrs.

“That’s Calgary,” said Mackenzie. “I named him after the place in Scotland where my pa is from. He isn’t usually this friendly. Just eats and sleeps all day. Terrible mouser.”

“You’ve got a way with animals,” Williamson noted as Calgary tried to climb into Nathan’s lap.

“Except those Brits’ falcon,” Nathan said.

The men continued to share stories until darkness fell completely, and the only light came from their pipes and the lantern on their table. At last, aching with fatigue, Nathan stood, dumping the irate Calgary from his lap, and bid the Mounties good night. Tomorrow would be another long day.

Once outside, Nathan took a deep breath of night air. Most everyone at the trading post was either asleep, passed out, or had since left, so the evening was cold and silent. Hardly any light penetrated the darkness, save for the glinting stars and waning moon. Yet Nathan felt them, just the same, the huge, dark forms of the mountains, pulling on him like a lodestone. He’d struggled against it all evening, and now that he was out of doors, their draw became sharp, insistent. He gritted his teeth against it. Come to us. We await you.

So strong was their pull, Nathan didn’t notice the shadowed forms creeping up behind him. By the time he became aware of them, it was too late. He felt several men leap upon him, binding him, forcing a gag into his mouth. He struggled fiercely, almost dislodging them, but there were too many. A falcon cried. Something exploded behind his eyes and then he was swallowed by nothingness.