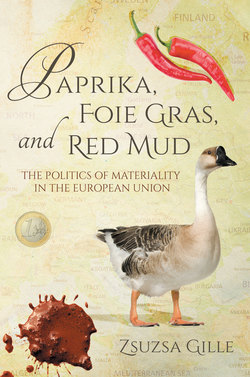

Читать книгу Paprika, Foie Gras, and Red Mud - Zsuzsa Gille - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PICTURES OF AN ACCESSION

ОглавлениеI was first nudged in this direction of inquiry when I noticed a curious contradiction. Take a look at the iconography of the European Union. On the Euro banknotes, what dominates are images of architectural apertures: gates, windows, bridges.8 The front side of the Euro coins display stylized cartographic images of Europe and in some cases other parts of the globe next to Europe.9 Above the map of Europe float the twelve stars arranged in a circle—the EU’s symbol—creating a halo effect that also expresses an idea of unity: all these once belligerent nations joined under one (starry) sky. The European Union’s self-representation shows a strong resemblance to the pictures associated with globalization. Google’s image search for the term “globalization” yields a predominance of pictures of the globe itself, with various icons of flows, networks, and brands superimposed on them. Such cartographic images juxtaposed with symbols of connectedness express a certain desire, if not promise, of a particular type of freedom. This is the freedom that results from transcending time and place, mostly the latter: a metaphorical liftoff from the ground, specifically the gritty, bumpy terrain of localities and nation-states and the physical constraints of the particular—altogether a freedom from matter.

“Will pig slaughter conform to EU laws? Yes.” A poster encouraging Hungarians to vote in favor of Hungary’s accession to the European Union in the 2003 referendum.

“Can we keep eating poppy seed dumplings? Yes.” A poster encouraging Hungarians to vote in favor of Hungary’s accession to the EU.

“Can I open a pastry shop in Vienna? Yes.” A poster encouraging Hungarians to vote in favor of Hungary’s accession to the EU.

Yet when Hungary and Romania were about to join the European Union—in 2004 and 2007, respectively—the images that accompanied these momentous events were of a strikingly different type. One set was presented on the posters encouraging Hungarians to vote affirmatively on their country’s EU accession in the 2003 referendum.

What is the message of these posters? At the very least we can say that there was an intention of humor or at least levity, as was the case in the other official pro-EU campaign materials, pamphlets, TV shows, and ads. The humor in the official materials, however, was interpreted as poking fun at, if not ridiculing as trivial, certain concerns about EU membership. Worries about foreign land ownership, labor mobility, or the future of national culture were certainly legitimate and were often raised, but officials rarely if ever responded to them in public with factual arguments. From my observations of the campaign and of the debates on various Internet fora prior to the referendum, it became clear that rational discussion or deliberation was never the intention of elected officials and the experts working on the accession. Nor could this have happened, since the information on which to base arguments was unavailable even to the most engaged citizens. The text of the agreement between Hungary and the EU that contained the conditionalities of the country’s membership, several hundred pages of legalese, was not even publicized—if by that one means posted online—until a few days before the referendum.

Another aspect of these posters, however, is more significant: the overwhelming food imagery and concerns about various EU regulations concerning the safety, quality, and ethics of commodities (yes, including that of condoms).10 This was certainly contradictory to my expectations. The European Union, and before it the European Community, has always argued that its main objectives are to prevent another war in Europe and to promote democracy and human rights. That is, the EU is supposed to be about big and lofty things, not little and mundane ones like sausage or poppy seed dumplings. The benevolent interpretation of the campaign’s focus on the latter is that officials were trying to address concerns about the future of Hungarian agriculture head-on, since those were the ones most often voiced by both skeptics and opponents of the accession. But even the question about capital mobility—“Can I open a pastry shop in Vienna?”—used food-related imagery (a slice of pastry), which suggests that the creators of the campaign thought it a winning strategy to associate the EU with appetizing pictures, rather than with symbols of democracy or, in the case of capital mobility, with images of money and wealth. Is this because the Hungarians who needed convincing the most were likely to be more concerned with their bellies than with abstract civilizational values or entrepreneurial opportunities? While this might have characterized some of the campaign architects’ thinking, this is only a partial answer. To understand what else might have been at work in the iconography of the referendum campaign, let us look at a second set of images.

Most of these pictures come from images circulated in Hungarian and Romanian cyberspace. Many of them were in a slideshow distributed on the eve of Romania’s joining the EU (2007), bearing the title “Europe, here we come.” Others are from Hungarian web pages abounding with self-deprecating photos of the state of Hungarian society. Many capture the lack of intelligence of their compatriots or just the sheer absurdity of everyday life in a society where people try to muddle through.

(above and facing) Images from a slideshow titled “Europe, here we come” circulated on the web before Romania’s EU accession.

