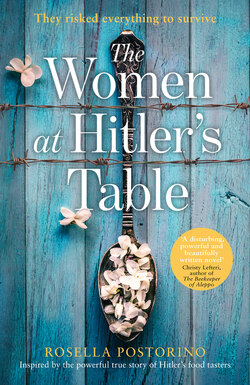

Читать книгу The Women at Hitler’s Table - Rosella Postorino - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеWe had never been Nazis. as a little girl i hadn’t wanted to join the Bund Deutscher Mädel, hadn’t liked the black neckerchief that hung down the front of their white shirts. I had never been a good German.

But that day, surrounded by the white walls of the lunchroom, I became one of Hitler’s food tasters. It was autumn 1943. I was twenty-five and had fifty hours and seven hundred kilometers of travel weighing on me. To escape the war, a week earlier I had moved from Berlin to East Prussia. I had come to Gross-Partsch, the town where Gregor had been born, though Gregor wasn’t here.

They had shown up unexpectedly at the home of my parents-in-law the day before that first meal. We’re looking for Rosa Sauer, they said. I didn’t hear them because I was in the backyard. I hadn’t even heard the sound of the jeep coming to a halt out front but had seen the hens scurrying toward the henhouse all at once.

“They’re asking for you,” Herta said.

“Who is?”

She turned away without replying. I called out for Zart the cat, but he didn’t come. In the morning he would go off to wander around town. He was a worldly cat. I followed Herta, thinking, Who could be looking for me, no one knows me here, I’ve only just arrived, oh, god, has Gregor come home?

“Has my husband returned?” I asked breathlessly, but Herta was already in the kitchen, her back turned to the door, blocking the light. Joseph was also on his feet, stooping with one hand resting on the table.

“Heil Hitler!” Two dark silhouettes thrust their right arms in my direction.

I raised my arm in reply as I stepped inside. In the kitchen were two men in gray-green uniforms, pale shadows shrouding their faces. One of them said, “Rosa Sauer.”

I nodded.

“The Führer needs you.”

He had never seen my face, the Führer. Yet he needed me.

Herta wiped her hands on her apron as the SS officer continued to speak, addressing me, looking only at me, scrutinizing me as if to make an appraisal: a sturdy piece of craftsmanship. Of course, hunger had somewhat debilitated me, the air-raid sirens at night had deprived me of sleep, and the loss of everything, of everyone, had left me weary-eyed, but my face was round, my hair full and blond … Yes, one look says it all: a young Aryan female tamed by war, a one hundred percent genuine national product, a fine acquisition.

The officer walked to the front door.

“May we offer you something?” Herta asked, too late. Country folk didn’t know how to receive important guests. Joseph stood up straight.

“We’ll return tomorrow morning at eight. Be ready to leave,” said the other SS officer, who until then had remained silent. Then he too walked to the front door.

The Schutzstaffel were declining out of politeness, either that or they weren’t fond of roasted acorn coffee, though perhaps there was some wine, a bottle saved in the cellar for when Gregor returned. Or they were practicing self-restraint, hardening themselves through abstention, force of will. Whatever the case, they didn’t even consider Herta’s offer, admittedly tardy.

They shouted, Heil Hitler! raising their arms—toward me.

Once they had driven off, I went to the window. The tire tracks in the gravel marked the path to my death sentence. I shot to another window in another room, ricocheting from one side of the house to the other in search of air, in search of a way out. Herta and Joseph followed me. Please, let me think. Let me breathe.

IT WAS THE mayor who had given them my name, according to the SS. The mayor of a small country town knew everyone, even newcomers.

“We’ll find a way out.” Joseph tugged his beard in his fist as though a solution might slip out. Working for Hitler, sacrificing one’s life for him—wasn’t that what all Germans were doing? But that I might ingest poisoned food and die, not from a rifle shot, not from an explosion, Joseph couldn’t accept it. A life ending with a whimper, perishing out of view. Not a hero’s death but a mouse’s. Women didn’t die as heroes.

“I have to leave.” I rested my cheek against the window. Each time I tried to take a deep breath, a stabbing pain by my collarbone cut it short. I changed windows. A stabbing pain by my ribs. My breath couldn’t break free. “I came here to live a better life …” I laughed bitterly, a reproach to my parents-in-law, as though they had been the ones to offer my name to the SS.

“You must hide,” Joseph said, “seek refuge somewhere.”

“In the woods,” Herta suggested.

“In the woods where? To die from cold and hunger?”

“We’ll bring you food.”

“Naturally,” Joseph confirmed. “We would never abandon you.”

“What if they come searching for me?”

Herta looked at her husband. “Do you think they would?”

“They won’t be pleased, that’s certain.” Joseph wasn’t getting his hopes up.

I was a deserter without an army, ridiculous.

“You could go back to Berlin,” he said.

“Yes, you could go back home,” Herta echoed. “They won’t follow you all the way there.”

“I don’t have a home in Berlin anymore, remember? If I hadn’t been forced to, I never would’ve come here in the first place!”

Herta’s features tensed. I had shattered the politeness that had stood between us because of our roles, because of our scarce familiarity with each other.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to—”

“Never mind,” she said stiffly.

I had been disrespectful to her, but at the same time I had thrown open the door to intimacy between us. She felt so close that I longed to cling to her. Keep me with you, take care of me.

