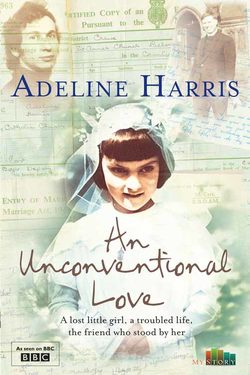

Читать книгу An Unconventional Love - Adeline Harris - Страница 11

Chapter Six Oaklands, Crewe

ОглавлениеOaklands was a big two-storey house in a district to the west of Crewe called Woolstanwood. As soon as Dad unlocked the front door, Harold and I dashed inside to explore the maze of empty rooms with bare wooden floors and to scramble up the creaking staircases with a clatter of feet. We were exhilarated at the sheer amount of space after months in a poky room in a boarding house, and we ran round and round burning off energy after the long taxi ride. There were seven bedrooms and several reception rooms, and outside there was an acre of garden with four lawns, an orchard and a vegetable patch.

‘Can I have the big bedroom at the back?’ I begged Dad.

‘But I want that one,’ Harold whined, in his babyish three-year-old’s voice.

‘You’ll both be sharing the little front bedroom,’ Dad told us.

‘Why can’t I have my own room? There’s loads of space.’

‘There won’t be space for long,’ he said, and he explained that eight of our relatives were arriving soon from India: Aunt Muriel, Mother’s sister, with her husband Charles and teenage daughter Margaret; my grandparents on Mother’s side; my grandfather’s two sisters, and the grown-up daughter of one of them. How would we all fit?

‘We must be kind and welcoming,’ Mother told me. ‘They’ve had to leave their homes to come here because it wasn’t safe in India. They’ll be homesick and sad, just as we were when we arrived.’

Harold’s and my room was so small that there was only just space for two twin beds side by side and nothing else. I wasn’t happy about this, as I found my brother intensely annoying and preferred to keep as far away from him as I could. There was a cupboard outside on the landing where we were told we could keep our toys, but we hardly had any. We didn’t have many clothes either. It was part of the strict ethos our parents lived by: ‘You only need one shirt on your back,’ Mother would say, ‘and you can only read one book at a time.’ They were very, very religious.

A flurry of builders and decorators arrived, bringing the sounds of banging and crashing and the smells of paint and new carpet and wallpaper paste. Mother sat at the top of the stairs and cried in the midst of the chaos, but I loved to watch the men at work and asked them endless questions about what they were doing, and why.

‘We’re building a partition, to make this into two rooms,’ they told me. ‘This is where the door will go.’

Dad’s new job was as Group Engineer and Building Supervisor for the South Cheshire Hospitals Management Committee and he managed to get the contractors working on the hospitals to come and do building work for us. By the time the relatives arrived, they not only had their own bedrooms, but private sitting rooms downstairs as well, all smartly decorated and carpeted and furnished with reproduction antiques from a furniture showroom. Dad bought a big oak refectory table with twelve leather studded chairs so we could sit down to have dinner together in the evening. The polo trophies appeared, along with the silver hors d’oeuvre trays and knives and forks all engraved with the Harris family crest. And the crucifix that had saved Dad’s life in the Family Miracle was given its own place in the hall, surrounded by candles, just as it had been in Beesakope.

When I looked at that precious crucifix, a thought came into my head: ‘We’re not going back.’ Up till then it had been a holiday in London, and a holiday in Felixstowe, but now it seemed as though this was real life. We were going to stay here. I gave a little scream and ran upstairs to bed in tears. Dad came up after me.

‘We’re not going back to India, are we?’ I sobbed.

‘Not quite yet,’ he said. ‘Your Grandfather Harris is very old and he might not live much longer. Don’t you want to see him while you still can?’

‘I want to see Clara,’ I wailed.

‘She’ll still be there. She’s a young woman. You’ll see her again.’

He did his best to make me see the bright side of our new home – such a lovely house, and England was the best country in the world – but I was distraught, and I know Mother was the same. I overheard them talking at night when we were supposed to be in bed and always Mother would say, ‘I told you I would not live in England. I told you I wanted to bring up my children in India.’ Dad used the same patient tone he used with me, trying to win her over, but it was a lost cause.