While the imagery of the Hungarian EU campaign represents a certain official version of the story of accession and as such is, so to speak, from above, and the second set of images contained in the virtually disseminated slideshow is unofficial and generated from below, they both stand in contrast with the EU’s self-representational iconography. These respective figured worlds epitomize a number of opposing values and ideas:

| big | small |

| ideal, ethereal | material |

| flow, connection | blockages, frictions |

| gaze from above | gaze from below |

| opening | closing |

| unity, order | discrepancy, chaos |

| magnanimity | small-mindedness, pettiness |

| juncture, seamlessly sutured | gap |

Why do the EU’s self-representional images stand in such striking contrast with the Hungarian (and Romanian) representations of the two countries’ relationship with the EU? It is certainly not the case that the former set expresses a pro-EU while the latter two an anti-EU stance. This is true as much for the official poster campaign as it is for the slideshow. The latter, after all, pokes fun not at the EU but at an eastern Europe that is still too messy, too stupid, and too poor to become truly European; this is an obvious endorsement of the European project.

It might also be appealing to treat the former as representing something universal and ideal—a kind of model—and the latter as revealing the inevitable messiness of its implementation—a local muddle. This association—of the universal with the ideal, the abstract, and the immaterial, and of the particular with the less-than-ideal, the problematic, the unintended consequence, and the embarrassingly material—is so natural because it is endemic in a particular though hegemonic epistemology. In this perspective a series of binary terms overlap:

| macro | micro |

| global | local |

| whole | part |

| abstract | concrete |

| universal | particular |

The implication for social science scholarship is that studying micro-level phenomena, especially in a particular locality, can only yield partial and particular stories, and in order to understand the universal features of, let’s say, capitalism or the European Union, we have to conduct research at the macro or global scales.

In that vein the social science scholarship on postsocialism and the Eastern Enlargement of the EU (the term referring to the admission of ten former socialist countries in 2004 and 2007) has either focused on macro- and global-level developments such as treaties, or studied how candidate and later member states measured up with regards to accession criteria and with each other. The more qualitative studies tended to be case studies that were implicitly written off as particular cases of democratization, privatization, and EU accession with the argument that they revealed the bumpiness of the road to capitalism, democracy, and the EU. They were thus inadvertently interpreted as particular and admittedly idiosyncratic variations on a universal theme. While to my knowledge there is no formal social science study of the three cases that make up the empirical backbone of this book, this epistemology would reduce any such case to concrete and unique features of these transformations and, as such, dismiss them as not truly adding anything relevant to the “big picture.”

Instead of taking them to be examples of the particular qua local, I read the contradiction between these two sets of images, and their attendant list of binaries, as evidence that what we need is a new reading of the postsocialist transition and EU accession. Two metaphors have been helpful in understanding these processes. Both have been productive but also selective in terms of what type of analysis they made possible. One is the metaphor of tabula rasa, the other is “fuzziness.”

Early observers of the postsocialist transition noted that the attendant transformations—democratization, privatization, marketization, Europeanization—did not take place on a tabula rasa.11 What they meant to convey by invoking the blank slate metaphor is, first, that building a new type of society does not take place in a vacuum, nor can it commence from scratch; people of the future are people of the past, and short of brainwashing them, you will have to build democracy not with the people you want but with the people you have. Not only can one not just purge everything in the course of transition itself, but the local social and cultural conditions will also affect the emerging nature of capitalism and democracy. These arguments were developed and demonstrated in dozens of brilliant studies of land reform, labor relations, and civil society conducted in all the formerly socialist countries.

Perhaps the most paradigmatic concept is Katherine Verdery’s (1999, 2004) term “fuzzy property.” In analyzing land restitution and privatization in postsocialist Romania, this brilliant and influential anthropologist has shown that private property cannot emerge as a fully formed legal concept that captures reality in unambiguous terms. The practical tasks of what is called privatization often seem insurmountable, and in order to manage day-to-day reality, compromises and temporary solutions have to be made, with the result that property boundaries become blurry and the identities of the owners themselves are also obfuscated. Most social scientists have stopped at documenting the difficulty of imposing markets and democracy, but a few have seen such problems and even chaos as signs of resistance, with the suggestion—more often implicit than explicit—that one cannot prejudge the outcome of postsocialist transitions and that such transitions—especially because they are more imposed than homegrown—will generate new conflicts and inequalities that advisors to the new regimes ignored or promised to be short-lived.

These studies were path-breaking and have not only contributed tremendously to our understanding of this “Great Transformation,” but have also laid the foundation of what is now a legitimate and respected interdisciplinary research field, postsocialist studies.12 Standing on the shoulders of such giants, it is now possible to see a new horizon for this scholarship, one that re-examines and complicates the global-local and universal-particular matrix. Let me explain why this is necessary, starting with the metaphor of the tabula rasa.

The image the concept of a blank slate conjures up is one of painting or writing on a clean, white surface. Certainly the end of state socialism and the subsequent entry into the European Union were radical and swift enough to be compared to “painting over” the old regime, and social scientists studying eastern Europe were correct to question how clean that slate could really be wiped. The previous writing or picture showing through—as if in an Etch A Sketch toy—were primarily seen as obstacles preventing the imposed new writing or painting from appearing clear and legible. They made the new picture fuzzy.