“What about you two?” I asked. “If they come and don’t find me here, they might take it out on you.”

“We’ll manage,” said Herta. With this, she turned and left.

Joseph let go of his beard. There was no solution to be found there. “What do you want to do?”

I would rather die in a foreign town than in my own city, where I no longer had anyone.

ON MY SECOND day as a food taster I rose at dawn. The cock was crowing and the frogs had suddenly stopped croaking, as though falling into an exhausted sleep all at once. It was then that I felt alone, after an entire night awake. In my reflection in the window I saw the circles around my eyes and recognized myself. They hadn’t been caused by insomnia or the war. Those dark furrows had always been there on my face. Shut those books, look at that face of yours, my mother would say, and my father would ask, Do you think she has an iron deficiency, Doctor? and my brother would rub his forehead against mine because the silky caress would help him fall asleep. In my reflection in the window I saw the same circled eyes that I’d had as a girl and realized they had been an omen.

I went out to look for Zart and found him curled up, snoozing beside the henhouse as though looking after the hens. It wasn’t wise to leave the ladies unattended—Zart was an old-fashioned male, so he knew that. Gregor, on the other hand, had gone away. He had wanted to be a good German, not a good husband.

The first time we had gone out together he’d asked me to meet him at a café near the cathedral, and he arrived late. We sat at a table outside, the air chilly despite the sunshine. Enchanted, I heard a musical motif in the chorus of birds, saw in their flight a dance performed just for me, for this moment with him had finally arrived and resembled love as I’d imagined it ever since I was a little girl. A bird broke away from the flock. Proud and solitary, it plunged down almost as if to dive into the Spree, brushed the water with outstretched wings, and instantly soared up again. It had followed a sudden urge to escape, a reckless act, an impulse driven by euphoria. That same feeling tingled in my calves. Facing my boss, the young engineer sitting before me at the café, I found I was euphoric. Happiness had just begun.

I had ordered a slice of apple pie but hadn’t tasted it yet. Gregor pointed this out. Don’t you like it? he asked. I don’t know, I said, laughing. I pushed the plate forward, offering it to him, and when I saw him put the first piece into his mouth and chew quickly, with his customary enthusiasm, I wanted to as well. And so I took a bite, and then another, and we found ourselves eating from the same plate, chattering about nothing in particular without looking at each other, as though that were already too intimate, until our forks suddenly touched. When they did we fell silent, looking up. We stared at each other for a long while, as the birds continued to circle overhead or came to rest on branches, on balustrades, lampposts, who knew, perhaps they were diving down to plunge beak-first into the river, never again to emerge. Then Gregor pinned my fork down with his, and it was as if he were touching me.

HERTA CAME OUTSIDE to collect the eggs later than usual. Perhaps she too had spent a sleepless night and was having a hard time waking up that morning. She found me there, sitting on the rusty metal chair, Zart curled up on top of my feet. She sat down beside me, forgetting about breakfast. The door creaked.

“What, are they here already?” Herta asked.

Leaning against the doorframe, Joseph shook his head. “Eggs,” he replied, gesturing at the henhouse. Zart scampered after him, and I missed his warmth.

The soft glow of sunrise had withdrawn like the tide, laying the morning sky bare, pale, drained. The hens began to squawk, the birds to twitter, the bees to buzz against that circle of light overhead, but the squeal of a vehicle coming to a halt silenced them.

“Get up, Rosa Sauer!” we heard them shout.

Herta and I leapt to our feet and Joseph returned carrying the eggs. He didn’t notice he’d clutched one of them too tightly and had broken its shell, the yolk oozing through his fingers in viscous rivulets of bright orange. I stared at them. They were about to drip from his skin and would hit the ground without making a sound.

“Hurry up, Rosa Sauer!” the SS officers insisted.

Herta touched my back and I moved.

I chose to await Gregor’s return. To believe the war would end. I chose to eat.

IN THE BUS, I glanced around and sat in the first empty spot, far from the other women. There were four of them, two sitting next to each other, the others sitting on their own. I couldn’t remember their names. I only knew Leni’s, and she hadn’t been picked up yet.

No one replied when I said good morning. I looked at Herta and Joseph through the window, which was streaked with dried rain. Standing by the doorway, she raised her arm despite her arthritis, he still held a broken egg in his hand. I watched the house as it fell behind—its moss-darkened shingles, the pink paint, the valerian blossoms that grew in clusters from the bare earth—until it disappeared behind the bend. I would watch it every morning as though I were never to see it again. Until one day I no longer felt that longing.

THE HEADQUARTERS WERE three kilometers from Gross-Partsch, hidden in the forest, invisible from the air. When the workers began to build it, Joseph told me, the locals wondered why there was all that coming and going of vans and trucks. The Soviet military airplanes had never detected it. But we knew Hitler was there, that he slept not far away, and perhaps in summer he would toss and turn in his bed, slapping at the mosquitoes that disturbed his slumber. Perhaps he too would rub the red bites, overcome by the conflicting desires caused by the itch: though you couldn’t stand the archipelago of bumps on your skin, part of you didn’t want them to heal because the relief of scratching them was so intense.

They called it the Wolfsschanze, the Wolf’s Lair. “Wolf” was his nickname. As hapless as Little Red Riding Hood, I had ended up in his belly. A legion of hunters was out looking for him, and to get him in their grips they would gladly slay me as well.