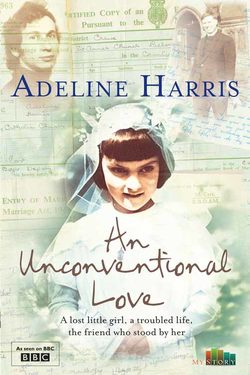

Читать книгу An Unconventional Love - Adeline Harris - Страница 9

Chapter Four Earl’s Court Hotel, London

ОглавлениеWe disembarked into grim, cold, postwar Britain and our bags were loaded into a taxi Dad had booked for us. The trunks were going to follow on later. Mother was still sobbing and Harold and I were sniffling and Dad kept apologising: ‘I’m so sorry. It will all be fine. You’ll see.’

We drove out of the dockyard into the town of Tilbury and I peered through the window at streets lined with rows of houses that all looked the same as each other, and shops with the goods stuck away behind big glass windows instead of out on display on the street. There were more cars and trucks and vans than I’d ever seen in my life, and our taxi had to sit in queues, making me feel hemmed in. I was homesick for the sea of green fields stretching as far as the sky outside our house in Beesakope. I was homesick for the colours of the goods in the bazaar, and for the sad-eyed elephants, and most of all I was homesick for Clara.

‘Why couldn’t Clara come with us?’ I asked for the umpteenth time.

‘Her children are in India. She doesn’t belong here,’ Dad told me.

‘Neither do I,’ I thought, ‘so that’s not a good reason.’

It was a long way from Tilbury to the White House Hotel in London’s Earl’s Court, where Dad had booked us in. Harold was sobbing to himself so I put my arm round him and gave him a cuddle. When Dad said we had arrived in London, I gazed out of the window hoping to see the King and his palace, but all I saw were more buildings, bigger ones now, and nose-to-tail cars everywhere I looked. People crowded the pavements but I couldn’t see their faces because they were holding umbrellas against the drizzle.

‘You’ll love London,’ Dad told Mother. ‘I know it from my student days. We’ll go and see shows in theatres, and explore the museums and galleries. It’s the most cultured city in the world.’

Mother wiped her eyes with a handkerchief and took out a handbag mirror to check her appearance. ‘There was plenty of culture in India,’ she said under her breath.

‘What’s culture?’ I asked, but everyone ignored me.

It was evening when we arrived at our hotel, and there was just time for a quick tea – more flavourless, colourless English food – before bed.

‘You won’t be needing the sleeping medicine any more now,’ Dad said gaily. ‘There’s nowhere you can fall overboard in a hotel!’

He and Mother went down for dinner, after locking us in the room, and I lay in bed hugging my pillow and sobbing for Clara. Harold was crying even harder than me, going red in the face and choking on his tears until eventually I crawled into his bed to comfort him.

Next morning, we ate breakfast with Mother and Dad in the hotel dining room and Mother frowned and tutted as I scooped up scrambled egg between my fingers, the way I always ate back home.

‘She needs a spoon and pusher,’ Dad said with a twinkle in his eye, but Mother didn’t think it was so funny.

‘Hasn’t Clara taught you how to use a knife and fork? You can’t eat like that here.’

I lifted my knife and fork but the egg was slippery and I couldn’t work out how to make it stay on my fork long enough to get it to my mouth. I had woken up with a pounding headache behind my eyes and I felt strange, as though I might be going down with a cold, but I didn’t mention it.

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake.’ Mother raised her eyebrows. ‘We’ll have to teach you table manners.’

‘Eating is an art,’ said Dad, and from then on our mealtimes became an extended lesson in etiquette. Other children might chat to their parents, crack jokes even, but for Harold and me meals were a training ground where we had to learn how to sit up straight, how to hold a knife and fork, peel an orange, take the pips out of grapes and cut a banana into pieces while keeping it in its skin. All this had to be done without causing offence to anyone else at the table.

‘Where are we going today?’ I asked that first morning.

