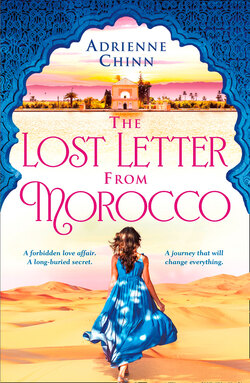

Читать книгу The Lost Letter from Morocco - Adrienne Chinn - Страница 12

Chapter Six

ОглавлениеZitoune, Morocco – November 1983

From his perch on an aspen branch, Omar watches the Irishman knock in the final tent peg with a rock. The man – Gus he’d said his name was – has chosen a good location. No one comes up here to the source of the waterfalls with the Roman bridge. No olive trees up here. And tourists never find the path. They only want to see the waterfalls then go back to Marrakech for their supper.

This Gus isn’t like the other tourists. Omar has spied on him at the weekly market, bargaining for mutton and vegetables in Arabic. Like the Arabic he’s learning in school, not like Darija. It’s probably why no one understands Gus well. Sometimes Gus tries to speak Arabic to the Amazigh traders from Oushane and the villages even further in the mountains, which is crazy. Everyone knows they speak only Tamazight.

Yesterday, Gus bought a small round clay brazier and a tagine pot from the market. Old Abdullah charged him too much: fifty dirhams. And the man paid! Omar will try this when he sells the ripe olives to the tourists. ‘Fresh olives from Morocco. Fifty dirhams!’ He’ll make a big profit. He’ll give his brother, Momo, and his friends, Driss and Yassine, olives to sell, as well. Pay them one dirham each. He’ll be a rich boy soon, especially since he steals the olives. Almost one hundred per cent profit. Maths is the only subject he likes at school. Maths and French, because he needs to talk to the tourists. He rubs the angry red welt on his arm. His grandmother was right to punish him with the hot bread poker for missing his classes. If he was to be rich one day, he couldn’t be lazy. One day he won’t have to sleep by the donkey, and he’ll build his mother a fine big house, better even than the house of the policeman. And they’ll all have new clothes from the shops in Azaghar, not the old clothes his mother brought back from helping the ladies with the babies in the mountains. One day for sure he’ll be a rich man.

Hunching over the brazier, Gus takes a silver lighter out of his shirt pocket and lights the coals he’s stacked inside. Too many. Jedda would punish Omar if he used so many coals.

Omar’s eyes follow a flash of silver from the man’s shirt pocket to his fingers. Gus flicks the silver lighter. A thin blue flame waves in the air. Gus leans over the brazier with the flame until a coal catches light. He flips back the lighter’s lid. Back into his pocket. Silver. Gus must be rich.

Gus throws a handful of sticks onto the coals and sets the grille on top of the brazier. He sits back onto a low wooden stool. A pan of water is on the ground by his feet. He reaches into a canvas rucksack and pulls out a potato. His other hand in his trouser pocket. A red pocket knife. The knife scraping against the potato skin. Shavings falling onto the earth. Fat chunks of white potato plopping into the water. Gus doesn’t know how to make tagine well.

Omar shimmies down the skinny aspen, its yellow autumn leaves falling around him like confetti.

‘Mister Gus! Stop!’

‘Looks like I’ve got a spy. Omar, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. Everybody knows me here.’

Omar lopes over to Gus, his Real Madrid football shirt loose on his slender body. His toes poke out from the torn canvas of his running shoes under the rolled-up cuffs of his jeans.

‘That’s not how you cut vegetables for tagine. They will never cook like that.’

‘A spy and a professional chef. You’re a very talented boy.’

Omar sticks out his hand. ‘Give me the knife.’

The corners of the man’s eyes crinkle as he smiles. He hands Omar the pocket knife.

‘So, Mister Boss. Show me how it’s done.’

Omar picks a potato out of the sack and squats next to the pot of water. After scraping off the skin, he cuts the potato into four long white slices.

‘Like this,’ he says. ‘Like fat fingers. Then the heat will cook them well.’

He pulls out a long carrot and rasps the blade against the skin, the dirty orange shreds spiralling onto the ground. He chops off the leafy top and the tip, then slices the carrot into two vertically. Then he scoops out the green core and cuts the carrot into thin strips.

‘Like that.’ He drops the slivers into the pot. ‘Very good.’

Gus holds out his palm. ‘Let me try.’

Omar hands back the knife. ‘Mashi mushkil.’

‘No problem. That bit of Darija I’ve learned.’

Omar rests his elbows on his thighs as he watches Gus scrape the skin off a carrot.

‘You sound different than the French tourists from Marrakech.’

‘I’m Irish, but I live in a very faraway place called Canada. A very beautiful place by the sea. But really I’m a nomad. I travel the world to search for oil in rocks. That’s why I’m here. There were a lot of dinosaurs in Morocco. Wherever there were dinosaurs, there’s usually oil.’

‘I know where there are some footprints of dinosaurs. Not so far from here.’

‘Really? Will you show me?’

Omar shrugs. ‘For fifty dirhams.’

‘Twenty dirhams.’

Omar’s eyebrows shoot up: twenty dirhams? He would’ve shown the man for free. He screws up his small angular face.

‘Thirty dirhams.’

Gus raises an eyebrow and holds out his right hand. ‘Highway robbery – thirty dirhams. Deal.’

Omar puts his small brown hand into the man’s large, square-fingered hand and they shake.

‘It might be that you will need a guide here, Mister Gus. I know all the good places to visit around Zitoune. I know a place of dinosaur feet and a cave with many old drawings. We can make a good negotiation.’

‘You’ll make me a poor man, for sure, Omar. What about if I teach you English so you can talk to any English tourists who visit the waterfalls, not just the French? You can corner the tourist market. No one here speaks English.’

Omar squints at the glowing coals as he mulls over the offer. Dirhams now would be good. But then once the man leaves, the money stops. But, if he learns English, even when Gus leaves, he can still earn money. Lots of money. Omar holds out his hand.

‘Deal.’