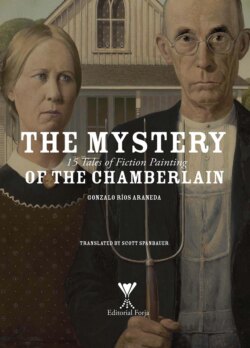

Читать книгу The Mystery of the Chamberlain - Gonzalo Ríos Araneda - Страница 6

THE VISITOR

ОглавлениеCave of Altamira

The Bison (detail), 14,800 to 14,400 B.C.

Skepticism had taken hold of men of good will, while a rebellious silence mingled with the Cantabrian winds that, at this hour, bussed the cliffs timidly. It seemed that time had stopped at their brink allowing any movement to expire. The Clan of clans had decreed that Inar should die at the priest’s hands for not knowing how to maintain intact a cave placed under his care.

The oral law, transmitted from fathers to sons, ordered that the Clan’s caverns could not be occupied as shelter once consecrated, which became a reality the moment any family project began to take form. The master had ignored the danger represented by the dwellingseekers, an organization of intermediaries who, protected by the tribal hierarchy, took control of any cave, cavern or den not seized by the tribe. They profited in this way at the expense of families that lacked housing and found themselves obliged to live with in-laws.

When he received that order from the Clan, Inar was just ending his stint with the paintings of the great Cavern, the sanctuary to which he had dedicated almost his whole life, and the reason he had entrusted Akar, his friend and second-in-charge, with nominating the men who would join them in the work. He couldn’t understand how those speculators had gotten the jump on him if only he and Akar knew about the cavern. With a deep sigh he thought there was nothing he could do but obey the ancient commandment and submit to the executioner.

Despite the fact that the sentence freed him immediately from his obligations as an artist, Inar set out to complete the final phase of his sacred work. There were so many times he had risked his health and forgotten about himself. Perhaps that persistent cough that afflicted him to the point of exhaustion was due to the rarified atmosphere resulting from the oil pyres lit in its interior. But he was ready to do his duty.

Twelve men carrying fired clay pots filled with a sticky substance presented themselves before the master who waited at the entrance to the cave. A fresh breeze blew through the forest and the hissing leaves of the giant birch trees shrouded the atmosphere in a strange unease. Had an unexpected circumstance not intervened as he entered the place, master Inar might have passed peacefully through the space that separated him from his own death; but the news delivered by the young apprentice Uzer filled him with bitterness. Quietly, and away from the others, Uzer informed him that Akar was colluding with the dwellingseekers; he had seen them forging agreements together. Inar remembered that the day before, in the foundation of damp earth located in the entrance to his residence, he had seen Akar’s symbol inscribed, which the night’s rain had taken pains to erase. Someone tried to alert him to it, but it wasn’t Uzer, because he said as much to Inar. He remembered being shaken by the betrayal. Looking around him he saw Uzer, but he didn’t find Akar among his men, at the same moment that he felt a worsening of that fear of heights that had unsettled him since he was a boy. In spite of that, he climbed to the top of the platform and remained at work for two long hours until, with his hands covered in ochre and the corners of his mouth dirty with plant soot, he completed the final retouching of the animal scenes that ensured the continuity of life.

He never told anyone that a spirit, perhaps an atavu, led him into the depths of the cavern and accompanied him while he directed his artists’ work in a fundamental spirit of freedom and exultation, whose source he was completely unaware of; he only understood that his abilities took on a rhythm and a linear direction that brought him and his men to an uncommon state that he didn’t hesitate to attribute to the sacred character of the cavern. Inar knew that he would take the secret of his angel, the atavu that probably accompanied his ancestors as well, to the grave. He saw himself simply as the inheritor of a timeless and increasingly valued tradition thanks to the able and intuitive actions of all those who assisted him to this day in drawing his objects of veneration.

He turned onto his belly and felt nauseated, something he’d been feeling increasingly over the last few hours. He thought of the executioner who awaited him at the cavern’s entrance and a shadow seemed to reach out to him in the shroud-like darkness. Like the dead weight of a rock hurled into space, his body went headlong over the handrails and the cord of woven fiber gave way instantly. Inar fell from the very top and ended up prone on the rough ground, which was only somewhat softened by the humidity. But he was conscious, because he saw that he was being carried to the entrance, and that they were laying him on a bed of leaves.

Later, a man placed a mud compress on his forehead as a melancholy chant droned in the distance. He stayed that way tucked into his silence until a rhythmic clapping of hands began to fill the place. More and more clapping, louder and more regular. It was the posthumous tribute his men were offering him, all of them committed as artists to the perpetuation of the human species, their deepest belief. Soon, a feeling of intangible withdrawal brought him to a state of basic emptiness, which, like a spontaneous sort of regeneration, began to be filled with pulses and vibrations that were no longer his own; until a growing murmur took over the surrounding area. The renowned expert Joseph Werner Rospigliossi took a few steps forward and bowed in thanks to the city of Paris. He was in the very center of Western culture receiving a crowd’s applause. Standing in front of the dais the municipal government had installed in one of the historic building’s galleries, he was receiving an award for his work as a docent and art authority after staging the largest exposition of figurative skill ever seen, in direct comparison with cave art.

Truly, there had never before been a cultural statement like it, other than in the minds of a few theoreticians and researchers interested in solving the mystery of a few Magdalenian paleolithic capabilities that modern art had taken two thousand years to achieve. And one of those men was Werner Rospigliossi himself, charged with presenting, in the building’s spacious galleries, the most significant exponents of design and expression in modern times, along with their debt to Altamira and Lescaux. Its success provoked the interest of experts who, gathered in the City of Light, were able to admire in their representation their purity of movement and the expressive relevance of their flourishes. Such were the commentaries that filled the critics’ columns the day after the event opened. Among those chosen by Werner were the names Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec and Renoir, of whom someone said that the imprint of their movements was mysteriously tied to the expressive touch of the Cantabrian paintings of fourteen thousand years ago.

Undoubtedly, the expert was the man of the moment. He had also allowed himself time to deliver a chat about the enigma of figurative skills in stone and their impact on the development of modern art in the archaic aura of many of those skills’ creations.

In the hotel where he was staying, Professor Werner, who was traveling unaccompanied in Europe at the time, received a telegram from his wife telling him how proud she was of him. “My indispensable artist, I love you desperately,” she had written in the last line; and in an aside she advised him not to forget his bronchial pills. “I await you longingly.”

That Friday the professor left the hotel in the direction of Orly airport as night began to fall. There, standing in the west terminal, boarding procedures completed and having bidden the authorities farewell, he thought of his wife, his asthma, and his fear of airplanes. Then, resolute, he moved ahead in search of his first-class seat.

Without a second thought, and before buckling his seatbelt, he took a pill from his shirt pocket, one that he later dissolved under his tongue as the huge machine lifted off in search of the Atlantic. He flipped through a revue, and in no time fell deeply asleep. He didn’t notice when a man collected the magazine that had fallen between his legs and placed it back in his lap; nor that he had kindly turned off his seat’s individual reading lamp. The roar of the mechanical beast’s motors had just taken on an irregular feel. Minutes later a deafening explosion enveloped the craft in a ball of fire, rapidly devoured by the ocean.

After the plane disappeared completely beneath the waves, more than twenty years would pass before a team of experienced divers would find it on the bottom of the sea. It lay sunken just off the coast of Cantabria on the Iberian Peninsula.