Читать книгу You Can't Get Lost in Cape Town - Zoe Wicomb - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

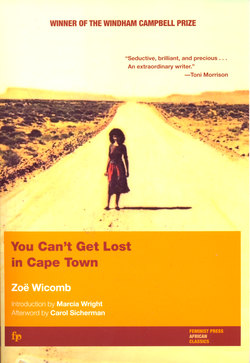

Although You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, Zoë Wicomb’s portrait of a young coloured1 woman’s coming to age in apartheid-ruled South Africa, spans the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s, this episodic novel is not a period piece. Indeed, to grasp the complex consciousness of those known in the twentieth century as the Cape Coloured people, one must reach back not just fifty years, but to a time far anterior to apartheid. What is more, this portrayal of one young woman’s life and expanding awareness is highly relevant to the present, when the struggle in South Africa is defined not by race-led laws but rather by class aspirations and economic disadvantages that carry forward a history of vulnerability.

Wicomb’s protagonist, Frieda Shenton, and her immediate family resolutely defy easy categorization, even when the characters themselves indulge in stereotyping. The Shentons are exceptional among coloured people in Little Namaqualand, an impoverished, semiarid area beyond the rich wheat farms and vineyards north of Cape Town. With respect to their neighbors, the Shentons are well educated and, invested in social improvement, proud of their growing command of the English language and of their patrilineal name-giver, a Scot. Frieda’s father, a primary school teacher, is recognized as a local notable, above the “commonality,” while Frieda’s mother has something more equivocal in her identity: Griqua parentage.2 Mrs. Shenton has embraced the ideal of the “lady” and continually warns her daughter against compromising behavior. The young and then mature Frieda must cope with and transcend essentially conservative anxieties that feed the stereotypes purveyed by her mother, which reveal a perspective prevalent among the coloured petty bourgeoisie. In telling Frieda’s story, Wicomb explores class, race, gender, and culture across a wide register.

LITTLE NAMAQUALAND

The social arena in Little Namaqualand into which Frieda is born encompasses a confusing array of identities. These identities fall short of being ethnicities, that is, coherent groups claiming a common ancestry. Rather, individuals carry or are assigned identities that may be fragments of their ancestry but bespeak stereotypical behaviors or features. A preliminary understanding of the roots of these various identities will enrich appreciation for Wicomb’s work, which restores coloured experience and history as it contextualizes, revises, and humanizes it. Wicomb does this on a personal scale, bringing forth characters who—albeit in sometimes oblique ways—comment on, align themselves with, or represent various indigenous and settler groups, ranging from the indigenous Namaqua to the coloured Griqua to the white Boers and British. You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town depicts not only the strong cultural hold of these identities but also their limits and shifting nature, as well as the painful history of colonization, displacement, and apartheid that accompanies them.

The Namaqua of Namaqualand were among the groups of Khoikhoi, the indigenous African pastoralists encountered by the Dutch in their initial settlements at the Cape in the mid-seventeenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Namaqua group of Khoi had yielded to the incoming Basters (literally meaning hybrid), mixed-race groups of frontierspeople.3 The absorbed Namaqua surface in Wicomb’s work through Skitterboud, the servant who figures in “A Fair Exchange.”

Of all these mixed-race frontierspeople, by far the most prominent were the Griqua, a group substantially involved in the nineteenth-century northward extension of Cape colonial culture. In the early 1800s, patriarchally led settlements of Basters moved north of the Orange River, beyond the limits of the Cape Colony, where they exercised greater political autonomy while seeking to maintain their economic and cultural ties to the Cape Colony. The name Griqua was adopted at one of the key settlements, Klaarwater, renamed Griquatown “because, ‘on consulting among themselves they found a majority were descended from a person of the name of Griqua’, that is, from the eponymous ancestor of the Khoikhoi clan, the /Karihur (‘Chariguriqua’).”4 The Griqua leadership and following continued to be materially oriented toward the Cape Colony, Christian and literate in aspiration, but hardly united among themselves. By the twentieth century, the Griqua had long passed their prime as frontierspeople. Some were dislodged from commercial sheep farming in the Orange Free State by white farmers. Others, in what became annexed as the northern Cape, were ultimately forced to emigrate east, extruded by the forces of capitalism and colonial authority that accompanied the exploitation of the diamond fields. A remnant of Griqua later journeyed to Little Namaqualand, where they added to a sparse, heterogeneous population occupying a space of very little economic potential.

