Читать книгу Manikato - Adam Crettenden - Страница 5

Оглавление1

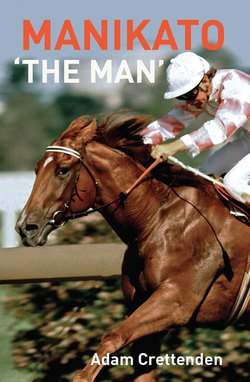

A Gifted Runner

The float was slowly steered up the driveway to the usual unloading spot. To avoid the oppressive February heat, the ten-hour drive from Adelaide to Melbourne started in the middle of the night and ended mid-morning at stables near Epsom Training Track in the suburb of Mordialloc. The cargo contained a $3500 equine yearling—a middle-of-the-road purchase price for a young horse in 1977.

At around 3pm the previous day, the colt had been presented at a small parade ring at the Wayville Showgrounds in Adelaide—lot 387. The sales complex was a scene of disrepair, with rotting timber in the horse stabling area and a ring made almost entirely of concrete. The hour of the colt’s sale was the hottest of the day. Under the shade of a tree it was 40°C, and inside the concrete structure it was considerably warmer.

There were scattered onlookers and countless flies as, one by one, yearlings were sold off at auction. The Coles Bros firm had put together a two-day sale for South Australian breeders to sell their young horses, and with three-quarters of the lots presented, crowd numbers were dwindling.

Lot 387 was led in and walked in tight circles in the confined ring. Those who hadn’t noticed him during the inspection phase raised their eyebrows. His body size was much larger than average, his head even more so. The back end of his body was already thick and rippling with muscle. He was far from the fragile adolescence of most of his peers—this horse had developed earlier than others his age.

The colt’s older half-sister, Tumerah, had been purchased the previous year from the same sale by agent, Ed McKeon, on behalf of Melbourne trainer, Bon Hoysted. Those familiar with this filly had an insight into the family bloodlines. Tumerah had proven troublesome to handle—unpredictable and unruly—but beneath those traits was plenty of talent, especially speed. Hoysted on-sold the filly to one of his stable clients and, despite her friskiness, she managed to win a race as a two-year-old over 1000 metres at a country track, and also placed in Melbourne.

Tumerah had gained Hoysted’s attention, and he was interested in any of her relations that came up for sale at auction. Once he noticed the pedigree of lot 387, he again called upon McKeon to attend and bid on his behalf. Hoysted secured the colt for a price comparable to that of Tumerah from the previous year.

This particular colt was sired by Manihi—a precociously fast sprinter who took out the 1967 Newmarket Handicap—and had been raised till this moment at the suburban Adelaide property of Ross Truscott. He owned the youngster, who was much larger in size than Tumerah, as well as the mother of the foal, Markato.

Truscott was a menswear store owner by profession, but dabbled in horse breeding over the years, always selling the resultant progeny. This colt was no exception; he was delighted to receive the $3500 as he departed from the Wayville Showgrounds on selling day with an empty horse float. He couldn’t have predicted how much the horse would actually be worth.

* * *

At the entrance to Bon Hoysted’s stable, the tailgate was lowered from the float. As the colt back-pedalled onto the ground and shifted his head to take in the scenery, Hoysted sized up his new charge. He screwed up his face.

His body was large, with a 78-inch girth nearing record width, and hindquarters that looked powerful. But it was his head that demanded attention—it was disproportionately larger again. He was far from a well-rounded specimen. It was as though some parts of his anatomy were developing faster than others.

Brooms stopped sweeping and manure rakes were set aside as the yearling colt was introduced to a vacant stable, along with the stablehands in attendance—their eyes wide open. Once the stable door was bolted, the staff’s usual duties resumed. Hoysted wiped sweat from his brow and walked inside the house to start planning the weeks ahead with his new youngster.

* * *

Norman Dedrick Hoysted was born on 23 December 1919 and dubbed ‘Bon’ as a young boy for his bonny and sociable nature. He was born with what is now known as Klippel-Feil Syndrome (KFS), a genetic defect in the development of the spine, which was scientifically identified the same year as Bon’s birth. In most cases, KFS causes a significant shortness of the neck.

Bon’s mother, Ellen, died when he was just eleven and her death hit Bon hard. She had protected Bon from ridicule surrounding his condition in his early years. He sought comfort from horses, immersing himself amongst the stables of his father, Fred.

It was no surprise that Bon became a horse trainer. Fred Hoysted, known as ‘Father Fred’, had been Melbourne’s leading trainer on seventeen occasions through the 1930s, 40s and early 50s. Hanging around his father’s Mentone stables, young Bon soaked up all the knowledge required to one day become a trainer himself. While Bon’s brothers, Wylie, Bill, Henry and Bob, had shown some interest in horses, Bon was the keenest.

By his early twenties Bon was stable foreman. His responsibilities surged during World War II when most of his brothers were called up for national service. Bon was not eligible to serve because of his disability, and by the time the war was over he’d gained a trainer’s license of his own.

