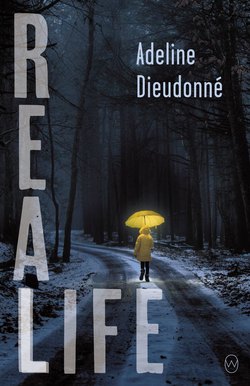

Читать книгу Real Life - Adeline Dieudonné - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

OUR HOUSE HAD four bedrooms. There was mine, my little brother Sam’s room, that of my parents, and the one with the carcasses.

Deer calves, wild boar, stags. And antelope heads, of all sorts and sizes, including springboks, impalas, gnus, oryxes, and kobus. A few zebras minus their bodies. On a platform stood a complete lion, its fangs clamped around the neck of a small gazelle.

And in a corner was the hyena.

Stuffed she may have been, yet she was alive, I was sure of it, and she delighted in the terror she provoked in any gaze that met her own.

In the framed photographs on the wall, my father posed proudly with various dead animals, holding his rifle. He always took the same stance: one foot on the beast, fist on hip, the other hand victoriously brandishing the weapon. All of which made him appear more like a rebel fighter high on genocidal adrenaline than a father.

The centerpiece of his collection, his pride and joy, was an elephant tusk. I had heard him tell my mother one evening that the hardest part wasn’t killing the elephant. No. Killing the beast was as easy as slaughtering a cow in a subway corridor. The real difficulty had been making contact with the poachers and avoiding the patrolling game wardens. And then removing the tusks from the still-warm body: utter carnage. It had all cost him a small fortune. I suppose that’s why he was so proud of his trophy. Killing the elephant was so expensive he’d had to split the cost with another guy. They left with a tusk each.

I liked to stroke the ivory. It was silky smooth and large. But I had to do it behind my father’s back. We were forbidden from entering the carcass room.

* * *

My father was huge with broad shoulders, the build of a slaughterman. He had a giant’s hands. Hands that could have ripped the head off a chick the way you’d pop the cap on a Coke bottle. Besides hunting, my father had two passions in life: television and Scotch whisky. When he wasn’t scouring the planet for animals to kill, he plugged the TV into speakers that had cost as much as a small car, a bottle of Glenfiddich in his hand. And the way he talked at my mother, you could have replaced her with a houseplant and he wouldn’t have known the difference.

My mother lived in dread of my father.

I think that’s pretty much all I can say about her, leaving aside her obsession with gardening and miniature goats. She was a thin woman, with long limp hair. I don’t know if she existed before meeting him. I imagine she did. She must have resembled a primitive life form—single-celled, vaguely translucent. An amoeba. Just ectoplasm, endoplasm, a nucleus, and a digestive vacuole. Years of contact with my father had gradually filled this scrap of nothing with fear.

Their wedding photos always intrigued me. As far back as I can remember, I can see myself studying the album in search of a clue. Something that might have explained this weird union. Love, admiration, esteem, joy, a smile … something. I never found it. In the pictures, my father posed as in his hunting photographs, but without the pride. An amoeba doesn’t make a very impressive trophy, that’s for sure. It isn’t hard to catch one: a bit of stagnant water in a glass, and presto!

When my mother got married, she wasn’t frightened yet. It seemed as though someone had just stuck her there, next to this guy, like a vase. As I grew older, I also wondered how this pair had conceived two children: my brother and me. Though I very soon stopped asking myself because the only image that came to mind was a late-night assault on the kitchen table, reeking of whisky. A few rapid, brutal, not exactly consenting jolts, and that was that.

In the main, my mother’s function was to prepare the meals, which she did like an amoeba might, with neither creativity nor taste, but lots of mayonnaise. Ham and cheese melts, peaches stuffed with tuna, deviled eggs, and breaded fish with instant mashed potatoes. Mainly.