Another identity that figures in the milieu of Little Namaqualand is that of the Boers, later called Afrikaners, who had been settling in this marginal environment from the eighteenth century onward. Boer was a term current before Afrikaner, but subsequently often used by the British to suggest a poor white element and a generally backward culture. Under apartheid, which specifically climaxed an Afrikaner Nationalist campaign to elevate their volk, Boers were regarded by the disenfranchised as a privileged group. Even as poor whites, they belonged to the political master class. For Mrs. Shenton, however, the word is still loaded with class distinctions; Boers lacked the refined quality of the more “civilized” British.

These identities and their accompanying stereotypes consolidated—particularly during the apartheid regime—in a brittle cultural and economic hierarchy, positioning Africans as the lowest group, with Indian and coloured groups then following, and privileging white European settlers. This hierarchy plays out, in overt ways, within given groups. Frieda’s coloured classmate Henry Hendrikse, for example, who has dark features and who knows the Xhosa language, is disparagingly referred to in the beginning of the work as “almost pure kaffir” (116). Later in the work, after black resistance has surfaced, Henry’s roots are not to be easily dismissed. Frieda’s acquaintance with Africans is slight, but she is presented as fascinated by the difference of indigenous people, who are distant and alien even as they occupy the same space. Henry Hendrikse remains an intentionally unclarified character, although evidently a “registered Coloured.”

In fact, for over a century, Western-acculturated Xhosa people had been settled in the northwestern Cape, brought in purposefully by the colonial authorities to serve as a buffer community against the raiding “Bushmen.”5 Other Xhosa immigrated in association with the London Missionary Society, and even more as workers on the railway and in the copper mines that had boomed and then failed in Little Namaqualand in the mid-to late nineteenth century.

It is worth recalling that from 1853 on, in the Cape Colony, civil rights were theoretically shared equally by men, regardless of race, if they were materially qualified. White legislators acted to stem the increase in the black electorate. One means was to build a dualism, with the Transkei as a native territory politically excluded from the rest of the Cape Colony. Even where the “colour-blind” constitution prevailed, the threshold of qualifications was raised, especially in the 1890s. In 1936, new enrollment of Africans ceased. The process of disenfranchisement would be completed under apartheid.

UNDER APARTHEID

You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town illuminates the interplay of these identities not only in Little Namaqualand but in Frieda’s expanding world. The novel, set and written during apartheid, also dramatizes how politically charged and changing these identities can be. Wicomb considers the ambiguous role of many coloureds, oppressed by whites and yet susceptible to the promise of state-granted privileges that guaranteed them protection from competition for employment from the even more oppressed Africans coming from desperate conditions in the Transkei and Ciskei of the Eastern Cape.

The barrage of apartheid legislation passed after the National Party came to power in 1948 aimed to achieve total segregation. One of the very first laws was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (1949). In 1950, in remorseless succession, came the Group Areas Act, authorizing racially exclusive areas of residence and removals to effect them; the Population Registration Act, categorizing all South Africans into four primary “racial categories”: “White,” “Coloured,” “Indian,” and “Bantu”; and the Immorality Act, prohibiting sex between the races. Clearly the ideologists aspired to control the most intimate relationships, leaving no sanctuary in private life. Anyone associating beyond the prescribed racial boundaries became criminalized.

In one of the most aggressive, explicitly political steps taken in the first years, the apartheid regime introduced a bill to exclude coloured voters from parliamentary constituencies in the Cape Province. The colour-blind franchise had legitimated an exaggerated sense of the “civilized,” as opposed to the uncouth or culturally “other.” Such a system of franchise had discriminated against unpropertied Boers, as well as ordinary coloured or African subjects. The determination to purge the non-white electorate, first by excluding the Africans and then disenfranchising coloured voters, had been an explicit program of certain Afrikaner Nationalists from the time of the unification of South Africa in 1910. Although the Cape franchise was constitutionally “entrenched,” requiring a two-thirds majority of the parliament to alter, that majority in the all-white parliament was achieved in 1935 for the purpose of disqualifying Africans on the basis of their race and ethnicity.

