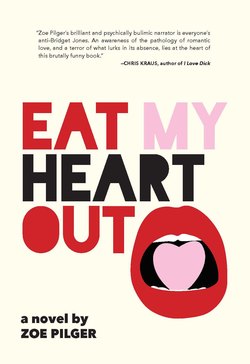

Читать книгу Eat My Heart Out - Zoe Pilger - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHREE

Dear Vic,

Last night was truly extraordinary. Thank you.

Plato said that we were all born with two heads and four arms and four legs. I didn’t have a Hellenistic education because I went to a comprehensive school. I’m the only one of all my friends who went to a comprehensive school—apart from Sebastian, who isn’t my friend or my boyfriend anymore. He comes from a decadent, progressive family in Islington. He is one of six siblings who all look intersex, but they are all excellent at a musical instrument. I never did that either. Nietzsche would say I suffer from ressentiment.

Sebastian looks a bit like a Nietzschean blond beast. He started off at an exclusive left-wing boarding school, but then he got expelled at the age of twelve for fighting. He had to fight at my school too. The rude boys hated him because he was upper-middle class. I remember this one time when we were thirteen. We were in the hall between lessons. It was packed with people screaming and fighting and the teachers couldn’t control it. Sebastian pretended that he was pushed too close to me and held my hand by accident but I knew he did it on purpose. So I bent his hand backward. He was in a lot of pain but he wouldn’t scream for mercy. Instead he grabbed my hair and got me in a headlock. I bit his stomach. He wouldn’t let go and I wouldn’t let go. Neither one of us would ever let go.

We walked to the next lesson like that—a two-headed monster. It took the teacher at least half an hour to separate us. There was a circle of red marks on his white shirt—it was his blood, but it was my teeth.

Soon after that we fell in love.

Plato said that Zeus got angry and ripped all the hermaphrodites in half and made them into normal humans with only one head, two arms, and two legs. But they were doomed by an overwhelming sense of what they had lost. They were doomed to spend the rest of their lives searching for the half that they lost.

That’s how I’ve felt since I left your terraced house this morning. I spoke to the operators in the kitchen. They seemed really nice. What’s the name of their blog again?

With love,

Ann-Marie X

Back at the apartment, I lay on my bed for about three hours, watching Beyoncé’s “Deja Vu” video again and again and again. I watched her shimmy across the screen in a colonial-style grass skirt against a fake backdrop of dry earth and deep sky. She waved her beautiful arms around dementedly and kicked up the dust and then collapsed on the floor at the song’s crescendo, screaming about seeing her lover everywhere she went.

I pulled on my red silk kimono. The bathroom door was closed. I could hear Freddie running a bath and the squeal of an American cartoon.

“I’m coming to jump in there with you in just about ten minutes!” I shouted.

I had a look in the living room; it was fucked. Freddie’s portrait of me had been taken down from the wall and lay on the coffee table, covered in white dust and a rolled note. He painted it last summer on the roof at Hammerton Hall, the stately home where his father keeps all his art but never visits. Maxine, the housekeeper, had decked the roof out in fairy lights and candles because I think she wanted to turn Freddie straight. I had lain on blue velvet with my clothes off while he pretended to be seized by inspiration: a cigarette clenched between his teeth, splattered with paint the approximate shade of my skin. He had insisted that I wear a sapphire necklace that belonged to his mother. The result was a hybrid of Francis Bacon and soft-focus 70s porn. My mouth was a yawning black chasm and there were boxing gloves on my feet, but my lips and nipples were painted a tender pink. Maxine said that the portrait made me look about ten times more beautiful than I am in real life. Freddie loathed it; he couldn’t even accept it as self-consciously derivative. He said that it revealed him in a light that he didn’t want to be revealed in. I said that I thought the portrait was supposed to be of me? He said no—he had exposed himself as sentimental, as sentimental as a dirty old flasher in the park. I asked him: “How is a flasher sentimental?” And he said: “A flasher is just a romantic at heart. He just wants to be naked under the trees.” Freddie decided to give up painting altogether and invest his creative potency in video art. Now he only works in 8 mm.

Next to the chaise longue, there was a bust of Freddie’s uncle, Professor Timothy Frank, an esteemed anthropologist. The bust was commissioned by Freddie’s father who hated Freddie’s uncle. It looked like a remnant of an exploded car factory. The face was more or less a steering wheel embedded in a tire.

There was a lot of tribal hunting equipment too: scythes and axes, charged with a preternatural energy. They were full of wrath. They didn’t want to be estranged from their country of origin. There was a taxidermied peacock with fanned feathers.

In the kitchen, I ate some chicken livers and stale bread, checking my phone constantly. Vic hadn’t called or texted.

I went back upstairs.

Now the bathroom door was ajar. Disney’s The Little Mermaid was playing on our old mini TV, which stood on a marble plinth at the end of the bath. I watched the screen as I got my tights off in the hall.