When Fred retired in 1966 with ill health, Bon had established himself at nearby Epsom Training Track in the beachside suburb of Mordialloc. The finishing touches were being applied to a new brick veneer residence, which was built alongside the same stables at 4 Edith Street that had once been used by thirteen-time leading Victorian trainer, Jack Holt. Bon lived there with his wife, May, and daughters, Margaret and Patricia. A new row of boxes was constructed perpendicular to the existing ones. While Bon didn’t have a lot of feature-race winners, there were many ‘handy’ horses that kept the prize money cheques arriving.

Horses were everything for this middle-class family. They mixed with people of similar vocation and the major social event of the week was the Saturday outing to the Melbourne races. Both daughters met their husbands through racing circles; Margaret tied the knot with horse-breaker and budding trainer, Ross McDonald, while Patricia married a jockey.

By the time the gangly, disproportionate and thin-skinned chestnut colt wandered off a float and into their yard in the summer of 1977, the Hoysteds of Mordialloc were well-entrenched in the neighbourhood. Horses regularly came and went from the property—it was all part of the business of training. The fast ones tended to stay much longer than the slower ones, for the slower ones cost just as much to feed.

Bon Hoysted shook his head at the sight of the Manihi colt and headed inside the house. He had some phone calls to make.

The first was to the agent he’d trusted to purchase the yearling, Ed McKeon. Bon expressed his opinion of the unshapely horse, which made McKeon chuckle.

‘Bon, the instructions were to purchase him as long as there was nothing wrong with him, and I can assure you there isn’t,’ McKeon said. He added that beneath the appearance was a youngster with a massive lung capacity, as measured by the size of his girth, and a colt that should be ready for the early two-year-old races just several months away.

Then they had to settle the question of ownership. McKeon had paid for the purchase in Adelaide on behalf of Bon, but neither was interested in keeping the horse. The obvious person to ask was the client who owned Tumerah, the colt’s speedy but unruly older half-sister.

John Malcolm (Mal) Seccull was no stranger to owning horses—some of them faster than others. Tumerah had offered some excitement in a sport he deeply loved. Born during the Depression years, Seccull’s major pastime was horse racing, and he’d converted this interest into a long-term membership of the Victorian Amateur Turf Club (VATC), which conducted the race meetings at Caulfield and Sandown. (He would later become a life member, a committee member and vice president.) Seccull had continued his father’s successful construction business, JR & E Seccull (which was involved in the development of Melbourne landmarks such as Treasury Place and Westgarth Theatre), through the late 1950s, 60s and 70s. By the mid-1970s, Seccull began to scale back the construction business, moving into smaller developments and property management. His racing hobby became more of a focus and financing it was well within his means.

Now this hobby was beginning to pay for itself. Tumerah had only had a brief racetrack career but she’d been a winner, and Salyut—who had won more than twenty races—was another successful horse to come from the Hoysted-Seccull partnership. Additionally, Seccull had shared ownership of Tavel, a more-than-handy stayer trained by Bart Cummings.

Seccull preferred not to own too many horses at any one time, and with Tumerah and Salyut both in the Hoysted stables when the Manihi colt arrived, it wasn’t the easy sell that some had assumed. Initially, Seccull was reluctant—the hobby budget would need to be stretched back into the red if this purchase proceeded. Hoysted needed to persuade Seccull with reminders of Tumerah’s promise and Ed McKeon’s impressions from the recent sales.

For Seccull, the timing was lousy as he felt he had enough horses already. One solution to help de-risk the situation was to bring in a partner to go halves. This was entertained, calls were made but the responses were unfavourable.

While the matter of ownership was being resolved, the colt was broken-in by Ross McDonald, with time divided between the Mordialloc stables and another property a little further south-east of Melbourne. Throughout this form of pre-training the colt excelled, accepting the handling and gear, having somebody sit on his back, some barrier education, as well as some short bursts of running. His behaviour did waver occasionally into that of a cheeky juvenile, as he attempted to bully other horses. He may have been young, but he already understood that he was bigger and more powerful than the others.

McDonald felt he was a natural and a gifted runner. Not many eased through a horse-breaker’s hands in such a manner. McDonald was quick to report that the colt had all the attributes of his sister. Plus, he seemed to have the body to absorb and harness the power—a quality Tumerah lacked, hence why she was prone to injury.

Now well into his fifties, Bon Hoysted had heard great things from horse-breakers before. For various reasons, such glowing reports don’t automatically equate to glorious racetrack success. Nevertheless, it was the news he was hoping for and McDonald was a trusted and vital part of the training operation. McDonald’s high praise was taken at face value. The Manihi colt was being earmarked for the early two-year-old races, which were only a few short months away. There was no time to waste.

It was almost mid-year before the question of ownership was finally settled. After various co-ownership schemes fell through, Seccull decided to take on sole ownership. The glowing pre-training report and Hoysted’s promise that the horse would be at the races sooner rather than later, ultimately convinced Seccull to part with more of his hard-earned cash.

The young horse was immediately sent up to Yarra Park, Seccull’s 650-acre property at Gruyere, right at the foothills of the Yarra Ranges to Melbourne’s north-east. There the colt was promptly gelded. He had already become so big, heavy and strong that the decision was an easy one to make. A choice to leave him ‘as-is’ would have most likely led to an overgrown beast full of hormones, and therefore much more difficult to handle.

The gelding procedure was followed by a short break on Seccull’s farm before the horse returned to training. It was time to find out just how fast he could run.