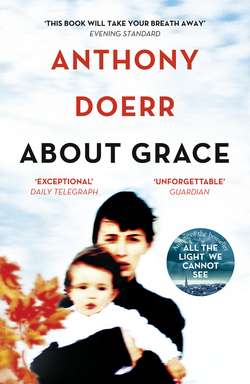

Читать книгу About Grace - Anthony Doerr, Anthony Doerr - Страница 25

2

ОглавлениеSt. Vincent’s hillsides were a foreboding emerald, patched with cloud shadow and the paler green of cane fields. From his window he could see a row of tin warehouses, an arrowroot-processing plant, a dirt field with netless soccer goals at either end. Knots of pastel-colored houses clung to the mountainsides. A syrupy, melancholy smell that Winkler associated with old meat permeated the air. Frigate birds hovered in drafts high over the port.

That first night he hiked a nine-hole golf course left to ruin behind the hotel, six-foot stalks of peculiar, spiky plants nodding in the fairways; ivy creeping over the tee boxes; a family of gypsies in semipermanent encampment on what had been the third green. Few lights burned except fires along the beaches, the mast lights of yachts, and a dozen or so flashlights conveyed by unseen commuters, shuttling between leaves like misplaced stars.

The palms stirred. Tiny sounds took on distorted importance: a pebble rattled under his shoe; something rustled in the scrub. Frogs shrieked from the branches. He wondered if he had not fled New York but the present as well.

A sign for a public telephone was bolted to the wall of the post office. He took up position with his back against the entry gate and fell in and out of nightmares. In the morning a woman dressed neck to ankle in denim nudged him awake with her toe. A crucifix swung from her neck: a cross as big as her hand with an emaciated Jesus welded to it.

“I need to make a phone call,” he said. “Can you speak English?”

She nodded slowly, as if considering her answer. Her cheekbones were high and severe; her hair was straight and black. Spanish, maybe? Argentinean?

“I have to call America.”

“This is America.”

“The United States.”

“Twenty E.C.”

“E.C. What’s E.C.?”

She laughed. “Money. Dollars.”

“Can I call collect?”

“Will they accept?” She laughed again, unlocked the gate, and ushered him inside the post office. He wrote the number on a slip of paper; she went behind the desk, spoke into the receiver a moment, and passed it to him. In the line he could hear miles of wires buzzing and snapping, a noise like a thousand switches being thrown. There was a sound like a bolt sliding home, then, miraculously, ringing.

It astonished him that a sequence of wires, or maybe satellite relays, might actually run from that island all the way to Shadow Hill, Ohio—how was that possible? But he was not so far away, not yet. He could imagine the phone on the kitchen wall with ruinous clarity: fingerprints on the receiver, the plastic catching a rhombus of light from the window, the bell’s mechanical jingle. What time would it be there? Would the ringing wake Grace? Would the house still be damp, would he have been fired, would an insurance check have arrived?

He was fairly certain he had been gone eighteen days. He imagined Sandy plodding to the phone in her pajamas. She was flipping on lights, clearing her throat, lifting the receiver from its cradle—she would speak to him now.

The line buzzed on and on: a simulation of ringing he wasn’t used to. His tongue was like a pouch of dust in his mouth. It rang thirty times, thirty-one, thirty-two. He wondered if the house was submerged underwater, at the bottom of some new lake, the phone still clinging dumbly to the wall, the cord brought horizontal and fluttering in the current, minnows nosing in and out of the cupboards.

“Not home,” the operator said. It was not a question. The post office woman looked at him expectantly.

“A few more rings.”

The wall of the post office was white and hot in the sun. The silos of a sugarcane mill, painfully bright, reared above the town. At a kiosk he bartered his suit jacket with a man whose patois was so thick and fast Winkler could not understand any of it. Winkler ended up with a salt cod, a pineapple, and two jam jars filled with what he thought might be Coca-Cola but turned out to be rum.

A pair of women strolling past, carrying baskets, nodded shyly at him. He followed them awhile, down an unpaved street, then turned and descended through thorny groves to a beach. Small green waves sighed in from the reef. He heard what he thought were occasional voices in the trees behind him but even in full sunlight it was dark back there and he could not be sure. From high on the hills came the bells of goats moving slowly about.

That sweet, carrion smell crept under the breeze. The cod was oily and stirred in his gut. He raised the first rum jar and stared at it a long time. Tiny gray clumps of sediment floated through the cylinder.