“Keep singing!” barked Ursula the sea witch, reaching her phantom fingers down Ariel’s throat and usurping her voice.

Ariel spasmed; her tail turned into legs.

“This bit is, like, so romantic,” came a voice. It wasn’t Freddie’s voice.

I pushed the door open.

There was a boy in the bath. He wasn’t Freddie.

“Who the fuck are you?” I said.

The boy turned his freckled, crying face toward me.

I knew who he was; he was Samuel, Allegra’s younger brother. I hadn’t seen him since the day after the night of the crème de menthe—that was nearly two years ago. He used to be a preppy little bastard, but now he had transformed into a hipster of some description.

“Get out,” I said.

His hair was ginger, not black like hers. His body was thin and white, but not exactly alabaster like hers. His eyes were not gray like hers, but hazel. He had the same high domed forehead as her and I hated him violently.

I attempted to haul the TV into the bathwater.

He leaped out.

The cord strained. The TV rocked on the edge.

It didn’t go in.

Now Ariel was scrabbling on the shore, trying to figure out how to walk.

Samuel clung to me, wet and ludicrous. I pushed him off. He was almost as tall as Vic. With shaking hands, he returned the TV to its plinth. He got back in the water.

A moronic smile appeared on his face. “Look.” He pointed to the screen.

Eric the prince was trying to interpret Ariel’s damp-eyed sign language. They were standing by a rock on the beach.

Samuel put on my exfoliating mitts and lathered himself up. “Freddie is so analog,” he said. “That’s why I love him.”

I tried to drag Samuel out of the bath by the arm, but he shook me off with ease. He said, sadly: “Yeah, Freddie told me you had a lot of anger management issues after you totally caught the G. She gave you the G. Because even though people are from the same blood buffet, it doesn’t mean they’re the same type of sick gangster. What she did was Frigidaire.”

“What the fuck are you talking about?” I said. “Where’s Freddie?”

He guffawed. “Sleeping it off. Last night we got more than shellacked and Freddie boggled and, like, got hit on by a flavorless but then he hit on me and I was like, you can totally tap this. You’re a juicer and a hypo but I love you.”

“What?”

“Oh, yeah, right.” He blushed. “That’s how they speak in Brooklyn. In Williamsburg. I’m reading this.” A wet copy of Shoplifting from American Apparel by Tao Lin lay on the bath mat. “Have you read it? Freddie told me to read it. He’s going to improve me.”

“That’s mine,” I said. “I haven’t read it.”

He laughed. “Where are my manners, babes?” He held out his hand. “I’m Samuel.”

“I remember.” I didn’t take his hand.

“Freddie told me that you two are, like, majorly liquid even though he’s not a CK1.”

“A what?”

“That you’re on a spectrum.”

“We’re not on a spectrum.”

“He said it was like The Cement Garden and incestuous and shit all up in this place but that I shouldn’t be perturbed if you got jealous because one thing he likes and can’t stand about you is your temper.” Samuel turned back to the TV.

Now the crazy French chef was trying to murder the blatantly racist rendition of a crab with a cleaver.

Samuel laughed until tears welled up in his eyes again. He addressed me with sincerity: “You’re the coolest bitch I’ve ever seen.”

Freddie was concealed inside the silk drapes of his four-poster. The room was fetid and smelled of yeast. Sex. The curtains were closed, but I could see the full blue condom that had belly flopped into a brogue.

I crawled into the bed. “Freddie.”

He was asleep.

“Freddie, why did you let Allegra’s brother in here?” I pried his eyelids open. His eyeballs were a brilliant red. “Get him out.”

Freddie smiled and pulled me down against him so that my face was pressed against his naked chest. “This is nice,” he said. “I love you.” He kissed me on the forehead.

I lay down next to him and smoked a cigarette. Then I got up and attempted to lock the door, but the lock was broken.

Samuel appeared wrapped in my towel and sang in a falsetto: “Say My Name.” He got into bed too.

I was stuck between them.

The gloom was unbearable; I got up and opened the curtains.

“Freddie says you love Beyoncé because you went to a black school and that is sick,” said Samuel.

The morning light seemed to wash the room. I saw the full horror: more full condoms; three more. More white dust.

Now Freddie and Samuel were kissing, graphically.

I shook Freddie until he turned away from Samuel and turned toward me. “It’s finally happened!” I said. “I felt it—the coup de foudre! Vic and I had sex so hard last night that now I can’t even walk properly!”

“Deck,” said Samuel.

I spat in his face.

He looked like he would cry again.

“That’s not very nice, is it?” said Freddie. “You got on very well with Samuel when we all spent that lovely weekend together in Buckinghamshire.” He turned to Samuel: “When your parents were in the Maldives.”

“Yeah, it was awful.”