The proposed coloured exclusion precipitated a constitutional crisis; only in 1956 were parliamentary objections about the exclusion and judicial appeals defeated.6 Most politics had been urban based: the franchise issue would not have aroused the largely apolitical community Wicomb evokes in Little Namaqualand. Unlike Africans and Indians, before 1950 coloured people were not required to carry identity passes and, consequently, did not share in the attendant tradition of resistance.7 In the 1950s, however, the coloured population came under a similar administrative overrule, that of the Coloured Affairs Department, a parallel to the Bantu Affairs Department. The draconian combination of the Population Registration and Group Areas Acts circumscribed their freedom to own property within their province.

The Group Areas Act as implemented in the 1960s and 1970s displaced urban-dwelling people from historically mixed residential areas, to be confined in putatively homogeneous townships. During the thirty-four years from 1950 through 1984 in the Cape Province, only 840 white families were moved, compared with 65,657 coloured families.8 In You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town several episodes reflect the herding of people into coloured townships in Little Namaqualand. The references are somewhat veiled, but removals inflect the portrait of Auntie Truida in “Jan Klinkies” and the defeat that weighed on Mr. Shenton when he had to move, “to be boxed in” in a coloured village (29). In the book, this forced retreat is converted into a hope for the future when the small proceeds from the sale of the Shenton’s former home are invested in Frieda’s two years of education at an Anglican secondary school, enabling her to matriculate and move on to the University of the Western Cape (UWC).

In fact, the UWC would become a hotbed of Black Consciousness, a movement of young activists who had grown up under apartheid, led by such people as Steve Biko. Established under provisions of the Extension of University Education Act of 1959, the UWC was apartheid-defined as for coloureds only. Frieda is wry about the limited consciousness she possessed at the time of the boycott of memorial services for the April 1966 assassination of Prime Minister Verwoerd, who was, among other things, chief architect of the racially defined education system. Frieda suggests that the huddle of young men behind the school boycott was not deeply politicized.

In 1973 students suddenly exploded, moving away from the muted protest described in You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town. Black Consciousness developed the polarity of white versus black as the epitome of the struggle, and aligned Indian, coloured, and black South Africans in common struggle. UWC students bonded with their peers in other nonwhite universities, declaring on June 5, 1973, in their first major manifesto:

We reject completely the idea of separate ethnic universities because it is contrary to the historic concept of a university—that of universality—but are forced by the laws of the land to study at the [coloured] University of the W. Cape. . . .9

They pointed out the inequities in pay between white and coloured teaching staff and the overwhelming preponderance of white lecturers (seventy-nine) over black lecturers (twelve). They concluded that the institution was run by Afrikaners for Afrikaners, which is to say that it provided employment for Afrikaners who were Nationalist clients committed to the regime. In the first flush of radicalization, the UWC students rejected Afrikaans, although it was their mother tongue, in favor of English. Later thinking brought them to repossess Afrikaans as a language of liberation.10

Frieda’s love affair with the English language and literature is her passport to the wider world, specifically Britain. Living in Britain from 1972 to 1984, she is removed from the main cut and thrust of the confrontations of students and of an increasingly aroused populace with the enforcers of apartheid.

The egalitarian stance of the UWC manifesto might have rooted the students in a tradition of South African political dissent that advanced equality and unity, as manifested, for example, by the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM), which since 1943 had followed a Marxist line independent of the South African Communist Party. A movement attractive to schoolteachers, it had recruited a few Indians, Africans, and whites, as well as coloureds. A revived Unity Movement, however, failed to capture the mood of the times. The students drew on Black Consciousness. The movement contained elements of spontaneity, impatience with structural analysis, intolerance of compromising elders, and great heroism. Black became a metaphor for nonwhite, a very suitable one for a struggle against the white racist regime.

When in 1983 a new Tricameral Parliament provided for a separate chamber where coloureds would legislate on their “own affairs,” several parties offered candidates. The strongest was the Labour Party, essentially the voice of the most skilled and organized coloured labor unions. Coloured voters stayed away from the polls in these elections, which extended franchise to coloured and Indian voters but excluded Africans. Many coloured voters were made aware by the active campaign of the United Democratic Front (UDF) of the falsity of democracy when racial segregation remained intact.11

Frieda returns from Britain after a twelve-year absence still politically naïve, as are most of her friends (with the exception of her friend Moira) and certainly her family, who are still defined by their localities and histories in South Africa. She encounters once again the depth of coloured acquiescence.