Mother had never done a stroke of housework in her life, so servants had to be hired: a cleaner and cook called Mrs Barber, a nanny for Harold and me, and a gardener to tend the grounds. Mrs Barber had been a cleaner at one of the hospitals Dad supervised but she’d lost her job and Dad felt sorry for her so he invited her to work for us. She didn’t live in but she came six mornings a week to clean and polish and dust the silver trophies and then she’d pop back in the evening to heat up meat pies and boil potatoes for our dinner. She wasn’t a great cook, but she was infinitely better than Mother. On Mrs Barbour’s day off, Mother would cut tinned corned beef into chunks and heat them up in a tin of vegetable soup, announcing ‘It’s dog’s dinner today.’ It looked for all the world as though someone had thrown up on the plate, and tasted pretty disgusting as well.

Mother never got the hang of shopping for food. Rationing was still in force in postwar Britain and you had to take coupons to the shops to claim your allowance, but she just couldn’t understand that. She’d turn up at the butcher’s and ask for some lamb chops but he wouldn’t give them to her because she didn’t have the right kind of coupon. She was a real fish out of water.

Appearances were important to Mother. She’d buy the cheapest kind of jam and put it in a silver jam pot with a little silver spoon. Dad was always complaining: ‘This jam hasn’t seen a raspberry, the seeds look like pieces of wood and it tastes as though there’s sawdust in it.’ She bought cheap whisky and sherry as well, and poured it into cut-crystal decanters.

Mother wasn’t good at shopping for food and she didn’t wash clothes either. We wore our clothes over and over again until they were so filthy and smelly that they had to be thrown out. Every week she bundled up the larger items, such as sheets and pillowcases, towels and Dad’s shirts, for the Sunlight Laundry van to take away and wash, but she never washed our underwear or pyjamas or shirts or jumpers. To make matters worse, we weren’t big on bathing as a family. If I got my knees muddy in the garden, she’d make me brush the dirt off before I got into bed but I only climbed into the bath for an all-over wash every few weeks, when Dad told me I had to. Personal hygiene wasn’t something that concerned Mother.

Soon after we arrived at Oaklands in September 1949, I was enrolled at St Mary’s Roman Catholic Mixed School in Crewe, which was the roughest, poorest school in the area, with a big intake of Irish immigrants and local kids whose fathers worked in the car factory or on the railways. I was a skinny little girl with poker-straight dark hair, which was cut in a short bob with a fringe above my eyebrows, while all the other girls seemed to have pretty curly hair. My clothes looked different as well. Mother bought me a woolly muff to keep my hands warm, while all the other kids had gloves. They had hats but I looked terrible in a hat because of my fringe. My skin was darker than theirs, I had different clothes and I spoke with a funny foreign accent so, as Dad had predicted, I was picked on right from the start.

I didn’t hold back. In response to any teasing, no matter how harmless, I let loose with one of the big punches Dad had taught me while we were on board ship. If someone held their nose as I passed, they’d get thumped. If I overheard someone calling me ‘Red Indibum’ behind my back, I’d turn and swing at them. I punched and I punched and there were black eyes and split lips all round, but nothing stopped me.

Many a mother came in to complain to the teachers: ‘Adeline Harris has broken my son’s front tooth.’

I was constantly called up to the headmaster’s office and instructed to hold out my hand. He would raise a cane into the air and bring it down on my outstretched palm and, while it smarted and stung at the time, I didn’t think it was too bad as punishments go. It certainly didn’t deter me from fighting. I went straight back out to the playground and I punched and I punched some more. No one got the better of me in a fight, not even the boys.

Letters were sent home, and Mother wept to think that a daughter of hers should be reprimanded for fighting, but Dad was secretly proud of me. He whispered: ‘Keep the stiff upper lip and punch them hard.’

‘She just needs to get settled,’ he said to Mother. ‘The move has been a big upheaval for her.’

‘I told you we’d have trouble with her. I said so on the boat from India.’

There was only one good thing about that school as far as I could see and that was the school dinners. For the first time, I learned to love English food. There were tasty cottage pies and fish pies and stews served over mashed potato. The very first day there, I got into trouble for picking up my plate and licking it to get the last drop of gravy.

More firsts came and went: first mass in our new church, first reading lessons, and then along came my first English Christmas. If Mother and Dad had anything to do with it, it was going to be an austere, primarily religious festival, with mass every day and maybe a couple of cheap gifts such as a new pair of socks and a book (preferably religious). However, a few days before Christmas a remarkable thing happened.

School had finished for the holidays and I was sitting looking out of the window when a big black shiny car pulled up outside our gate.

‘That’s a Rolls Royce,’ my cousin Margaret said. ‘Who can it be?’

