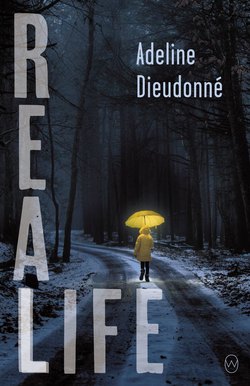

Читать книгу Real Life - Adeline Dieudonné - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

IF YOU CROSSED Little Gallows Wood then went through the field without being seen by the farmer, you got to the big slope of yellow sand. And if you went down it, hanging onto plant roots, you entered the labyrinth of broken cars. There, too, you had to make sure you weren’t seen.

It was a vast metal boneyard, and I really liked the place. As I stroked the cars’ shells, I would imagine them as a heap of creatures, motionless yet sentient. Sometimes I talked to them, especially the new ones. I told myself they must need reassuring. Sam would help me. The pair of us could spend whole afternoons talking to the cars. Some had been there a long time, so we got to know them well. There were those that were virtually unmarked, and others that were slightly damaged. And then there were those that were totally wrecked, hood ripped open, body shredded, as if chewed up by some huge dog.

My favorite was the green car devoid of both its roof and its seats. It looked as though it had been scraped clean at hood level, like foam on a glass of beer. I wondered what could have sliced it like that. Sam liked the “Boom-a-roller,” as he called it. We would imagine that this funny old Boom-a-roller had been put into a giant washing machine, but without water. It was dented all over. Sam and I would get inside and pretend we were in the washing machine along with the car. I would take the wheel and cry “Boom-a-roller! Boom-a-roller! Boom-a-roller!” while bouncing up and down on the seat to make the car shake. And Sam’s magic laughter would climb all the way to the top of the slope of yellow sand. At which point we knew we had to skedaddle because if the owner heard us, it wouldn’t be long before he turned up. The labyrinth was his domain and he didn’t like anyone coming to play there. The older kids in the Demo had told us he set wolf traps to catch children playing close to his cars. So we always looked carefully where we put our feet.

Whenever the owner heard us, he would arrive yelling “What’s all this?” and we would have to scram before we got caught, climbing back up the slope, hanging onto the roots, fighting the fear that made breathing difficult, and run a long, long way from the shouts of “What’s all this?” Being fat and heavy, the guy couldn’t climb very far up the wall of sand.

One day, Sam grabbed hold of a too-slender root, and it broke. He fell straight down, landing a few inches from the huge hands that were trying to catch him. He leapt like a cat, I caught him by his sleeve, and we barely made it out of there. Once up top, we laughed in fright. We went to see Monica beneath the ivy to tell her about it. She laughed too, but warned us not to have any hassle with him. She said it just like that, in her voice that sounded like an old car horn, and with her beachy scent: “You know, kiddies, there are people you shouldn’t approach. You’ll learn that. There are people who’ll darken your skies, who’ll steal your joy, who’ll sit on your shoulders to stop you flying free. He is one such person. Stay well away from people like that.” I giggled, imagining the owner of the wrecking yard sitting on Sam’s shoulders. Then we left for the Demo because we heard the music—Tchaikovsky’s “Flower Waltz”—coming from the ice-cream man’s truck, bang on time, as he was every evening. We went to ask our father for some money.

Sam always had two scoops, vanilla and strawberry. I chose chocolate and stracciatella, with whipped cream, even though whipped cream was forbidden: my father didn’t approve, I don’t know why. So I quickly gulped it down before we went home. It was a secret I shared with my little brother and the nice man in the truck. He was very old; he was bald, tall, and slender; and he wore a brown velvet suit. He would always tell us, in his gravelly voice and with a gleam in his eyes, “Eat it fast before it melts, kiddos, because it’s sunny and windy, and there’s nothing worse for ice cream.”