Wicomb published this book originally in 1987, three years before the end of apartheid, while state violence and insurrection were at a height. Close readers of You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town at that time would have been cautioned and perhaps less surprised than many political observers when, in the months before the 1994 general elections, the coloured voters moved from “undecided” to support of the National Party, which courted them as part of an enlarged constituency of Afrikaans-speakers. They delivered the Western Cape provincial government to the old Afrikaner ruling party, while in most other provinces the African National Congress swept the elections. Peter Marais, one of the victorious candidates, wrote of his personal sense of identity:

My language, Afrikaans, provides the first indication of where I am located because many things flow from language. My religious affiliation is another feature of my identity. . . . As a bruin man (brown man) of Griqua and Afrikaner descent, I do not wish to have another “bruin man” telling who I am; or that I am nothing. On the contrary, I am something. I am a Griqua with Afrikaner blood.12

It is apparent from such a testimony that Griqua in the new South Africa was becoming an ethnicity around which to mobilize. The eventual political alliance of Griqua cultural chauvinists, however, is not a foregone conclusion. In the last chapter of the novel, Wicomb dramatizes this shift in perspective; the Griqua suddenly enjoy a more positive valence. Wicomb questions the politics of ethnicity as much as the rigid racism of apartheid.

RESPECTABILITY AND COLOR

At the heart of the ambiguity for coloured peoples are the implications of their mixed ancestry and two sorts of prejudice: prejudice against them because of color and prejudice against such women in particular as (presumptively) available for sexual liaisons. These markers are inflected differently across time and circumstance.

Mixing in the seventeenth century occasionally involved visible and highly placed persons. Detailed examinations are now being made of the life of the late-seventeenth century Khoikhoi woman Eva, the protégé of and interpreter for the first Dutch governor, wife of a company official, and, finally, a mother in reduced circumstances. Her Khoi name, Krotoa, is adopted by those who promote her as the foremother of the new South Africa.13 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some other marriages between white men and Khoi or coloured women were solemnized in church. A few descendants of these marriages became citizens, burghers, with full civil rights.14 For example, among the leadership in colonial coloured resistance was the Reverend James Read, Jr., the son of a London Missionary Society missionary and a Khoi-descended woman.15

That the Dutch East India Company imported and owned slave retainers whom it housed collectively in Cape Town, however, created a very different situation. Cape Town has been called “the tavern of the two seas,” the port where vessels bound for or returning from the Far East called for provisions and respite. The slave lodge became a place to find partners in casual sex and children were born with anonymous fathers, some of them European sailors. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, German soldiers brought in as mercenaries by the Dutch East India Company added to the mixture by making country marriages. By the time the British took over the Cape Colony in 1808, “free people of colour” were of many shades. There were a number of slaves of mixed parentage, and increasing ambiguity as to whether the “tame Hottentots”—Khoi within colonial society or grouped around mission stations—were melting into the same category. With the abolition of slavery and other degrees of formal servitude, the process of acculturation accelerated. In the Cape Colony, the civil rights of free people were equal. Contracts between masters and servants, however, put the servant in a weak position. And most coloureds were servants. On farms, with arrangements dating from the days of slavery, the domestic privacy of laborers’ families was minimal. The Cape Marriage Order of 1839 provided for the regularization of marriage and induced a flow of couples to the churches.16

An example of deep prejudice within colonial society has been given by Pamela Scully through the case of Anna Simpson, the wife of a laborer who in April 1850 brought rape charges before the circuit court. The defendant confessed and was sentenced to death, only to have the sentence commuted because of white citizens’ protests that Anna Simpson was coloured: “The woman and her husband are Bastard coloured persons, and that instead of her being a respectable woman, her character for chastity was very indifferent.”17 On the score of respectability, in the eyes of white moralizers, women of color were lacking unless proven otherwise.