This fuzziness, however, does other work besides serving as an impediment. To understand this we may want to reach to another metaphor, one that recognizes that the transition and transformation in postsocialist countries were never intended to replace old with new in a static fashion, but to lift the old and move it in the same direction as the new. The slate image suggests stasis; once it is covered with the new writing or painting it stays so. In contrast, when a country joins the “free world” or the EU it acquires a new direction, a new type of movement, a new mode of change. In fact, movement—in this context most call it progress—is expected and is the stated reason for the change. So a metaphor that implies movement might be more useful for our purposes. I suggest we think of driving a car. In order for a car to be able to move there has to be friction: the asphalt should have a sufficiently rough surface and the tires should have deep enough grooves for movement to occur. Smooth surfaces—think of icy highways—only result in slipperiness, and the car will not be able to move, certainly not in the desired direction. Going back to the slate metaphor, it is not just that you cannot wipe the slate completely clean ever, as postsocialist studies suggested, but that it is not desirable to do so. Some previous writing must show through or some surface friction must remain for “progress” to occur. At the same time, too rough a surface will present greater resistance to movement. The conundrum of EU integration is not whether there should be an attempt to wipe the slate clean—to eliminate everything old—but how much of the previous writing should remain, or, in the new metaphor, how rough the old surface should be for (the right type of) movement to occur.

An example will help illustrate this. In my previous research on industrial waste, I argued that to the extent that the EU’s waste policies prioritized reuse and recycling, they could have “latched onto” Hungary’s socialist-era waste collection and recycling infrastructure and policies. Instead, to fulfill other EU accession requirements laid down in the Copenhagen Criteria, such policies and infrastructure were seen as state intervention in the economy and, as such, something that interferes with markets and private property. So all such policies and practices had to go. After more than a decade of a veritable free-for-all for waste generators—whether in industry or households—it was now much more difficult to reintroduce a modicum of material conservation, which now had to be implemented within a ten-to-fifteen-year derogation period after accession. This is one case in which allowing the previous “writing” or “picture” to stay, or—to use my newer metaphor—not polishing down the old surface completely, would have allowed not only a smoother transition to the EU’s waste prevention and sustainability policy paradigm, but would have eliminated the damage caused by an interim with neither old nor new regulation. It is in cases such as this that Kristin Ghodsee’s (2011) use of another metaphor for the postsocialist transition makes a lot of sense. Quoting her research subjects, she likens the radical transformations in post-1989 Bulgaria to a situation in which one demolishes one’s old house before finishing construction on the new one, thus leaving one figuratively, if not literally, homeless.

Indeed, the pictures in the Romanian slideshow in particular demonstrate not so much fuzziness or old pictures showing through, but friction, lack of movement, and dysfunction resulting from incongruity. The same is true for my three cases. The balconies cannot be fully used because of the lamppost poking through their floors (which also creates a safety issue); the newly paved sidewalk cannot be walked on; and the slide ending in the dumpster is not useable as play equipment nor can it fit in the dumpster fully, preventing its functioning both as value and waste.

My use of the metaphor of friction adapts Anna Tsing’s (2005) image to a new context. She uses “friction” to show that, far from being a smooth movement of people, money, knowledge, and goods, globalization—like any movement, according to physics—requires a certain resistance of the surfaces and entities brought into contact. Such interactions are productive, not just in the sense that they provide traction for things on the move, but also in the sense that it is from such awkward encounters that culture is generated. Friction is also unpredictable: in one case it may end up providing the much-necessary traction, a surface for something slippery to hold onto; at other times, as Tsing says, it can inspire insurrection, so that the physical concept of resistance manifests in actual social resistance.

Tsing faithfully references the physics of friction, and her research does attend to nature and materiality. Yet her examples of friction are drawn mostly from the realm of culture, knowledge, and identity, and less often from the realm of objects. It is in the spirit of inspiration that I want to adopt and direct this concept back to its original milieu: the material. The case studies in this book demonstrate that the EU is a sociomaterial assemblage, and that when a new member country enters this assemblage, its existing materiality and practices rub against those of the western European countries, whose practices have shaped and constitute the EU. Physics tells us that two further things happen as a result of friction in addition to generating movement—the effect that Tsing pays attention to. In some cases there is a triboelectric effect: an explosion. An example is striking a match. In other cases, over a longer time period, there can be a polishing effect; just think of sanding a piece of wood. Rubbing wood with a piece of sandpaper will ultimately wear down both surfaces—though to a different degree—so that traction and grittiness decrease. This is the opposite of explosion. It is a certain kind of stabilization.

The literature on EU legal harmonization has tended to assume the second effect: stabilization and normalization, a slow, steady, relatively uneventful polishing effect. The paprika panic, the foie gras boycott, and the red mud spill, however, are of the former kind. In them the friction becomes too much, there is an explosion and things come to a halt. In the crater the detonation leaves behind, the pieces may be picked up again, but they will never be reassembled in quite the same way.

When we look at globalization, the postsocialist transition, or EU integration through the lenses of triboelectric effects rather than movement or polishing, different connections will become visible. How to study these cases is what I turn to next.