‘Your mother and I are going out sightseeing but you children wouldn’t be interested, so we’ve arranged for a governess called Madame Bobé to look after you. I’m sure you’ll have much more fun with her.’

A governess? Wasn’t that like a teacher? I wasn’t sure I liked the sound of this and I pulled one of my faces, only to be told off by Mother.

Dad took us on the Underground to Madame Bobé’s apartment, and Harold cried all the way, scared of the noisy silver train rattling in and out of tunnels and the doors that slid closed with a clunk. I watched the people, jostling and pushing on the platform, or heads down, poring over their newspapers on the train. They didn’t look at us once. It was as if we were invisible. The noises of the train made my head hurt even more and I clutched my face in my hands.

Madame Bobé’s place was in a basement below ground level, and she ushered us into a room full of toys. I had never seen so many in my life before. There were dolls, and a train set and cars, and games and teddy bears – all kinds of wonderful things I had never come across, so initially that looked promising. The room smelled musty, of velvet hangings and the old eiderdowns she used to protect her good chairs from our little feet. There was a Wilton carpet with an intricate pattern that made you dizzy when looked at and one big window through which we could look up at the feet passing in the street above but couldn’t see people’s faces.

‘Is this where you live?’ I asked. ‘Don’t you feel funny being underground?’

Madame Bobé replied in French, which was a problem because Harold and I only spoke Hindi and a limited number of English words.

‘We’ve asked Madame Bobé to teach you French,’ Dad told us, glancing quickly around the room, before they hurried off to retrace his student days around the sights of the capital.

Madame Bobé settled herself in a chair in the corner, looking stern, as she let us get on with exploring the toys. She indicated that we were allowed to play with them one at a time while she focused on her needlepoint. She may have been called a governess but she made precious little attempt to teach us anything.

Before long, my brother wanted to go to the toilet and he used the word we had always used: ‘Number.’ We said ‘nina’ when we wanted a wee-wee and ‘number’ for a number two.

Madame Bobé thought he was saying ‘number’ in English and that he wanted her to teach us numbers so she began to count: ‘Un, deux, trois, quatre…’

‘No, number!’ he insisted urgently. ‘Number!’

And she began again: ‘Un, deux, trois, quatre…’

I tried to help by speaking very clearly: ‘Number.’

‘Un, deux, trois…’

Finally Harold started crying as the inevitable happened and he dirtied his pants. I think she realised then.

Mother and Dad picked us up at five o’clock and we had another Tube journey back to the hotel for high tea and a cutlery lesson, followed by the Rosary before bedtime. I wasn’t very impressed with my first day in London.

‘When can we go to see the King?’ I asked, and they both laughed and didn’t answer me.

Harold and I weren’t supposed to talk at mealtimes; we were supposed to eat our food in silence. I felt a bit sick so I just played with my tea and listened to Mother and Dad’s conversations about the places they had been that day. It was through this that my English began to improve until I could understand most things they said.

Harold and I never did get to see the sights ourselves. The only place we were taken was to the Brompton Oratory for mass on Sundays. I was impressed by the stained glass and the great big dome but would much rather have accompanied Mother and Dad on their sightseeing tours than be stuck indoors with Madame Bobé. She didn’t once take us out of her flat. We sat, day after day, bored out of our skulls while she fiddled away at her needlepoint.

My nagging headaches lasted for two or three weeks, and I frequently felt nauseous, but I thought it was because of the horrible, stodgy English food. There was also a kind of dizziness, a disorientation that I couldn’t put my finger on.

‘I don’t like England because it makes you have headaches all the time,’ I told Mother one day.

‘What kind of headaches?’

‘Sore ones. And I feel sick as well.’

Mother called out a doctor but he could find nothing wrong with me, and they put it down to homesickness and a bit of play-acting. It wasn’t, though. My symptoms were very real.

It was only many years later, while talking to a doctor, that I realised I went through morphine withdrawal at the age of six during that stay in London. Such a thing wasn’t even considered in those days, when morphine-based medicines were freely available over the counter in chemists’, but that’s what it must have been.