The impoverishment of the majority of those considered to be coloured resulted from their lack of capital and ability to secure and retain land, their indebtedness, and the failure of wages to rise in real terms. It has been reckoned that pay for coloured workers did not improve relative to the cost of living between the 1840s and the interwar period.18 There may have been some real increases in the 1940s and 1950s, but they were stalled and reversed as the full effects of apartheid took hold. Coloured wages declined steeply relative to white wages. Declining real wages affected women as well as men in the formal economy; women had to work ever harder, by whatever means, to meet their household needs. The attitude of the canteen worker Tamieta at the University of the Western Cape in “A Clearing in the Bush” reflects many women’s aversion to the risk of lost employment, as well as compromises of respectability.

The Population Registration Act was one of the most painful measures for coloureds. Each person had to carry an identity card declaring her or his race category. Entitlement to educational facilities, to residential areas, to employment, to association all followed. When the Population Registration rubrics were dictated, “Coloured” subcategories distinguished “Cape Coloured,” “Cape Malay” (Muslims), “Griqua,” and “other Coloured.”19 These reflected potential fault lines to exploit in a policy of divide and rule. But the overarching categories “Coloured,” “European”(or “White”), “Bantu” (African), and “Asian” (or “Indian”) served as racial cyphers for juridical purposes. Members of the same families received different racial classifications. Assignments could be altered each year, unilaterally by officials or following appeal. In 1970, for example, the Ministry of Interior unilaterally reclassified seven persons from “Coloured” to “Bantu,” and acted favorably on petitions in twenty-two cases to be changed from “White” to Coloured,” twenty-three from “Coloured” to “White,” and fourteen from “Bantu” to “Coloured.” Race Classification Boards reclassified one “White” to “Coloured,” four “Coloured” to “White,” and twenty-nine from “Bantu” to “Coloured.” The report does not specify where in South Africa these persons resided.20 From Wicomb’s writing, readers will appreciate that consciousness of race and cultural status was sharply registered within the ranks of coloureds. Mrs. Shenton’s ironic reference to the chauffeur’s possible legal status as a “registered Coloured” bespeaks her uncertainty over the identity of the apparently white driver (4).

A case that drew great attention to the excruciating consequences of population registration was that of Sandra Laing. Laing was the daughter of poor but “respectable” whites, whose features did not conform to the Caucasian model. She was dismissed from her white school and reclassified “Coloured” by officials. On protest and following a court case, she was reclassified “White,” but never again settled into her privileged entitlements. She finally married an African.21

These notes will have underscored the irony of Wicomb’s title. You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town comes from a confident statement by Frieda’s longstanding white boyfriend as she is about to go off to have an abortion in the white part of the city. Frieda Shenton, for her part, does not have a sense of direction, even though she ends up in the clinic and is able to deny that she is coloured in order to have the procedure. What is wonderful about this character is her unwillingness to follow in the tracks of others, her observance of the humanity of her own extended family and members of Namaqualand society regardless of her mother’s indoctrination and projection of them as dangerous, throwbacks to poor, uncultured antecedents. The important reconciliation that appears at the book’s end reminds us most tellingly of a general point of the work—that rehearsed, constraining histories can be transcended, at least momentarily.

Marcia Wright

New York

December 1999

NOTES

1. Coloured, a term referring to mixed-race individuals in South Africa, is discussed with more texture later in this introduction. In the context material for this edition of You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, coloured appears, for the most part, without quotation marks and an initial capital. Cape Coloured has been capitalized as a historical marker; similarly, when the term denotes the specific apartheid classification named in the Population Registration Act of 1950, it appears with an initial capital and in quotations. In an essay on shame and identity, Zoë Wicomb briefly comments on the changing use of the term coloured, especially with respect to apartheid and liberation politics. She writes, “Such adoption of different names [i.e., black, “Coloured,” Coloured, etc.] at various historical junctures shows perhaps the difficulty that the term coloured has in taking on a fixed meaning, and as such exemplifies postmodernity in its shifting allegiances, its duplicitous play between the written capitalization and speech that denies or at least does not reveal the act of renaming” (“Shame and Identity: The Case of the Coloured in South Africa,” in Writing South Africa: Literature, Apartheid, and Democracy, 1970–1995, ed. Derek Attridge and Rosemary Jolly [New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998], 93–94).

2. Griqua, an ethnicity among coloured South Africans, is a designation and political identity treated later in this introduction.

3. J. S. Marais, The Cape Coloured People, 1652–1937 (1939; reprint, Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1968), chap. 3. The other classic study is W. M. Macmillan, The Cape Colour Question: A Historical Survey (1927; reprint, London: Hurst, 1968).

