Читать книгу Seize the Day - A M (Jack) Harris - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preamble

ОглавлениеTo some readers I hope that it does not appear that I have an enduring preoccupation with myself because in the words to follow I am only trying to review my life in full. To begin, I sailed to Australia’s war in Korea from Japan in mid-1950 and, thinking now about that service, I find that many recollections, some buried deep in my memory bank, have flooded back with the utmost clarity, the more so after chatting with old comrades. Afterwards, though, I am sometimes haunted with remorse about what I should have done, but really could not. War is unreasonable, even though in my time getting over the wire in the approved British tradition was applauded, comradeship was honoured, we thought we knew why were fighting in Korea, and that our military success was laudable.

By the time of the Apple Orchard Battle of 22 October 1950, I had come to understand that in battle the infantry soldier has very little knowledge or understanding about what is happening beyond the ten men in his section. Those men are of prime concern and so it was that the men I walked with at the opening of the Orchard Battle had no fear of being shot or wounded, but there was apprehension about what was ahead of us, who might be waiting at the top of the hill, and in the unknown. My first ordered objective was the clearing of mines or men from a culvert to our front so as to allow the Sherman tanks to proceed with safety. Getting there, in a heart-breaking moment the young soldier with me nervously fired his rifle, almost shot me in the head, and badly wounded another soldier who had stepped down to examine the culvert on the far side. It was a mess to begin with, but at the end of the battle some three hours later we had come through, and had grown in stature. We had been to the crest, we had looked down, our enemy were in mass flight and the young soldiers, including myself, were now seasoned warriors.

On 30 October 1950 I was wounded at Chongju, a town not far from the Yalu River and the Chinese border. My commanding officer was killed the same day. I was returned to Australia for medical treatment, then attended a one-year course in Chinese; some time later I was back in Korea in charge of what was called a Special Agent detachment. On 2 July 1953 I swam across the flooded Samichon River with three South Korean agents. On the far bank of the river I divided my party into two groups. Then with an agent named Pak I proceeded along the river but we were ambushed and Pak was killed. I can still see six red dots, the bullets from a machine gun, hitting Pak and killing him instantly and I am often concerned that I never managed to get hold of Pak’s body, get him into the Samichon, and have him carried down to our own lines. It would have been impossible of course, but one can dream things incompatible with fact.

I should here note that the routes we explored when moving through North Korea, and places like Kunwari and Namsong-Dong are fictitious. As I have cautioned in an earlier work, the so-called ‘dark forces’ are still in control in that part of Korea today, so many years after the conclusion of the war there and any person, or relatives of that person, who may have assisted the allies during that war would still be subject to retribution.

Additional to this, many of the names I mentioned when writing about Buronga have been altered from the original to avoid and hurt, or discomfort. Buronga I have also discovered, is a lovely place with a happy community, not a sandy patch of hill covered with bag shanties all served with the one corrugated track of my childhood memories.

I conclude here by stating that I spent eight of the best years of my life in the army. What followed after my discharge was fashioned by that experience, and the friendships I knew as a soldier. For all that I am eternally grateful.

A. M. (Jack) Harris.

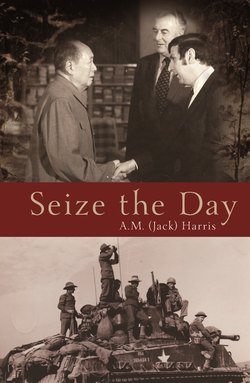

The author at age 20, when he joined the army at Mildura in May 1946