Читать книгу Manikato - Adam Crettenden - Страница 6

Оглавление2

The Hardworking Kiwi

Gary Willetts was annoyed. This was unusual for the easy-going New Zealander, who had recently moved across the Tasman to further his exceptional career as a jockey. Willetts was beaten on a horse at Moonee Valley—one that was prepared by George Hanlon, a horseman Willetts rode for in both races and trackwork. The trainer was known to blame jockeys in defeat and he certainly let Willetts know about this one. Upon exiting the racecourse later, the humble Kiwi decided henceforth to exclude Hanlon from his trackwork rounds at Epsom.

The following Monday, Willetts steered his vehicle into a different driveway at Epsom. Instead of heading in the direction of horses trained by George Hanlon, he made for the lot prepared by Bon Hoysted. Good jockeys were in high demand at trackwork because of their experience. They assisted and collaborated with trainers on where to aim their horses for upcoming races. Hoysted duly greeted Willetts with a grin and several horses to ride.

* * *

Born in New Zealand in 1943, Gary Willetts devoted his childhood to further his dream of riding horses. At thirteen, he started working for trainer Fred Smith during school holidays. Not long after, he began an apprenticeship for the same trainer and had his first race ride in 1959. For the next fifteen years, he consistently kept himself in the top five on the national jockeys’ premiership in his homeland. He made the occasional trip to Australia to ride and had success with top-class stayer Battle Heights in the 1974 Cox Plate, Sydney Cup and Queen Elizabeth Stakes.

It was the week of the Queen Elizabeth Stakes victory that Willetts was first introduced to Bob Hoysted, brother of Bon and a successful trainer in his own right. Bob had a two-year-old—Scamanda—entered for the Champagne Stakes, and asked Willetts to ride him. After accepting the mount, Scamanda was ultimately scratched from the race, but Bob promised that one day he would make it up to the Kiwi if he ever returned to Melbourne. A seed had been planted.

Eighteen months later, the Melbourne spring of 1975 was a career highlight for Willetts. It all started with a lucky pick-up ride minutes before the Moonee Valley Cup for Bart Cummings on Holiday Waggon. Willetts made the most of the opportunity in the quagmire that afternoon. The following week, he piloted How Now to victory in the Wakeful Stakes at double-figure odds for Colin Hayes. On Oaks Day, Bob Hoysted stayed true to his word and engaged Gary Willetts to ride Scamanda in the Linlithgow Stakes. The pair crossed the line first. That spring was so successful, Willetts packed up from his Matamata base and moved to Melbourne permanently.

Willetts was a hard-working freelancer. When Epsom opened its gates at 3.30am for trackwork, he had his helmet and jodphurs on and was ready to ride his first horse of the morning. In an era where jockeys managed themselves, this was the most effective way of guaranteeing rides. Loyalty came from riding work.

Before then, Bon Hoysted had occasionally used Willetts at the races, but their newly laid trackwork arrangement had lasted all of one week before an unnamed yearling appeared from Mal Seccull’s Gruyere property and their relationship grew. The yearling hadn’t been away for too long, so changes to his bulging physique were minor. He was already nudging 550 kilograms—a hundred kilograms above the average weight for a horse his age.

On a chilly and dark Monday morning in late July 1977, the Manihi gelding got his first taste of the Epsom Training Track, a facility that held race fixtures until 1936 and was now used by over forty licensed trainers to prime their thoroughbreds for action. Bon Hoysted had one of the larger stables in the area.

Willetts was legged aboard the massive yearling and something stood out to him before they even took a step.

‘He had this huge head that looked all out of proportion with the rest of his body.’

The jockey didn’t know what to expect and as they walked to the track, Bon reminded him that he had only recently been broken-in. Willetts lengthened his stirrups for a little more balance and control before getting a feel for the chestnut. The morning exercise was to be no more than a basic induction to the surrounds of the training centre, which had several different tracks. There was an outside sand track, the course proper (with a circumference of around 1800 metres), another sand track (which would later become woodfibre), the ‘B’ grass, an inside sand track and the most inner track (which was a 1300-metre hurdle track).

Horse and rider trotted around the outside sand track for a few minutes before gently cantering off and then just running along a little quicker over the last 200 metres. With dawn still over an hour away, there was little to determine from sight. For Willetts it was all feel, and in that feel was an immediate liking.

‘I did have an ability to tell if a horse was any good from trackwork riding. It stood out to me instantly that he was a beautiful mover, despite having an awkward looking frame,’ says Willetts.

The real test of whether a significant engine roared inside the overgrown body was still to come, but the early signs were most encouraging.

* * *

Bon Hoysted started to plan the weeks leading to the first two-year-old races of the spring. While he wasn’t yet certain of the level of talent, he knew the young horse had already met many of the general criteria of an early-season juvenile. The youngster had been gelded and broken-in, was settling into stable life, had a mighty frame and was athletic. He was anything but scrawny and immature. On looks alone, he’d be able to psyche out many of his rivals.

It was plausible to aim high to start with; weaker races could be considered if he didn’t measure up to expectations. Most of the feature Melbourne race days had a two-year-old race programmed. The first was the Maribyrnong Trial, an $8000 race in early October at Flemington. Caulfield had the Debutant Stakes on Caulfield Guineas day the following week (worth $15,000), and the Merson Cooper Stakes the Saturday after (worth $20,000). Moonee Valley offered the St Albans Stakes on Cox Plate Day ($10,000) before the four days of the carnival at Flemington. The Maribyrnong Plate on Derby Day ($15,000) was a logical option too.