A chubby man with a round face and hair combed into a centre parting walked up the path and knocked on the door. Mother came rushing through the hall to answer it then shrieked out loud. Dad was in the drawing room decorating the Christmas tree. As he came out to the hall to see what was going on, I crept onto the landing to spy on them. I wasn’t close enough to hear all that was said, but I gathered that the man was an old friend of Mother’s from before she was married and that Dad didn’t seem too pleased to see him. He wasn’t invited in.

They chatted for a while, then the man said, ‘I’ve got some Christmas presents for your children. They’re in the car.’ As he headed out towards the Rolls Royce, I scurried downstairs and out into the front garden so I could watch as the chauffeur opened the boot. My eyes widened like saucers as he pulled out two huge packages wrapped in brown paper.

Mother turned to me. ‘What do you say to the kind gentleman?’ she asked, her tone neutral.

‘Thank you very much, sir,’ I said with feeling.

Dad seemed keen to get rid of him though. ‘So at last we meet,’ he said in a crisp voice, and folded his arms.

The man took the hint. Goodbyes were said, the car pulled away and I clamoured for answers. ‘Who is he? How do you know him? Can we keep the presents? Please say we can!’

‘Let’s see what they are first,’ Dad said. He tore off the paper to reveal a bright blue pedal car with a Rolls Royce badge on it, presumably for Harold, and a Silver Cross pram for me. I had a doll who would fit into it perfectly and wanted to start playing with it straight away.

‘We’ll put them under the tree till Christmas Day,’ Dad announced, and Mother said nothing. I was disappointed not to be able to play with the pram straight away, but at least I got to keep it.

For the next couple of days I sat looking at the amazing sight of the tree covered in flickering candles, with our lovely presents waiting underneath, like an unimaginable wonderland. It was only later Mother told me that the man who’d brought the presents was the cotton factory owner from Lancashire to whom she had been engaged for seven years before she met Dad. He heard she had moved to England and came to see her. She laughed as she explained that he wanted to win her back, even though she was married with two children. ‘Poor man!’ she sighed, shaking her head. Anyway, Harold and I got our best Christmas presents ever as a result, so we weren’t complaining.

January was a grim month of sleet and freezing rain and grey, overcast skies. My grandparents had had enough. They didn’t like the climate, didn’t like the food, didn’t want to stay here, so after three months of an English winter they upped and flew back to Bombay.

‘The atmosphere is too damp, Emily. I can’t breathe here,’ her mother said.

They couldn’t return to their house because it still wasn’t safe, so they gave all their possessions to a convent in Bangalore, in return for which the nuns agreed to take them in and look after them for the rest of their lives.

‘Can’t I go too?’ I begged. ‘I could train to be a nun there.’ In my head, I thought Clara could come over and live with me and we would be nuns together. Not a day passed without me missing Clara.

Dad gave me short shrift. ‘Your school is here. Your parents and your brother are here, and this is where you are going to live. Please try to understand.’

I didn’t like my school though. If I couldn’t go to Bangalore, I wanted to go to the Ursuline convent in Chester, which had a lovely green and grey uniform, but for some reason Dad wouldn’t let me.

‘Let’s see if you pass the Eleven Plus,’ he said. ‘You can go to a different school after that. Be good, sweet maid, and let who can be clever.’

Eleven sounded ages away when I was only just seven. ‘But I want to be a nun,’ I insisted. ‘I should go to school in a convent so I can learn how they work.’

‘You can become a nun after you’ve finished St Mary’s,’ he said. ‘There’s plenty of time for that.’

I still felt like the outsider at that school. My family did things differently from all the other families. As a case in point, the rest of the class went swimming every Tuesday in the Crewe swimming baths but Mother didn’t want me to swim there. First of all, I would have to show my arms and legs to everyone else, which wouldn’t be modest and proper. Secondly, I might catch something horrible from the water, or be exposed to some awful disease in the changing rooms.

I was embarrassed to be the only one in the class who wasn’t allowed to swim, so I took my old ruched swimsuit from the summer and an ancient threadbare towel and I put them in a plastic bag, which I dropped out of my bedroom window into the flowerbed outside. On the way to school on Tuesday morning, I picked up that carrier bag and was able to go swimming with my classmates. After school I hid the bag full of wet things in some bushes in the garden. The following Tuesday morning I picked it up again and the costume and towel were all damp and mouldy and smelled so dreadful that no one would stand beside me, but at least I could go swimming with the others. I did this each week, the smell getting worse until the costume and the towel disintegrated.