Читать книгу Seize the Day - A M (Jack) Harris - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеAt first light we moved carefully in past the standing patrol of the forward company as the poor visibility of the valley was improving. I called a greeting to a number of shivering British soldiers and they spread their arms wide, welcoming us in return. After all, they had spent long hours peering into the darkness which often seemed hostile to them as they listened for any sound that might indicate the approach of their enemy, anxious to take a prisoner, or perhaps to explore the defences of the outer perimeter in preparation for an attack. All night through they had gripped their weapons and waited, hoping that any enemy would not choose to come at them, firing in the dark. They had waited, thinking of home, of love, of the need for a smoke, and perhaps, sometimes, of death. They would always be ready for the first warning when they would shoot and, in a weaving, terrified run, get back through the minefield to warn their comrades and, primarily, preserve their own lives.

But the enemy had not violated their night, and now in the welcome light of dawn they stood and sat, sucking hungrily on their cigarettes, chaffing one another as Lim and I walked up to them. They laughed at themselves and at the two mud-spattered men, me and Lim, in a strange happiness that another fresh day was dawning. In the satisfaction which refused to acknowledge a fear of another night, they would not now consider the crawling dread of the next outpost position, which would begin again in a few short hours.

The corporal in charge spoke to us in a laconic fashion, as some men do when they joke about serious matters.

“Had a good time, Sergeant? Looks like it!”

I did not immediately answer but grinned in companionship.

“Wonderful. The water was great. Those buggers worry you at all last night?”

“Nuh. Haven’t been in touch with him for about three weeks now. Bloody good thing too! Came right up to this spot!” He pointed a little way into the valley. “Killed two of our blokes; snatched another, they did! Cunning bastards!”

“True.”

“But I’m thinking he’ll be coming again soon.” The comment came from one of the soldiers sitting on the ground near the corporal. He spoke in a thick Scottish burr and winked broadly at me as he spoke.

“You know exactly when that will be, Scotty?” I asked.

“When he hears that me, James McFee, is going on leave to Tokyo, and will not be mounting patrol for three weeks,” The Scot spoke complacently, ignoring the storm of derision his words had unleashed.

“Huh! Would you get that?” The corporal spread his hands upwards in mock resignation. “No self-respecting Chink would ever try to take you prisoner, McFee, you Scotch rooster. You would not be worth the trouble: besides, they got no Scotch-Chinese interpreters.”

“You may have a point there,” I commented with a grin. I did it in the hope of prolonging this moment of warmth and comradeship and humour, to let the bawdy familiarity of soldier-talk smooth away the remembered anxieties of the night just passed. “Who interprets for you in Tokyo, Scotty?”

“Say no more!” the Scot remarked, his burr thicker than ever. “Y’re all jealous that I’m goin’ to Tokyo with ten pounds sterling in me pocket!”

“Ten pounds!” one of the soldiers ejaculated. “Christ, that wouldn’t even get you an old bag outside the gates at Ebisu!”

“I’m not intending to pay for anything but me beer,” the Scot remarked witheringly. “You must understand that creatures of fleshly delights fall easily to the charms of McFee!”

“For Christsakes!” the corporal swore. “Jock, you’d be the biggest bullduster ever!”

“Not me,” McFee responded darkly. “And I can assure you it will not be dust that I’ll be wasting on some of the superior Geisha gurrls I know in Tokyo!”

I joined in the laughter which followed McFee’s reply, and as I looked about at the laughing men surrounding me, I wondered for a moment at the duplication of this same sort of scene in many defensive positions set all along the parallel in this bright dawn; of all the other soldiers, secretly fearing, as these men did, what another night might bring, but finding relief from their concern in merriment. Almost as my mind conceived the image of our allied armies dug in all along the 38th Parallel the Australians and the Canadians and Turks, the Americans and all the others nations involved it was replaced by the thought of the Chinese and the North Koreans facing them across the small waist of Korea. A lot of men were bogged down in this war and all, I knew, had only one wish and that was to see tomorrow. I knew that the Chinese and North Koreans would be standing-to now, in their defensive positions and I could not but wonder if they too were laughing and joking about the same things as their enemies: about women and home and love, about killing and getting killed, even though in the bright sunshine of the new day, that seemed improbable. But I was recalled to the present moment by the voice of the corporal.

“What was that?” I asked him.

“I said,” the corporal repeated. “Our commanding officer has organised a cup of coffee for you at the O-pip, if you felt like it. Knowing our CO I think you’d better feel like it. Okay?”

“Good! That sounds wonderful.” Turning to Lim who had been following the quick, slangy conversation with a half-comprehending grin, I added to it by saying, “Come on, Lim, let’s blow.”

As we walked away I called over my shoulder to McFee. “Have a good time in Tokyo, Scotty! Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do!”