The timing of Hoysted’s training program dictated which race he was most likely to attempt. It took a number of weeks to properly educate an unraced horse and have him fit enough to compete. Most who were headed towards the Maribyrnong Trial already had several weeks’ preparation under their belts before the chestnut so much as got his first look at a training track. Time was already against Hoysted if he wanted to contest the opening two-year-events.

As the weeks progressed, a tilt at the St Albans Stakes or the Maribyrnong Plate seemed the more sensible and timely options to aim for. Having a winner on Cox Plate Day or Victoria Derby Day came with much prestige. A victory in either usually signalled that a trainer had a Blue Diamond Stakes or Golden Slipper Stakes calibre of runner.

However, plenty of time still had to pass, so much could go wrong. An injury would put a stop to the campaign, including shin soreness—a common ailment in younger horses. It was also possible that the horse couldn’t carry his huge frame fast enough to run in these events. They were all sprint races, run at a helter-skelter tempo. His family history suggested he could, but the proof was not yet in the pudding.

In order for the horse to race, he needed an official name. It was necessary for the Victoria Racing Club (VRC), racing’s governing body, to approve a name for each horse before accepting future race nominations. This was left entirely to owner Mal Seccull.

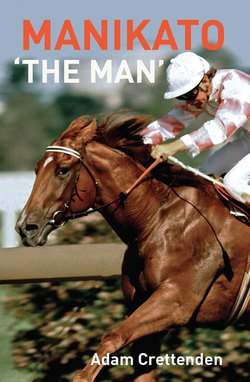

Most of Seccull’s horses had one-word names and this chestnut colt would be no different. It didn’t take long to invent a name that seemed to roll off the tongue—a blend word that took part of the name of his sire, Manihi, as well as part of the name of his dam, Markato. The submitted and accepted name was Manikato.

* * *

As the calendar moved to the spring equinox, daylight came earlier and the frigid, wintery mornings became brighter and milder. Manikato was starting to breeze-up comfortably in his work, reeling off speedy times without exhausting himself. Training was ticking over nicely, and a late October debut run remained a distinct possibility. With dawn much earlier, Bon Hoysted could now see for himself how his newcomer was tracking and what type of action he had.

Like many raw juveniles, he had some tendencies to make a rider slightly nervous. He was a little edgy once saddled in a stall adjacent to the track, and just as he was about to step onto the track he’d take a moment and stand still. He’d move on only when he was ready.

Because of their tendency to hesitate and not concentrate when they are running alone, most two-year-olds are ‘buddied’ to keep them company when doing their track gallops. It’s ideal to measure up two horses of similar ability so they can round out their work alongside one another. It was a good sign that Manikato was finishing off his trackwork under a strong hold while his companion was flat-out trying to level up. Hoysted started sending a three-year-old out with Manikato.The result was the same.

It soon became apparent that Hoysted’s leading two-year-old was Seccull’s Manihi gelding—‘Kato’ as he had been dubbed by stable staff, it seemed Hoysted was vindicated in aiming for a high-class city race for the horse’s debut run. In pondering which race to target, it was now down to either the St Albans Stakes at Moonee Valley or the Maribyrnong Plate at Flemington to kick off Manikato’s career—two vastly different racecourses. Manikato would need to manoeuvre around a tight turn and a short home straight at Moonee Valley, while the Flemington race was down the famous straight course. Both venues had their traps and Hoysted wanted to remove as much of the risk as possible before the debut run. There was money to be made, not only from the lucrative prize money, but from the prospect that bookmakers may offer good odds and allow a decent bet. It remained the dream of many to set up a horse for a ‘sting’ and walk away rich.

The more Hoysted thought about it, the more he worried about the circuit at Moonee Valley. His unraced youngster was large and may not appreciate the smaller track. The Flemington race also allowed an extra week to prepare and ensure Manikato’s fitness was spot-on. Hoysted resolved to declare the Maribyrnong Plate as the target. There was just one important piece of work left to do.

Five days out from the race, Hoysted loaded Manikato on to a float and trekked across Melbourne. Having been nominated for the following Saturday, the horse was allowed a look at the straight course at Flemington. It was the final tune-up for the Derby Day race meeting. Many weeks of build-up were almost complete.

Manikato was walked and then saddled. Gary Willetts was legged aboard and the pair were sent out onto the grass where they headed towards the top of the straight.

They turned near the 1000-metre post to canter off, with the instructions to gradually build-up until they met with the course proper (with around 400 metres to run) and then zip home. It was a solo gallop—no companionship for the gelding this day. Willetts held all the experience, Manikato none.

The jockey guided the two-year-old on the hit-out and the first 200 metres went well. The stride was straight and just beginning to lengthen. But just inside the 800 metres, Manikato spotted a line across the track. It hadn’t worried him at just a trot heading up the track a few moments earlier, but now his ears laid back and Willetts could sense it was bothering him. It was a crossing—one of several at various points around the Flemington course—and it was intended to allow vehicles to pass. Its colour was distinct from that of the turf.

Willetts was prepared. It wasn’t the first time he had encountered this issue in riding the track. Indeed, some horses were known to baulk in the middle of a race. He braced for the seconds ahead.

‘He started to shy and I didn’t know if he was going to stop, go sideways or jump. Ultimately, he virtually did all three. He propped and jumped sideways and it felt very awkward,’ recalls Willetts.

The track gallop was completed and, while nothing seemed horribly awry that day, the following morning Kato was tender to touch across the back. It was clear that the crossing incident at Flemington had caused an injury. It was enough to scratch from the engagement on Derby Day. One rueful misstep and a whole preparation was flushed away. But that’s racing, as a pragmatic Bon Hoysted reminded himself. A diagnosed muscle strain meant a couple of weeks of rest before the horse could be tried again. The spring riches and the planned betting plunge turned out to be the stuff of fantasy, at least in the very short term.