I addressed Samuel: “You’ve changed. You used to be a chess champion.”

“Yeah, but now I’m a hipster.” Samuel nodded earnestly. Then he shook his head. “No. I forgot. I’m not meant to say that I’m a hipster. But I am one.” He bared his private-school teeth: they were straight and white like hers. “I got the braces taken off and everything! I was just waiting to get them taken off before I made my last exit to Hackney.”

Dear Vic,

A man with arrested development has invaded the house. If you don’t write back to me soon I’m going to kill myself. That is not an empty threat. I never did see the point in living unless some form of meaning was erected out of the raw, overwhelming nothingness. I guess that’s the point of being an artist. Are you an artist, Vic? Could you ever be one? I doubt it.

I’m glad. Artists are like megalomaniac aging despots who build halls of mirrors around themselves in order to block out the world that dares to be itself, e.g. autonomous. They veer between arrogance and insecurity.

I think I’m falling more and more in love with you.

Ann-Marie X

I sat in the basement on an upturned plastic bucket and switched on the projector. I had to cover my nose and mouth; the smell of sewage was unbearable. It was dark and I was alone except for the mice. We turned this space into a screening room a few months ago.

Our Super 8 installations flickered like sun on water. There I was dressed up in a mohair sweater and white shirt, my hair coiffed, my ankle socks pristine, preparing milk and cookies in a Formica kitchen, kissing two child actors whom Freddie had hired for the day, laying them down for a nap, duct-taping the bedroom door shut and sticking my head in the oven. There I was dressed up in an Edwardian hat, traipsing into the River Cam in the middle of the night, piling rocks into my pockets, looking depressed though ready. Drowning. There I was gassing myself in a parked car in a garage—that was Anne Sexton. She was less well known, but Freddie had wanted a trilogy. His lucky number was three, but only if pressed—really, he wasn’t superstitious at all. He’d won a young filmmakers’ scholarship from Sundance.

Dear Vic,

Do you want to Skype? My username is purposedestiny7.

Ann-Marie X

Samuel decided to make a cocktail called Aqua Fortis because a friend of a friend who’d been to Williamsburg had said it was deck, so off he went to Gerry’s specialist off-license in Soho to buy marjoram-infused Lillet Blanc, El Jimador Reposado, and Meletti Amaro. He returned hours later, empty-handed.

Samuel couldn’t get served. He couldn’t get served because he was only seventeen.

“Aren’t you supposed to be at school?” I demanded.

“I gave all that up.” He was standing against the wall in the kitchen, his hands behind his back.

Freddie sat at the table, morose and smoking.

“Samuel.” I spoke very slowly. “Do your parents know where you are?”

Samuel started to nod, but then he shook his head. I saw the tears. “They think I’m at the Custard—” Now the tears flowed.

“Is that your candy store?” I said.

“No. The Custard Collective is my squat. East. I ran away to the Wick, as they say!”

“They don’t say that,” I said. “I’ve never heard anyone say that.” I came very close to his face. “You are in a lot of danger. Hackney is a very dangerous place for a boy like you. They will get you.”

“I don’t care! I don’t care!” He went hysterical, grabbing at the copper pans hanging from the stove, banging them together. It reminded me of Allegra’s performance back in my dorm room all those years ago. Three years ago.

“Sit down!” I commanded.

He sat next to Freddie, who was repeating: “I want a drink. I want a drink.”

“I was born to be a DJ!” said Samuel, with passion. “Or a lifestyle—a style consultant.”

“Samuel’s an Enlightenment polymath,” said Freddie, darkly. “I’m going to make him a star.”

Samuel turned to Freddie with the light of true love in his eyes. He buried his face in Freddie’s neck and said again and again: “I’m sorry, sorry, sorry.”

I had agreed to buy the drink, but I had no intention of going all the way to Gerry’s because I was due in Soho in two hours anyway to start my shift. I considered trying to find Vic’s house after work and using Freddie’s drink money to pay him to go out with me. I had £150 in cash in my hand. I had never felt so free. But soon my freedom became a burden again.

I walked around the pond on Clapham Common, eyeing the men in tents. Their fishing rods trailed in the freezing water. A tree bent its gnarled body all the way over so that its branches disappeared in the depths. Yuppies walked their dogs despite the adverse temperature. One mongrel bounded toward a collie of some kind; they yelped at each other and then sniffed each other’s backsides in a circular dance of mysterious sweetness before their owners appeared in running gear and ruined the friendship. I passed the fenced-off zone where feral cats and feral children roamed. Like voyeurs at a peep show, young couples stared at sumptuous images of semidetached houses in the real estate agent’s window. The public housing buildings soared to the right, wrecking the dream. I passed the local crazy woman, parked outside Specsavers. She wore her hair in bunches and she carried a mangy Cabbage Patch doll. Her whole ensemble was bricolage.