“I might be doin’ a few things you couldn’t do, Sergeant!” Mcfee promised bleakly and he was swamped again by the ready derision of his companions.

Lim and I stepped warily through the marked gap of the minefield, then around a slippery curved path which led to a sand-bagged forward observation post. One of the sock-hatted soldiers watching us from there ducked his head down into the post and yelled for his platoon commander. A young-looking lieutenant pushed his head out of the door of the bunker and stared at us.

“I have orders from above to prepare a hot coffee for you. With something strong in it. I presume you are interested?”

“Presumption correct. Got enough for two of us, twice?”

“Sure. Come’n get it.”

Lim and I went quickly down a communication trench, ducked our heads and entered a big, rough-hewn bunker. The smell of earth and dampness pervaded the place but I knew that this bunker, like the hundreds scattered over the hills, was home for a soldier. A poor place and a transitory one where comforts were few and which a shell could turn into a shambles.

The young officer groped about into an empty old shell case and brought out three battered enamel mugs marked and chipped by the rough use of many hands. He slipped his fingers through the handles and with a dextrous movement placed them bottom down on four large shell cases which was the dugout table. He looked up at me and smiled. “The rum’s over there,” he pointed. “Help yourself.”

I reached behind me and into a suppurating cleft cut in the wall. The rum bottle I found was muddy but I handled it with due deference, placing it carefully on the improvised table, and soon the comforting aroma of hot coffee and rum blossomed on the damp air of the dugout. Lim stood back from the table, sipping at his drink with a gusty appreciation while the lieutenant and I discussed our patrol.

“It must have gone well,” he remarked. “But you sure are a mess! Can I get you some dry gear?”

“No. I’m roger. I was a bit damp before but I’ve dried out well. Except for my feet which are still damp but I’ll soon be home. I know I look somewhat dishevelled, as they say, but I’ll get my gear cleaned up.”

“Yes. I suppose so. I was told you wear a Chinese uniform but I found it hard to believe, until now when I see what you’re wearing. But if you were ever captured, wouldn’t you be executed?”

“No doubt. But I travel in enemy country and I have no option but to try and hoodwink the people back there, where I move about.”

“A silly question I suppose, but are you ever scared? I know I’d be petrified. I’m National Service, you see.” He sounded apologetic about it.

“I went for the heavy-duty rosary beads out there tonight myself,” I remarked. “All over a bloody pheasant!”

“A pheasant? How come?”

“We were crawling across a paddy field and the blasted thing shot up like a singed bat out of hell right under my hand. You know how the wings whirr? I thought it was a landmine or some such. I reckoned I was going to give birth!”

I laughed at my own story but inwardly marvelled that I could feel so happy, so buoyant as I always did, after a successful start to one of our missions. I would feel good for several days to follow and then the old gnawing fear would start again. What time, next time, what bloody time, would it not be simply a bird but a real bomb, or an enemy patrol which would give me a gut full of lead for my stupidity? Bugger it all! My thoughts were dispersed as the young officer coughed, and looked at me inquiringly after having said something.

I had missed a question once more. “Sorry. What was that?”

“I said that I’ve heard you have been out for several days yourself. Just you and these Korean chaps you control?” He nodded towards Lim. “It must be lonely work nerve-wracking as well.”

“I have excellent men.” I nodded directly at Lim, and continued. “But we are small fish and it’s a mighty big ocean out there, with too much water to net. Practically and looking at a map I suppose it does seem hopeless, but the odds are all with a small party pushing through the enemy lines. Which completes my sermon for today. We must be on our way. Thanks for the coffee and that additive.”

We laughed and I made a request. “I know you’ll be very careful for a few days, sir. Those two men who went out tonight will be back in ten days. You’ll watch out for them?”

“Of course. They’re in good hands.”

“I know. I just wanted to thank you.”

We left the dugout to make our way along a trench which sloped up until in a thin tear it wound its way through the earth and emerged on the reverse side of the hill. Dug in farther down that same slope was a company command post. I asked Lim to wait outside while I entered and reported briefly, and as a courtesy to the major in command, that my mission was well on the way, we had crossed the river and that I appreciated his help. I came out, signalled to Lim and together we hurried up to our camouflaged jeep and drove off into the early morning sunshine which was lending a sort of enchantment to the harsh contours of the hills. The day was softened but the impact of war was indelibly imprinted on the land for the enemy occupied positions about five thousand yards to the north, and as many of our lines were well within range of their big mortars. The road on which we travelled had high nets erected as protection, for if small puffs of dust raised by passing vehicles became discernible to the enemy’s forward observers, the area quickly became a target for a deadly rain of mortar fragments.

But now all was quiet. Tanks, mortars, machine-guns, cannon and soldiers, all were still. Many of the men who had survived the night had probably not yet taken hold of this new day in which they would fight, cut, destroy and be destroyed. But the business of war was, for the moment, at a standstill.