He had been drunk only once before, at a chemistry department party in college when, in a fit of introversion, he quarantined himself on top of a dryer in the hostess’s laundry room and gulped down four consecutive glasses of punch. The room had begun to spin, slowly and relentlessly, and he had let himself out through the garage and thrown up into a snowbank.

Dim clouds of mosquitoes floated at the edges of the trees. He sipped rum all that morning and afternoon and rose from the sand only to wade into the sea and relieve himself. By evening strange waking dreams possessed him: a dark-haired girl hauled a sack through woods; a row boat capsized beneath him; the woman from the post office prayed over a halved avocado, her crucifix swinging through the light. He dreamed freezing lakes and Grace’s little body trapped beneath ice and the heart of an animal hot and pumping in his fist. Finally he dreamed of blackness, a deep and suffocating absence of light, and pressure like deep water on his temples. He woke with sand on his lips and tongue. The sun was nearly over the shoulder of the island—the sky seemed identical to the previous morning’s. The same cane mill stood brilliant and white in the glare.

Another day. Beside him a tiny snail worked its way around the rim of an empty rum jar. His dream—the asphyxiating blackness—was slow in dwindling. Dark spots skidded across his field of vision. He rose and picked his way through the grove behind the beach.

In an alley behind a series of hovels he pulled lemons from a burl-ridden tree and ate them like apples. An old woman tottered out, shouting, shaking a mop at him. He went on.

In the days to come he telephoned the house on Shadow Hill Lane a dozen times—each time the call went unanswered; each time he begged the operator to wait a few more rings. He wondered again if the freighter had carried him to a new location in time, a future or past that did not coincide with Ohio’s. Here it was a day like any other: a hot, dazzling sky, blackbirds screeching at him from the trees, boats sliding lazily in and out of harbor. There what day was it? Maybe it was years later—maybe, somehow, it was still March, maybe he was still asleep in his bed, upstairs, beside Sandy, Grace sleeping her steadfast sleep down the hall, the first raindrops fattening in the clouds.

But it was April 1977. Back home the yard was coming to life, the flood receding into memory. Were they burying Grace? Maybe the funeral had already happened and now there were only memorial-fund canisters beside checkout registers, a grave, and leftover vigil programs neighbors had kept on their kitchen counters too long and now were guiltily folding into the trash. Grace Pauline Winkler: 1976–1977. We hardly knew you.

The American Express office could not reach his wife, they said, to see if she would wire money. A tall, purple-skinned man at the bank said he could not access Winkler’s checking or savings without a current passport. “Technically, sir,” he stage-whispered, winking, “I make a call and you get locked up at Immigration.”

He pawned his belt; he pawned the laces from his shoes. He ate stale croissants salvaged from bakery seconds, a dozen discarded oranges with white flesh. When he couldn’t bear his thirst he took sips from the second jar of rum: sweet, thick, painful.

In a moment of courage he asked the post office woman to dial Kay Bergesen, Channel 3’s “News at Noon” producer. Kay accepted the charges. “David? Are you there?”

“Kay, have you heard anything?”

“Hello? I can’t hear you, David.”

“Kay?”

“You sound like you’re in Africa or something. Look, you have to get in here. Cadwell is pissed. I think he might have fired you already—”

“Have you heard from Sandy?”

“—you just disappeared. We didn’t hear squat, what were we supposed to think? You have to call Cadwell right now, David—”

“Sandy,” Winkler said, wilting against the post office wall. “And Grace?”

Kay was shouting: “—I’m losing you, David. Call Cadwell! I can’t fend—”

Twenty-one days since leaving Ohio. Twenty-two days. He tried the neighbor, Tim Stevenson, but no one answered; he tried Kay again but the connection broke before it could be completed. The post office woman shrugged.

In the afternoons, storms came over the island and he sheltered on the fringe of his small beach under the low-slung palms. Every few hours more blood seemed to drain from his head, as if his heart was no longer up to the task of circulation, as if this place held him in the grips of a more powerful form of gravity. At night tiny jellyfish washed ashore and lay flexing in the sand like strange, translucent lungs. Sand fleas explored his legs. He took to sleeping in long stints and when he woke his same dream of blackness faded slowly as though reluctant to leave. Somewhere out past the reef lightning seethed and spat and he turned over and slept on.