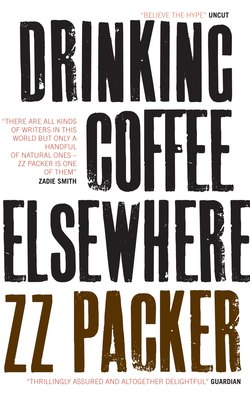

Читать книгу Drinking Coffee Elsewhere - ZZ Packer - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOur Lady of Peace

THE CHROME-TOPPED vending machine in the Baltimore Travel Plaza flashed Chips! Chips! Chips! but no one could have known it was broken unless they’d been there for a long time, like Lynnea, having just escaped lackluster Kentucky, waiting for a taxi, watching a pale, chain-smoking white girl whose life seemed to be brought to a grinding halt by an inability to obtain Fritos.

The white girl kicked the vending machine, then cracked her knuckles. After a few spells of kicking and pouting, she found her way to the row of seats where Lynnea was sitting, then plunked down next to her.

“I’m going to kill myself,” the white girl said.

Lynnea turned in the girl’s direction, which was invitation enough for the girl to begin rattling off the story of her life: running away, razor blades, ibuprofen; living day to day on cigarettes and Ritz crackers.

Outside the Travel Plaza, Baltimore stretched black and row-house brown. Traffic signals changed, dusk arrived in inky blue smudges, and slow-moving junkies stuttered their way across the sidewalk as though rethinking decisions they’d already made. This, she thought lamely, had been what was waiting for her in Baltimore.

But any place was better than Odair County, Kentucky. She’d hated how everyone there oozed out their words, and how humble everyone pretended to be, and how all anyone ever cared about was watching basketball and waiting for the next Kentucky Derby. Her grandparents had been born in Odair and so had their parents. Her family was one of four black families in the county, and if another white person ever told her how “interesting” her hair was, or how good it was that she didn’t have to worry about getting a tan—ha ha—or asked her opinion anytime Jesse Jackson farted, she’d strangle them.

Nevertheless, she’d gone back to Odair County after college and started working at the Quickie Mart. One night—while in the middle of reminding herself that the job was beneath her, and that once she’d saved up enough, she’d move to a big city—four high school boys wearing masks held up the place with plastic guns, taking all the Miller Light they could fit in their Radio Flyer wagons. She hadn’t been scared, and the manager had said she’d done the right thing. Still, she smoked her first cigarette that night, and spread a map of the country over her mother’s kitchen table.

When she’d ruled out the first tier of cities—New York (too expensive), L.A. (she had no car), Chicago (she couldn’t think of any reason why not Chicago, but it just seemed wrong)—Lynnea had settled on Baltimore. She took an apartment sight-unseen, her last few hundred dollars devoured by a cashier’s check for a security deposit, signed to a landlady named Venus.

Now that she had arrived in Baltimore, she’d begun to have doubts. There was no taxi in sight, and the white girl next to her droned on, describing preferable methods of suicide.

“Tibetan monks light themselves on fire,” the girl said.

Lynnea held her head in her hands and tried to ignore the girl. She stared at the floor, its checkered tiles marbleized by filth; she looked outside to see if any taxis had arrived. She even cast her eyes about the bus station crowd, but the white girl still would not shut up.

“Eskimos kill themselves by floating away on icebergs,” the white girl said.

“If you can find an iceberg anywhere near Baltimore,” Lynnea finally said, “I’d be glad to strap you to it.”

HER LANDLADY, Venus, was a tiny sixtyish woman who walked in quiet, jerky steps. Her complexion was the solemn brown of leatherbound books—nearly the same shade as Lynnea’s—but atop her head, where presumably black hair should have been, Venus wore a triumphant blond wig. Lynnea had been living in a damp efficiency below Venus for nearly three months when she spotted the woman taking out the garbage, readjusting her wig as though Lynnea were an unexpected guest.

“Oh my. Shocked me near to death. How’s the moving going?” “I moved in three months ago,” Lynnea said. “I’m pretty much finished moving in.”