Our jeep was stopped at the bridge spanning the deep, fast-flowing Imjin River where our identity passes were checked. The drive continued until I swerved the vehicle off the main highway and onto a small track. Along this rutted lane way I was halted at a barrier by Korean youngster dressed in the uniform of South Korea’s National Police. He saluted smartly when he saw I was driving, then, with a big grin, he pressed on the weighted end of the barrier, raising it. I moved the jeep onto the top of a rise and drew it to a sliding halt in front of a group of old Korean homes, formerly a farming homestead. Doors and windows all about swung outwards and soon the courtyard was filled with a mob of yelling Koreans; this was the headquarters of my agent detachment, with its recruits and trained agents, some awaiting missions, some undergoing instruction.

I knew them all. Getting out from the jeep I spoke to some, talked with others, shook hands with two who had just returned from instruction in Seoul. Before going into my hut I sat on the front step, lit a cigarette and let my thoughts go in shadow and sunlight with the smoke, while allowing my eyes to follow the contours of the land about my place. It was a hard country creeping inward to envelop the paddy fields once won by the toil of the uprooted Korean farmers who had been forced by war to quit their villages. The fields tumbled down in an abandoned fashion from the hills, and with them, water which had been channelled to grow wheat and rice was spilling aimlessly over a narrow channel.

At the bottom of one of the abandoned paddy fields one of the agents, doubtless to pass the time away and probably to recall a life from which he had been rudely divorced by the coming of war, had erected a miniature water wheel. The water fell gently on to it and turned a spindle to which the builder had attached two small hammers. Under the impulse of the water the spindle clicked around to move the hammers and they rose and fell, beating with an easy rhythm as they did so on two tiny brass bells. The ring of the bells was crystal clear and peaceful, filling the valley with quiet, and beauty and peace.

But I knew that there was no quiet, no beauty and certainly no peace or comfort for Pak and Chet over the Northern mountains to my front where lay a thin haze. How were they doing? I wondered. They were somewhere behind that haze, while I lay in peaceful security, smoking. But why not? I asked myself. This whole stupid bloody business, this war, was drawing to a close. Both sides were sick of this conflict. I had been in it from the beginning in 1950, and I would like to get out of it, all in one piece, damaged though I was, by my first wounding. But right now, another mission was under way and this was the worst time for me, the waiting. I would wonder perhaps if the men on this or any other mission would be able to penetrate all the way through the enemy lines undetected. But if caught and questioned would they reveal this place, my headquarters, and also tell of the route we were using to get to our safe houses? Were some of my agents working for the enemy and taking to them valuable front-line information about the forward elements they were passing through? I could never be completely sure, even though I could communicate with them in Japanese, something their conquerors had imposed during their fifty-odd years of Korean occupation. Because I could never be completely sure of all of them and could only fully trust Lim and Pak, I only went out with those two men on top assignments. It was a tough job, rugged and demanding of the body, cruel and exacting on the nerves. I accepted that the reward for some was revenge, and that those who hated most bitterly might be most fully trusted. The reward for others was the fulfilment of an ideal, but that in extreme danger or capture the coward mind might elect to live against the dictates of an idealistic heart.

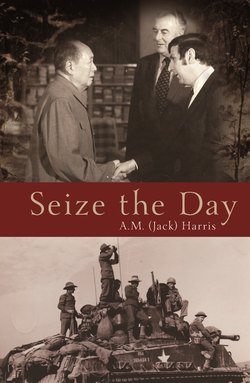

Pak and Chet in their village headquarters near the Imjin River

I believed I knew them all, the hater, the patriot, the idealist, and the mercenary, the lover of money; and most of all, I knew that the mercenary must be treated with the utmost caution, since if a man can gain from both sides, he is doubly happy. I knew them all, as well as a man might ever get to know another; in darkness and in light, in danger and in safety, with blood on their hands and hate in their hearts, but I could only trust two of them fully. And because my body was flesh, and my mind was tired with yearning, I knew I might not even fully trust myself. It was the price I paid for dealing in deceit.

*

Sitting there, thinking about my present life and the circumstances which had placed me in this spot, I involuntarily flexed my left hand which had been badly shattered and was bereft of all the knuckle bones, the metacarpus, was still in place but it had led to my medical re-classification out of infantry service. Of course there are battle risks for an infantryman, and I remembered how my commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Green had come to me when I was stretched out, badly wounded, and he had placed his hand on my shoulder, to say he was sorry to be losing me. He had returned to his part in the battle and later that day, he was mortally wounded. But here I was now, an intelligence operator, often sent to cross a dangerous river and patrol the land far beyond in more danger than any I had encountered as a fighting soldier.