I stopped and counted out fifty pounds. I gave it to her.

“I’ll tell you a secret,” she said. “It’s something I didn’t put in my memoir because they made me censor it when I had Betty.” She gestured to the doll.

I waited.

“Soon the snow will come. The snow will cover us.”

“Do you mean as in global warming?”

She shook her head. “No. I said snow. Not sun. It will freeze.”

“Do you mean the world or just in London?”

Her teeth were black. She rocked her baby and told me that I was a good girl, really.

“What do you mean, really?”

“Really,” she said. “Really you are.”

I headed to the only vintage shop in Clapham, which was also a coffee shop. Yuppies were sitting around with their iPads and their real babies. I decided not to use the money to pay Vic to go out with me. Instead, I bought a cream satin blouse with a pussy bow and a black pencil skirt, perfect for work, then headed over to Sainsbury’s and stocked up on Bio-Oil to counteract the aging effects of smoking. I bought a bulk pack of Golden Virginia too. I threw the rest of the money—seventeen quid—down the drain outside Snappy Snaps.

I had to go back to the apartment; I needed to get my ballet flats for work.

I tried to discern a sign in the clouds that meant Vic would definitely Skype me. But there was nothing. I saw a black cat cowering behind a trash can but it didn’t cross my path. I counted seven crowlike birds fighting over a scrap of food. But then another crow appeared. Eight is fucking useless to me. The grand old doors of the church where William Wilberforce had once preached against slavery were being shut and locked at just the moment that I tried to enter. I wanted to pray for Vic to text me. I got really excited when I passed the pond again and saw two white swans, their necks gracefully arched together, swimming in perfect symmetry. They looked utterly in love.

When I got closer, I realized that they weren’t swans at all—just two white plastic bags, floating aimlessly across the freezing water.

“Yah ’cause it’s a gay thing,” Jasper was saying, spread-eagled on the chaise longue, fondling one of Freddie’s uncle’s bejeweled daggers. “That’s why he wrote it. ’Cause he wanted this guy in, like, Copenhagen in the 1830s or something ridiculous. And the guy was like, no. I’m not a homo. I’m getting married. So Hans Christian Andersen was like, fine. I’m going to write a story about it instead and make, like, a shit load of money.”

“Who let Jasper in?” I demanded.

They were all dead drunk. Two empty bottles of champagne were standing on the painting of my face. The bust of Freddie’s uncle seemed to shake its head in horror. Samuel was as alabaster as Allegra now; he looked like he was going to be sick.

“Jasper,” I said. “Get out.”

“Ann-Marie, charmed to see you as always,” said Jasper. He tried to kiss me on the mouth but I blocked him. He stank of musk.

“I’m allowed to have friends over,” slurred Freddie. “We don’t have to live like fucking hermits in a cave anymore. Exams are over.”

“Yeah, so over. Hey.” Jasper had a widow’s peak. He had the frigid elegance of the international technocratic elite. “I’m so sorry to hear that you didn’t get your degree.” He tried to get his arm around my waist; again, I blocked him.

“It was a gesture,” I said. “Of emancipation.”

“Yeah right,” said Freddie.

“You only got a third!” I shouted at him. “Tell that to your fucking father, then see if he lets you curate a bloody show!”

“I think it’s fabulous,” said Jasper. “Artists shouldn’t have degrees. They should be renegades.”

“I’m not an artist,” I said.

“Yeah, what are you again?” asked Freddie.

“Oh, shut your mouth,” I told him.

Jasper collapsed onto the chaise longue. “So actually that cartoon is like a gay allegory. Because Hans was dreaming of being a human née heterosexual instead of a mermaid née queer in order to be, like, part of their world.” He swigged from his flute. “It’s about yearning.”

“I know about yearning,” said Samuel.

“So do I, so do I,” said Jasper. “I was yearning to smash Sebastian’s fucking face in last night when he started doing that preposterous whirling dervish dance.”

My heart stopped.

“Yeah, and she was there, clapping and shit.” Jasper looked at Samuel. “Your sister.”

“Shouldn’t hold a grudge, old man,” said Freddie.

“Was it a party?” I said.

“Yah.” Jasper grinned. “Ann-Marie, I’m surprised you weren’t invited.”

Freddie laughed.

“It was their going-away bash,” Jasper went on.

“Where are they going?” I said.

“Sebastian and Allegra are going to Mexico for six months to do some theater thing about Aztec sacrifice,” said Samuel in a rush. “Allegra’s going to rip out someone’s heart at the top of a pyramid and eat it.”

“Yeah, while Seb waits to ask her permission to use the toilet,” said Freddie.

The cigarette smoke in the room seemed to move inside my brain, fogging all thought.

Then I was striding over to the mantelpiece and crushing the seven brittle wishbones that I had saved and dried every time Freddie and I cooked Nigella’s roast chicken.