“I thought you were moving out.”

“No. Not that I know of.”

Lynnea always paid her rent late and hadn’t paid last month’s at all. She slurped black bean soup straight from the can, used newsprint for toilet paper, had tried foreign coins and wooden nickels in the quarters-only laundromat. By the end of three months she’d decided freelancing at the weekly paper was not enough; she would need a job that paid for dentist visits, health insurance, toilet paper.

Then she read about a teaching program that promised to cut the certification time from two years to a single summer. This, she knew, was for her. Inner-city Baltimore students would be nothing like the whiny white girl from the bus station. Lynnea would become an employee of the city, and have—at long last—benefits.

“We’re going to do a few exercises,” the director said on the first day of the certification program. “What you’re trying to do,” she said widening her eyes, “is disappear.”

Lynnea waited for her to explain what she meant by “disappear” but the director just smiled as though disappearing were easy and fun. Lynnea looked around the classroom to see if others were as lost as she. A man who had previously introduced himself to Lynnea simply as Robert the Cop stared at Evelyn, then winced as though he’d been asked for a urine sample.

“Miss Evelyn,” Robert the Cop said, his hands holding a box of imaginary no-nonsense. “I’m a cop. I’m new at this teaching business. You gotta break it down for me. What do you mean by ‘disappear’?”

“Disappear. You know. To go away, to vanish.”

Lynnea sighed and looked down, watching a roach scramble across the floor. Then Jake Bonza, the man second-in-charge, a teacher for twenty years, took over. “What Ms. Evelyn Hardy means is this: one a y’all is going to pretend to be the teacher. The rest of y’all are going to abandon your adult selves and act like students. Not the goody-two-shoe students, but the kinda fucked-up students you know y’all were or wanted to be.” He paused, looking at them as if to sear his words into their heads before he continued, “This’ll prepare you for the freaks of nature who’ll throw spit wads at you while you try to take attendance.”

Bonza browsed the room, flashing an ornery grin. “Yeah.” He nodded. “We’ll see which one a y’alls cracks and bleeds. Which one a y’alls bends over and takes it from behind.”

DURING THE training sessions, adults playing students took their roles as miscreants to heart: they got out of their seats, wanting to pee and eat and smoke: Robert the Cop stood and lit a Marlboro while some pink farm girl from Vermont went through her lesson on subtraction in tears, her shaky hand gripping the chalk so hard it broke. They’d ask questions like how much wood could a woodchuck chuck; one teacher felt liberated enough to discharge a sulfurous fart. Lynnea sat with her chin resting on her desk, eyes trained on the chalkboard, refusing to believe her students would act this way, refusing to participate in team-spirit badness.

But after eight weeks of role-play, Lynnea was in front of a real classroom. Freshman English. After she’d written her name on the chalkboard, a tall boy, the color of a paper bag, hitched up his droopy jeans and exclaimed, “Two G’s, yo!” splaying two fingers like a sign of victory, the other hand in an arthritic semblance of a “G.” The replies were immediate and high-pitched. “Yeaah boyeee!” “What up, yo!” Then a trio found each other from the maze of Lynnea’s carefully organized seats and high-fived elaborately before leisurely sitting back down, happily grabbing their crotches.

Throughout the first day, she kept hearing this phrase; students in the hallway yelling, “2 G’s! 2 G’s!” She finally pulled two girls aside and asked what it meant. The girls looked at each other, tottering coltishly in their clunky Day-Glo shoes, all enlarged eyes and grins, muffling giggles on each other’s shoulders. Finally one girl composed herself enough to explain, “It mean two grand. Two thousand dollars. Like the Class of 2000. Get it?”

Lynnea nodded her head quickly, feigning remembrance of something she’d momentarily forgotten. She had wondered what the Class of 2000 would call themselves when she and people she called friends gathered in the Taco Bell parking lot to celebrate their own graduation. “What’re they gonna call themselves? The class of Double Nothing?”