4. Martin Legassick, “The Northern Frontier to c. 1840: The Rise and Decline of the Griqua People,” in The Shaping of South African Society, 1652–1840, ed. Richard Elphick and Hermann Giliomee, 2d ed. (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1989), 382. Such distillations of one trace element from a number of sources (in this case, the naming of a common ancestral link) is, of course, part of ethnicity-building, as a vigorous literature on the invention of tradition makes clear.

5. Marais, Cape Coloured, 85. Poppie Nongena is a poignant example of an acculturated, Afrikaans-speaking woman of the Western Cape; see Elsa Joubert, Poppie Nongena (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985).

6. Thomas G. Karis and Gail M. Gerhart, introduction to Challenge and Violence, 1953–1990, vol. 3, From Protest to Challenge: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882–1964, ed. Thomas G. Karis and Gwendolyn M. Carter (Stanford: Hoover Press, 1977), 10–11.

7. A Western Cape woman who married a “Bantustan” citizen from the Eastern Cape lost her rights of residence. This situation is powerfully reflected in Joubert’s Poppie Nongena. The account of Poppie’s experiences working in fish processing factories on the west coast of the Cape Province, not far from the interior of Little Namaqualand, opens the opportunity for reflection on underclass women’s lives as compared with the aspirant, precarious middle class explored by Wicomb.

8. Elaine Unterhalter, Forced Removal: The Division, Segregation and Control of the People of South Africa (London: International Defence and Aid Fund, 1987), 146.

9. Thomas G. Karis and Gail M. Gerhart, eds., Nadir and Resurgence, 1964–1979, vol. 5, From Protest to Challenge: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882–1990, ed. Thomas G. Karis and Gail M. Gerhart (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1997), 525.

10. Ibid., 103.

11. Bill Nasson, “Political Ideologies in the Western Cape,” in All, Here, and Now: Black Politics in South Africa in the 1980s, ed. Tom Lodge, Bill Nasson, Steven Mufson, Khenla Shubane, and Nokwanda Sithole (New York: Ford Foundation, 1991).

12. Peter Marais, “Too Long in the Twilight,” in Now That We Are Free: Coloured Communities in a Democratic South Africa, ed. Wilmot James, Daria Caliguire, and Kerry Cullinan (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1996), 60.

13. See, for example, Julia Wells, “Eva’s Men: Gender and Power in the Establishment of the Cape of Good Hope, 1652–74,” Journal of African History 30(1998): 417–37, and Yvette Abrahams, “Was Eva Raped? An Exercise in Speculative History,” and Christina Landman, “The Religious Krotoa (c. 1642–1674),” Kronos: Journal of Cape History 23: 3–21, 22–35.

14. Richard Elphick and Robert Shell, “Intergroup Relations: Khoikhoi, Settlers, Slaves and Free Blacks, 1652–1795,” chap. 4 in The Shaping of South African Society, 1652–1840, ed. Richard Elphick and Hermann Giliomee, 2d ed. (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1989).

15. Timothy Keegan, Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1996), 238. See also Robert Ross, “Missions, Respectability and Civil Rights: The Cape Colony, 1828–1854,” Journal of Southern African Studies 25 (September 1999): 333–45.

16. Pamela Scully, Liberating the Family? Gender and British Slave Emancipation in the Rural Western Cape, South Africa, 1823–1853 (Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1997), 116, 127–28.

17. As quoted in Scully, Liberating, 155–56.

18. Marais, Cape Coloured, 266.

19. Apartheid: The Facts (London: International Defense and Aid Fund, 1983), 16. The original default category “Coloured” also included “Indian,” “Chinese,” and “other Asiatic.”

20. Muriel Horrell, et al., comp., A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1971, vol. 25 (Johannesburg: Institute of Race Relations, 1972), 60.

21. W. A. de Klerk, The Puritans in Africa: A Story of Afrikanerdom (London: Rex Collings, 1975), 268–70. De Klerk, a maverick Cape Afrikaner writer, criticizes the apartheid regime and makes a major point of the case of Sandra Laing as one evidence of the absurdity of the system. A docudrama, The Search for Sandra Laing (video: 50 minutes, color, ATV production in affiliation with the African National Congress, 1978; distributed by IDERA, Canada), provides a searing reenactment of the story.