Читать книгу About Grace - Anthony Doerr, Anthony Doerr - Страница 18

11

ОглавлениеDust shifting and floating above the bed, ten thousand infinitesimal threads, red and blue, like floating atoms. Brush it off your shelves, sweep it off your baseboards. Sandy dragged sheets of tin across the basement floor. Winkler cleaned the house, fought back disorder in all its forms, the untuned engine, the unraked lawn. All the chaos of the world hovering just outside their backyard fence, creeping through the knotholes; the Chagrin River flashing by back there, behind the trees. Wipe your feet, wash your clothes, pay your bills. Watch the sky; watch the news. Make your forecasts. His life might have continued like this.

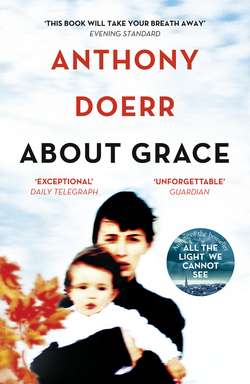

In October of 1976, Sandy was in the last, engorged weeks. Winkler coaxed her into walking with him through a park above the river. A generous wind showed itself in the trees. Leaves flew around them: orange, green, yellow, forty shades of red, the sun lighting the networks of veins in each one; they looked like small paper lanterns sailing on the breeze.

Sandy was asking about the anchor of the morning show who always had two cigarettes burning beneath the desk, and why she couldn’t see any smoke on TV. She walked with her hands propped beneath her distended abdomen. Winkler gazed up periodically at the twin rows of clouds, altocumulus undulatus, sliding slowly east. As they crested a hill, although this was a place he had never been, he began to recognize things in quick succession: the enameled mesh of a steel trash can, broken polygons of light drifting across the trunks, a man in a blue windbreaker climbing the path ahead of them. There was a smell like burning paper in the wind and the shadow of a bird shifted and wheeled a few yards in front of them, as—he realized—he knew it would.

“Sandy,” he said. He grabbed her hand. “That man. Watch that man.” He pointed toward the man in the wind breaker. The man walked with a bounce in his step. All around him leaves spiraled to earth.

“He wants to catch leaves. He’ll try to catch leaves.”

A moment later the man turned and jumped to seize a leaf, which sailed past his outstretched hand. Another fell, and another, and soon the man was grasping around him and stepping from the path with his hands out in front of him. He lunged for one and caught it and held it a moment in front of his eyes, a bright yellow maple leaf, big as a hand. He raised it as if hoisting a trophy for cheering onlookers, then turned and started up the hill again.

Sandy stood motionless and quiet. The wind threw her hair back and forth across her face. Her cheeks flushed.

“Who is he?”

“I don’t know. I saw him in a dream. Two nights ago, I think.”

“You saw him in a dream?” She turned to look at him and the skin across her throat tightened—she looked suddenly, he thought, like Herman, standing in the doorway to his house, looking him over.

“I didn’t even remember it until just now, when I saw him again.”

“What do you mean? Why do you say you saw him again?”

He blinked behind his eyeglasses. He took a breath. “Sometimes I dream things and then, later, they happen in real life. Like with you, in the grocery store.”

“Huh,” she said.

“I tried to tell you. Before.”

She shook her head. He exhaled. He thought he might say more, but something in her face had closed off, and the opportunity passed.

She went on, walking ahead of him now. Again she laced her hands at her belt, but this time it struck him as a protective gesture, a mother hemming in her cub. He reached for her elbow. “Take me home, please,” she said.

Dad will soak his new pipe in the sink; Mom will come home with a patient’s blood smeared across her uniform; the grocer will hand down two pretzel sticks from the jar on top of his counter and wink. A man, strolling through a park, will try to catch leaves.

Who would believe it? Who would want to think time was anything but unremitting progression, the infinite and indissoluble continuum, a first grader’s time line, one thing leading to the next to the next to the next? Winkler was afraid, yes, always afraid, terminally afraid, but it was also something in Sandy herself, an unwillingness to allow anything more to upset the realm of her understanding. Her life in Cleveland was tenuous enough. He never brought it up to her again except to ask: “You ever get déjà vu? Like something that happens has happened before, in your memory or in a dream?” “Not really,” she had said, and looked over his shoulder, toward the television.

But he’d dreamed her. He’d dreamed her sitting on top of him with her eyes closed and her hands thrown back and tears on her cheeks. He’d dreamed the revolving rack of magazines, the dusty light of the Snow Goose Market, the barely visible vibrations of her trillion cells. And hadn’t she dreamed him, too? Hadn’t she said as much?

It was a thorn, a fissure, a howitzer in the living room, something they taught themselves not to see, something it was easier to pretend did not exist. They did not speak on the drive home. Sandy hurried downstairs and soon afterward he could hear her torch fire up, the high, flickering hiss, and the smell of acetylene rose through the registers. From the kitchen window he watched leaves curl into fists and drop, the landscape revealing itself, deeper and deeper into the woods, all the way back to the river. He checked the barometer he’d nailed to the family room wall: the pressure was rising.